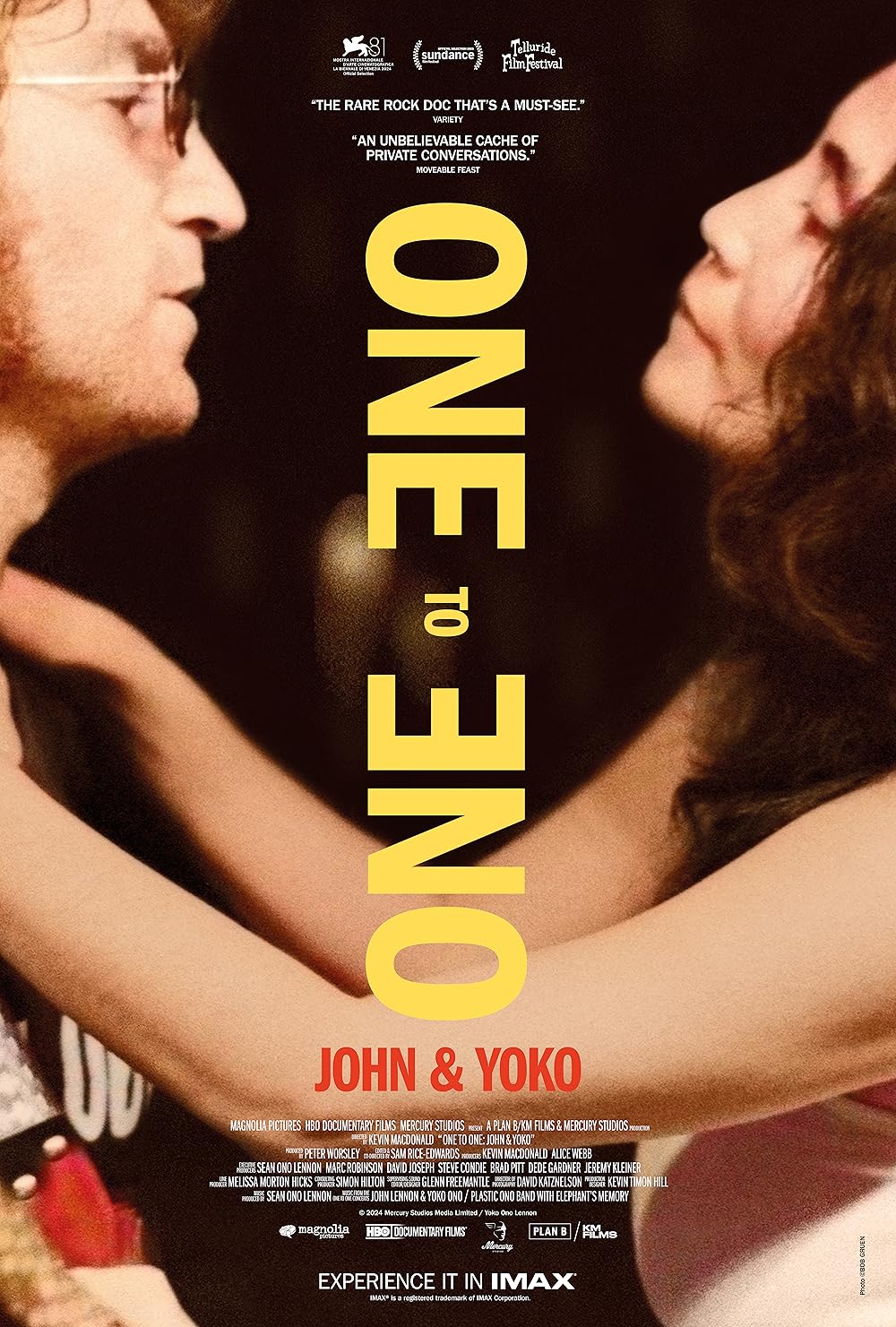

In anticipation of the forthcoming release of the remastered ‘One to One’ concert audio, Atwood Magazine’s Aidan Moyer revisits an April 2025 interview with Sam Rice-Edwards, the co-director of this year’s documentary covering the lead-up to the concerts, Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s real-time activism, and the potential for additional archival releases from this period.

“Imagine” – John & Yoko, Plastic Ono Band (live)

“Wherever You Are, You Are Here.”

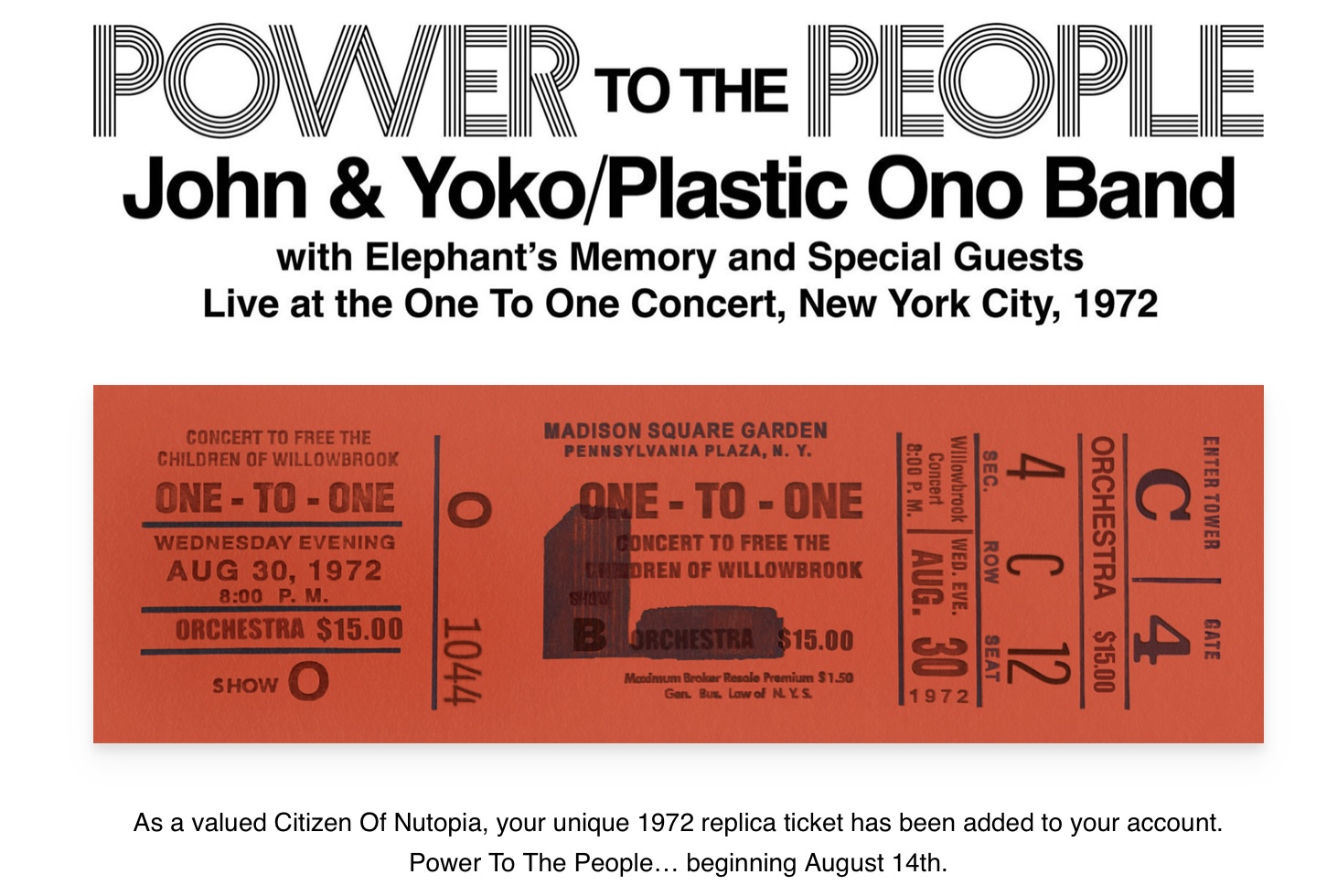

Conceived as a refuge from an ex-Beatle’s immigration woes, Yoko Ono and John Lennon founded the amorphous micronation Nutopia on April 2nd, 1973. Their screed decreed “NUTOPIA has no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people!”

On August 12, 2025, Nutopia arose again, as the Lennon estate’s email blast addressed the Citizens of Nutopia. Those who heeded the call were treated to a bespoke digital concert ticket modeled after the 1972 originals.

In celebration of Women’s History Month, Atwood Magazine’s Aidan Moyer took an advance look at One to One: John and Yoko, a new documentary spotlighting the Ono-Lennons and their 18 month residence in The Village circa 1972.

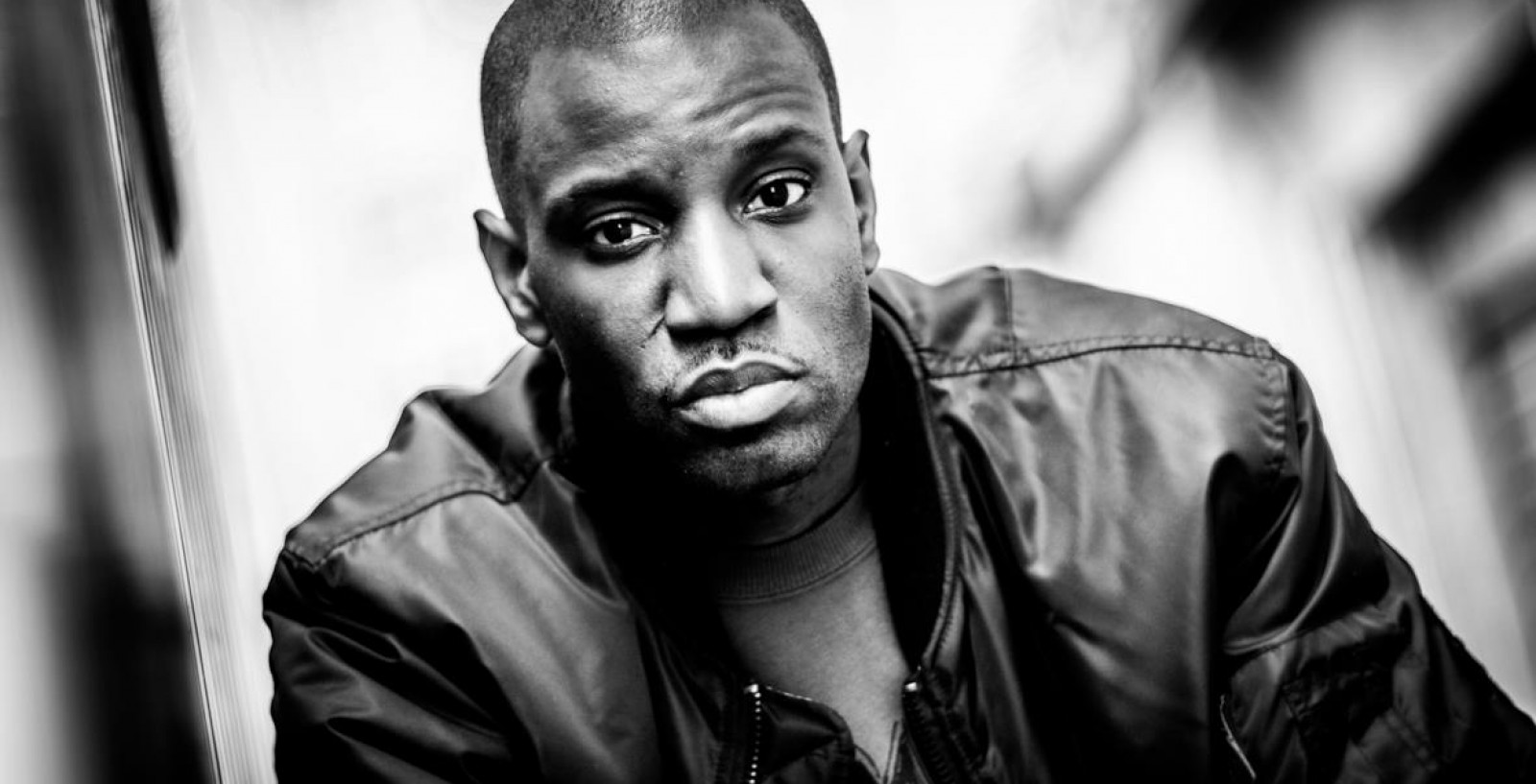

Upon publication, the opportunity arose to speak with Sam Rice-Edwards, the co-director of One to One. In the course of this conversation, Edwards toggles between the musical and visual backdrops of the film, the notion of John and Yoko unguarded, and striking parallels between the activism of 1971 and 2025. Our conversation is edited slightly for clarity.

A CONVERSATION WITH SAM RICE-EDWARDS

Atwood Magazine: Thank you so much for chatting! So you’re in New York for press right now?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah, exactly. I’m a little bit jet lagged, actually, just arrived last night but hanging in there.

I traveled to London for five days last summer and was not fully awake the entire time!

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah, it’s hard! Where are you based?

So right now I'm in Philadelphia, which was perfect because they just held the press screening last Thursday.I was able to Amtrak there very quickly. I’ve now seen ‘One to One’ three times because I got the press screener, watched it again with a bandmate of mine, and my girlfriend and I just went to the New York press premiere.

Sam Rice-Edwards: Ooh, amazing.

[An action figure of John Lennon falls over in the Zoom background].

That was the Ghost of John.

Sam Rice-Edwards: Oh, look at that, there you go! He’s just so impressed that you’ve seen the film so many times. That’s what it was.

My first question is an editing question. There's so much narrative heft to everything that's going on in Vietnam with Nixon, we see flashes of Angela Davis and stuff, but in the edit there's a lot of humor. The moment that I laughed out loud is when Lennon’s at a rally and says, ‘we need to bring the machines home.’ And then we cut to an ad for a washing machine. Lennon’s running through “Hound Dog” and we cut to Nixon tickling the ivories. Yoko said she was upgraded ‘from being a bitch to being a witch.’ How did you toe that line in keeping the narrative grounded, but preserving the humor that was pretty quintessential to the Ono Lennons?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah. I think you said it there, something that we really wanted to express, really, for two reasons. Because one is, as you just said, they were so playful as a couple, and as individuals as well. And so humor and playfulness and imagination was a huge part of who and what Yoko is, and who they were as a couple. But also, we were trying to present life in 1972, and the reality of life is that you have something very serious next to something very funny. In life, we bump into all these different things and actually if things are one tone, it actually becomes less real in a way and a bit monotonous.So we were really trying to mix things up, and in terms of how we found that line, it’s really just a kind of ‘suck and see’ kind of situation where you try stuff out and you feel like, “oh, that goes a bit too far”, or “that comes across as really disrespectful,” so it is just really feeling your way forward. And not shying away from things that surprise, because actually sometimes you do want things to be shocking or very surprising. Sometimes when you feel that, you’re like, “oh, let’s go with that. Let’s make a brave decision here”.

Yeah. The moment with George Wallace, the third time I still jumped a little bit.

I loved the framing of flicking through the television channels! I think there is a certain tendency to mythologize Lennon and Ono. They were couch potatoes! They loved channel surfing. And what I really appreciated is how naive Lennon was allowed to look here. There’s audio where Allen Klein is on the phone and John’s saying “why can't I sing a song about a prison riot”? And then you hear the breath being held over the phone. “Oh, sure. I'll write a song for the IRA,” just like McCartney did around the same time. There was that very gung-ho “Let's dive right in and then worry about the consequences later.” Were there any mandates about audio that might have been a little bit too ‘sticky’? And what was the intent with allowing John in particular to look so wide-eyed and so naive with some of the causes he was diving into in ‘72?

Sam Rice-Edwards: In terms of the Lennon estate, they really stood back. This is a film made by Kim McDonald and the producers, and Peter Wesley and Mercury Studios. They were obviously involved, but they very much respected Kevin as a filmmaker and allowed him to do what we all wanted to do to make a good film. So they were great in that respect and in lots of respects they were very helpful. And I think in terms of Lennon coming across as sort of wide-eyed, we wanted this film to be a chance for people to really get to know John and Yoko in a way that they are when they’re away from public view, and to spend time with them. [John] was someone who was extremely curious and adventurous, always trying new things. And there was a side [where he] allowed himself to dive into things, and I think to have that you have to have an element of naivety. And I think in the film, what we were trying to show is that they came to New York escaping the UK and the sort of vilification of Yoko and the breakup of the Beatles. They fell into a world that they loved and were very much influenced by the people around them, Jerry Rubin and that sort of gang had a sense that they could change the world. They became quite political, John, especially, and through the course of the film, they came to realize “maybe we can’t change the world on a big scale. We can maybe do some smaller things, some more human things,” such as the concert.

On the inverse of how Lennon walks back some of the “Black Panthers, White Panthers and all that jazz,” there's that image of Yoko in the bag doing performance art pieces, et cetera, this more mercurial spirit. And then you hear her on the phone, extremely tactful mitigating a lot of business stuff, mending fences. The pull quote for Atwood’s review, the poll quote was Yoko's, “Have you ever heard either of the three Beatles make a comment about me? It’s chauvinism.” And I'd imagine a lot of baby boomer readers will not be thrilled that's the pull quote, but that's the one that stuck out to me. Has Yoko seen this documentary?

Sam Rice-Edwards: I like to think she has, I don’t actually know for sure. But she’s stepped back from dealing with the Lennon estate and Sean Lennon has really stepped into that role. I would like to think she has, but really Sean was the person who we were connected to.

Wonderful! It's a massive job to contextualize two of the largest artists of the 20th Century and share their last name, and handle the audio remixing and a lot of PR, they’re huge shoes to fill.

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah, Sean was great, I have to say. He was very supportive of the film.I was in a screening where we played it for him for the first time, and it was actually quite moving watching it with him because obviously it’s so incredibly personal for him. He did a fantastic job with the audio. The concert was amazing, but there were a lot of problems in the way it was recorded and shot and so forth. And so there was a lot of work to be done. And he really bought the sound to life

Did I see Paul Hicks's name there as well in the audio mix?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Possibly, I’m not sure. Paul Hicks, what was he doing. with Sean, you mean?

I think it was something with the audio. I know that Dhani Harrison works a lot with Paul Hicks, and I flagged the name in the credits.

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yes.

Yeah, it's such an obvious thing to say, but what a voice. Lennon just had that like pure, ripping rock vocal. “Instant Karma” has not been outta my head, the Wurlitzer piano has just been on loop. Is there going to be an audio tie in a ‘Live in New York’ companion to the film? Or is it, will the audio just live as the soundtrack?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Do you mean ‘will there be a release of the concert’? Yes. I think yes, that there will actually be a release of a concert film. But I dunno when that’s coming out. Obviously we haven’t got the whole concert in the film, the concert is at the heart of our film but it’s not a ‘concert film’ as such. You go there and it’s a great cinematic experience, I think, to watch the film because you really, in the moments where we delve into the concert, you feel like you are at the only concert that John did after leaving The Beatles, ever.And so it is that experience, but the film that we made, hopefully, everyone feels is bigger than a concert film in a way. It’s more about the time and about John and Yoko, who they were as people and what was happening in 1972 and how that weirdly parallels to now. So I think that is a bigger film than just the concert.

(Note: A four-track EP for Record Store Day was followed by an August 12th teaser for the ‘Citizens of Nutopia’ that the concert’s audio release is forthcoming).

Oh, speaking of parallels to now, what luck – not luck, obviously- but the concert that the choir gave to Nixon where they held up the ‘Stop The Killing’ banner. And what was it, four or five weeks ago that a choir went to the White House and sang the song from Les Miserables (“Do You Hear The People Sing?”) That is so eerie, how pertinent all of the “Free the People, Stop The Killing” is, it's about ‘Nam, but it's also about now.

Sam Rice-Edwards: It’s distressing. It was a very strange thing because, immediately. we saw the parallels between then and now. I say now, a year ago, a year and a half ago, or maybe a little longer, we could see the sort of fractures in society were similar. The polarization of right and left and the same issues were at the fore, gender politics, race, environment. So, we could see the parallel straight away, and it’s something that we wanted to reflect, but we didn’t really, it only became clear how hugely parallel it was becoming as we were editing the film. And after the film was finished, as Nixon and George Wallace somehow represented Donald Trump. And then, there was an assassination attempt, and the parallels went on and on. Nixon’s landslide victory and so forth. So, it became quite strange, actually.

So, a timeline question: Last summer, there was a box set that was supposed to be for Mind Games, but there was Some Time in New York City material folded into it. And there's a letter from the time period of this film when Lennon was talking about, “oh, we can get Dylan for a tour, and he met with McCartney at Bank Street.” There's a letter from around the time they wrote the songs about Ireland inviting Wings to join the one-to-one concert. Timeline wise, was that material something you were aware of or did that come to light after editing was already underway?

Sam Rice-Edwards: I think, I can’t remember specifically, but in the sort of recess of my mind, it rings a bell, and I feel like we knew about that at the time. The thing is that, there are a lot of other facts out there and letters and paperwork, but really the film that we set out to make was a visual cinematic film, and we wanted it to really give people a time capsule and a slice of John and Yoko at that time without delving into information and showing stills of letters and that sort of thing. What we have is all film or video of the time. If there were things that we knew, but we didn’t have any material that we could use, then really we couldn’t get them into the film. They were interesting to know but it didn’t work in the format of the film.

Absolutely. In terms of using all available audio and video, there are some wonderful cameos. I knew that Stevie Wonder had been at the concert, but the way he just slides into frame and absolutely rips “Give Peace a Chance” is wonderful. I wasn’t shocked per se, but it was interesting to hear May Pang's voice. She put out her own doc last year. Then, Phil Spector pops into frame quite a bit… and Alan Ginsberg has his share of retroactive controversies as well. Was there any thought paid to how any of the players look in retrospect, or was it all a diary of what was happening in the moment, and you cast to one side ‘what was to be’?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah, I think it’s a really good question and it’s something that we spoke about a lot. It’s not a film that looks in retrospect at what those characters did after, or what came to light and that’s undoubtedly very important stuff to talk about and process, but that’s not the film that we were making actually. We were making a film that was in the moment, at the time. And what people knew then. Even to the point where we didn’t title people, people popped up on screen. Angela Davis, she’s just not titled at all. If know who she is, then you get it. If you don’t know who she is, you just get a feeling for that sort of thing happening at that time. We were trying to create the world that John and Yoko saw at that time, and they didn’t see name titles, they didn’t know any of the stuff that we know maybe now about Ginsberg or whoever, in retrospect. So, we were really trying to paint a picture of that moment.

In line with that, the end of the main narrative pans out from the TV in Bang Street and sirens pass by. And Jim Kelner alludes to, “We're not trying to get ourselves shot here.”

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah.

Is even though this is a narrative time capsule, were the sirens deliberate and an allusion to where the story is heading? I'm curious about that choice, the sirens at the window at the end.

Sam Rice-Edwards: Yeah, it’s a sort of film that you can pick out what you want from it, not in a bad way, in a good way. It’s all there and you can make the connections and everyone will make different connections. We decided very much to be in the timeframe of them at Bank Street and that, that felt like a natural period for the film to be in. And we didn’t want to rehash stuff about John’s deaths, which has been so well documented in many films. But that’s not to say that it’s not alluded to in ways that you mentioned, the sirens not so directly, but obviously Jim Kelner had a sort of foreboding feeling with that conversation that they had. So it’s in there in essence, but it’s not a fundamental part of the narrative of the time, of the film.

“Freda Peeple,” which plays over the credits, that's the only selection that postdates the narrative, that's a track from ‘73. And then everything else is Sometime in New York City. I could be wrong there, but-

Sam Rice-Edwards: It’s either “Some Time in New York City” or the concert. Because obviously a lot of the songs were [older], “Come Together” and so forth. But in terms of after the time period [of the narrative], I think that he wrote that song in the time period, but it came out later. And also the song just before it was just something I forgot the name of [“Mind Games”], so those two at the end, they come out after our time period, but they were written during the time period. So we felt that they were apt for the ending. And also they had the right sort of ‘feeling’ and, “Freda Peeple” in a way was like looking back at the film and summarizing John and Yoko’s feeling of what they were trying to say through the film.

“Freda Peeple,” by coincidence, is probably my favorite solo Lennon song. I was very happy that made it into the credits.

Sam Rice-Edwards: It’s funny that a lot of people love that track, I mean, it’s obviously a really well-known track, but it’s not one that’s you think of straight away when you say, “What is your favorite. Lennon solo track?” But we kept on meeting people who were like, “I love that track.” So you’ve got some friends out there!

Yes, excellent! Being mindful of time, this is my last question. I jumped out of my chair when I saw some of the home video footage in the doc. As great as the concert was, the shaky seventies video camera of the Lennons in Cambridge at the feminist conference, and inside the Dakota, it’s pretty jaw-dropping. Is there more of that footage, and could that be a project unto itself?

Sam Rice-Edwards: Obviously the stuff that, the Portapak stuff, that’s the format that the black and white stuff in Cambridge and at the feminist conference was shot on.It’s this old format called Portapak. There’s obviously more tapes of that, we had a lot of that footage, but actually it’s all the same stuff with them driving around and so forth. So really I think, we told the story and what we felt was the best way from that footage.

It is not really a question for me. I think it’s a question [where] you need to get hold of the Lennon Foundation and see what else they’ve got in the vaults. But I don’t know, I think all the best stuff that we had is in the film. Of that time and, maybe that there’s not that much stuff that actually exists of [the Ono-Lennons] at that time. We were really pleased to have found all the stuff that we found that’s in the film and that, and it feels very rich. There’s only a finite amount. I’m sorry. I feel like I’ve given you a really bad answer there.

No, not at all!

Sam Rice-Edwards: So something that happened two or three months into the edit was somebody from the Lennon estate called up guy called Simon Hilton, who had been helping us a lot. And he had been out in New York at the Lennon Archive. He’d been walking around the archive and found this box on a shelf, not labeled. And he looked in it and found these tapes. Anyway, he gave us a call and he said “I think we’ve got something you might be interested in.” And it turned out that it was all the phone conversations they had just been sitting on, all this time for the last 40 or so years 50 years! And no one had really looked at them. So that was a really kind of magical moment. Once we received those, we instantly knew that they were something very special. ‘Cause you never hear John and Yoko talking like that, where they really don’t feel like they’re being listened to, they’re not that out of the public eye. It was instantly very revealing about who they are. It was a great moment to receive that archive.

That's beautiful. Born in paranoia, but turned into something narrative and beautiful all those years later!

Sam Rice-Edwards: Exactly. That’s a very John and Yoko thing to do, isn’t it?To turn paranoia into something more positive.

“Don’t despair, paranoia’s everywhere.” Thank you so much for taking the time to talk about the doc, I will probably see it a fourth and fifth time!

Sam Rice-Edwards: Look, thank you so much. And yeah, it’s really great to hear that you enjoyed the film. Thank you, take care!

— —

One to One is now streaming on Apple TV, Amazon Prime Video, Fandango at Home and YouTube.

— —

— — — —

Follow John Lennon on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Connect to Yoko Ono on

Facebook, 𝕏, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Aidan Moyer

:: Stream John Lennon ::

© Aidan Moyer

© Aidan Moyer