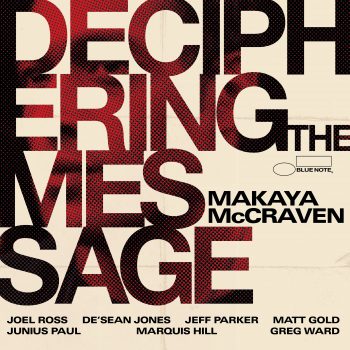

Makaya McCraven’s Blue Note debut, Deciphering the Message, intertwines past and present in an overlapping tapestry of sounds that are beyond typical remixes.

Stream: ‘Deciphering the Message’ – Makaya McCraven

In many ways, Blue Note Records has become synonymous with jazz. In the same way that mention of Motown conjures a sound, an era, fashions, celebrities, and more, Blue Note generates images of jazz clubs, New York City, and musicians like Art Blakey, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk. In Blue Note’s early years, the main focus of the label was hard bop and bebop, though as jazz morphed and expanded over the decades, Blue Note also became home to more avant-garde musicians like Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy. Rudy Van Gelder, the engineer who recorded almost every Blue Note session between 1953-1967, is known for capturing jazz on record in a way that no one else quite could, and is a large part of why those records still sound so good today. The legacy of Blue Note is its dedication to innovation. Their current roster houses jazz greats and prodigious young artists, and even extends beyond jazz.

Makaya McCraven, Chicago-based drummer, producer, and “beat scientist,” has joined the Blue Note lineup to create a unique project that celebrates Blue Note then and now. Following in the traditions of producers like Madlib and J Dilla, McCraven’s incredible ear for grooves and his great technical ability has always produced amazing results. Deciphering the Message (out November 19, 2021 via Blue Note) combines McCraven’s innovative approach to remixing with his own playing and contributions from his “musical family.” He dug through the annals of Blue Note’s history to choose recordings. Though all of them are from the 60s and earlier, the track list includes a wide variety of musicians, including Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Hank Mobley, and many others, each of whose writing and style is lovingly highlighted by McCraven’s deft production.

McCraven invited trumpeter Marquis Hill, guitarists Jeff Parker and Matt Gold, tenor saxophone player De’Sean Jones, alto saxophone player Greg Ward, vibraphonist Joel Ross, and bassist Junius Paul (all of whom have called Chicago home at various times) to provide newly recorded material that he then mixed with the historical audio, with the goal of blurring the edges of reality – he describes the “intriguing symbiosis” created by a mix of obvious sampling and a skillful masking of it.

In an age where anyone with a laptop can make beats, McCraven’s subtle magic is all the more impressive. Deciphering the Message intertwines past and present in an overlapping tapestry of sounds that are beyond typical remixes; each song is a love letter to the musicians who came before, as well as an inviting entry point for people who are new to these styles. To McCraven, the word “jazz” is “wholly insufficient to describe the phenomenon of what we’re dealing with.”

“In the continuum of this music, it has always integrated with all styles it comes in contact with,” he says.

Deciphering the Message is the product of that philosophy. It is expansive and inviting, full of warmth and openness – the same feeling that listening to Van Gelder’s original recordings provides. On this record, McCraven’s message is clear.

— —

:: stream/purchase Deciphering the Message here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH MAKAYA McCRAVEN

Atwood Magazine: For a project like this, how do you even begin choosing songs?

Makaya McCraven: I gave myself a few parameters, one being that I knew I didn’t want to deal with more contemporary music. The catalog I was going off of was from the 60s and earlier, so that cut off a lot. I didn’t want to be sampling anything that might have a backbeat or really any electric instruments — anything that was too modern. I wanted to deal with the classic nature of the Blue Note catalog. And there’s so much — if you go later, there’s all this stuff that I feel like would have been a little bit easier and more obvious to be like, “Oh, I can just grab that and that’s dope.” I wanted to avoid that, and I also wanted to try to not just make these beats, but try to make little pieces of music, as well, and have some some playing on here.

I also made lists of different themes and ideas to help me sift through it, but at the end of the day I was just listening, and digging, and digging. I wanted to investigate music that I wasn’t familiar with and learn some new places within the label. I sampled a lot of stuff that was just trial and error, and it didn’t make the record because it didn’t fit the same narrative. It was a lot of back and forth and just chipping away at it, until it became clear what the body of work was going to look like.

Did you have an idea of what you wanted that narrative to be before you set out? Or did it reveal itself as you worked?

Makaya McCraven: It kind of came out [as I was working]. Certain ideas I had early on ended up sticking through. But when I sat down with Don Was from Blue Note, after we knew we were doing the project, where I was like, “I have these ideas.” I’m thinking, this is a legendary producer, the president of Blue Note, like, let me get some nuggets, let me learn something right now. This is a cool opportunity. And he’s just like, “Yeah, sounds great, great ideas. I love it. Whatever you want to do” [laughs]. It was similar to the conversation I had with Richard Russell when I did the Gil Scott-Heron record. I’m grateful to [both of] them for trusting me, and for not wanting to get in my way.

With your reimagining of Gil Scott-Heron’s album, you were digging into the musicality of one person. With these all coming from different musicians, did you find yourself engaging differently with each of them?

Makaya McCraven: I think I’m going to engage differently with every piece of music or audio, or I’m gonna be trying different ways to recontextualize it or reimagine or find something new. It’s like, how do I use this piece of audio to create some new text or new collage out of what I have? I’m following my ear and the sonic side of it more than other conceptual things. But the Gil record was different, in that I was mainly dealing with his voice and the music beneath it to recontextualize his words. With Deciphering the Message, I wanted to make music out of historical audio that was already here and find things that connected with me sonically, first.

Then I was piecing this narrative together to try and really make a record and not just a collection of beats. Particularly in this day and age where, like, everybody is a beatmaker. It’s really accessible now to sample and make tracks. I like to blur the lines of what was sampled and what wasn’t. Like, “Is that a sample? Is that not a sample? Are those real drums?” It’s up to the listener to decipher. Sometimes I like it to be obvious that I’m sampling and sometimes I don’t want it to be so transparent — the symbiosis between that is an intriguing crack. One of the things I’m looking for in all of these projects is, “Where’s the edge of reality?”

I was going to ask how you conceptualize the art of remixing, and I think you just answered that. But is there ever a line that you don’t cross? Where does artistic license end, if it does?

Makaya McCraven: I think it’s a case-by-case situation. That’s a good question. I think when I look at it, I’m inspired by beatmakers who came before, and there are things I want to do with the music because I want to create something that is different and unique. One of the things that makes [sampling] hip is when you’re making a new little piece of music that didn’t exist before. I am careful about how I do it, but I don’t know how far you go, or what my own rules are; it’s just a feeling. I’ve been doing more remixing lately, and I do find it more challenging, because it’s more challenging to remix music that’s finished than it is when I’m going in and I’m chopping stuff up beforehand. But all that being said, I got into this from the examples before me. I met Jeff Parker on MySpace because we both had sampled the same Joe Henderson track [laughs].

We’re still uncovering what’s possible with making music with technology, and to me, that’s just fascinating. We’re just still scratching the surface of what’s possible with creating and recording. We’ve only dealt with recorded music for what, 120 years? It’s really still fresh and new. And so, to me, it’s about discovery, experimentation, and trial and error.

It makes me think of all the master recordings that were lost in that studio fire and how we won’t get to hear them. Like on some of those jazz records from the 40s, you can’t even hear the bass because apparently audio output technology wasn’t nearly as advanced as recording technology was.

Makaya McCraven: I love those old recordings. There’s something nostalgic about them. I was so inspired by Blue Note, coming up from the ground level before they were even a label. I’ve been building home studios for the last 15 years, getting my whole thing together. And I look at Rudy Van Gelder, who had a recording studio in his mother’s living room. He had a day job as an optometrist or whatever. And Blue Note was over here doing recordings in the living room, creating this legendary catalog that would change the world — it’s a very early example of a small independent label that grew into this really massive legacy label. There’s a kind of kinship with home recording, or that kind of guerrilla recording. There are a lot of live recordings that Blue Note was doing back then, and that’s kind of how I got my start, in a way, doing live recordings or recording in nontraditional locations, or making my own studio and producing in my own way. That was inspiration that I caught over some time, investigating Blue Note and seeing some parallels there.

You described this record as wanting people to learn from it and also just as something to for people to “vibe to.” When you’re working on a remix album like this as opposed to your own compositions, or for a live show, is accessibility or “listenability” something that’s on your mind?

Makaya McCraven: I think about that a little bit, but in general, I’m not trying to make my music accessible for commercial viability. But I do like my music to be enjoyed by a lot of people, including myself. I make records to my ear of what I’m vibing to — I want to know I did my best job of finishing this track. So I do think about [accessibility] a bit. One of the things about making records, versus the live show, is that I make my records in a different way than I put together a show. In a show, the accessibility factor that I want to present to the people is energy and motion, vulnerability and honesty in a space where we can have a transformative experience together that’s less focused around the notes.

When I make records, I’m much more thoughtful about the pace. I like more down-tempo grooves and things that I feel like people can sit back and vibe to, because I find that listening to music in that environment is different than a live show. So here, I’m working with this historical stuff and bringing it into a more contemporary space. I want to have strong grooves and melodies that people can hear and might stay with them, or have strong thematic development, to keep a nice pace to the music and to the record, to bring the listener in and try to piece the whole thing together as a compelling narrative and experience, hopefully in many different contexts. Whether you want to sit down and do a proper listening experience or if you just like to have the record on and accompanying you through different parts of your day. If you’re using it for emotional support, if you’re sad, or you just feel like dancing it out. I hope that my music is there for people to consume, and they can get something out of it. And then when we’re at the live space, then it’s like, all bets are off.

You’ve mentioned that this record is your way of serving tradition while tracing the connections forward. In what ways do you see jazz as a continuum, and is it different from other music and genres?

Makaya McCraven: You know, with jazz — to use the term, which I find wholly insufficient to describe the phenomenon of what we’re dealing with — I think of it as broader than a genre. In the continuum of this music, it has always integrated with all styles it comes in contact with. Instead of [discussing] just the style or the idiom of jazz, we could talk about it in terms of stylistic periods of jazz music, like the swing beat versus straight eighth music, or non-idiomatic improvisation, where it’s going to be completely void of familiar sounds; to fusion to bossa nova, which at one point was the new thing but now is part of traditional jazz; from Miles to Mingus to Duke Ellington. Jazz is a box that holds them here, and then there are racial implications and all the other stuff, but even just that box [is insufficient], because the music has been so expansive and it’s touched so many things.

Even when we’re talking about mixing jazz and hip-hop, you know, I don’t think I’m reinventing the wheel in any sort of way here. It’s not my goal — I’m just doing my thing. But Miles was mixing jazz and hip-hop. Jazz and hip-hop was mixed in the 70s, when [hip-hop] was being birthed. I think even concepts around sampling fit within the tradition of jazz: we have vocabulary, we learn the same outros and intros and tags and turnarounds, and we borrow ideas; you might take the [chord] changes from a jazz standard and write a whole other song on top of it. The recurring forms of jazz are loops, in a sense. There are a lot of ways that we’re borrowing and recontextualizing ideas, where every type of music you might come across is fair game to learn from.

The recurring forms of jazz are loops, in a sense.

I think of myself in this continuum as a musician, and you’re hearing the music of Makaya McCraven. I’m in pursuit of mastery of my instrument, and within this broad understanding of what this lineage is, the best I have is looking towards the elders I have access to for a little bit of wisdom and knowledge, and then doing [my] own thing. Making this record made me think a lot about a lot of stuff. I mean, one is how young the musicians who were innovating this music were. Herbie and Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter, and all these guys when they were going through the Jazz Messengers band were maybe 21 years old, but I was considered a young lion until I was like 34 or 35 years old [laughs]. And so I’m really excited that young people are still making this music, and that there are young people engaging with it. Part of doing remixes and crossing these boundaries is, for me, acknowledging that innovation in this music is a young person’s game. I feel like that kind of got lost in our broader societal dealings with the music, because we are looking to the elders for wisdom. We want to learn from these masters, but at the same time, I think the heartbeat of it is always going to rely on young musicians and people who don’t have to be like, “Oh, I need to learn the idiom of jazz, exactly.” Rather, it’s like, “What can I glean from the spirit of this music? What was the intent of the musicians that were innovating in this, and how do I learn that and take a piece of that?”

Part of doing remixes and crossing these boundaries is, for me, acknowledging that innovation in this music is a young person’s game.

Miles Davis was such an inspiration to me because he always pushed up against [being boxed in], as did Herbie and Wayne Shorter. These guys wrote the rules for themselves. My goals are, like I said, to try to reach mastery of my craft as a player, composer, producer, multi-instrument, or whatever it is. It’s about personal growth and being able to play with an improvising spirit, but also being able to just play music. I think if we’re playing at a high level, and we’re trained, and we’re communicating, then I’d like to be able to play with anybody in any context. It’s not really about genre, but to me, that is the spirit of the jazz musician and creative: we’re here as students of music, and then as vessels to express that in a very open manner where we will communicate with different musicians, but we also have our culture of how we play. Everything is kind of possible.

Speaking of young musicians, you have Joel Ross on this record who’s only 24, right?

Makaya McCraven: I was on tour with Marquis [Hill] a few years ago, and he called Joel to play. I was like, “Joel, man, you sound amazing. When did I meet you? I can’t even remember when we met and you’re 21 years old.” And he was like, “Oh, I was 15 and you came in and taught a master class at my high school.” I was like, “Oh, I’m so old now” [laughs]. It’s inspiring to see not only how talented he’s become, but then seeing him get signed to Blue Note and have that opportunity helped me even want to have the conversation with Blue Note [about this record].

All the people I called are part of my sprawling musical family.

You brought these other musicians into the process to record additional material that was worked into each song. It feels particularly fitting to have Art Blakey’s voice highlighted on “Frank’s Tune,” the drummer who brought so many musicians together. Can you talk about these musicians and what they bring into these tracks?

Makaya McCraven: They brought so much. I’ll start with Jeff Parker, who, along with being such a fabulous musician and creative genius, is just a great friend and a good person to bounce ideas off of — somebody who’s always checked in and helped steer me in a couple directions as I worked on this album. And he was really helpful in that sense, especially working through the pandemic, doing a lot of stuff over the phone. Once things opened up a little bit more, we started doing some in-person sessions, and it was a huge moment when Marquis, Junius Paul, Matt Gold, Greg Ward, and De’Sean Jones started to come to my studio. With the pandemic, I didn’t realize how much I missed and needed some camaraderie and other people’s ideas and inspiration. It really helped everything open up. All the people I called are part of my sprawling musical family. It was important to me to have trusted people there that were each going to bring something of themselves to the record. This is also a great opportunity for me, to feel like I can give this platform to the people that I’m working with and say, “Hey, look guys, we’re making a record on Blue Note! Cool, right?” [laughs] That’s something I’m proud of that I can do for the guys and do for Chicago.

— — — —

Connect to Makaya McCraven on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Nolis Anderson

:: Stream Makaya McCraven ::