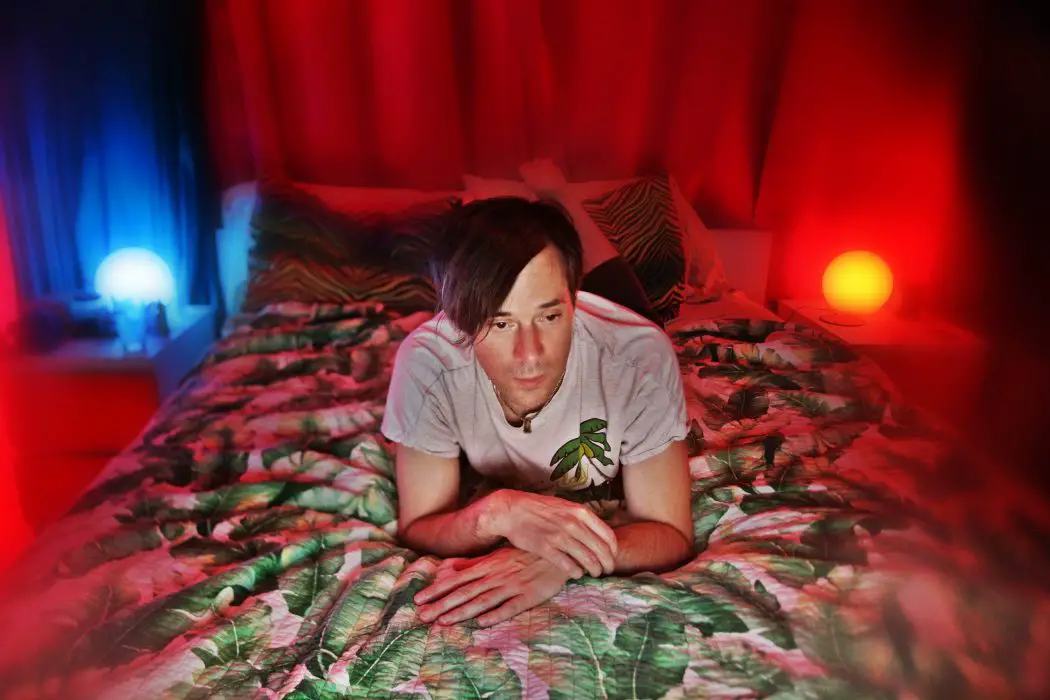

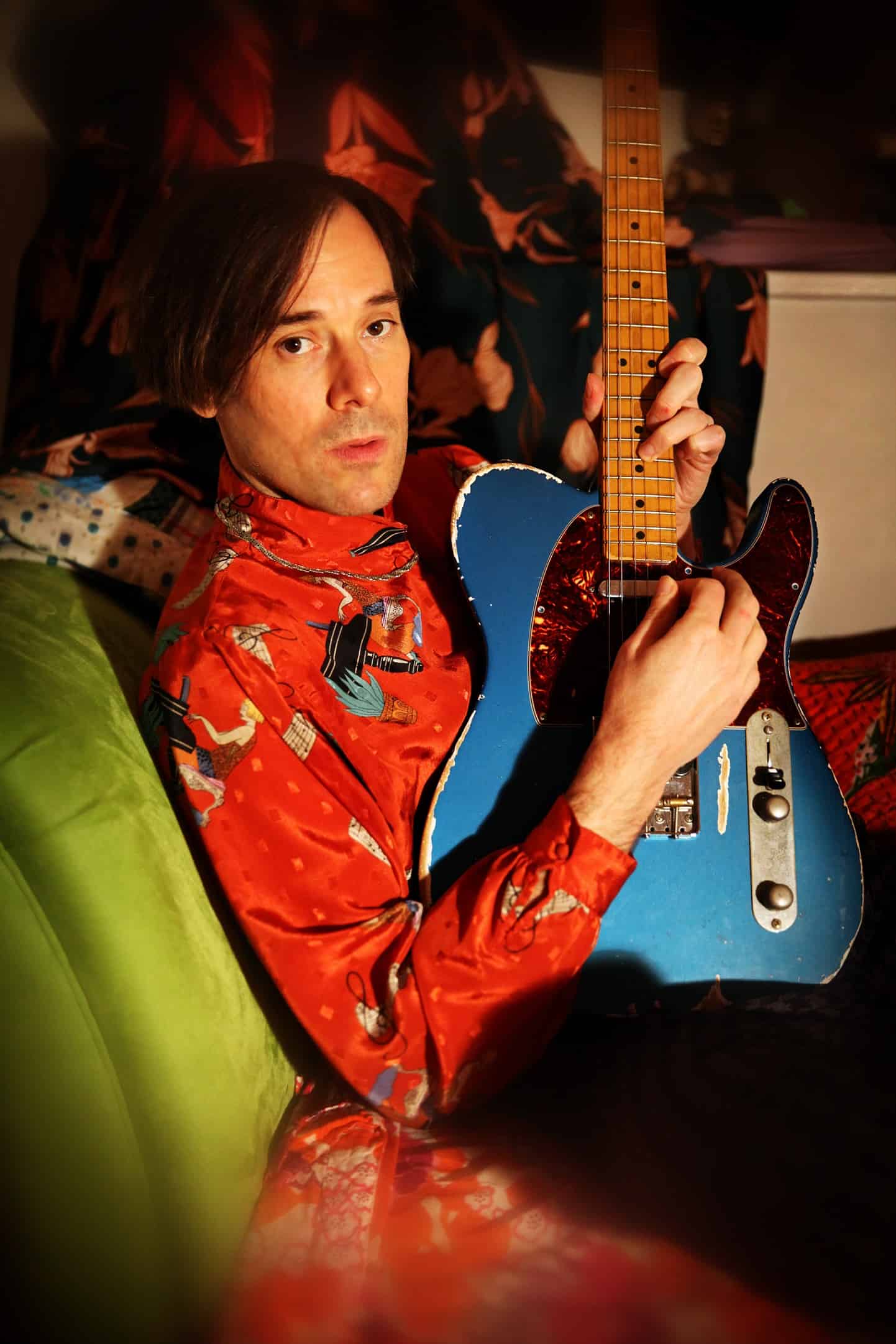

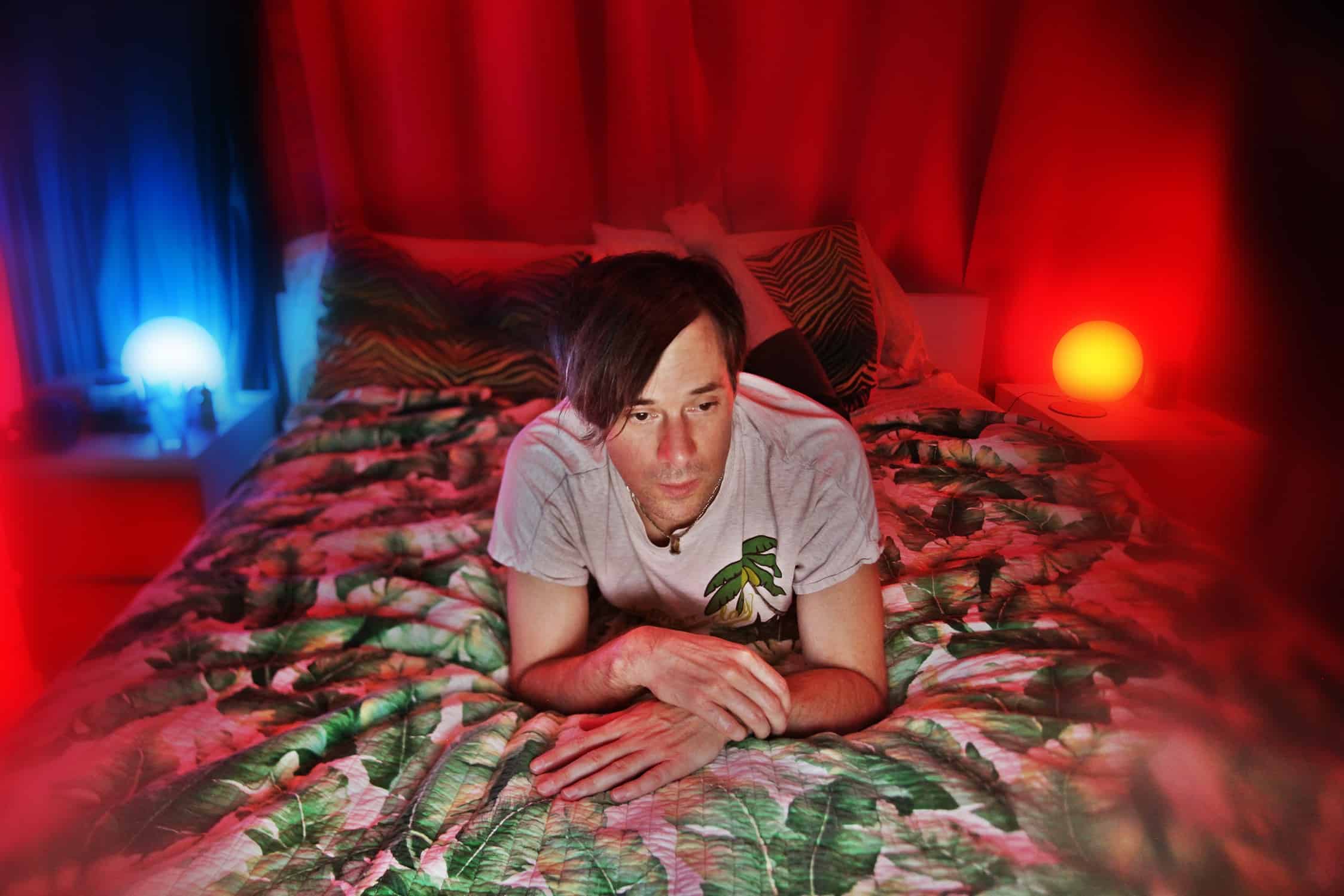

of Montreal frontman Kevin Barnes talks to Atwood Magazine about the making of his latest offering, UR FUN, and how his career has evolved over the last 25 years.

Stream: ‘UR FUN’ – of Montreal

We don’t need to think we’re on the verge of an apocalypse, necessarily, or if we are, that it doesn’t mean that we can’t enjoy life with what we have left.

It’s been 23 years since of Montreal released their first album, Cherry Peel. In that time, the longtime Polyvinyl residents have released a veritable menagerie of albums, collections of colorful songs ranging from highly experimental to highly danceable. Threaded through all of them is Kevin Barnes’ indelible knack for melody and turn of phrase, and his latest, UR FUN (out January 17th via Polyvinyl Records), is no different.

Though the album is much about Barnes’ struggle with dissociative disorder, it’s also about being “newly in love” with girlfriend Christina Schneider (Locate S,1), who features on the song “Gypsy That Remains.”

The album is kaleidoscopic and ’80s inspired, with streaks of Prince, punk, and new wave, but it’s wholly of Montreal. Atwood Magazine spoke with Barnes about complicated music that sounds happy, making music in politically frightening times, and the evolution of indie music.

I feel like we turn artists into cartoon characters or something, and don’t think of them as real human beings. Making that connection to them, just on a deep human level, is really special, and I think it’s so extraordinary that people can continue to put out albums deep into their 60s and 70s.

A CONVERSATION WITH OF MONTREAL’S KEVIN BARNES

Atwood Magazine: As of this year, your career now spans almost 25 years. How does it feel to be at this point?

Kevin Barnes: I don’t feel like that much time has passed, which I guess is a good thing. It doesn’t really feel like I’ve been doing this for 25 years, because it’s always a fresh challenge and I never feel like, “Okay, I got this.” You know, I’m always wondering if I’ll ever write a song again. And so it’s kind of like the same spirit, it sort of drives the project from the very beginning, so I don’t really feel burdened by the years or anything like that.

Your music has shifted styles throughout the years. What led you out of acoustic sounds into the more electronic sound you’ve explored over the last many albums?

Barnes: I guess just realizing that there’s so much new territory to explore in electronic music, and with computer music that you can infinitely tweak things and change the style and change the production quality and change so many different things just with one mouse click, and so it’s kind of really exciting to work in that field. But also like with acoustic music or whatever – people might want to call it organic, or analog or whatever – there’s also interesting challenges that go along with that and so I kind of bounce around a bunch, because when I first started getting into music, I was a very analog oriented artist and I started working on a cassette four track. When I first started making recordings and, you know, slowly worked up to analog tape machines, eight tracks, and 16 tracks and I have a 24 tracks now, so it’s kind of like, what I sort of started off with, and then sort of veered, like you said, into more electronic stuff and dancier stuff – you can still do that, obviously people did that in the 80s, you know with analog tape machines. But it wasn’t until Pro Tools and things like that became affordable for people that a lot of people started working in the digital realm. I feel like I took a lot of what I learned from the analog days into the digital realm, and I kind of use the computer like a tape machine anyways, but just kind of utilizing the editing abilities within that world, still kind of maintaining the analog vibe.

Do you feel like the physical way that you've recorded stuff has informed the project itself?

Barnes: Definitely sometimes. I mean if I decided I wanted to make a more collaborative record, then, often, I’ll do it on a tape machine just because it feels more exciting and I love the sound of analog tape and I love the sound of that kind of production. It just has this sort of inherent vibiness to it that you can’t get – like whatever the computer vibe is, it’s not great, but the analog vibe is great, but it’s kind of hard. I do a lot of stuff by myself when I’m recording and I do a lot of things like one instrument at a time and it’s kind of harder to work that way. It’s definitely slower on an analog tape machine, and so usually when I’m working by myself, I’ll work on the computer, and then if I work with other people I’ll do it on a tape machine. That’s how I prefer to do it, but it’s kind of too slow to do it that way if I’m working by myself.

UR FUN feels very 80s inspired, both pop and punk. Specifically, I’ve always heard a lot of Prince in your music. Is there a reason this album manifested this way?

Barnes: Maybe it’s just the music that I sort of fell in love with from an early age. I was born in 1974, so 1984 – I think that’s when Purple Rain came out – I was 10 years old. So I have a really special childhood connection to the sounds of the mid-80s, and the Cyndi Lauper record She’s So Unusual, but you know, that time period of Prince and sort of discovering music and discovering my love for it. And so yeah, I think that that’s just deeply rooted in my psyche and so maybe I associate that with like an innocence and a beauty that is connected to my childhood, and so when I think about a hopefulness and a positivity, I think about that time period of my life and about those records, so maybe that’s why. Because I’m, you know, sort of newly in love. And so that energy is there, as well, which is like a very youthful positive energy, and so yeah, maybe it makes sense that I would kind of explore that that quality of music with this record which is very much of a love letter to my girlfriend.

There’s a line in “Gypsy That Remains” that goes “You get me, nobody gets me, I get you, nobody gets you, you want me, nobody wants me.” You’ve shared on Twitter that this album is about navigating Dissociative Disorder. Can you talk a bit about that and those contradictions?

Barnes: Yeah, I mean, my girlfriend Christina is a songwriter as well and she, I think, is an extremely brilliant and incredible songwriter, but she hasn’t had a lot of success commercially speaking. She’s had a lot of artistic success, but not a lot of commercial success. And so, that is sort of a reference to her frustration with that and also like sometimes myself, even though I’ve had a good amount of commercial success, I still feel on some level misunderstood artistically, so yeah. Speaking to that, you know, that sometimes you have to like create a fortress around you and your partner and just stay positive, even if it doesn’t feel like the universe really wants you to exist.

the theme of UR FUN is that of a person (me) battling Dissociative Disorder, trying to navigate their existence amidst the careening walls of nightmare reality, and doggedly trying to keep themselves open to love and humanity ?

— of Montreal~she/he/they/them (@xxofMontrealxx) January 18, 2020

Many of your records have kind of an underlying story, whether it's a more explicit narrative, or not. Is there a story that was guiding you through this record or did it kind of come out later?

Barnes: I think it all happens in a sort of mysterious way. It’s very organic, but you don’t really know what it is until after it’s completed and you have a little bit of distance so you can look back on it. If I were to say like what the spirit of the record is, it is sort of what that Tweet was, as sort of working through my own psychosis and my own issues and trying to stay positive and appreciative of the good things that I have. And the great opportunities that I have in life and in love, and all that. But then there’s still that darkness that kind of creeps in, you know, that’s hard to ignore. Obviously the political climate impacts my worldview and my perception of reality. So, you know, if you’re sort of a “woke” person, it’s pretty hard to stay at 100% positive all the time.

You’ve been very vocal about supporting Bernie Sanders on your social media. I couldn’t help but associate “Don’t Let Me Die in America” with his fight for healthcare and equity. How do you feel today’s political climate has affected your music?

Barnes: It’s hard to say because obviously, in 1968, it would have felt like the whole planet was on fire, and especially within the country, that it was like on the brink of destruction. It’s kind of like, there are lots of periods in this country’s history where people would feel the way we feel now, that we’re on the verge of something really horrifying, and we need to step back and elect some empathetic, thoughtful, loving people to guide us. And the last four years have been the opposite of that, and definitely affects people’s state of mind and mental health. So yeah, I kind of struggle with that a lot because I go back and forth between feeling like I need to engage and feeling like I need to disengage. A lot of people feel that way on the left, people that aren’t, like, deep into a Trump thing. I think it’s like, it’s inevitable that it’s going to inform all of our assumptions and all of our worldviews and all of our mental health, so it’s sort of natural that it works its way into the music and then into the songs.

Do you feel like as a musician that you have kind of a duty to reflect that in your music? I know some people are very adamant about disengaging from that within their art and some go all in on it. So I'm kind of wondering where you stand on that.

Barnes: I think it’s a balance that has to be struck because unless you are a very political person, then like you said, you make art about that thing. I know people don’t necessarily look to of Montreal to fill that function, and I know of Montreal has always been, at least for me, a form of escapism and a way to sort of improve my life and create my reality through art, and through the therapy of the creative process. It’s not like you necessarily need to combine the two. But at the same time, I don’t think it’s necessarily that cool for people to act like things aren’t happening that are happening and to totally disengage seems sort of criminal in a way, because it’s almost like giving tacit approval to something. I feel like your voice needs to be heard and you do need to let people know where you stand, but do it in a way that doesn’t feel too obnoxious [laughs].

What’s the most meaningful song for you on this record and why?

Barnes: Well, I think the song that I’m most proud of is “You’ve Had Me Everywhere,” just because it’s harder for me to write love songs, it’s harder for me to write from that state of mind just because I feel actually more vulnerable when I’m singing something like that. Singing something truly from the heart that expresses something positive and loving and I guess I just find it easier to write mean spirited songs [laughs]. So I’m happy that I was able to create that and to express that to Christina, my girlfriend, and do it in a way that is totally pure and reflective of my feelings and, and to not have this sort of fear of rejection or let the baggage of the past creep in and kind of alter the purity of the message. So I think that one is my favorite. And I also like “Gypsy That Remains” and I mean, all the positive ones but I like them all of course, because I wrote them [laughs].

It's funny that you say that, because when I write music, I also am always finding myself veering towards heartbreak rather than an actual reflection of my happy relationship. Positivity feels like such a more vulnerable place to write from.

Barnes: Yeah, I think because a lot of the stuff that we’ve heard feels like not an authentic type of thing. Like all the love songs that I grew up with, they never felt real to me. It seemed like a thing that people did to be commercial. And that when people were saying something nastier than that felt more real. You know, like the whole punk thing or whatever. It feels more real than Barry Manilow. But I feel like John Lennon’s love songs feel real. There’s certain people: Leonard Cohen’s love songs feel real, Neil Young’s love songs feel real, Joni Mitchell’s love songs feel real. There are artists that I always believed. And so, you just have to kind of hope that people will believe you.

You’re an indie rock band, but there's so much like funk in your music in the bass lines and the grooves, and all of these different genres are kind of finding their way in there. I’ve always wondered if there are musicians that you feel tangibly impacted your writing, but that everyone would be surprised by if you cited them as an influence?

Barnes: I don’t know if people would be surprised by it, but I mean, maybe things like reggae music and things like that, like, Bob Marley. People wouldn’t necessarily know that I was into that kind of stuff, but it’s not that far removed from the funk influences and Parliament and Sly Stone and Stevie Wonder and Prince, and so I think it’s just kind of like a whole bunch of different people from like Charles Ives up to Madonna. There are so many different kinds of art that have influenced me and that I connect with and I kind of just bounce around a lot so I never really listen to the same thing for too long and I sort of fall in love with different time periods and different artists and I’m always sort of seeking news new sources of inspiration. So, even though like I’m sure for a lot of people they hear an of Montreal song and are like, “Oh yeah, that’s an of Montreal song.” But for me, I’m always trying to reinvent myself and try to do something new with each song, with each album. So, I guess, maybe what I’m really hoping, you know, when I die I want people to be like, “Oh yeah, this guy was an interesting artist, he wasn’t just a one trick pony.”

I was reading a Pitchfork interview you did in 2007, where you talked about the politeness of indie rock. I feel like that’s only become more true as indie rock has become mainstream and sanitized, and also kind of ambiguous – what has it been like to navigate through this genre as time has gone on?

Barnes: It’s been an interesting evolution because growing up, I was very much on the side of things where it’s like, yeah there’s mainstream, then there’s indie. There’s DIY, there’s underground music, and then there’s mainstream music, and mainstream music was just… I viewed it as just bullshit and not worth anything really, it just made it as a guilty pleasure in there but not really like legitimate art. And I feel like in a lot of ways I defined myself just as much by what didn’t like as what I did like. But now I feel like it’s changed to the point where everything has equal footing and. And I think Pitchfork has a lot to do with that, in the sense that they started reviewing mainstream records in the same way that they would that they would review underground records and treat them the same way as if they should be spoken up in the same light, you know, so it’s kind of interesting because to me that’s felt like the end of an era. I don’t know how it happened, but they kind of seem like the tastemakers in a lot of ways. And they can kind of control culture, on a lot of levels. Not so much anymore, but in their heyday they had more influence and power.

And so when they first started writing about Beyonce and Rihanna and Taylor Swift and just different mainstream people, and giving them good reviews, and then giving great indie bands reviews that are like, medium reviews, it was like, what’s going on [laughs]. Like what happened to our community? I thought that we were like, anti that mainstream stuff, and that we were supportive of the underground stuff but they kind of changed the rhetoric a bit, changed the narrative and seemed to kind of kill that, in a way. But then organically, all these bedroom projects were just sort of popping up and people were able to get their music heard through SoundCloud and Bandcamp and sort of avoid the whole major label world altogether. And then get traction through that and recognition through that and so that’s totally changed the music scene. But it’s funny because Christina and I were watching the Grammys the other night and they didn’t even talk about indie bands. It’s almost like they pretend that those two worlds don’t exist so obviously, there’s still like some secret organization that’s trying to keep the two worlds separated [laughs].

Pitchfork review

Vampire Weekend and Bon Iver being nominated was kind of funny to me, because I feel like they're the two indie bands that have somehow crossed over. Justin Vernon wasn't even there, because I remember watching him win Best New Artist in 2012, after he'd had this years long career, and he was just kind of looking around like, “Why is this happening…”

Barnes: Yeah, it’s funny how they’ll say like, you can win Best New Artist, even though you’ve been putting records for ten years. “No, you didn’t exist before because we didn’t know you were.”

I feel like, despite that divide, it feels like independent musicians and people that have been in that more underground scene have managed to maintain a more real community feeling rather than an industry one.

Barnes: Yeah, definitely. I feel like what of Montreal has been able to do is amazing. I never would have thought it would be possible, because it seems like most major label artists will maybe have like one or two albums that are successful. And then you never hear from them again. Like, what happened to that band? It just doesn’t exist anymore. But people like us who are sort of lifers, you know, we’ve had – we definitely are nowhere near as popular as we were around Hissing Fauna – but we’re still able to play shows and go on tour, and continue to put out records. I kind of identify with people like Guided By Voices or, you know, people that will just seemingly continue to put out records until they die. Sometimes you burn out a label or whatever and then there’s somebody else that believes in you that wants to work with you and just kind of keep doing it on whatever level is possible. I find that really inspiring and definitely something that I aspire towards, just continuing to work. It’s funny because I think there’s a lot of ageism that goes on – maybe it’s just as you get older you start to hear things a different way – but I remember thinking that, like, Neil Young’s later records like aren’t that good or Joni Mitchell’s later records aren’t that good, but now when I go back and listen to them, like Lou Reed’s later records, there’s so much great stuff on there. It’s just totally different from their early work, but it’s cool to hear an older person, like someone in their 50s and 60s, writing songs in a pure way and just getting into their head and thinking, what it’s like for them as an artist. Because a lot of times I feel like we turn artists into cartoon characters or something, and don’t think of them as real human beings. Making that connection to them, just on a deep human level, is really special, and I think it’s so extraordinary that people can continue to put out albums deep into their 60s and 70s.

I feel like what of Montreal has been able to do is amazing. I never would have thought it would be possible, because it seems like most major label artists will maybe have like one or two albums that are successful.

Yeah, I mean, if you listen to Blue compared to even just a few albums later, like her Mingus album, Joni just almost became a different person and you're watching that person's life happen in real time on such a public stage.

Barnes: Yeah, totally. And it’s funny too, like you can see when they had a successful record, and how it informs their next records. Neil Young’s a good example of that too, like, the records that followed Harvest are some of my favorite records, because I think it’s kind of like him reacting to getting mainstream success and being like, “Ew, I don’t like this,” and then seeing how it can actually be damaging to people. And it’s funny with music because we’re always sort of trying to have a hit – or not actively trying, but in the back of our mind you’re like, “Oh I hope record this does really well,” just because it makes your life easier [laughs]. And it seems like it would be a good thing, but in a lot of ways, commercial success is one of the worst things that could happen to an artist. I was thinking about that, how I remember all of the negative reviews but I don’t remember any of the positive reviews. And I realized that it’s because the negative reviews are actually inspiring in a twisted way, and the positive reviews are nice, but they’re not really memorable. Whenever I get a bad review, I’m like, extremely pissed off [laughs], but at the same time, like, I think that kind of thing is what propels me forward and pushes me to try to prove myself. But if someone just says you’re great all the time, then you’re like, “Oh I’m great, I guess I don’t need to work anymore.”

I remember all of the negative reviews but I don’t remember any of the positive reviews. And I realized that it’s because the negative reviews are actually inspiring in a twisted way, and the positive reviews are nice, but they’re not really memorable.

I always tell friends who go to see these artists at these massive arena shows, “I would so much rather see someone in a small venue where I can see the expressions on their faces and have the community feeling of all having loved a band for a long, long time.”

Barnes: Yeah, I can see that. It’s funny, because I never really go to see any of those shows. I have a daughter, she’s 15 now, but we’ve been to see Selena Gomez together and Halsey and people like that, which was fun because I’d never been to those kinds of shows, I’d never gone to an arena. Like you said, it’s a totally different experience just because there’s so much more money behind it, it’s more of a big production, and it’s cool to see like what people can do when they have a lot more money and a lot more resources, but at the same time, yeah, you kind of learn more from seeing a person on a small stage in a small venue, just on a Wednesday night on a tour, like, seeing what they’re up to and how they’re living on a daily basis.

In the spirit of this conversation, how do you feel that Athens, Georgia affected your musical growth and inversely, how your band impacted the city’s music scene?

Barnes: Well, I think it was really important for me to come here when I did. When I first moved here, I was 18 years old and I just graduated from high school, and it was a place that was like 10 hours away from where my parents were living. So it wasn’t like super far away, but it was far enough away where I could kind of establish myself as an individual. I was really fortunate to have met all these home recordists that were into the same kind of thing that I was into musically and there was a community of artists that I was a part of right away, and so that was extremely beneficial because before that, living down in South Florida, I had a couple of friends that were supportive, but there was basically no music scene to speak of. Nobody was into the kind of music or the sort of production that I was into, so I kind of felt like a total alien. But when I came up to Athens, there’s all these like-minded people and it was a really positive scene where we would, you know, play on each other’s records and play shows together and it was great. And so I think that kind of gave me this feeling that it was okay for me to be completely underground. You know, we felt strong together, we didn’t need the world to tell us that we were valuable, because we felt valuable just within our little bubble. So that enabled me to make the kind of records that I wanted to make, the sort of oddball records that definitely weren’t to the masses – I mean I don’t know who the hell they were for [laughs] – but it was just things that I wanted to make. I got that vibe from everybody else in that they’re just doing what they wanted to do and I think that was really cool to be a part of.

But as far as what my music has done for the current scene…I don’t really leave the house very much and I don’t really go to a lot of shows. I haven’t been a part of the music scene in Athens for a long, long time, so I don’t really know. If anything, maybe it’s just cool for people to see that there’s a band that has been doing it for many, many years and that can be inspiring in itself, to know that you can live in Athens and you can perform all over the world and come back to Athens, and it’s chill. The good thing about Athens is that it’s not super expensive to live here, so you can have a decent quality of life without having to make the kind of money that you need to make in New York or Los Angeles.

What do you hope people take away from this record?

Barnes: I guess just that we don’t need to think we’re on the verge of an apocalypse, necessarily, or if we are, that it doesn’t mean that we can’t enjoy life with what we have left, and we should appreciate what we have and sort of also work for a more positive future if possible.

— —

:: stream/purchase UR FUN here ::

— — — —

Connect to of Montreal on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Christina Schneider

:: Stream of Montreal ::