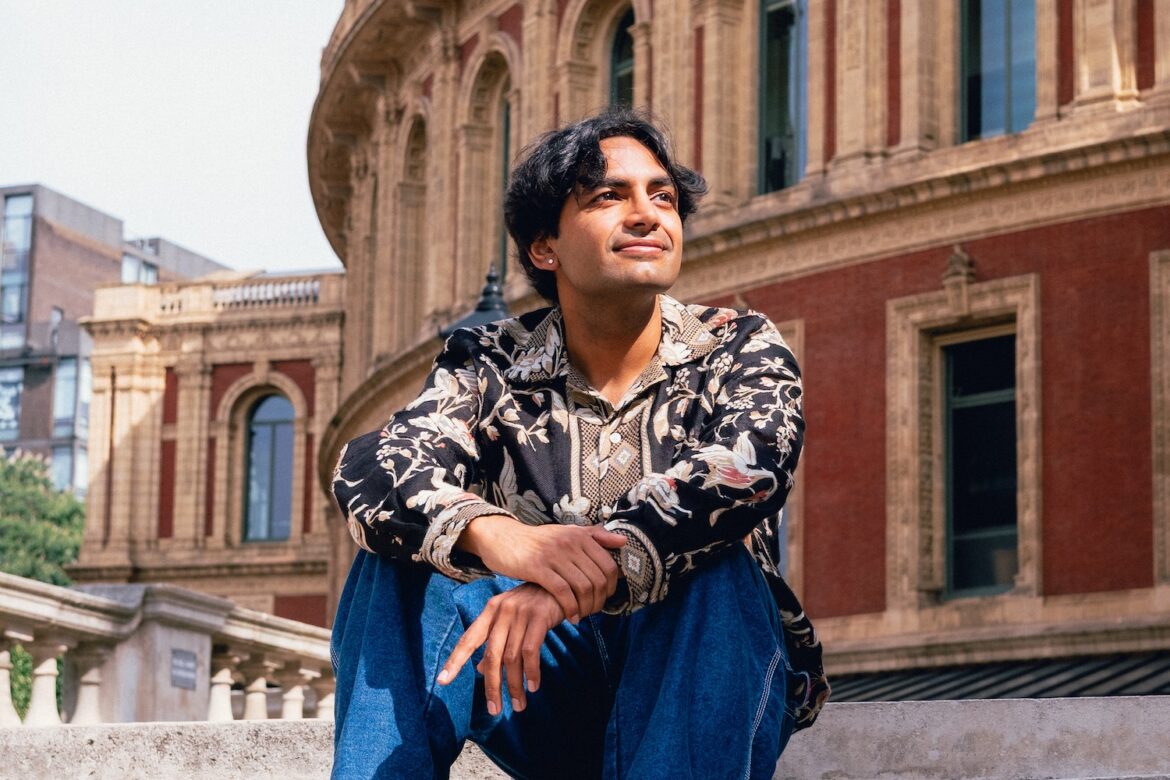

Emerging from a rich tapestry of cultural influences and personal evolution, Jeeves is a bold new voice in the singer/songwriter landscape. Drawing from his South Asian heritage and a global musical journey, from Hindustani vocal lessons to Nashville studios, he fearlessly blends genres, languages, and emotions into a singular, timeless sound. Jeeves reflects on his artistic evolution, the challenges of navigating the Western music scene as a South Asian artist, and the cathartic power of songwriting that connects us all.

“Where Did All the Good Men Go?” – Jeeves

With his heart in his hands and a message that bears repeating, Jeeves has reemerged with a deeply personal and long-awaited new single, “Where Did All The Good Men Go?” – the first taste of his upcoming debut album Now or Never, slated for late 2025.

Written in 2017 during the cultural upheaval of the #MeToo movement, the track confronts the complex search for positive male role models in today’s world. Jeeves’ poignant lyrics and heartfelt delivery invite listeners into an intimate reflection on vulnerability, identity, and healing.

The artist’s journey is as diverse as his music. Named after the Sanskrit word “जीव” (life), Jeeves navigates a global creative path that spans Los Angeles, New York, Nashville, London, and Stockholm. His debut EP, Live at Cove City, recorded in one take with legendary saxophonist Richie Cannata, showcased his fearless approach to storytelling and musicianship. Now, with Now or Never, Jeeves continues to explore themes of courage, hope, and connection, inviting listeners to embrace vulnerability and find joy.

“Where Did All The Good Men Go?” blends the lyrical intimacy of Ed Sheeran with the refined musicianship of John Mayer, seasoned with Jeeves’ unique “brown sugar finish.” Recorded in Nashville with Grammy-nominated guitarist Charles Myers (Yebba) and featuring drummer Aaron Sterling (John Mayer), the song is elevated by a cinematic string arrangement from Shaan Ramaprasad, whose impressive credits span A.R. Rahman to Chance the Rapper. This stellar collaboration results in a sound that’s both richly textured and emotionally raw.

Jeeves shares that this track was nearly shelved due to its emotional honesty. “I almost didn’t release it because I was afraid of its vulnerability and honesty,” he says. “But I healed parts of myself through its writing, and I hope it does the same for others.”

The song’s enduring resonance is underscored by its live debut at Los Angeles’s iconic Hotel Café, a milestone that highlights Jeeves as part of a vibrant new wave of South Asian voices transforming the American singer-songwriter tradition.

As Jeeves prepares to release his debut album, “Where Did All The Good Men Go?” stands as a stirring anthem of reflection and renewal. It is a testament to the power of music to heal personal wounds and spark collective empathy, a timeless question delivered with raw emotion and a sound that bridges cultures and generations.

Atwood Magazine spoke with Jeeves about his musical journey, the voyage to “Where Did All The Good Men Go?,” his vision for a debut album that blends soulful introspection with cross-cultural influences, and the fearless vulnerability that shapes his music and message.

— —

:: stream/purchase Where Did All the Good Men Go? here ::

:: connect with Jeeves here ::

— —

A CONVERSATION WITH JEEVES

Atwood Magazine: Let’s start at the beginning. What first drew you to music, and how did your Indian-American identity shape your early experiences as a songwriter?

Jeeves: Legend has it, my mom would sing lullabies to help me sleep – but instead of drifting off, I’d stare wide-eyed in wonder. Music was everywhere growing up. My dad, part of the founding team at PortalPlayer (the startup behind early MP3 players like the iPod), would jam in the garage after work with his band. I was their three-year-old groupie, grabbing the mic and mimicking songs in English, Tamil, Hindi, and Malayalam.

Our home was filled with prototypes of MP3 players loaded with everything from A.R. Rahman and Yesudas to the Beatles, Green Day, and Clapton. My grandfather was a trained Carnatic vocalist, though his dreams were stifled by colonial-era racism. My father chose a different path – tech over music – because back then, an Indian man dreaming of stardom in America felt impossible.

Now, as a first-gen Californian, I feel deeply fortunate. I carry the thread of those generational dreams and am free to sing songs that blur genres – songs of freedom, unity, love, and joy. That’s the gift of progress, and I don’t take it for granted.

Your name, Jeeves, comes from the Sanskrit word “जीव,” meaning life. What does that name mean to you artistically and personally?

Jeeves: Glad you asked! Jeeves comes from the Sanskrit word “जीव,” meaning life, which feels deeply personal and meaningful. Growing up, “Ask Jeeves?” was a fun nod to curiosity, and as a drumline leader, I kept everyone marching to the beat – just like the name suggests. In London, people connect it to P.G. Wodehouse and call it a “strong British name,” which I love. Artistically, Jeeves is plural in English, symbolizing an invitation for everyone to see themselves in my music. Ultimately, my life’s work is about unity – “We are One,” not just in the Vedic sense, but as John Lennon meant it.

Growing up in California, who were the artists or genres that most influenced your musical journey?

Jeeves: I have two ears, one mouth, and an empathetic soul, so I’m always under the influence. To surprise, there’s this artist from San Diego, Jason Mraz, whose avocado farm added guacamole to both my Chipotle and my songwriting. I began by scatting and imitating “I’m Yours” and the first concert I ever saw was, “Love is a Four Letter Word” in Berkeley CA; I started winning singing competitions by singing the A-Team by Ed Sheeran, and then we learned how to play all of John Mayer’s songs on guitar. In Jeeves lore, they might be a holy trinity for unknown reasons.

I’m always open, and I listen to music in every language, and my friend Joe always reminds me with love that genres are not real: Ravel, Bill Evans, Juanes, BB King, Clapton, SRV, Sinatra, Juan Luis Guerra, Dolly Parton, A.R. Rahman, Elton John, Piccioni, Andrea Bocelli, Daft Punk, Beatles, Joni Mitchell, Bon Iver, Ólafur Arnalds, ABBA, The Mamas and Papas, Fleetwood Mac, Justin Timberlake, Quincy Jones, Pharell, Timbaland, Ben Böhmer, Zedd – off the dome.

You’ve lived and worked in cities like LA, New York, Nashville, London, and Stockholm. How have these places shaped your sound and songwriting?

Jeeves: Each city left its mark on me.

Los Angeles taught me to be visually honest. Amid all the glitz of Melrose Avenue and Hollywood, I discovered that songwriting isn’t about seeking approval – it’s about telling the truth. I began writing songs like a director crafting a three-minute film, seeing scenes unfold in my mind. LA made my songwriting cinematic, glamorous when needed, but always rooted in authenticity.

New York brought grit and magic. After reading Just Kids by Patti Smith, I saw myself as a NYC songwriter. There’s real history bleeding into my records – especially with Richie Cannata on sax, who’s played with Billy Joel and the Beach Boys. One of my guilty pleasures is blasting that track in a cab while crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, skyline glowing.

Nashville is where I reconnected with the soul of songwriting. It’s a place where a violin turns into a fiddle, where every lyric matters, and where Charles Myers – my collaborator and catalyst – has pulled me into a richer, more country-influenced world. It’s challenged me, humbled me, and expanded my sonic palette in unexpected ways.

London drew me in with its elegance and eccentricity. I stayed in Kensington, ran through Hyde Park, went to the opera, and soaked in stories from cab drivers. But it was Cornwall, not the city, that shaped my album Now or Never. My producer Alfie Hole welcomed me with apple crumble, a bonfire, and acres of silence. We recorded under starlight, with owls (yes, actual owls) making cameo appearances on the tracks. Our mixer, Sam Okell – who worked on Harry Potter, Marvel, Amy Winehouse, and the Beatles – gave the record a cinematic touch. We wanted the songs to sound like the Ministry of Magic.

Stockholm is pop perfection. Home to Max Martin, ABBA, and the architects of melody-first songwriting, it changed how I view pop. I learned Swedish (Hej! Tack så mycket! Skål!), fell for the city’s elegance, and found beauty in its structure – where every song follows a code, yet still feels free. I dream of returning to make records with synths whispering secrets from ABBA’s golden age. Also, Savan Kotecha is one of my biggest inspirations – an Indian-American dreamer who made it in global pop. I hope our paths cross in that melodic Nordic wonderland.

You recorded your debut EP Live at Cove City in a bold one-take-per-song format. What inspired that approach, and how did it challenge or liberate you as an artist?

Jeeves: It was a mix of boldness, naiveté, and the desire to show the world exactly what I sound like live. After watching Jon Bellion’s Live at Cove City concert, I thought – what if we did that? No AutoTune, no post-production safety nets, just one shot per song. Scary? Absolutely. But I don’t negotiate against myself, so I went all in – live band, string quartet, background singers, two piano players, drums, bass, all on video.

The real turning point was when I picked up the phone – not an email, a call – and Richie Cannata, legendary saxophonist for Billy Joel and the Beach Boys, answered. I told him my idea, and he said, “That’s crazy… but let’s talk.” After hearing my demo, he surprised me by offering to play a sax solo. Billy Joel’s River of Dreams, which was recorded at Cove City, was one of my dad’s favorite songs, so that moment felt cosmic.

Recording it changed me. I let go of control. I told Joe on piano to forget the charts and just play. I encouraged the singers to improvise, smiled when Shaan Ramaprasad mimicked my vocal line on violin, and stood in awe as Richie lit up The News with his solo. We hadn’t even rehearsed as a full group before that day – it was pure instinct, energy, and trust.

That session taught me the beauty of imperfection – Japanese wabi-sabi, baby. I used to over-arrange everything. That day, I killed my ego and let real music happen. You can hear us feeling our way into something honest. It’s a snapshot of a moment that will never happen again, and that’s what makes it timeless.

On August 9th, Live at Cove City turns three – and I still listen to it with gratitude. It’s a reminder that I’m no longer alone in this. I found my people. And I found my freedom.

Looking back, how would you describe your evolution from that EP to where you are now, with this debut album on the horizon?

Jeeves: Wow, I can’t wait for the world to catch up! It’s been a non-linear, fairytale-like journey, part memoir, part miracle. I’m incredibly proud of myself. In fall 2023, I quit my day job and went all in on my music career. It was a Now or Never moment – and what followed felt impossible and improbable, like scenes from a movie.

Two moms I met on a NYC playdate somehow got my music into the boardroom of Universal Music Group. I debuted at the Hotel Cafe just three months after moving to LA. A BTS drummer showed up at my studio session by chance. I fell in love with a fearless woman and singer in London who inspired me beyond words. A train conductor shared my music with friends at the BBC. I met the best Hindustani vocalist in India – now my teacher. We lit a bonfire in the UK countryside to mark the start of the album recording. A mysterious CEO’s call sent me to Sweden. I stepped into Charles Myers’ studio in Nashville. I recorded a song in David Bowie’s producer’s studio. And I sang for Virgin Atlantic flight attendants who gave me priority boarding and special care.

Life is different now. I’ve blossomed as an artist and fully embraced who I am – no longer seeking permission, unapologetically myself, with a sparkle in my eyes. I intentionally improved my physical health in LA, shedding 51 pounds and running a 6:11 mile – I like to call it the Benson Boone effect. My heart’s been broken and healed; I’m single, content, and paradoxically thriving in solitude. Though I often feel misunderstood, it no longer weighs on me – I’m filled with empathy, love, and a deep connection to humanity. Strangers’ kindness moves me daily.

Sonically, this new album blows my EP out of the water. There’s a Spanish track that blends Opera and Bad Bunny vibes, a Quincy Jones-inspired disco tune, a Nashville rock song with country influences, cinematic Scandinavian ballads, and a French-infused pop song. It’s a globe-spanning journey through how I see the world. Most surprisingly, the album feels cohesive – meant to be listened to start to finish – with the thread that ties it all together being shared humanity and my own evolving story.

How have you navigated the industry as a South Asian voice in a predominantly Western singer/songwriter landscape?

Jeeves: Icons like Shah Rukh Khan, Priyanka Chopra, Anjula Acharia, and Savan Kotecha inspire me by showing how art can connect billions worldwide without boundaries. A pivotal read for me was Life Unlocked by Dr. Srini Pillay, which flipped a switch and made me fearless in this career. I see my identity and skin color not as liabilities but as my greatest assets.

I embrace boldness, inspired by Jung’s “Only boldness can deliver us from fear” and Kierkegaard’s “To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily, not to dare is to lose oneself.” I rewrote my inner narrative: I’m not a model minority or victim, but a rare gem – an Indian-American boy from California, making music at Hollywood’s Hotel Café and adding to a vibrant multicultural tapestry.

My music isn’t about fitting into a box or blending Indian elements just because of my heritage (though those are coming!). True inclusion means the freedom to create without race, skin color, or gender shaping the conversation. I’m excited to break barriers – singing in every language possible – and live Tolstoy’s idea that “art is a means of communion among people.”

This new single is described as eight years in the making. Why did it take so long, and why release it now?

Jeeves: Did I really hold onto this idea for eight years? Not exactly – I probably should have quit! The chorus came from a raw, emotional place, written while crying in the shower, planting the seed for something meaningful. Lyrically, I explored many perspectives of people I love but eventually decided to write from my own experience – my yearning for positive role models and unresolved trauma – while leaving space for others to relate.

Musically, I kept it private for a long time because sharing something so vulnerable – “even with all my friends and family, don’t feel you’ll understand me” – is hard. It takes trust to open up like that, especially when the risk is being misunderstood or pitied rather than empathized with. The collaborators I brought in now know my story intimately, and we’re sharing it with the world.

Why now? This question is timeless, but today’s division and lack of positive role models make it more urgent. I’m not trying to write a topical anthem; I want to create something timeless that connects. If this song can comfort just one person, it’s worth it. And fun fact – Sabrina Carpenter’s “Manchild” asks a similar question – can you tell her “I feel you” for me?

You’ve said you were initially afraid to release the song because of its vulnerability. What part of yourself did you confront while writing or recording it?

Jeeves: Shame, guilt, trauma, honesty, interconnectedness, agency, and self-acceptance. The number of times I cried in front of a microphone was ridiculous; btw the toxic masculinity of “men don’t cry” still shows up in my social media comments and I just hide them and laugh. Charles and I had a system, though, where I would tell him “zone” and we would just record without an expectation of performance. He just understood me, didn’t say a word, let me express my heart, and gave me a hug afterwards! What a man.

In the West, we hold shame regarding our struggle, but we never heal in isolation. We heal when we share our stories with people we trust. In my case, I’m doing so publicly without fear of judgment and unapologetically. I reclaimed my agency, power, and I’m light as a feather. We went from private, to friends and family, public in a small venue, to global. There are 1% of people who are not too kind to me for it, but I’m also receiving a lot of love 99% of the time. Worth it!!!

The song was written in the wake of the #MeToo movement. How did that cultural moment inform the themes of this track?

Jeeves: Let’s just say that there are a lot of people I love and care about in my community who have been affected by the cruelty of men in the world. The movement amplified what was already in my heart, and the abundance of stories that came to our public consciousness probably elicited the very question, “Where Did All The Good Men Go?” in all of our hearts. The opening lines are indeed, “after all the violence, after all the silence, I found myself in pieces on the floor, no one to confide in, why am I crying? I said ‘I’m fine,’ I feel I’m lying.” Silence breeds disease, and for those who don’t wish to speak, I hope the music meets them where they are.

There’s a powerful line of inquiry in the title itself - are good men the rule or the exception? How do you personally wrestle with that question?

Jeeves: Isn’t it a bit of a faux pas for an artist to answer that? I’m unusually optimistic, despite many men in my life letting me down. Pain changes how we see the world, and I don’t believe in labeling people simply good or bad – everyone has light and shadow. As Carl Jung said, to be whole, we must acknowledge our dark side. Marilyn Monroe put it well: “I am good, but not an angel. I do sin, but I am not the devil.”

There are good men everywhere, and it’s vital to believe in and nurture that. I worry that some discussions around masculinity alienate men, creating shame or guilt, when really, the sexes aren’t at war. We need good men more than ever – something feminist author Bell Hooks might agree with.

In the song, I ask for something to believe in, and I choose to believe in good men. Writing this song was part of healing myself and holding faith in humanity – and in the friends and loved ones who’ve profoundly changed my life for the better.

You collaborated with some incredible musicians like Charles Myers and Aaron Sterling. What was the recording experience like in Nashville, and how did they shape the final sound?

Jeeves: Walking into Charles Myers’ studio in Nashville felt like stepping into a dream I didn’t realize was already unfolding. On the wall was the plaque for My Mind by Yebba, released under Ed Sheeran’s Gingerbread Man Records. Charles has toured with Ed, and nearby was a setlist from a John Mayer tour – because, of course, he’s played with John too. What blew my mind is that before I ever met Charles, I had unknowingly seen him open for John Mayer at the Chase Center in San Francisco. I was in the audience, and my future producer was on that stage. I thought I was taking the London Circle Line to get where I was going, but somehow, it led me to Nashville.

We’re a creative match made in heaven. Charles is already one of the best producers in the world – his ear, his taste, his instincts, and even his passion for analogue film photography inform everything he creates. He thinks about music in layers – not just how it sounds, but how it feels and looks live. One of our songs began as a piano ballad, and then Charles came in with a gritty, iconic guitar lick that totally transformed it. I wasn’t mad about it.

Then there’s Aaron Sterling. He’s on records with John Mayer, Jason Mraz, Sabrina Carpenter, Dua Lipa – you name it. Watching him work is like watching a world-class athlete in the zone. He’s lightning-fast, but never overplays. His genius is in his restraint and intention. He hears the whole landscape, every genre, every nuance, and then gives the song exactly what it needs. His advice to me was simple but powerful: “Keep going! Don’t stop.”

That’s the spirit of Nashville – it’s where excellence, generosity, and grit all meet. I showed up hoping to make a great record. What I got was something far bigger: collaborators who challenged me, championed me, and helped me grow into the artist I’m becoming.

The string arrangement by Shaan Ramaprasad adds a cinematic quality. Can you talk about how that orchestral layer deepened the emotional resonance?

Jeeves: We were both intentional and intuitive with this arrangement. If you listen closely to the intro, you’ll hear violins and violas panned from left and right – like voices approaching from different directions. It’s subtle, but symbolic: those strings represent a conversation, multiple perspectives, or even fragments of memory pulling at the edges of the song.

The bridge is where the track takes a turn – it’s the emotional swell, the point of overwhelm – and the strings mark that shift with a sense of inevitability. When I sing, “but the waves keep crashing over me,” you’ll hear a synth and Shaan’s strings collide, just like two waves meeting in the ocean. That sonic clash was entirely intentional – it feels like being submerged.

But my favorite moment came from metaphor, not sheet music. Instead of dictating notes or software notation, I asked Shaan, “Can you end on a hopeful note? Can you create a spiraling staircase rising into the heavens?” And without missing a beat, he said, “I gotchu.” What he delivered was more than I could have imagined: interwoven arpeggios moving at staggered tempos, cascading upward, shimmering, climbing – an ascent toward something divine. It’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard.

When Shaan sends back a finished orchestral part, it feels like heaven arriving in a .wav file.

And here’s a bit of lore: Shaan is always early. We finished the string arrangement in 2023 – long before the rest of the production came together in 2024. It’s now July 2025, and somehow everything is right on time.

You performed the song at Hotel Café and recorded a jazz trio version in New York. What do those live settings reveal about the song that’s different from the studio recording?

Jeeves: A good song can be reinterpreted in a variety of contexts. I sang this solo while playing piano with a lit candle for friends and family. I’ve sung it with Joe’s trio, played it in LA with a full band, enjoyed it solo with an acoustic guitar, and am currently working on an a capella arrangement with a men’s octet.

When you’re recording, you have no idea who you are going to touch or affect or move, and you do so in isolation or with the company you keep. “]

Jeeves: When I played it live, I discovered our humanity. Most poignant is the pin-drop silence that suddenly finds room in our hyper-distracted modern era, and a respect that my audience pays towards me and the moment. Perhaps there’s a sixth sense when you know that an artist isn’t performing for applause or attention, but to speak their truth. Perhaps then, you know you have something special. What my heart wasn’t prepared for, however, but can now understand, is the mutual vulnerability that ensues. We all suffer, and there is a diversity of people who come and tell me their story, completely unrelated to anything I’ve ever experienced, and I feel my empathy for the world deepens more; I find myself holding more stories than my own, somehow stronger for it.

How do you balance jazz, soul, and singer-songwriter elements in your live sets? And do you prefer stripped-down performances or full-band arrangements?

Jeeves: I love the bold and maximalist vision as much as I love the honesty and rawness of an acoustic guitar. I used to perform at open mics quite often, starting out and there is a magic to a songwriter in a coffee shop. Never underestimate a singer with an acoustic guitar – songs are ideas that cross borders without a passport. There is an elegance in knowing how little it takes to achieve a maximal resonance with the world; an engineer might call that torque.

Your debut album, Now or Never, drops later this year. What’s the overarching narrative or emotional arc of the record?

Jeeves: What a great question! In an infinite universe of possibilities, choices collapse the field of probabilities of where we are and where we could be into a singular now. Time only marches forward and grabs us by the wrist. Life is marvelous, yet horrendously short. So what do you want? What do you wish to see and feel in your life? What if today were your last day? Memento mori, so they say? Now or Never is the ultimatum for the paradox of choice – an exploration of regret, how to live a life without them, and come truly alive.

I wrote a poem to pair with the album and introduce it, so I’ll share it for the first time here:

Months of boredom, moments of terror.

I don’t like who I am in the mirror.

And so I stared into my shame,

shame for staying the same,

so I vowed to change.

Packed my things, left my home,

said goodbye to everyone I know,

not waiting for an answer,

acting with the gift of pressure,

faith in virtues I have yet to discover,

courage a friend, dare I say a lover,

in my pocket, up my sleeve, closed my eyes and opened them to see,

God as my witness … it’s Now or Never.

What are some sonic or lyrical risks you took on the album that you’re particularly proud of?

Jeeves: By now, I hope it’s clear – I don’t write songs unless there’s risk involved. The world already has so much great music; if I’m not adding something new, what’s the point?

Sonically, this album is all over the map – literally and metaphorically. I introduced a mandolin into my sound just because I could. I wrote my first song in Spanish, Catalina, inspired by my Colombian brother-from-another-mother, Juanes. It’s fiery, unapologetic, and perfect for a wild night with tequila. There’s also a disco-inspired track, a nod to Quincy Jones, where I’ll probably need a sparkly suit and a few JT dance lessons.

Lyrically, I pushed myself to ask uncomfortable questions. In Waiting to Be Seen, I admit something I’m not proud of: “Do I love who you are, or do I see you as clay?” That line scares me – but that’s how I know it’s honest.

For Fractions of Your Love, I studied flamenco guitar and sang partly in French. But the real risk – the crown jewel – is Share a Kiss. That one took everything. We recorded takes late at night in London, tracked a 32-piece string section, did vocals in David Bowie’s producer’s studio, mixed with Sam Okell from Abbey Road (who added his Harry Potter magic), and sourced a vintage drawing of Royal Albert Hall from 1889 for the cover art. I even got a bespoke suit made by the tailor who dresses the Kingsman cast – because I played him the song and asked, “What do you see?” And he saw it.

All of this, to tell one girl I love her.

It’s a love letter, a time capsule, a dream – and yeah, maybe leaking it to the press is my way of manifesting the future. If this record becomes the thing that lets us tour the world together, then every risk was worth it. Life can change in an instant. It’s Now or Never – and what we create can last forever.

You’ve described your music as an invitation “to feel more, fear less, and come alive.” How do you hope this upcoming body of work helps listeners do that?

Jeeves: We live in an anxious world – one moving at breakneck speed, where politics divide, rights are stripped, and technology often disconnects more than it connects. In a time like this, even asking what it means to “come alive” feels radical. But that’s exactly why I choose to create.

Music is where I feel the heart of the world. And though much of today’s sound leans into “dark pop,” reflecting our collective uncertainty, I’m offering something different: an emotional arc rooted in growth, self-compassion, and joy. This record traces my own journey – from self-doubt, fear, and existential dread to stillness, love, heartbreak, healing, and eventually hope.

To quote Tolstoy, “art is a means of communion,” and Rumi, “Yesterday I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself.” That’s the spirit behind this work. My hope is that listeners hear that evolution – my transformation – and recognize pieces of themselves in it. That they feel less alone. That they reclaim joy. In today’s world, even that can be a quiet act of rebellion.

You’ve talked about music as a tool for healing. What role does catharsis play in your songwriting, especially on this track?

Jeeves: In Indian classical music, art is a form of devotion – a way to commune with the divine. I think my heritage carries that sensibility into everything I create, whether I intend it or not. Now that I’m formally studying Hindustani vocals, I’m stepping even closer to those roots, and it’s changing the way I write. There’s a spiritual undertone in the music I make – an acknowledgment that sound can move people, not just emotionally but energetically.

But I’ll be honest: some days, I don’t want to think about divinity or legacy or healing. Some days, I just want to be an American, grab a slice of New York pizza, and turn off the loop of my unresolved traumas playing in my head. And that’s part of the healing too – permission to just be.

Still, when I write from a place of catharsis, I’m awake to the power in it. I believe that suffering isn’t wasted when it’s alchemized into art. Songs like “Where Did All The Good Men Go?” come from a deeply raw place, but the act of sharing them transforms that pain into something communal. I think that’s the secret role of the artist: to metabolize the unspeakable and make it singable. Or, to quote Mission: Impossible, there’s always that whispered voice asking, “Should you choose to accept…”

So yes – healing is always the intention behind those more reflective songs. That’s my raison d’être: to heal myself, to heal the world. But also… can I just rock and roll now? I’ve got a pink electric guitar, my distortion pedal is dialed in, and I think I’m ready to have some fun.

Also – I could really use a cheeseburger and a glass of Barolo right now.

If someone discovers Jeeves through this single, what do you hope they walk away with about you, and about themselves?

Jeeves: If someone discovers me through this single, I hope they see my deepest wounds and fears laid bare – no shame, just honesty. It’s a brave choice to share your heart so openly. Trauma is universal, but healing means learning to transcend it, not carry it forever. With time – and maybe years – we grow beyond our scars. This song reveals a part of me, but there’s so much more to come. Most importantly, joy is on its way.

— —

Disclosure: The writer of this piece also serves as the artist’s publicist. All opinions are their own, and this feature was written with the intention of celebrating and supporting the music.

— —

:: stream/purchase Where Did All the Good Men Go? here ::

:: connect with Jeeves here ::

— —

“Where Did All the Good Men Go?” – Jeeves

— — — —

Connect to Jeeves on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Stef Martin

:: Stream Jeeves ::

© Stef Martin

© Stef Martin