The widespread use of technology sometimes makes us worried that music, art—really any forms of self–expression–may become less genuine. Does something get lost when a computer is brought to a live performance? Are the songs we typically hear on the radio becoming more produced, further from the spontaneous, fleeting, artistic vision of their genesis? Is there something so much more human about painting or drawing using physical utensils, not a digital toolkit? Just a slight waver of the hand that doesn’t quite show from all the button-pressing and clicking?

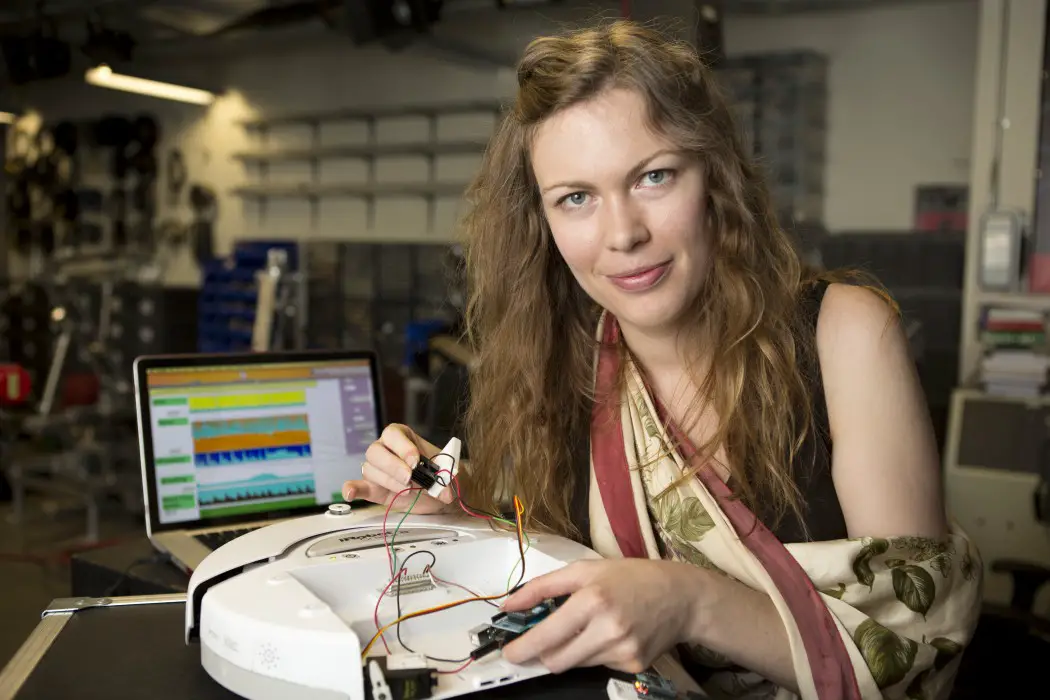

These are all valid concerns, but many artists have used technology to aid them in producing work that seems to reflect, even call upon our inner worlds in new and exciting ways. Erin Gee is a Canadian artist who “adores all things robotic, cybernetic, and virtual” and wants to “create worlds where human and robotic voices intermingle.” Recently, I had the chance to chat with her about her recent work, “Swarming Emotional Pianos,” and the discoveries she has made in the process.

What do you find most appealing about the human brain?

I appreciate the complexity of nature, its mystery and above all its uniqueness, but this is to say that I very much so value animal brains as well. The focus on the human brain as the pinnacle of nature’s creation is an old, traditional idea that places man at the top of an evolutionary hierarchy. I think that by revaluing animal and machine perspectives that humans can achieve greater humility and learn from others, simultaneously revaluing their own brains in different ways. Nature is always in flux, evolving, and these elements of potential chaos, growth and death are important to value and maintain in technological culture. Otherwise I think that everything gets very politically boring: toys and cellphones that get increasingly better, smaller, faster are only nominally surprising, and don’t have a lasting or significant cultural impact. Integrations between technology, the body and nature are brave and strange.

Tell me about your project, Swarming Emotional Pianos.

My latest project features a fleet of mobile, robotic chime instruments with integrated lights that perform music. Imagine a surround sound piano distributed in space, that moves around. While this is already a very intriguing tool for new music composition, I made it specifically for the performance of data-driven music that comes from an emotional body, live. So to play this piano, a performer is strapped into a series of sensors that gather information about heart rate, sweat release, breathing, and blood flow. Then they are challenged to feel, in order to affect these physical elements that shift during mood. So while humans can see large emotional peformance of the body such as blushing or crying, there is another world of micro-performances that my system seeks to amplify.

While simply conjuring up emotion might sound impossible or surreal at first glance, I think most everyone has probably experienced a situation where thinking about a recent situation can make one tense and frustrated, or even bust into tears or jump in excitement. Method actors are trained to use their memories like this to conjure real emotions on stage, so these method actors are the perfect instrumentalists for my performance.

In addition to the sensors already described, my collaboration with neurophysiologist Vaughan Macefield (Marcs Institute, University of Western Sydney, Australia) allows for pioneering use of microneurography in this process. Microneurography allows us to eavesdrop on the precise electrical pulses of a single neuron through the insertion of tiny electrode needles directly into a nerve near the knee. Macefield has correlated the activity of this nerve with emotional output, so it’s like tapping directly into the brain, but obviously less invasive. It’s a powerful tool for getting numbers to make compositions from. We are currently in a process of selecting method actors in Montreal, and testing them for the debut performance at Elektra festival in May, co-presented by new chamber music organization Innovations en Concert.

When and how did you conceive of the idea?

It was actually Vaughan Macefield who approached me after a performance of a robotic opera at the University of Western Sydney where I was performing my work Orpheux Larynx live with a choir of Stelarc’s artificial intelligence robots (I eventually met Stelarc in 2011 in Montreal and he invited me to come work in Australia at the Marcs Institute to develop the work). Vaughan simply introduced me to the potential to use sensors to get numbers from people who were effected by emotional stimuli as an art project, and we started working right away. The whole process happened really quickly.

What sustains and guides the emotional wiring you receive from performers’ bodies and brains, and turns those signals into the symphony you are creating?

Hmm, well I have been programming an on-board “brain” for each of the robots through a microcontroller, but it communicates wirelessly to my computer which is running a software called Max/MSP, which allows you to make computer programs in a visual way, like drawing lines between elements. So that part is fairly easy to explain. I have recently began collaborating with this amazing programmer in Montreal, Vanessa Yaremchuck, who is developing her software to do really exciting things to map the emotional data in unexpected ways. So I expect over the next few months there will be some massive developments in the music.

Do you think there is an inherent structure in our emotions, a sort of code, or algorithm?

I honestly don’t know, no one does. Vaughan has told me that this kind of emotional code is the “holy grail” of emotional neurophysiology. What I find significant is that the reason no one knows is because (at the moment) all the evidence seems to contradict itself: the sadness and joy of different bodies will tend to reflect different patterns and behaviour. As science is struggling with a problem of representing the data so as to find patterns, I think it is a perfect time for artists to step in and work with data creatively: celebrate difference, and have performers uniquely highlight their own algorithms through music.

Do you think we’ll ever get to a point where our thoughts can be a new accepted medium for art?

Oh absolutely. This point was actually reached in the 70s through performance artists such as Yoko Ono. While Ono wasn’t working with high technologies, she wrote beautiful text instructions that were intended to be completed by the viewer/reader of her text work. Therefore her work was intended to be “completed” through the imagination of the participant. Ono actually maintains an active Twitter account, a contemporary medium for disseminating her text work she started in the 70s. This really radical idea, of having “thought” be a medium for artistic creation, this is made more literal through the kinds of tools available to artists today–in fact I think that I have heard the term “neuroaesthetics” been used to describe projects like mine. Historians are already on top of this.

What have you learned about yourself, your own emotions, and your control over your emotions through your work?

Mostly I have learned to trust my instincts and take risks in my research. I don’t know very much about my own emotional control because I tried to have the needle stuck in my knee, I was so nervous and scared that it really complicated the session, as I have a phobia of needles. We gathered data for that session but Vaughan told me I was the second-worst participant he had ever had for that procedure, the only person worse was the one who fainted immediately. So I was heartbroken that I could not be a performer in my own work, but now I realize that I am not as expert in emotional performance as a method actor, so I will simply be the best at creating and nurturing the system.

What has your work taught you about humans?

As far as emotions go, I continually respect the human perspective and capability of humans to read emotions above all. Humans are naturally very shrewd in our abilities to read fine muscle contractions in the face, smell a faint amount of sweat, to notice when an expression is false. I think that machines have a long way to go in interpreting subtle aspects of communication in this regard, but still, machines offer a fascinating window into other portions of emotional communication. I have learned through my research into emotional neurophysiology about how automatic and responsive our bodies are to our environment – being in the presence of someone who seems nervous will make us nervous, for example, and this might be an unconscious thing. So I am fascinated for the implications of interconnection that this brings about – if our emotions are so closely tied into each other and our environment, then our bodies extend a little beyond our flesh in somewhat complex ways. A more down to earth way of explaining this is that phenomena where a terrible fluorescent lighting in an office environment can make everyone cranky – do the emotions belong to the individuals, or the environment, in this case?

What are three things most people don’t know about you?

1. I am really enthusiastic and fascinated by yoga. I am trying to learn more about how my body works.

2. I was am an avid video game player – starting at a tender age where I would play for hours as a child on my NES through my favorite game, Final Fantasy I, I am now really into the Xcom series and am currently playing a game on my cellphone where the main character is a virus trying to infect the planet with its contagion.

3. I am a feminist. I don’t think there are enough role models that say this, I am happy to have been given a platform to do so. It is really fashionable nowadays for celebrities to distance themselves from the term for example, and say these silly things like “I’m not angry” or “we should be over that by now” or “I had a strong mother and always was surrounded by strong women, I don’t get this.” Feminism isn’t about standing up for yourself, it’s about standing up for other women, who maybe didn’t have strong mothers or maybe were raised in positions less fortunate than yourself. Feminism doesn’t need to be about anger, because one doesn’t need to be angry to believe in equality. While feminism doesn’t manifest itself directly in my work, I do dream of a future where equality is possible between humans, animals, and if it ever comes to it, machines. It is utopic but I prefer this vulnerability to a fashionable cynicism, and I think that younger generations of digital artists and people are ready for more sincere, idealistic interactions with the world.