In his hauntingly honest debut ‘Crowd Pleaser,’ alt-country singer/songwriter Joelton Mayfield lays bare grief, faith, friendship, and the fragile joy of starting over.

Stream: ‘Crowd Pleaser’ – Joelton Mayfield

There are debut albums, and then there are bodies of work that feel excavated rather than written.

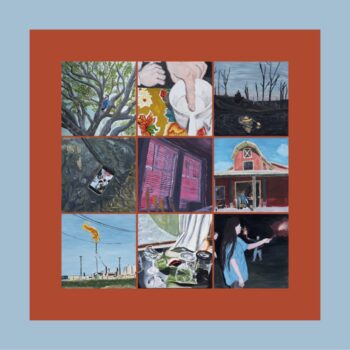

Crowd Pleaser, the long-awaited first full-length from Texan singer/songwriter Joelton Mayfield, belongs entirely to the latter. It is a record shaped by heartbreak, pandemic-era isolation, spiritual fracture, communal devotion, and the messy, unromantic labor of becoming a person again after your world blows apart. Mayfield entered the recording process at 23 with a handful of songs, $6,000 saved from service jobs, and the kind of naïve fearlessness that only comes from not yet knowing how much life can hurt. What he walked into was three intense weeks in a barn near Alabama’s Mobile Bay – surrounded by ten friends, stacks of area rugs, a vibraphone inherited from his grandmother, and the fresh open wound of a breakup that shadowed every take, every overdub, every breath.

That barn became a crucible. A pressure cooker. A sanctuary. A battlefield.

And the album that emerged from it doesn’t hide a single bruise.

Recorded mostly live in a time when vaccines were barely accessible and hope felt like something you had to squint to see, Crowd Pleaser captures what happens when a group of people decide, collectively, to hold someone upright through grief. The record thrums with that strange, electric tenderness – friends playing harder to lift the room, time signatures bending under emotional weight, pedal steel and vibraphone lines trembling with the effort of keeping someone from collapsing.

It’s not just an album; it’s evidence. A sonic document of love, loss, confusion, and the weird holiness of being witnessed at your lowest by the people who stay anyway.

Across its ten tracks, Mayfield wrestles with spiritual trauma, disillusionment, alienation, and the peculiar loneliness of coming of age inside systems that demand everything and give very little back.

Yet there’s a clarity in the chaos – moments of humor, grace, revelation, and raw self-interrogation that make Crowd Pleaser feel less like a debut and more like a reckoning. A decade in the making, four years in the healing, and a lifetime in its emotional reach, the album stands as a testament not just to songwriting, but to survival.

In this extensive, vulnerable conversation with Atwood Magazine, Joelton Mayfield walks us through the fracturing that shaped the record, the friends who held its seams together, the ghosts that still follow him, and the lessons he didn’t expect to learn. It is a rare, generous look behind the curtain – into the barn, the heartbreak, the pressure, and the music that ultimately carried him out the other side.

— —

:: stream/purchase Crowd Pleaser here ::

:: connect with Joelton Mayfield here ::

— —

A CONVERSATION WITH JOELTON MAYFIELD

Atwood Magazine: Crowd Pleaser has been a decade in the making, and it arrives with so much emotional and sonic weight. How does it feel to finally release it into the world?

Joelton Mayfield: It feels really, really good. I got more than I bargained for, in so many ways, with the recording process. This is my first album. I had no idea what I was doing. We recorded just before Covid vaccines were readily available. So, everyone got tested multiple times, isolated, and traveled to a barn in Alabama where we lived and recorded for three weeks. I was paying for all the expenses out of my savings and didn’t have support or representation at the time. I walked in with six thousand dollars and left with about ten bucks. I had also just turned 23 and thought I knew everything. So with the financial factor, not wanting to risk anyone’s health at my expense, and not really knowing what I was doing, it was pretty stressful and I was pretty lost. But on top of that, I was broken up with five days before we began recording by the only person I’ve ever really loved that much. This person was also involved in planning the album and was supposed to co-produce it, staying with the intention of doing so for the first half of the recording process. But it was nearly impossible for us to even be in the same room, so that didn’t really happen. I was miserable and it was a bad situation. So, I feel all of that in the recordings. The fracturing of that relationship really sent me down a dark path that I still haven’t totally recovered from. While recording, I was barely hanging on, doing horribly in a very apparent way. A couple of the folks who helped make the record have since told me that, early on in the recording process, they were trying so hard to just play their asses off, hoping that would turn my vibe and the air of the whole situation around and everything would be fine.

And there were moments of musical salvation for all of us, I’d like to think. I think you can, at least, hear that sentiment in the time changes and the volume swells performed in “Turpentine (You Know the One).” I think you can hear it in the tenderness of “Mouth Breather” and the noisy crescendos of “Red Beam.” I can, at minimum, feel the intensity. So, yes, it carries a lot of emotional and sonic weight. It feels great to finally be walking away from it. It was a lot to even begin to approach finishing the album after we left Alabama – not that we had more than a few BGVs, a woodwind, and an acoustic guitar or two to add. Just emotionally speaking, it was a lot to approach. I’m really glad and proud that we did finish it, though. I think there’s a very real world in which these recordings were still, to this day, untouched in my Dropbox. And yes, in the sense that it’s 2025 and I wrote (or began writing) some of the songs on the record as early as 2016, it has been nearly a decade in the making. But the album itself was recorded mostly live over those three weeks. If I could make this record all over again, I’d do most things differently. But I am grateful to have made an album at all, my very first one, and somewhat amazed and proud to feel, four years later, that I still stand behind the strength of the songs and the witness of the recordings. I hope that Crowd Pleaser can exist as a document of grand intentions; a testament to true friendship; one hell of a genesis to grief; and maybe a stupid joke about caring too much. I feel a tremendous sense of relief walking away from these recordings and releasing them.

The recording process took place in a barn near Alabama’s Mobile Bay – surrounded by friends, heartbreak, and rugs to soften the acoustics. Can you walk us through what those three weeks felt like on a personal and creative level?

Joelton Mayfield: I’ll try my best. The feelings are a bit blurry now, four years and a lot of therapy down the road, other than just general pain and moments of musical salvation. But the facts I know. Crowd Pleaser was recorded mostly live in a big, two-story barn on my friend Linda Parrott’s family farm in Fairhope, Alabama, between February 5 and February 28, 2021. The property has since been sold and the state of the barn is unknown. I cannot possibly thank Linda and her family enough – not only for providing such a perfect and wonderful space to record, but also for letting us live there and use the space and its amenities basically for free when I had no budget for a project of this breadth.

I drove two trailers full of instruments, recording equipment, and area rugs from Central Texas and Nashville, Tennessee, respectively, even bringing down a Hammond M3 and my grandmother’s vibraphone. I am very lucky that all of my friends were willing to commute from Nashville or Central Texas to contribute their talents, care, and time to making this album, even luckier to have ever known their love and friendship. The only way we were able to safely make a live record in February of 2021 was to get tested repeatedly, in advance, and isolate until results arrived from at least two tests. It also helped that just about everyone was unemployed or working remotely, and therefore available, at the time. I remember it feeling strange to spend a month with ten people in a barn after spending a year alone. It was hard to make eye contact. I was broken up with just before we began recording and the fallout of that relationship loomed large over the entire recording process and haunts corners of my life to this day. They had previously agreed to work on the album, staying with the intention of doing so for the first half of the recording process, but being in the same room became completely unbearable, and they also had a lot on their own plate. It was a really bad situation. I had just turned 23, it was the first time I was ever serious about someone, and I handled the breakup very immaturely. They also had very unrealistic and poorly communicated expectations of me and our mutual friends, many of which were there working on the album. It was completely uncareful and destructive. For me, and for many of my friends who helped make this album, all of that pain is in these recordings. If I could make it all over again, I’d do most things differently. But that’s what makes it a record, I guess, a document.

But creatively, from what I remember, I learned so much. It was my first time recording pretty much everything totally live, which I knew was something I wanted to do going into it. It was my first time doing group overdubs. In the barn, we set up a small live room upstairs, a large live room downstairs, and a control room off to the side. Most of the live, full band takes would happen downstairs. Then we’d overdub banjo, dobro, acoustic, and mandolin upstairs simultaneously while overdubbing organ, vibraphone, or pedal steel downstairs on top of the live take. So, you’d have five to six people doing the live take all together and then four to five people doing an overdub all together. It made it so that we all played to each other really well and there weren’t a ton of comps. We just ended up muting tracks here and there, section by section. It was very fulfilling creatively, when that was something I could focus on.

You describe this album as a “map of unraveling and reformation.” Were there specific songs that unlocked that shift for you?

Joelton Mayfield: I don’t recall saying that! Honestly, that may more accurately describe the next album; but when we were recording Crowd Pleaser, there was a real shift when we figured out “Speechwriter.” Initially, “Speechwriter” just sort of sounded like “The Reason,” from my EP, I Hope You Make It. If you imagine me just singing and playing “Speechwriter” on acoustic guitar, you can probably picture that. But we got rid of some of the chords and spiced it up a bit. When we play it at shows, we get pretty Motorik with it and go to crazy-town in guitar world. But for the recording, I remember us saying that it should exist on a spectrum between “Spiders (Kidsmoke)” by Wilco and “Honky Tonk Women” by the Rolling Stones, which I think is a pretty funny binary. So, figuring out “Speechwriter” was definitely a turning point in the recording process. There were a lot of times I considered just calling it quits, packing everything up, and leaving the barn. I think the creative discoveries we kept making, like we did with this one, kept me there.

There’s a powerful duality in “Speechwriter” – the disillusionment with systems of power and the raw question, “How can I convince you anything I’ve ever felt is worth grieving?” Was that line a starting point for the track, or did it emerge later in the writing?

Joelton Mayfield: I think that line gives “Speechwriter” its meaning. Without that line or that fourth verse, the song goes nowhere. The personal is the political. You are what you eat. It had to arrive there. So, I guess that wasn’t the starting point; it was actually the conclusion. To me, “Speechwriter” is a song about feeling lonely, alienated, and powerless, particularly when we’re misrepresented, unheard, and othered by the very forms and figures claiming to represent us – whether we’re talking your congressperson, your father, your prescribed gender role, your class status, all the above. That’s what the first three verses address. With the chorus, I was trying to emphasize that alienation is a shared experience. The world is full of people, yet loneliness is a popular feeling, which is a weird fact we’ve all come to live with. You’d think both things couldn’t, or at least shouldn’t, be true simultaneously. I think the mediating forces we’ve accepted under capitalism and patriarchy, often via the illusion of choice, are to blame. And not having leverage over your own sacred life is some bullshit. In the opening verses, I tried to have an oracle of sorts relay this message: the speechwriter, my father, and a girl I know. In the fourth and final verse, which has the “How can I convince you anything I’ve ever felt is worth grieving?” line, I tried to pit the hand I was dealt against the fates I can actually change. I can change my fate through willpower and hard work, sure, but also through luck and privilege. I don’t mean to chalk it all up to some Magic 8 Ball at the end of the universe, but I think clashing my own agency with the conditions of my own life is, in a word, helpful. Maybe there’s a lot I can’t change about the way things are outside and inside of me, but it is nevertheless possible to begin trying to, at minimum, disentangle some of the threads. The final chorus of “Speechwriter” acknowledges that thought.

You’ve been open about growing up in a deeply religious environment, later finding your way out of it. How does that journey continue to inform your writing?

Joelton Mayfield: In lyrics, I love a good Biblical reference as often as I can get one. I got first place at Junior Bible Quiz when I was in elementary school, so it’s all still in there. I’m a big fan of the Mountain Goats too, and I love John Darnielle’s consistent Biblical references and reworkings of scripture across his catalog. At this point in my life, Christianity is not a helpful framework for me at all. I’m religious about a lot of things, but I don’t fuck with Evangelism or the Christian church. I don’t need Christianity to have empathy; a lot of people, it seems, may. Believing Jesus died for your sins and truly loving other people are, like, the main things. But that does not even seem to be what American Christianity – the majority of which is completely absorbed into the MAGA deathcult now – is interested in. And it was probably never about that for most Americans, with the largest actors being Prosperity Gospel and CUFI pedalers. It seems to all be about what you’re at odds with, not even remotely being in line with, for example, being a good steward of the dying earth or loving thy neighbor.

I was agnostic too, for a time, and wanted to change the church from the inside. But for most of my time in the church, I witnessed the ways in which the scripture was weaponized. I also witnessed the ways in which the culture itself, devoid of any real Biblical basis, was just used to spread bigotry and reinforce white supremacy. So, I guess I just feel like if you’re part of it at all, you’re endorsing the Christian fascism thing going on. It’s not really an institution that can be changed and used for good – in my experience and in my opinion. I’m not an atheist either. It’s just not my framework. So, I don’t really wish to define myself by it. I would say that my Christian upbringing is still influencing my writing though, as much as anything literary would. It’s a foundational text for me. Also – at least across Crowd Pleaser, less so for what I’m writing currently – processing spiritual and religious trauma is a common theme.

You’ve cited Dylan, Sufjan Stevens, David Bazan, and Jeff Tweedy as influences – songwriters who explore faith, grief, and meaning with nuance. What drew you to that lineage?

Joelton Mayfield: I was raised on Southern Gospel and the CCM (Contemporary Christian Music) of the late ’90s and early ’00s. That’s what was always on the stereo in the house and the radio in the car. That’s what all the CDs were, alongside the Focus on the Family cassette tapes. My first concert that I remember attending was the Gaither Family Homecoming in Dallas, Texas, in 2004 or 2005. My parents do tell me I was at a Red Rocks show when I was six months old, but I don’t remember that for some reason. So, music about God – with a very sanitized, saccharine sound and a super cranked vocal – is all that was encouraged throughout my whole upbringing.

But my dad did have two Dwight Yoakam cassettes and Randy Travis’s Always & Forever alongside his Phillips, Craig and Dean tape. He’d bump those in the truck when he dragged me out of bed at 5 a.m. to go sit in a deer blind. My grandma, on the other hand, would almost always have classic country playing on her stereo when I’d go over to her house. So, I got introduced to some greats through her – George Jones, Dolly Parton, Bob Wills, Hank Williams, the list goes on – and I inherited a lot of her records when she passed. So, while it was pretty exclusively CCM and whitewashed Gospel growing up, country music was sort of the first alternative for me. And of course, at home and not at my grandma’s, people like Willie Nelson were also a presence in my Texan childhood, growing up thirty minutes from where he lives in Spicewood, but it was really only when he was on PBS for Austin City Limits.

Early high school, the local Christian radio station, 102.3 The River, transitioned to “Positive Alternative,” which is code for Still Christian in Vibe, so I started hearing The Fray, Lifehouse, Switchfoot, that one Faith Hill song, all those guys. But I also got obsessed with blues music during that time as well. We finally got Wi-Fi and internet service at my parent’s house. At our dirt-road home, the internet had previously only been available in dial up, which my parents didn’t have or want. So, I was going to the library for most of my homework until then. Anyway, I got obsessed with the blues – funnily enough, through going down a John Mayer live guitar solo rabbit hole on YouTube as a 13- or 14-year-old kid just beginning to take guitar lessons. Robert Johnson, Albert King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy – I did deep dives on most of them. Around that same time, I found a box of LPs, the only vinyl my parents had not gotten rid of, and stumbled across the Pat Garret and Billy The Kid (1973) soundtrack. Hearing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” changed my life. I’ve been obsessed with Bob Dylan ever since. I’ve seen him play five times in the last four years. Shortly after discovering the Pat Garret and Billy The Kid soundtrack, I started writing songs, when I was probably around 14 or 15 years old. Late high school and early college, I began actually seeking out my own music online – figuring out what I actually liked, what actually made a song moving and good.

My very dear friend, Lane, who I went to high school with and who played all over Crowd Pleaser, contributed a lot to the development of my music taste. She’s the reason I heard the music of Neutral Milk Hotel, Radiohead, Sufjan Stevens, Bjork, and so much more for the first time, around the end of high school. Then, in college, I heard Wilco, Pavement, Broken Social Scene, and other late ’90s and early ’00s rock bands for the first time. Most of that music was sent my way by Nick Johnston, my dear friend who also played all over the record. Yankee Hotel Foxtrot and A Ghost is Born is kind of where I found my first love for production and the way things sounded and moved. And artists like David Bazan and the Mountain Goats sort of scratched my post-Christian itch. I feel like I was slowly learning how to serve a song. In the middle of college, I got into heavier music. I started listening to a lot of post-punk, classic punk, and emo, even forming a heavyish, post-punky emoish band with Ben Thomas, Hunt Pennington, Linda Parrott, and Bennett Emery, all of whom played and sang all over Crowd Pleaser except Bennett, who played drums on my EP, I Hope You Make It.

The album title, Crowd Pleaser, feels delightfully ironic given how intimate and self-exposing the songs are. What does the title mean to you?

Joelton Mayfield: The last song on the record provided the album title, the titular line being: “I’m a mouth breather / I’m a crowd pleaser / you’re a believer in things unseen.” “Mouth Breather,” the title of the song that these lyrics come from, is about trying really hard to be the best version of myself, hoping the person who beheld me would love me for trying, whether or not I succeeded. And this album, Crowd Pleaser, is my very first album. I felt like I was auditioning for love in the relationship “Mouth Breather” was written about. With this being my debut album, it also feels as though I’m auditioning for the career I hope to have as an artist and songwriter. Personally, that’s why Crowd Pleaser felt like the most tonally appropriate title on my shortlist.

Additionally, six of the ten songs that comprise Crowd Pleaser are songs that I’ve been playing live for a long time, songs that I wrote over the course of five years. And, in that way, the record is sort of a mixtape. In other words, half of the recordings are favorite songs from live shows I played between 2018 and 2020 – a compilation of “crowd pleasers,” if you will. They are the best songs I wrote in my late college, early postgrad life, the songs that stuck around. While there are many common threads and repeated lines across the LP, the majority of the songs had their own separate lives first before I started sewing them together at the seams.

One of the most poignant tracks, “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase,” feels like a hymn for those deserted by faith. How did that track come together, both lyrically and musically?

Joelton Mayfield: To me, “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase” is a song about pocket providence – playing the god card to justify any number of horrific things. To a lot of listeners, that does not appear to translate or be overt enough. So, thanks for picking up on that! At shows, I’ve had a number of Christians at the merch table – including people in my own family – tell me how moved they were to hear “a song about Jesus,” ask me what my relationship is like with their god, or any number of things. But that’s okay. The listener ought to have their response. It’s all up to interpretation, like the Bible! That being said, I’ve had people who were hurt by the church open up to me at the merch table. They tell me they were moved by the song and then we have a conversation about spiritual and religious trauma. So, in that way, it’s been awesome to make a deep connection with other people because of something I made. I wrote the opening verse of “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase” in 2018 during my first semester of American literature. I was, obviously, thinking about manifest destiny a lot. I then began seeing parallels to this idea throughout history – that god would “give” his alleged people a land already inhabited by Indigenous people.

To over-explain: In the Bible, Jacob is travelling alone across a foreign land, goes to sleep in a pasture and uses a rock as a pillow, and has a dream that there’s a ladder extending into heaven where god, from above the ladder, promises him the land he’s sleeping on. Jacob wakes up and renames the land Bethel, meaning “house of god.” Joseph, the “human father” of Jesus, is Jacob’s son. So, this story is pretty essential to the core of the Bible and Christianity.

Though colonizers mostly used god’s deal with Abraham as justification for genociding Indigenous people in the United States, the story of Jacob’s ladder follows an eerily similar line of thought. In “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase,” I have Jacob dream that he can have whatever he wants. I have Joseph, the second generation, dreaming just “like his father before him,” but with a new pocket providence that sounds a lot like gentrification. So, god can be whatever you dream, which is probably how I would describe the choruses.

When I was unemployed and holed up in my house in 2020, I got a lot of writing done. I came back across the opening verse and it was immediately apparent to me that I should write vignettes about biblical characters who were “given something by god” that directly put someone else out or to death. Rahab, the sex worker who’s Joshua’s confidential informant, came to mind. There are some verses that I abandoned as well, but it felt most appropriate to root the song in a middle-class imagined father-son relationship present day, paralleling Jacob and Joseph. I would say the fourth verse recognizes that the promise of the American dream haunts deep and ultimately leaves its dreamers disillusioned. I had just finished reading The Protestant Work Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism at the time, so I probably owe the posture of the fourth verse to that. Musically, “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase” was quite the journey. I had written all these minor key or pentatonic scale chords into the song. I had a vision of a full-band version that was sort of in the style of the band Bread, but ultimately – about halfway through the recording process – we realized we didn’t really have any recordings shaping up to sound like a song might have sounded when I first wrote it. So, I performed “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase” during a night-time rainstorm, just as I wrote it, guitar and vocal. In the recording, you can hear the rain, faintly, on the tin roof of the barn where we made the album. I did one and a half takes before my alarm went off for my psychotherapy appointment and we had it in there. Two guitars, Omnichord, background vocals, and one pedal steel moment were overdubbed in the following days.

You open the album with “Red Beam,” which you’ve described as “a theme song for stumbling into the unknown.” Why did that track feel like the right introduction to this body of work?

Joelton Mayfield: I believe someone else might have written that description on my behalf! I would actually revise that to describe “Red Beam” as an apocalyptic dirge attempting to make peace with spiritual and religious traumas still engrained in the way I react to the beautiful and horrific world we’ve inherited. And if peace can’t be made with the trauma, it is at least a good, long wallow in the anxiety and depression informing my way of being. “Red Beam” leads into “The Shore” too, which is in many ways a song about love at the end of history.

I think “Red Beam” was only ever going to be the opener. It’s a song I wrote on guitar – with a more folky, Freewheelin’-esque sound – but when I took it to my band, I started playing it on piano and it just made sense for it to drone along and crescendo into chaos. That was, at least, my idea for the arrangement. Sonically, it makes the most sense as the opener. It’s maybe the most intense song on the album. It drops you into the lyrical world too, introducing lines and turns-of-phrase that are repeated across the album. I suppose it could have also been the closing song, but the narrator’s emotions are parsed out over a panic attack at sunrise and sunrise is when things begin.

There’s a deep musical intelligence in how you fuse alt-country tradition with experimental noise, drone, and non-linear structures. Did that sound evolve naturally – or were you intentionally pushing against genre expectations?

Joelton Mayfield: I appreciate that! I always want to serve the song. I’m almost always writing the words first and almost always piecing them together on an acoustic guitar or piano second. So, I guess I think my main job is songwriting. And I guess it does usually start with your standard folk song tools. But I also want to hold my own attention when I’m listening back and not focusing on the words at all. So, that complication of form usually gets done in the demoing and experimenting stage of arranging. And in that sense, it’s intentional. However, there are some songs I write where I’m already running out of the box with a non-trad idea. Such is the case with “Red Beam,” a song that arrived from a pretty anxious place. It just made sense to match the sonic landscape to the emotional landscape of the song. Having it drone along in swells to a crescendo of chaos is exactly the initial arrangement I wanted when I first brought the song to my band. I always wanted it to feel pretty explosive, anxiety-inducing, and dirge-like.

It was during the group overdubbing process that it began to make sense to interrupt the droning with the sonic “jump scares” in the recording. So, “Red Beam” is a song where the noise elements and the droning evolved naturally. I realize that the music I make lives under the Americana banner and most frequently (and appropriately) gets called alt-country. And that’s mostly because of the way I sing and my fixation on steel guitar. But I’m a fan of nearly all song-based music. I’m inspired by a lot of different kinds of music and I listen to a lot of music. I’m a nerd about it. I’m almost never thinking about genre when I’m solving for the arrangement and production of a song I’ve written. Granted, there are a couple of my songs where I’ve communicated to my band that I want to do a Krauty, Motorik thing. There have also been times where I’ve put together a bluegrass band. And there have been times where I’ve said, “I want this to sound like a Neil Young song, specifically (fill-in-the-blank) album.” But generally speaking, subverting expectations and sampling different sauces is necessary to me, as the first listener, to make a song that not only holds my attention but that I want to hear again.

Touring with your heroes, such as John Darnielle and John Moreland, is such a full-circle moment. What did you take away from those experiences, both onstage and off?

Joelton Mayfield: I was really nervous the first night we opened for the Mountain Goats. I’ve been a fan for a very long time. Right before we went on, John Darnielle walked into our green room and said, “Hi, I’m John, the singer from the Mountain Goats. Just wanted to say hello and thank you for playing these shows with us. We have fun.” I kind of blacked out, totally starstruck. I don’t really know what I said back to him. But by night two, I was a lot less nervous. It was really kind of him to do that. Everyone in the Mountain Goats and their touring party is extremely kind. You start to realize that your heroes are people. So, being around them is disarming. It may be obvious to say, but the relationship you have with their creative work is really where all your love lies. So, you just get to be grateful they made something that you found helpful or healing or whatever kind of way it hit you when it did. And John Moreland is a legend. I love his songwriting. It was a gift to open those shows for him last year. His fan base is so attentive and thoughtful. Everyone who met me at the merch booth had such specific compliments. It’s evident that John and his music have fostered a really thoughtful and tuned-in community. He is also a really kind man. He and Pearl showed up to my last two headlining shows in Tulsa where he lives. They came out early, stayed late, and bought me a round. You never expect that from somebody you open for. It was really heartwarming. It’s genuine care. And they’re such great folks to hang out with.

Opening for the Mountain Goats and for John Moreland happened a few months after I opened one show for Robert Earl Keen, which was the first time in my life I had the realization that I was actually a real performing songwriter. You know? Being a songwriter could be my job, or that was the first time I had that thought. You play every show you get asked to and you don’t really look up. And that week I opened for Robert Earl Keen was crazy. You have the artists you love and then you have the artists that your parents know. That was really the first time I could be like, “Look, mom. I’m doing it.” Not that she’s ever been unsupportive. She’s very supportive. But I’m from Texas. Robert Earl Keen is royalty there. The day of the show, I was pretty buttoned up, but after our set, I broke down crying in the parking lot. I guess that was the first moment where I felt like “this whole music thing” could work out, ten years into doing it. I had a really similar wow-moment opening for Steve Earle this summer. Touring is my favorite thing and I still can’t believe, over the last couple years, I’m getting to open for my heroes.

You’re part of a new generation of songwriters redefining what Americana and indie folk can be. What do you hope Crowd Pleaser contributes to that evolution?

Joelton Mayfield: The most loved music in my library and collection has healed, helped, and/or made me feel more understood and less alone. My greatest hope for Crowd Pleaser is that it makes somebody feel any of that. Otherwise, my contributions to subgenres of roots music are up to the beholders! So, thank you for listening and I hope we can all continue to serve our songs and get weirder and more interesting! I don’t really feel tied to much, but I’m zoomed all the way in on my own work. I do feel very grateful to be in the community I’m in, surrounded by the musicians, writers, and visual artists that I am. We’re weirdos and we’ve got a good thing going on. It’s hard to locate much hope in the world, with the ongoing genocide and dehumanization of Palestinians, the disappearing of people by ICE, and the global rise of fascism. Like, when is the last time anything remotely good happened? Community and art can help with that. Organizing and mutual aid can help with that. Music helps the world go ’round. My music can be whatever anybody who hears it wants from it. I made it because I had to and we made it sound the way it does because that’s what served it best.

You return to the line “God’s children never grow up” across the album. What does that refrain mean to you now, on the other side of making the record?

Joelton Mayfield: It depends on how you look at it, which was my intention with repeating the lyric, across the album, in different angles and contexts. On the one hand, “god’s children never grow up,” is a hopeful, empathetic, and grace-giving sentiment. It’s a way of saying that we’re never done learning. The lyric assumes that if any cosmic authority is to judge us, then they would certainly have to admit that many of us did our best. “Red Beam” and “Blame,” both songs that repeat the lyric, hang the sentiment in this positive frame. On the other hand, the lyric can be interpreted as a damning and angry indictment. It’s a way of saying that god’s children are living in a bubbled and babied state, disengaged with the world around them – unserious people who ought to check in and do some growing up. When the lyric lands in the song “Jacob Dreamed a Staircase,” I see the line more from this negative interpretation. So, on the other side of making the record, it’s an awesome line to sing because it means whatever I want it to at any given time. It can match however I’m feeling that night.

I once heard Gillian Welch say something like “The best songs are about pinnacle moments, moments of decision or revelation,” which changed how I thought about rooting my writing in time and how I thought about drawing conclusions. Across her catalog, she has the lyrics: “One more dollar and I’m going home,” and “Hard times ain’t gonna rule my mind no more.” That first lyric is an example of a decisive moment and that second lyric is an example of a revelatory moment. Having the narrator of your song realize something or decide something in an “and then” or “anymore” action – as your hook or your moment – is almost always moving and impactful, shored by the context of the rest of your song. Springsteen does this all the time: “It’s a town full of losers and I’m pulling out of here to win” being one example. I had just never heard it explained so obviously and plainly as Welch put it. With the lyric “god’s children never grow up,” repeated again and again, I aim to have it be a pinnacle moment of revelation across the record, across lenses and contexts, the word “never” grounding it in time – so that whichever light you see it through, the fact doesn’t change.

You’ve poured a lot of pain and reflection into this debut. What’s something you learned about yourself through the making of Crowd Pleaser?

Joelton Mayfield: I learned not to think that I know things. I thought I had the world totally figured out when we were planning to record this album. I was 22 and I had turned 23 a couple weeks before we began recording. I hadn’t really experienced that much yet, but I was quite the hardass about everything I thought and felt. I was willing to die on just about every hill. I’m not willing to die on most hills now, except for the few that matter. I learned that, no matter how well you know someone or how close you get to them, there will be a day when you never see them again. Didn’t really know that, from experience, going into this record. I do now. I’m more cautious, but also my daily interactions hold a lot less weight, which is a way of saying I’m more careful but I care a lot less. I’ve got to live with myself alone forever, which is to say I had to learn to love myself in a real way.

I’ve changed a lot. I’m older, slightly smarter, somewhat dumber, but still trying to kick a lot of the same habits and unlearn a lot of the same traits. I don’t want to be as precious and particular. I want to be less of a perfectionist. Reassurance is a trap and you can never get enough of it to convince yourself that you’re okay. You just have to pretend you are until you kind of are.

And finally, what’s next? After a record like this, do you already know what chapter comes after this one?

Joelton Mayfield: I’m ready to make the next record! I’m hoping to have a mostly positive experience this time. The bar is, unfortunately, not that high. I’m in the planning stages right now and will be doing a lot of demoing this winter. Most of the songs are written. It’s just a matter of deciding what sticks. I also want to tour as much as possible and I’ve got a lot of production work to wrap up before the new year. Basically, I’m looking forward to working more creative works out into the world because art helps!

* * *

Crowd Pleaser may have been born from chaos and collapse, but Joelton Mayfield emerges from it not just as a songwriter, but as a witness.

A witness to his own undoing and rebuilding. A witness to the power of community, of sonic experimentation, of banjos and pedal steel and noise and silence. This isn’t just a debut – it’s a warning shot and a welcome mat rolled out at once.

And while Mayfield is already eyeing the next chapter, Crowd Pleaser will remain a haunting, beautiful reminder of what it means to love deeply, lose recklessly, and still find music worth singing into the dark.

— —

:: stream/purchase Crowd Pleaser here ::

:: connect with Joelton Mayfield here ::

— —

Stream: “Blame” – Joelton Mayfield

— — — —

Connect to Joelton Mayfield on

Facebook, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Hunt Pennington

:: Stream Joelton Mayfield ::

© Hunt Pennington

© Hunt Pennington