Atwood Magazine talked to Canadian artist Hanorah about music as a form of healing, finding the good and bad inside each of us, the return of Saturn, and her debut EP For the Good Guys and the Bad Guys.

— —

Hanorah is one of those artists whose presence you feel before she even steps onstage. There’s something about her: call it star power, good energy, or whatever you like, but she’s one of those people who steals your attention in the best way. Once she’s taken her place on the stage, she’s irresistible. Every word she sings she does so earnestly, it’s arresting and powerful. It’s a voice with meaning behind it, a purpose that overwhelms and overshadows anything but that moment: the stage is hers, and you want to hear everything she has to say.

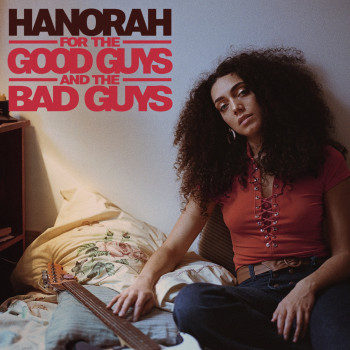

Lizzie Hanley started writing music and became Hanorah in search of healing in the aftermath of being sexually assaulted. Music became her way to process trauma and work through PTSD – and after she put herself back together, music became a conduit to spread her message of support and use her voice to help other survivors, as well as her preferred mode to work through feelings of everyday life. Hanorah’s debut EP, For the Good Guys and the Bad Guys, is a funky, soulful, R&B triumph.

Atwood Magazine talked to Hanorah about music as a form of healing, finding the good and bad inside each of us, the return of Saturn, and her debut EP For the Good Guys and the Bad Guys.

Listen: For the Good Guys and the Bad Guys EP – Hanorah

:: A Conversation with Hanorah ::

Atwood Magazine: Hey! So I saw you perform in Philly at the end of your US tour, but you‘ve been quite busy in Canada since you‘ve been back.

Hanorah: Yeah, it’s been a lot. The whole summer and fall has kind of been like that, since the record came out. A lot of good stuff, so I’m happy.

What shows have you played?

Hanorah: Most recently, I played a festival out here in Montreal called Pop Montreal, which is kind of a pretty big deal especially for emerging talent. And they had me on a bill with Mavis Staples, which was completely insane. She’s like, she’s been playing music for 70 years, you know, that was mind blowing. So that was at a place called the Rialto Theatre in Montreal, a really nice, beautiful, classic-looking theatre with art on like painting right on the walls and stuff. It’s really lovely. Really beautiful audience too. I was just really blown away by that show. And I did a couple of smaller things here and there as well, since I’ve been back going to do some more touring around Quebec in October, but then in November, I’m going to go to a town called Banff in Alberta, to do some songwriting with my co-writer, Paul.

Do you always go to a retreat to write?

Hanorah: This is actually the first time I’m ever going to do that. Normally, it’s just kinda been, you know, between rehearsals and shows or when there’s been downtime, I’ll pick up a guitar or I’ll meet with Paul, who’s my guitarist and co-writer, and also my boyfriend, we live together. Sometimes he’ll be like, ‘Oh, hey, I have these chords, do you want to, you know, sing on this, or want to write some vocal parts to that?’. And then sometimes I’ll have like, some chords or a vocal part, and then we’ll build it together. But this is the first time we’re actually going to get to go to a retreat and like, you know, attend workshops and stuff. And I’m really excited for that. It’ll be really cool.

For the Good Guys and the Bad Guys is your first ‘official‘ release, but you‘d released another EP before that. I‘m wondering how you‘ve changed between Post Romantic Stress Disorder and your latest project?

Hanorah: Yeah, I mean, the main difference, I’d say there are two main differences. One is that when I recorded Post Romantic, I didn’t have a band yet. And I couldn’t play any instruments yet. So I was kind of relying on producers and the odd musician here and there to kind of add, like a horn or a guitar part here and there. But what I was doing up to that point, because I didn’t really know anyone that was playing music and that I thought would want to work with me at the time, I was finding like beat makers on the internet and like buying tracks from them, or like meeting local producers and building tracks from scratch with them. So for example, the old version of “Clementine” was a British guy called JXXBX who kind of produces these low down hip hop tracks, and they’re beautiful. They’re really lovely, and easy for me to write to, probably because there’s like a mix of like vocal influences that I have. And this guy probably has similar influences in his music as well. So when I feel like a creative block, those tracks are usually really simple, just like rhythm focused. And it’s a lot easier for me to get a flow out from that. And also, like just in the lyrical content, at the time, I was still in a place of a lot more anger and bitterness and frustration, because I started writing music, to deal with PTSD, that resulted from a sexual assault that I experienced when I was 18 years old, I’m 25 now. So those first songs were really sort of angry and obscure, and had had a lot of like, negative – I didn’t want to be hurtful or anything, but I was working through a lot of really difficult things without a roadmap, really, so music was kind of the way for me to get those weird thoughts out of my head, like without frightening people, like music made things more palatable, if that makes sense. And now I feel like when I write songs, like, again, that happened seven years ago, and some of those songs I wrote as long as five, four or five years ago, so I’m just in a different place now, so I feel like there’s more love and more gratitude and more understanding of complexities of difficult situations, rather than just the ways it’s difficult. There’s also a lot of beautiful things that can come about a really hard time. So I feel like maybe just having gone down that process of healing for an additional five years, I have a much different perspective on life and that’s coming through in my writing.

You said that you started writing music to work through the PTSD. Had you never written songs before?

Hanorah: I’d written like, maybe one or two, before the assault when I was maybe 16, or something like that, 17. And, like a couple of really silly, more like jingles when I was like, nine or 10, or something like that. But yeah, I wasn’t playing music or writing consistently or playing shows until after that, until I was maybe 21. Those first couple of years after the fact were really difficult, obviously, and disorienting. And at the time, I was an art student, so I was sort of hiding behind painting to sort of like, not deal with reality, I guess. But then it came to a point when every day, I would wake up with like this feeling of dread and doom in my heart, and I was just so angry and bitter and it was coming out in school and at work and all my relationships. And I just decided one day that I didn’t want to live the rest of my life like that, that was what was done to me wasn’t my choice and I shouldn’t have to carry the weight of it, the way that I was, for the rest of my life. So what I did really simply was I took a piece of paper, and wrote down a list of all the areas in my life, all the things that weren’t working – so like, in school, with my jobs, with my boyfriend at the time, we’re not together anymore, friendships, my home, like with money, all everything. And just very matter-of-factly, one at a time, just kind of tackled each one as if it was just like a cleaning list or something. So like, I had to end a lot of friendships, obviously. I broke up with my boyfriend at the time, because he had this thing of like, I just decided that I wanted to play music, and that I had something important to say, especially to fellow survivors, and when I started doing that, and started getting a positive response from people, that boyfriend at the time almost took that as a personal attack to him, he was intimidated, I guess. And he used to tell me that everyone who was working with me, was only working with me because they wanted to sleep with me, just such a shitty thing to say, right? Because that means that I don’t have artistic merit, it’s only because I’m a sexual object in the eyes of these people, that’s the only reason that they’re giving me their time. Which of course was not the case. But yeah, I broke up with him. Little things like that, you know, like, things that I felt were not were not adding anything positive or productive to my life. And then, where I felt that I was missing them that positivity or something productive or constructive, then I went out and found it. So that’s when I found the band, that’s when I found Paul and some of the other musicians that I’ve been playing with. And since then, it’s been like a really, really important journey of, you know, every six months or so taking stock and shedding what doesn’t help me or doesn’t serve me and seeking out new opportunities or new vehicles to heal and to be creative as well. Yeah. So yeah, to answer your question, the songwriting thing is more recent and it’s really when I decided that I didn’t want to live the rest of my life as an angry, bitter person and I decided to, like, use my experience to do something good for other people, you know, and share what I lived through.

I love this on so many levels. I think it‘s really inspiring just to have some like to not break down in the face of trauma and to have the strength to like, bullet point your life and tackle everything that is wrong. When you‘re in a position where things are not going well for you it‘s very easy to just stay there. Because it‘s comfortable.

Hanorah: Absolutely. Yeah, exactly. Like you said, because it becomes familiar and it almost becomes like a security blanket, right? Like when you when you develop bad coping mechanisms, or like weird attitudes and stuff. Changing feels like it’s impossible when you’re in the middle of it but I think it’s like with anything else, like if things get bad enough, at a certain point, you have a choice, like when you’re at that rock bottom: do you give up or do you want to try to have one day that’s better than today? And I don’t know what it was, I think part of it was like, it didn’t feel fair that like the person that hurt me could just kind of go on and live the rest of his life and then I would be sort of stuck at like the maturity of an 18 year old and never fulfil my potential and never be happy. Something about that felt so deeply unfair. And like it ticked me off. So I think I just like part of it was that, part of it was like, ‘No, the story doesn’t get to end this way’. And part of me reaching that conclusion came from reading about the testimonies of other survivors. Because at the time, I wasn’t, initially I wasn’t seeing a therapist or didn’t get help, because there’s still a lot of stigma around it. This was before MeToo and I’m from a traditional Catholic family so there’s a lot of taboo around anything like that, you know. So I kind of found support by reading blog posts and interviews and stuff from total strangers who could validate those things that I was thinking in my head of like ‘No, that shouldn’t have happened. No, it wasn’t my fault’. And that was like, the main snap that I had in my head is like, it wasn’t my fault, I don’t deserve to live angry for the rest of my life.

You‘re clearly very open about this trauma in interviews and as part of your background, I‘m wondering if a part of you deciding to be so open about going through this trauma came from wanting to be the voice that you looked for when you were healing, and if you hesitated at all, to open yourself up to this because as much as we‘ve progressed, we still live in a society that is full of judgment, and you know, there are bad people everywhere.

Hanorah: I think the main the main thing was like me, having had access to stories from other survivors, really helped me. And I guess as enough time went by and I felt like I was strong enough to talk, I felt like I had an obligation to talk because, kind of like you said, like even now it’s a society where that conversation can be dominated by what I would definitely consider to be the wrong side of the narrative. Every single woman that I know, has been through a similar situation, whether it was verbal harassment from a stranger on the street, all the way to a years long sexual abuse by a family member. And to me, I don’t know maybe because it happened to me and I was filling my head instead of with shame and blame which is the common thing, I was filling my head with stories of people that were validating what I knew, which was that this was wrong, it wasn’t my fault, and that our society doesn’t handle it properly, our justice system doesn’t handle it properly, and my own family didn’t handle it properly. So I feel like when I came to a point where I was strong enough to talk about that, and I feel like I had my my thinking right about it, I definitely feel like I had an obligation to be open about it. Because, you know, as much as I went out and did the digging for myself, I know how overwhelming it is to Google ‘What do you do if you’ve been raped?’ like, it’s really hard to confront even that word, when you’ve been through it, some people, it takes them 20 years to even use that word if they use it at all, which is of course up to them. But for me, it was like well, even if I’m just like doing little interviews with college radio stations, or whatever it is, it doesn’t matter, if I’m talking about it to one person or to 10 people at a show or to 50 people at a show or in front of 3 million people on TV, which I’ve also done, I felt like I had a purpose, like a calling. Maybe it’s not going to be my calling forever, but I felt like I needed to share that the shame does not belong to survivors, and that it’s possible to heal, you know, and it’s possible to live a happy life and find support and not feel like you’re bad or whatever, because somebody else decided to hurt you. Because it’s really easy to get your thinking backwards after a trauma like that. And I felt like, once I had gotten out of so many bad thoughts, I felt like I needed to tell every other person that had been through it like, ‘Whoa hold up, this wasn’t your fault, you deserve to be happy and healthy’.

Have fellow survivors or like people who, through your music or just you talking about this, you‘ve helped, reached out to you?

Hanorah: Absolutely, I mean, sometimes it’s as simple as like, a private message on Facebook saying ‘I heard your story, or I saw you on this show or whatever and I lived through the same thing 25 years ago, I never told anybody’ or sometimes it’s at a concert, and it’s like an 18 year old girl and she just is like crying and hugging me after the show and doesn’t say anything. So I think every person has a different way of communicating specifically to me about it. And I feel like it’s definitely torn down a lot of walls between artist and audience, when you share things that are that personal, because you’re kind of showing the world that you’re a safe person to talk to about those things. And you really quickly develop a sense of solidarity, even friendship sometimes, like I’ve had fans turn into real genuine friends just because we first interacted with each other on this commonality of ‘I’ve been through the same thing you’ve been through, I understand the pain you’re going through’. So yeah, I’ve definitely been able to connect with a lot of people that have lived through the same thing and that were thankful to hear it. Some were just like ‘You go girl, my sister went through this and my friend went through it’, you know what I mean? That’s the thing, the more the conversation is in the hands of the survivors and in the hands of people that want to make positive change, the more positive an effect it can have, the greater the effect it can have, I think.

Now going back to the songwriting part of it. What is it that you saw in music and songwriting that made you want to turn to that after you went through trauma?

Hanorah: Well, there’s sort of like a two part answer to that. The first part comes from the writing of the songs and the second part comes from performing the songs. So in writing songs, like when you’re just alone in a room with your notebook, writing down words, nobody’s coming in to interrupt you or stop you or silence you, or invalidate what you’re saying, there is nobody supervising and trying to control the narrative there when you’re alone with your notebook. And there’s power in that, there’s power in writing. And then the second half of that was also the power and freedom of kind of a similar dynamic of being onstage, like people don’t really heckle in the venues that I was playing when I was first starting out. I felt safe on a stage because there’s an inherent respect of the role as performer and the role of audience and that you don’t really cross the physical boundary of the stage and the crowd if that makes sense. So kind of being up there with them, but not, you know, only accessible in the content that we’re sharing, not in a physical way, it felt safe. And it’s also so much fun and so healing, to just jump around and dance and sing your head off and just kind of hear your own voice reverberating through a room and repeating your own lyrics and your own mantra of “it wasn’t my fault, it wasn’t my fault”. That is so healing and important. I also learned recently that when a person has PTSD, it can cause a literal break in your brain between mind and body, like a disconnect, and one way to kind of mend that disconnect is through physical activity, and playing a show is so very physical, from the ritual of being at home and putting on my makeup, to getting on a bus to go to the venue, to helping the band load in and setting up all the gear. And then playing the show itself is like the dancing, the singing and the moving around. It’s a very physical, spiritual experience if you go into it with the right mentality, like a sense of purpose, I guess and a sense that what you’re doing is important or even sacred. When I would go into a show with that kind of attitude, it’s like something else would take over me and I transcended where I was and it was just about opening up my whole entire soul, like a door, and letting all the light and all the garbage spill out at the same time. And for me, the beauty and the freedom and the power was in the contradiction of like, I’m half-broken and I’m upset, but also I found a new purpose, and I’m standing here in front of you, I’m alive, and I’m productive, and I’m semi-functional, and I’m sharing this music with you. And I would get a positive response from that. So I think that’s what it was. Part of it was honestly writing the truth about what happened. And then the physical act of sharing that with a crowd, in a safe space. I kind of stumbled into the performance part accidentally, I didn’t anticipate that it would be a healing thing to perform them, it’s just something you have to do you know, you write songs, you’ve got to sing them. And then once I started doing it, I started realising, ‘Oh, holy crap, this is where it’s at. This is where you get to connect with people and create something new from the songs, you don’t just repeat exactly what’s on the album or on the recording, you have an opportunity to sort of be spontaneous a little bit and engage with the here and now because every audience is different’. And that is like so moving and powerful.

Just hearing you talk about it, I realised something that I don‘t think I‘ve ever thought about performance before, there is something so empowering in a woman being onstage and setting her own limits, like, ‘I am going to tell my story, my voice is going to be heard but you‘re not going to get past this boundary that I am setting‘.

Hanorah: I think that’s a really important point. I don’t know if I even thought that way at the time. But absolutely. I think it was a way of taking the control back of my own story and absolutely setting a limit of like ‘This is the reality that I’m willing to engage with you about, I’m not willing to listen to any deniers, I’m not willing to listen to any apologists. I’m presenting the reality of what it is here and now and take it or leave it’ kind of thing. Yeah, that’s absolutely empowering.

So you started writing music and making a name for yourself, but I also read that you were then on La Voix (Québec version of The Voice)?

Hanorah: So I guess it came to a point, like, I was trying a lot of shows. And I felt like, I was really onto something like I was, you know, as a performer, I felt like I was getting better and better. As a singer, I was getting better and better, even as a writer, and then I did sounded like, ‘Okay, here’s the thing with that show: a lot of artists are kind of on the fence about, do I go on there or not, because you get a lot of visibility but you don’t want to get stuck in that, you don’t want to get known only for doing that show. And I think a lot of people go into that kind of American Idol type of shows thinking that it’s going to make the career for them if they win or whatever. But the truth is, for here anyway, for Quebec, and for that particular show, the best thing is just to go, if you’re going to do it, you go on the show, you be yourself, you don’t really make any compromises, you sing as best as you can, and you be exactly who you are. You bring what you are to that setting and you let people decide for themselves if they’re into it or not. And in my case, because I guess, of like the vocal ability or whatever, like, that was enough for people to latch onto after the story, because I was honest about the story on the show and everything. It’s one thing to hear somebody talk about something really difficult they went through, but it’s a show about singing, right. So I think I was just like a good enough singer that it connected with people. And the good thing also for me about that show is that I did not win it, which is a good thing because many people who win that show, they put out an album, maybe a second album, and then you kind of never hear from them again. But for me, you know, there’s other things going on. I was already booking my own shows, I was touring a little bit, I had already recorded some material, I was already building a bit of a buzz anyway, before that show. So for me, it was just like another thing, another activity, another stepping stone. And that’s how I was able to connect with my record label. And in fact, the musicians, there’s a band, or this duo called Les Soeurs Boulay, which means the blue lace sisters, they were like guest coaches on La Voix and they really liked what I was doing, so they should showed one of my performances to the head of the label and that’s how I connected with them. Which is exactly what you want, to build organically and not become like, a superstar overnight and then fizzle out in a few months when there’s the next one.

It‘s very complicated and interesting to watch the relationships artists have with shows like this after they leave it.

Hanorah: I feel like those things are idolised because you come to connect with what you see on TV and you want to see yourself and the people you’re watching. So you think that it’ll make other people feel the same about you if you go on, and it will. But a career doesn’t start or end on a TV show if you’re a musician, you really have to have other things going on. And it’s just like a step in your journey. I see people now who did La Voix and this is just a Quebec show, we’re not even talking about a market as big as the United States, but just in Quebec, people who have done the show, like eight years ago, and it’s still like one of the first things in their biography, like, ‘Oh, yeah, they did La Voix in 2011’. And they played one festival and like that’s their whole bio, but what have you done since then? You’ve had seven years to put together even just like $500 to record a little EP or something. You got to do something. I think that also, at a certain point, I think it was also like, once I realised I had something important to say, I decided that it deserved a wider audience, not just short-term like on La Voix, but I decided that I would go as far as I could with the project and play to as many people as possible, initially because of the message, but also purely just because I believe in my own talent now, too, I think that I have the capacity just on my musical merit to go that far. So you make the decisions. You make career decisions to that end, you don’t just kind of hang out and do nothing, you know, they’re not going to come to you.

How did it feel to have your voice amplified like that? Because I feel like it might be jarring to just be there. But also very important, if you like, like you like you have a purpose. It‘s bigger than you.

Hanorah: On the TV show. I mean, it was kind of crazy. Because even though it’s just Quebec, it’s the largest and most viewed show here. I know that they get like something between two and three and a half million viewers every episode, which is astronomical, for here, like the population of Montreal alone is 3 million. And Montreal is the biggest city in the province and one of the biggest cities in the whole country. I think it’s the third biggest in all of Canada. So 3 million a week is I mean, Canada has 23 million people in it that’s like, the whole country over an entire season, if that makes sense. So, like, it is like a bit of a taste of an overnight success story, a little bit of a taste of it. Short term, though. People have a short enough memory that if you release an album a year later, they’ll be like, ‘Oh, yeah, her I’ve heard her before’. But initially it was kind of weird. Like, I had a hard time leaving my house a little bit for a little while, because every time I did people would come up to me and talk to me, like, ‘Oh, my God, I saw you, it was so crazy, my God’. But what they were connected to, those who were coming up to me to talk to me anyway, I don’t know about those who recognise me didn’t say anything, but for those who were saying something they were connecting to ‘I saw you on my TV screen’, it wasn’t ‘You have an important story to tell’. So the people who would talk about the story and the purpose would do it privately by message or like in person at a show not so much in the middle of the street or on the bus or anything like that. So it was kind of weird at first, because it felt like there was some aspect to the show that fundamentally contradicted the reason of me going on the show in the first place, but I kind of went into it knowing that it would, and knowing that people have a funny relationship with their televisions. Again, like just kind of re-centring to the goal of like, being who I am, and bringing that to the show and trying to make friends and have a nice time. Because it’s long days of shooting and stuff too. It’s really tiring. They paid a little bit but not really a substantial amount to do the show. Which I didn’t even know that we were getting paid in the first place, so that was cool. I don’t know, it was strange. And then after that, like whenever when I played shows, people would come out and it was like a transitional time, where now there’s a bigger audience than I anticipated or was ready for and a more mainstream audience, because before it was more like underground, a lot of university students, like-minded individuals who even if they hadn’t been through the same thing, they could dig it. They’re like, ‘Yeah, this is an awesome chick who’s speaking her truth’, but then people who watch La Voix and then come out to your show expect something a little bit different from your show, they expect something more in line with more mainstream artists here in Quebec. Which isn’t like American Top 40. It’s not like Ariana Grande, it’s maybe more like The Lumineers or Ed Sheeran, but on a smaller scale in terms of the vibe, that’s kind of like what’s popular here. And that’s not what I’m doing at all right, I’m doing like, soul, r&b, funk music, and there isn’t really like a cultural context for that here. So those are some difficult factors. And I don’t know it’s a lot to process because I’m an English-speaking person, and artist here, and this is mainly a French province. So that’s like a whole other thing. And I’m an ethnic minority here as well. And this, you know, area has a really notorious little hub of racism going on, too, so that’s a whole other thing. So it was definitely a different audience than I was used to before. But at a certain point, I think I I kind of got used to having different types of people expecting different types of things for me, and what it all has to come down to is me feeling good, and being proud of what I’m putting forward musically in the message and in the show. So that kind of has to stay the focus of like writing the best songs and putting on the best show and trying to be as honest as possible in songwriting.

I‘m interested in the title of the EP, because I know that it‘s a lyric. But when I listened to it as a lyric, to me, the song is very strong and so you're like, “it‘s going down for the good guys and the bad guys”, it‘s like nobody‘s safe. But when I see it as a title of the EP, I see it as something that‘s super inviting, which is like this is for the good guys and for the bad guys.

Hanorah: I love that so much. I love that. Because like in the song “Going Down”, it’s kind of like about performative allyship and performative wokeness. So like, since #MeToo, I’ve kind of noticed this little pocket of, especially guys, who will be like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’m so feminist, it’s awful how you women are treated’, but then they’ll cheat on their girlfriend, you know? There’s like a hypocrisy in a lot of like self-proclaimed liberal men or progressive men. And I find that really frustrating because they’re the definition of the establishment and won’t go out of their way to actually do anything to help or just kind of talk a big game, but still uphold really harmful behaviours and values, like in their craft, in practice, in life. So that was the initial idea of the song. But also, bigger picture, part of this whole journey of the healing has been me realising that I cannot or should not use what happened to me as an excuse to justify any behaviours that I have that are not chill on my bad days, if that makes sense. Everyone can find an excuse to be shitty to other people, ‘Oh, my parents got divorced’, or, you know, ‘I grew up with this happening, or this happened, or that happened’, and everybody saw it that way, and behaved in accordance with that. And everyone would just be really awful people all the time on the outside. But in reality, we’re all human beings with the same wants and the same needs, that need to feel heard, the need to feel safe, the need to feel community and to feel validated. And it’s up to each of us, despite whatever pain we carry, just to find a way to still be decent and civil with other people and with ourselves. So the good guy and the bad guy, you are both, and it’s up to you to decide every single day, which one you’re putting forward, which one you’re nourishing and which side of yourself that you’re allowing to grow. Because for me initially, after the assault, I was letting the kind of ugly take over, right, because I was traumatised. But then it came to a point again of like, ‘Okay, well, that was three years ago, and I’m still angry. So I need to do something I need to make a change’. So it’s kind of about that, too. And another thing is, I don’t think that people like to think of themselves as a bad guy. I don’t think anybody does, including my rapist, because I confronted him about it, he’s like, ‘Oh, you think I’m this bad guy, blah, blah, blah’. And that really resonated with me, because it’s like, ‘Well, your actions say you are, so what evidence do you have that you’re a good guy?’ You did other horrible things, too. mean? People don’t want to be accountable a lot of the time, I feel and I feel like, it’s the people that carry the most pain that have the hardest time with that, except for like, really heavily narcissistic people of course. I’m kind of going off here, but it’s sort of a complicated question because of the nature of trauma and healing and the fact that people that do the most damage, often it’s because they had a lot of damage done to them and haven’t found a way around their own lives after the fact. So it’s kind of like a cycle. So I feel like, it’s important to acknowledge that everybody has both those going on inside of them, both an inherent human decency, and also a really dark side of us that can have the capacity to hurt other people if we’re not careful? Or if we want to hurt other people. And it’s like a call to everyone to kind of look at themselves and their actions, and their true motivations behind them and see what makes you think you’re good. And what also makes you think you’re bad, you know, because I think also a lot of people are really hard on themselves at the same time, in some areas of their lives, but then they’ll ignore their own bad behaviours that really need to be addressed. So that’s kind of like the trick of the album title. It’s like, nobody’s off the hook but everyone deserves healing at the same time. It’s so hard to put that into words, because the song itself is really militant and strong and like “it’s going down”. But yeah, I mean, good guys. Bad guys. Nice guys. Like you know, those guys who are like, ‘I’m a nice guy, why don’t you date me?’ Well, why are you a nice guy? You just called me fat. You just called me a bitch, that kind of thing. You know, what evidence do you have that you’re a nice guy if your behaviour’s so shitty? Like, maybe you should go examine yourself a little bit before you come at me. The whole EP is sort of like that, like who are you really?

It‘s so important as well, to recognise that in order for you to self-examine, you already have to be like, on another level of self-awareness.

Hanorah: Absolutely. And I think part of that comes from something that you picked up on earlier about, when we were talking about the initial moment for me of like, deciding not to live a shitty life and taking action. But you also said that, like, you know, sometimes it’s hard to do that, because it’s familiar or comfortable sometimes, even when you’ve developed a bad coping mechanism. And I think that’s a large part of it, too. I think a lot of people, narcissistic or not, kind of come to rely on their flaws if that makes sense, almost as an excuse. Because if you if you are unsuccessful or unhappy, if you could only find something to blame it on, that means that the problem, wasn’t you. But the truth is that the hard, right thing is to look at the ways in which you are helping and hurting yourself and other people. So yeah, it definitely takes an amount of awareness. But I also think the main thing is that it takes a certain amount of strength and agency and I think that a lot of people have a fear of confronting that, because they’re afraid of coming to the conclusion that they were bad all along. But nobody is all bad I don’t think. I think that everybody has potential to cultivate good in them, but it’s about the choice is what it is.

I want to talk to you about “Clementine”, which you did mention earlier in the conversation, because it was one of your older songs. Since it was really born out of the trauma and that moment in your life, and now, you know, a few years on, endless hours of therapy and work on yourself later, you have a different outlook on life. How does it feel to perform something that was born out of such pain, to now re-contextualize it with your new outlook?

Hanorah: I get asked that question almost every single time that I do an interview, I just I don’t really know how to answer it fully. Because I feel like maybe because enough time has gone by, not that it’s lost its meaning or its power, it’s more that I can let it be what it is. And we’ve also performed that song so much that part of me kind of sick of it, not because of the lyrical content, I think it’s really important, but more just like we beat ourselves over the head with the arrangement, like we’ve had so many different arrangements of the song from that first version to the first version with the band, and we recorded it like seven different times, and then finally released the version that you have on Good Guys Bad Guys. So I think I’m honestly a little bit sick of playing it just for the musical side of it, because we’ve really beat it to death. But lyrically, every time I perform any song, whether I wrote it or not, I have a sense of duty to honour the content of it, or at least, you know, open up that channel, letting energy flow freely out of me. And also, because we play it a little bit fast, I also try to focus on getting the pitch out right, because it’s really hard to sing that song that fast. So part of me is stuck on the technical side of it while I’m performing it, and then I’m also trying to give it energy and emotion. So I think it’s more about the performance maybe, with that song, than with the content because it’s an older song and like I said, we had so many problems with it with the arrangements over the years that I’m kind of over it, you know. For other songs like “New Orleans”, for example, every time I perform it, I I feel like I’m really connecting with where I was at when I wrote that one. It’s kind of like my love letter, my thank you letter to every person that’s ever helped me on this journey or given me a venue to play or lent me a guitar or anything like that, and I always feel like a little pang in my heart when I play “New Orleans” because it feels like a farewell song, like ‘Oh, thank you, I hope we meet again’ kind of song. And for some reason that always gets me right in my heart whenever I perform it. But it’s also a slower and more introspective song, so I have the space to do that. “Clementine” because it’s faster and more upbeat when we play it live I’m just trying to sing the right notes and not like be flat or sharp or anything like that.

That makes sense. So about “New Orleans”, in your lyrics, the city represents the fulfilment of a dream or a wish. New Orleans isn‘t normally the city that people talk about when they‘re like ‘I want to go somewhere!’ It‘s either New York or LA for their own weird reason. What is it about the city of New Orleans or the image of it that conjured up these feelings in you that made you want to put it into song?

Hanorah: This is gonna sound kind of strange, but it’s about that city’s relationship with their dead bodies, how they deal with the dead in that city. There’s a romance around it, and because of the mixed cultures and everything, there’s a mysticism that outsiders have about that place because of like different spiritual practices that go on there. And it’s complicated, because like there’s a cultural aspect to that and there’s also a geological aspect to that, like they’ve experienced so much death because of natural climate and disasters and things like that. The reason I thought of New Orleans is because of their cemeteries and the way they deal with their dead bodies and it just kind of feels like a resting place to me. It’s the birthplace of a lot of the music that I really love and it feels like you’re going home to God or like chickens going home to roost kind of thing, I have that image of it, for some reason. Part of it is because of what I know of the culture and the music and also part of it is because of the way they deal with their dead bodies and the above-ground burials and reusing of mausoleums and what happens when the cemetery is flooded, and caskets coming out of the ground. There’s something about all of that that feels like – there’s an inevitable end to my story, and it feels like before I get to that last place, whatever my final days are going to look like, I want to live my days with as much gratitude as possible, as I’m on the cusp of accomplishing all these things like you said. I’m also aware that every story will have an end and I just want to feel grateful and feel like a lot of love in my heart through the whole journey if that makes sense. So that’s kind of like a symbolic thing.

It‘s really odd to have someone who's at the start of their career already thinking about the end of it, or end of life I guess. I feel like the inevitability of mortality and things ending is something that people choose to ignore, but it‘s a part of life. What‘s your relationship with the idea, fact really, that everything will come to an end some day - does it motivate you or do you just embrace it with a lot of peace?

Hanorah: A little bit of both I think, because I think that the awareness of our own mortality is something that moves most humans to do a lot of the things that we do, like the idea of a legacy, right, like leaving something behind. Whether that means having a big family or making a lot of money, or helping a lot of people, I feel like we’re all kind of attached to some degree to the idea of a legacy. But funny enough, when I was initially assaulted, one of my symptoms was that I had strange, intrusive thoughts about death and dying, not suicidal thoughts or suicide ideation, just involuntary thoughts about death. And part of my journey of dealing with that was to confront it. I took a class in college called Views on Death and Dying and for some reason learning everything that I could about death at the time really helped me. It helped ease a lot of my anxiety around death and, like you said, sort of embrace it as a natural order of things. I wrote a couple of short stories about it, some poems about it. And even today, do you know the YouTube channel called Ask a Mortician?

I don‘t!

Hanorah: It’s so good! It’s like this young mortician, and she owns a nonprofit funeral home and she advocates for natural burials at opposed to embalming, which is bad for the environment. She encourages families knowing what it is that they legally have to do and what they legally do not because the funeral industry is an industry, it’s a multi billion dollar industry and a lot of funeral homes scam grieving families out of money, take advantage of them. But she also talks about a lot of philosophy that different cultures have around death and dying, and different anecdotes and stories. And I don’t know, something about that really helps me when I feel stressed and more recurring thoughts, or intrusive thoughts about death start coming up. It helps me to just kind of explore those thoughts in a safe space with a sort of guide that can kind of guide me through it, if that makes sense. Maybe fascination is the wrong word, but like, my considering of death and the dead is sort of part of me healing at the same time. Because it used to be this big feeling of dread and doom, like I said, when I was initially assaulted, but now it feels like a natural, safe thing to talk about. And I feel like it’s the same thing with assault. You know, the things that we’re terrified of, are the things that make us feel a lot of pain or a lot of grief, because that’s what it is to be assaulted to be forced into a state of grief. Just like when you lose a family member, because it is loss, you do lose something of yourself. But I think that going through like a natural, healthy conversation with yourself about these things, is what’s healing the most. And since I really want to make sure that I’m in a good headspace and that I can get through my life as a happy, healthy person I feel like it’s important to me to think about, and explore all those things that I have funny, difficult relationships with.

Now I want to talk about another potentially more ‘out there’ theme. I‘ve always loved Saturn, it was my favourite planet as a child and I don't know why, and you have a song called “Saturn Return”. I love the image and the lyrics of Saturn returning and it feels a little out-worldly and connected to a different plane if you know what I mean. So what is your connection to this planet? What’s the story behind the song?

Hanorah: So it’s actually Paul who came up with the title of that song. He’s a really special person. I met him in Montreal when I was going to university for art and he was in the metro and he was busking, playing guitar, and he had looping pedals and stuff. So he had loop of bass and drums and rhythm guitar, and he was just shredding, soloing, the most soulful blues licks, but really shredding it. He’s about my height, about my weight, but kind of very, like lean, and with dreadlocks down to his hips almost. And I was just kind of blown away like what is this creature? He seems really small, but his sound was so big and it just hit me right in my heart. That’s kind of why we started working together. And he’s kind of a genius. He won’t admit it but he’s kind of a genius. And one day, he was just walking down a street, he said, and the guitar part, like the melody that you hear on the guitar just popped into his head so he tried to hold it into his head and not forget it until he got home and could like write it down or whatever. And he told me that he was thinking about the 27 Club, you know, musicians and artists who passed away at the age of 27. And there’s a theory that part of that is because of Saturn return, about how it takes 27 to 30 years, something like that, for the planet Saturn to come back around to the same position in the sky as it was when you were born, like it takes 27 years to come back around. Which is why it might explain why that period can be so difficult for humans, especially if you’re coming to new responsibilities, things like that. So he told me about that. And around the same time, both he and another one of my friends who were at that age, were both separately going through a really difficult time, and they both sort of like disappeared and didn’t tell anybody where they went, in the same year. It’s complicated because they were both going through their own separate hard times and it’s really about them, not about me. One of these friends who kind of disappeared and didn’t tell anybody where he went, was going through his own hard time. And we’ve talked about the good guy, bad guy thing right? And he continued to be destructive. So it was a person that, although I had a really strong connection with him, and he was a very important person in my life, it came to the point where it was like, ‘well, I can’t be a friend to you anymore because of these behaviours and a lack of maturity, really, a lack of self awareness and a lack of accountability’. And it was just coming out in all these weird ways. And I was like, okay, not to abandon the person when they’re going through hard time, it’s not that, he had all the support he needed, it was just a lack of willingness on his part to do better, and to be a better person. And, you know, when that starts to affect people around you, we all have a choice to hang around or not to hang around. And I decided, and most of the friends around him decided, you’re not a person that can be around if you’re being this destructive. So the song is kind of like my way of saying ‘Farewell, maybe in another 27 years, you’ll be healthy, we can be friends again. But for right now, I’m kind of at a loss because I’m saying goodbye to somebody I don’t want to say goodbye to’. So yeah, the initial Saturn part came from Paul, I guess, because he told me about the 27 Club thing and it just happened to fit in perfectly with what was happening in my life at the time with that friend.

That’s so beautiful. So heartbreaking but so hopeful as well.

Hanorah: Yeah, it is. And there has to be an acceptance also of like, you know, it is like a funeral song in a way, it’s sort of an afterlife kind of thing too because maybe not, and maybe it’ll just be a never again, kind of thing and how do you accept that? Because he was such a powerful presence in my life, this person, and it’s hard to be hurt by people you care about and it’s hard to admit that you’ve been hurt and make this smart decision and leave. And that’s what it is. It’s like, despite whatever he’s going through, he’s hurting me, so I have to love myself and take care of myself and walk away.

Watch: “Saturn Return” – Hanorah

The music video is gorgeous.

Hanorah: Oh, thank you so much.

How did you come up with that idea of the several different scenes?

Hanorah: Oh, the video, honestly, I have to give complete credit it to the video production company that made it. They’re called Bald Man. I met the two people that run that company, Catherine and Xavier, around four years ago, because they did a video for me for one of my songs on Post Romantic. At the time they were new, I was kind of new, but I still really enjoyed working with them and they did a lot of really good things. So I said, ‘Okay, when I have some funding to give to you, and when I have a bit more of a career established, we’re going to do another video again’. And then it came to that point, I signed with the label and recorded the album, and we were going to do a video for “Saturn” so I wrote to them again and I said ‘The time has come, do you want to make a video?’ And they said ‘Oh my god, yes, we do’. And they do a lot of like hip hop and trap videos and edgy teenager type of content, and they wanted to do something really different to honour a sort of David Lynch, surreal kind of a space where you’re looking at in between space, waiting for nothing, if that makes sense. So they had a really amazing stylist, her name is Delsey Ruel-Bilodeau, and she also did the art direction on that. So Catherine and Xavier went out and scouted all these different locations and these little remote villages all around Quebec. And so we did one day of shooting, we started around 8am. The first location was in that theatre with the golden curtain behind. And then we just kind of went from one location to the next all throughout the day and knocked it out. But they’re the masterminds behind that video, they, my gosh, they did a great job.

I think we’ve really touched upon this throughout this whole conversation already, but what do you want people to feel when they listen to their music to your music?

Hanorah: I guess there’s like, two sides to that. From the recordings and the live shows, right? Regardless, I hope that it just feels good for them and that even if they don’t relate to what it is that I’m singing about that, first of all, the music stands alone in and of itself so that people like it, but I hope that we can transmit something that’s heartfelt and genuine and unique. I wanted there to be something that maybe they can’t put into words that they can connect to regardless of what it is that I’m singing about, if that makes sense. And I think a lot of that rests in the vocal performance. I put a lot of pressure on myself for the vocal performance to try to just try to be as genuine as I can. That’s hard sometimes when there’s a deadline or schedule or money involved with studios and stuff, but especially for the live show, I really try to make that my priority, especially for the more emotional songs. I hope that they feel that they’re not alone. That’s a big one. That’s always going to be the thing because I try to tackle things that I struggle with so that other people can kind of – just like right now when we talked about all this stuff, you pulled half the weight of this conversation and put things into words that I could never put into words, but you still understood what I was trying to say, you know what I mean? And I think that solidarity and compassion is really important and I hope that that’s what comes through.

Let me just say, having seen you live, that 100% comes through.

Hanorah: Thank you!

A very quick last question: what was the last great thing that you listened to?

Hanorah: Oh, my gosh. Okay, hang on. There’s a live performance that Aretha Franklin did before she passed away. I think about four years ago, I think it was in 2015. There’s that Carole King musical, right? And she did a surprise performance, Aretha, she showed up because Carole King was in the audience and she surprised her by showing up and playing “Natural Woman”. And she’s like in her 70s, of course, but her vocals are still out of control, of course. I’ve watched that video so many times, and every time I do I need to turn off my phone and sit in silence for a while because everything that I want to give in performances, she just throws it out there like it’s nothing but it’s so powerful and masterful, and it just touches me right in my heart. I cry every time. Give it a watch if you can, because I don’t think that there will be anybody that rivals that woman ever, ever again. I have goosebumps just thinking about it. Honestly, I couldn’t articulate why that performance is so important. It’s just what I feel like a vocalist needs to do. If that’s the centrepiece to the band, or the project, and the vocals are what’s important than what she gave at that show is like, mic drop. Nobody else needs to sing a song ever again.

— —

Connect with Hanorah on

Facebook, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

?© GRL Photographie