I grew up without an older sister, but in the silver threads of Taylor Swift’s songs, I found a companion, a confidant, and a quiet guide through the labyrinth of growing up.

Stream: “Style” – Taylor Swift

When I felt lonely in my adolescence, I would put on a Taylor Swift CD for company.

I am the eldest daughter and the oldest child of four, so I never had an older sibling to rely on. No one to explain heartbreak, no one to give me quiet advice at the dinner table, no one to share the excitement of a first crush or first heartbreak. For some young girls, the role is filled by a favorite teacher, a fictional character, or a whispered diary entry. For me, it was a blonde teenager with a guitar and a spiral-bound notebook, whose voice rang through the CD player of my bedroom long before I knew how to articulate loneliness. I grew up as the eldest daughter of four, responsible, self-reliant, and too early acquainted with the expectation of being “fine.” Taylor Swift filled that void. She was the one who kept me company in the quiet spaces between homework and heartache. And she has never truly left. Her songs became more than music; they became confidants, mentors, and mirrors for the person I was becoming.

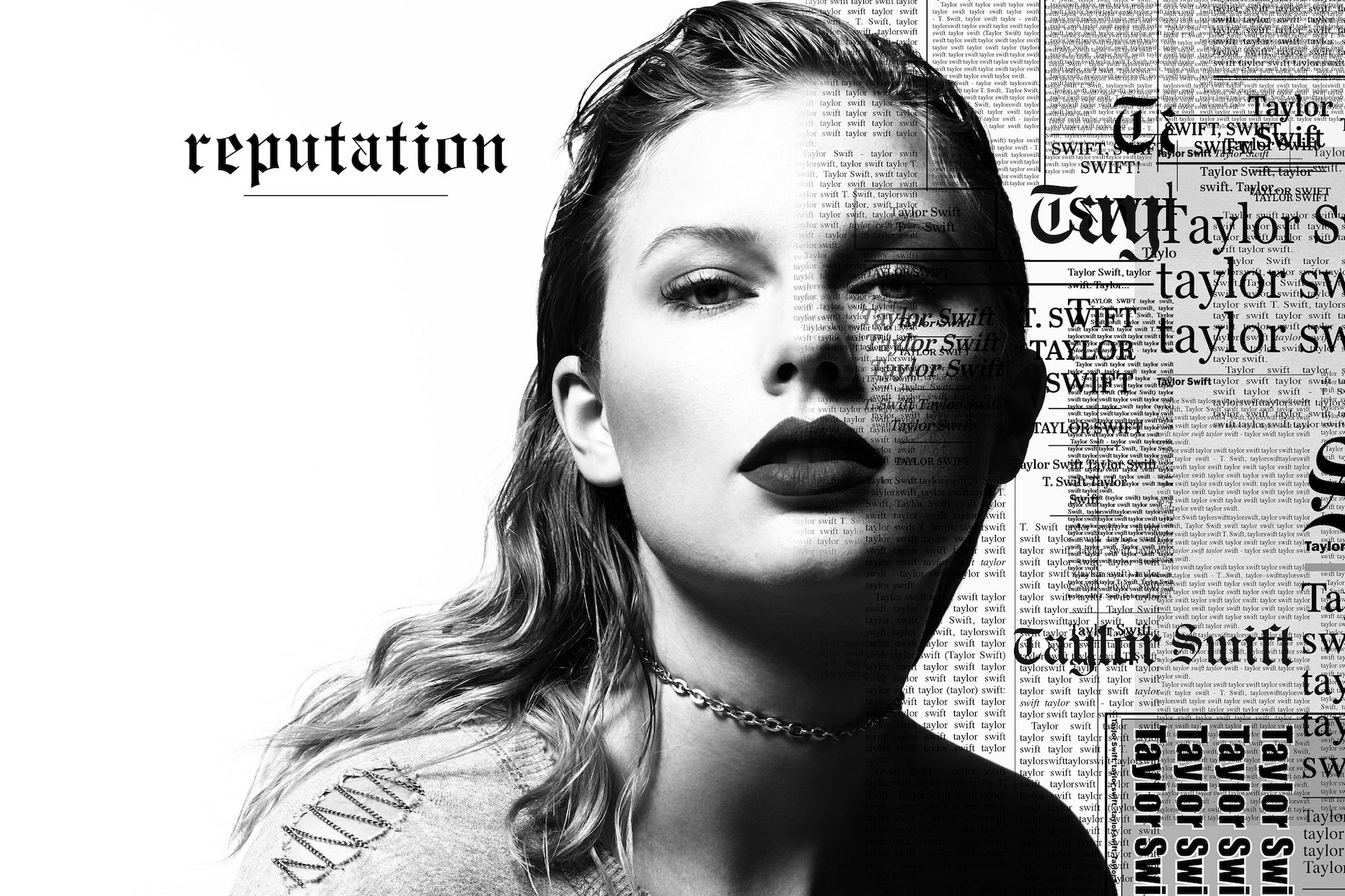

There is a peculiar intimacy in her songwriting, one that spans genres, decades, and personal growth. Swift’s catalogue is not merely a discography; it is a life map. And so much of my life can be measured against her albums as each record is a timestamp, capturing the joys, anxities, heartbreaks, and triumphs of growing up. Taylor Swift (2006), bought for me by my father, a gift I didn’t yet realize would change my life; Fearless (2008), the sound of teenage hope before the world complicates it, covered in glitter-pen daydreams, giving me optimism and fairy-tale hope; the early bruises of Speak Now (2010) inspired me to write, even as I navigated the uncertainties of adolescence; Red (2012) was heartbreak in technicolor I hadn’t needed yet, but knew someday I would; the shaky courage of 1989 (2014) was the thrill of reinvention released during my final year of school showcasing the glittering horizon of adulthood; Reputation (2017) was loud, brash, yet fiercely vulnerable; Lover (2019) gave me courage to publish my own poetry collections; Folklore and Evermore (2020) defined the isolation of COVID-19; Midnights (2024) captured late-night introspection and self-portraiture in synth and bruised reflection; and The Tortured Poets Department (2025) became a cultural and commercial milestone, cementing her status as a master storyteller. These are catalogues not just of changing sonic eras, but of changing selves.

And as I grew up, so did she, though her evolution was watched by millions, examined in real time, picked apart like scripture by critics who, somehow, always seemed to have a different rulebook for young women than they did for young men. Swift has built a career on the assumption, radical in an industry that historically privileges male narratives, that the interior world of young women is not trivial.

Yet Swift’s journey has not been without resistance. Female pop singers are subjected to a scrutiny their male counterparts rarely experience.

The themes Swift explored in “Dear John” or “Back to December,” love, loss, and introspection, were dissected publicly, reduced to punchlines on award shows and tabloid gossip. Male artists can write albums full of romantic lamentations or sexual self-mythologizing without anybody calling them “confessional,” “dramatic,” or, God forbid, “a pick-me,” but regularly framed as storytellers, poets, and craftsmen. Drake releases a lukewarm project, and the discourse revolves around production, rhythm, and bars. Swift releases an album, and within hours, social media has decided not only whether the music passes muster, but whether she does. Her personality. Her romantic history. Her worth. She has frequently been dismissed as confessional, immature, or overly diaristic.

A woman writes about her life, and it becomes an invitation for others to rewrite it for her.

Swift saw this treatment coming long before she learned to publicly fight it. In her early days, she was positioned as America’s polite media darling, fresh-faced, grateful, earnest. A “nice girl.” A “good girl.” A “safe girl.” But safe can cage.

This is not new. What is new is that Swift’s work has made this bias visible to a mainstream audience by virtue of scale. Every album release triggers a discourse cycle that reveals the fault lines of contemporary music criticism: Debates that begin in aesthetic evaluation often slide rapidly into evaluations of her personality, dating history, or public comportment, forms of scrutiny rarely applied to male peers. Swift does not need protection, but the discourse surrounding her work reveals something about who the industry considers deserving of legitimacy.

This resistance only sharpened her resolve. Taylor Swift has consistently rewritten the rules of the music industry, from shifting genres, country, pop, folk, rock, indie, and alt-pop, to reclaiming her masters through the Taylor’s Version project. Her advocacy for artist rights has forced a conversation about ownership, equity, and creative autonomy in an industry notoriously hostile to women. She has used her visibility not only to defend her own work but to expose structural inequities, all while maintaining the intimacy of her art.

The Eras Tour exemplifies this duality. For over three hours each night, Swift delivered a live anthology of her 17-year career, spanning ten albums and multiple genres. The production was cinematic, the choreography meticulous, yet the emotional core remained unvarnished. Fans like me were reminded that the music is never secondary; it is the connective tissue between performer and audience. Swift’s songs, whether about first love, heartbreak, or self-discovery, have provided guidance, companionship, and a sense of belonging.

For me, her music has always been a surrogate sister, someone who understood when nobody else could.

Her lyrics were my confidant; her melodies were my comfort. When Lover dropped in 2019, I felt an alignment I had never experienced before. Her anxious honesty about love, her grappling with confidence and self-perception, mirrored my own uncertainties in love and life. When Folklore and Evermore arrived during the pandemic, they were a lifeline, her imagined narratives offering an escape, her musical intimacy reminding me that even in isolation, I was not alone.

Critics have long attempted to dismiss Swift as overly confessional or calculated, but the truth is far more nuanced. Each album is a negotiation between personal truth and cultural performance, a balancing act in a male-dominated industry that often seeks to undermine women who are prolific and visible. Her capacity to remain authentic while navigating fame, scrutiny, and expectation is a testament to her resilience and to her artistry.

Prior to this, Swift’s trajectory is not simply one of artistic reinvention, it is the story of a woman who first learned the rules of the industry, then weaponized them, and finally rewrote them in her own hand. She began in Nashville, playing the country game the way the country establishment expected: Autobiographical songs, big choruses, the image of a teenage prodigy with shining curls and even brighter promise.

But even then, the seeds of something more ambitious were already germinating. She once said she begins writing by identifying the emotion first, story and melody follow like obedient children. That simple formula belies a craft steeped in complexity: The quill lyrics of poetic antiquity, the fountain-pen cinema of modern storytelling, and the glitter-pen spark of lived girlhood. In a genre dominated by men, she centered the feelings of teen girls, and critics, predictably, dismissed the subject matter as trivial because it did not mirror their own lives.

Still, she continued.

She pivoted from country to pop with Red, unsure of the ground beneath her feet, then claimed the terrain outright with 1989, an album so well-constructed and critically embraced that it forced even her doubters to acknowledge that she wasn’t just playing the pop game, she was reshaping it. Then came Reputation, the album that didn’t seek approval, didn’t apologize, didn’t soften its edges. It was the sound of a woman who had been burned publicly and decided to walk back through the flames anyway.

After that came Lover. Softer. Warmer. More exposed. An album she finally owned the rights to after years of industry machinations that revealed just how punishing the music business can be, especially to women who dare to accumulate too much power. Lover reminded listeners what she had always been beneath the fame: A woman in a New York apartment, guitar in hand, writing about love the way some people breathe.

From the fictional folklore trysts of Evermore to the nocturnal reflection of Midnights, to the blistered and cinematic heartbreak of The Tortured Poets Department, her music is both confessional and universal, diary and field guide. There is a song for every version of myself I have ever been.

Few modern artists possess a catalogue that stretches as widely as Swift’s: Country, pop, folk, indie, rock, touching R&B, alternative, and contemporary soundscapes along the way.

What distinguishes Swift’s evolution is not merely thematic growth but an increasingly sophisticated command of form. From the fairytale optimism of Fearless to the wistful retrospection of 1989, from the declarative October skies of Red to the fictional interiority of folklore and evermore, Swift has consistently demonstrated a willingness to mutate stylistically, not in pursuit of trend, but in pursuit of storytelling that matches emotional state.

Every era was not just a chapter in her story, but in mine.

Like many women in the music industry, like many women in any industry, Swift has had to carve space where she was never intended to stand comfortably.

She has been mocked for dating, mocked for writing about dating, mocked for caring too much, mocked for succeeding too much. She has been told she is overexposed, then criticized when she retreats. Too childish, too calculated, too sexual, too emotional, too loud, too quiet, whatever the world needed her to be wrong about.

Yet she pushed for artist ownership when few peers publicly supported her. She faced a machine much larger than herself and forced it to change anyway. Not just for her, but for the artists who would come after.

This is the thing about women like Swift: They do not simply survive the system; they expose it.

Swift’s longevity is not an accident. It is not merely the result of good marketing, smart branding, or lucky timing. It is owed to the living intimacy of her craft: She writes like someone who believes songs can save you, at least long enough to get you through the night. She writes with the awareness that feelings, even young ones, even girlish ones, are not frivolous. They are the foundations of being human.

Sometimes, when one of her albums drops, the internet erupts in contradiction: It’s genius, it’s disposable, it’s too pop, it’s too political, it’s not political enough. That noise has always surrounded her, but when the crowd disperses, when the stage is dismantled, when the lights go down and there is no audience left to please, what remains is this:

She is a woman with a guitar. She has a story she needs to tell. And millions of people, especially young women, have found parts of themselves through her voice.

I never had someone a few years ahead of me warning me which roads were sharp and which were glittering.

I found that guidance in the hands that wrote songs during high school lunch breaks, on tour buses, in hotel bathtubs, and in silent rooms at 3 a.m. Taylor Swift wasn’t my first idol. She was my first anchor. The older I get, the more poetic it feels to be alive the same time as Taylor Swift; we are two women growing up, not knowing each other, yet tied together in the way music sometimes makes us family.

Taylor Swift used to play it safe. Then she learned the game. Now she authors her own rulebook. And for the girls who grew up with her in our bedrooms, our school buses, our headphones, she taught us something invaluable: If the world won’t carve a space for you, you sharpen your pen and carve it yourself.

— —

:: read more Taylor Swift here ::

— —

— — — —

Connect with Taylor Swift on

Facebook, 𝕏, Instagram, TikTok

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Mert Alas & Marcus Piggott

:: Stream Taylor Swift ::

© Mert Alas & Marcus Piggott

© Mert Alas & Marcus Piggott