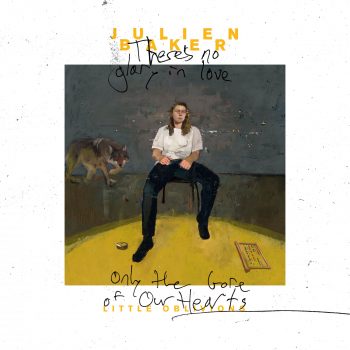

Julien Baker dives into the depths of herself and her breathtaking third album ‘Little Oblivions’ in an intimate discussion of art, honesty, empathy, self-love, and acceptance.

Stream: “Hardline” – Julien Baker

If my music only does one thing, then I hope it makes people empowered to go through that process – empowered to look honestly at themselves; not judgmentally, but honestly – and to use that as an exercise for empathy.

Emotionally impassioned and unapologetically honest, Julien Baker’s music is an intimate, intense outpouring of the soul.

The Nashville-based singer/songwriter reached a new pinnacle of commercial success with her critically-acclaimed third solo LP Little Oblivions, released February 26 via Matador Records. Described by her publicity team as an “unflinching autobiography,” the dynamic, stunning, and stirring full-band album takes listeners on a compelling journey through the 25-year-old’s most vulnerable depths. In 43 achingly visceral minutes, Baker explores addiction and the caverns of her own health and mental state, organized religion and in particular, her Christian upbringing, faith and spirituality, self-hate and self-love, nihilism, cynicism, and much more. Captivating, confessional lyrics find her breaking herself down and, at times, building herself back up again – but there is no mistaking the darkness permeating throughout Little Oblivions, just as there is no denying the record’s irresistibly catchy melodies and cathartic emotional upheavals.

Shell of an engine, unexplained

Burst to fire engulfed in flames

Breathing exhaust, a heatwave mirage

Nothing to lose ’til everything’s really gone

It’s worse than death, than life compressed

To fill a page in the Sunday paper

I had the shuddering thought

“This was gonna make me late for work”

Biting a chain, free like a lame

Oh, can you be healed?

Scratch my knees on the gravel

Say it’s all part of the deal

Covered in scars a canyon deep

It’s not like what I thought it’d be

The gruesome beauty of your face in everyone I meet

I was on a long spiral down

Before I make it to the ground

I’ll wrap Orion’s belt around my neck

And kick the chair out

On a long spiral down

Before I make it to the ground

I’ll wrap Orion’s belt around my neck

And kick the chair out…

– “Heatwave,” Julien Baker

In addition to hitting the top 40 on the Billboard 200 Albums chart, Little Oblivions went #1 on the Alternative Album, Independent Album, Vinyl Sales, and Americana/Folk charts; the album’s lead single “Faith Healer” also peaked in the top 15 of Billboard’s Triple A charts, and was the #1 most added song at radio for a time.

While all of this gives Julien Baker many reasons to celebrate, she doesn’t want to talk about numbers, chart positions, or the album’s “buzzwords,” and she definitely doesn’t want us to think too much of them, either; popularity and “success” have never been a key part of her longterm itinerary, nor do they factor into her identity as a songwriter or a musician.

“It’s difficult for me to think about how much the integrity of my songwriting has to do with the success of any one song,” Baker says, “when I’ve been releasing records for several years and understand the machinations of how a press cycle works, and how people are motivated by buzzwords or by certain qualities that they imbue the artist with in their head… There’s so many others there’s so many power structures at work in the musical realm. I’m trying to be transparent as much as I can, and those are real things I think about.”

I feel like the work that songwriters and poets do is… trying to find revelations, not through this gift of artistic genius that struck me like a lightning bolt, but through repetitive investigation of the soul, of our feelings, of how we think of ourselves in the world.

An “Artist” in the truest sense of the word, Baker holds honesty in high regard when it comes to her art.

Her uncompromising music is a deeply personal experience, and it’s important that the substance of her work is conveyed to her audience. “This record is candid and open and transparent, but it’s very deliberate,” she explains. “These are songs that I’ve sat and played for hours and hours and hours and tried sheets of lyrics with… I genuinely did the best that I could to make this record, and I put so much of myself into it.”

For Baker, music – and therefore, Little Oblivions – is a conversation; it’s a dialogue she’s having with herself, and with those who press play.

“It’s taken me a long time to recognize that I think of music as communication and not as exposition, and the reason why I think I arrived at that understanding is because songwriting for me is about better knowing the self, but also in many ways, it is like a plea to be understood. At least for me, it is maybe the most fundamental need that I have, to feel understood… I don’t want to be a person who harps on God all the time, because that’s been such a huge theme in my music, and it’s honestly exhausting to unfold my personal trajectory with religion over and over again, but I will say, I think growing up religious gives you this idea that secrets are an impediment to being known and forgiven, and that’s a really toxic way to think about it, when you think about it in a punitive sense, but I don’t know. It’s like, what are we actually doing when we confess something to each other? As much as I don’t want to call this confessional, because I feel like a lot of female artists get slated as ‘confessional’ because they’re just disclosing emotions, and that’s not really a confession.”

“I do think that literally, this is a very confessional record, because I am telling the listener about stuff I’m ashamed of and ways that I’ve failed myself and others. Confessional music is scary because it seems like it’s going to need to be met with punishment. I feel like the purpose of confessing is to make the damaged parts of yourself known to the community that can help you. It’s not to put yourself on display so that you can get burned at the stake…”

“I feel like every record that I make is me trying to be like, ‘No, you don’t understand.’ Not telling people that they don’t understand, but trying to further evaluate myself in every record. I don’t want to say things that I don’t mean. That sounds like such a simple sentence, but sometimes we say things we don’t mean to avoid conflict or to flatter another person or put them at ease, or to spare them pain, or we say things we don’t mean because we want to be accepted or we want to be non-confrontational. I say things I don’t mean all the time, and then if I’m gonna do music, that feels like the one place I should say the things I actually mean.”

Julien Baker contains multitudes – and in Little Oblivions, she’s opened herself, and her many facets, up to the world.

From the enthralling, dramatic rush of fervor and feeling in opening songs “Hardline” and “Heatwave,” to the record’s hauntingly bittersweet closer “Ziptie” (one of Baker’s personal favorites), Little Oblivions shines a light not only on Baker’s own experiences, but more generally on some of life’s hardest journeys and darkest emotions.

“The expression Little Oblivions is about trying to construct little artificial temporary escapes from our own reality because reality is extremely painful,” Baker says. “People can do that in obvious ways through the distractions of drugs or relationships or alcohol or whatever, but you can also do that in so many other covert ways, in obsessive compulsive behaviors or in the way that you handle your anger or in physical violence… There’s so many ways that we try to alienate and suppress and deny our feelings and seek instead the temporary relief of non-being.”

There’s so many convoluted ways that human beings try to alleviate themselves from feeling.

The irony of Little Oblivions is that, in exploring these ways in which we keep ourselves from feeling, Julien Baker provides us with a vessel through which to experience a sweeping, vast array of emotion – some we can give names to, and others of which simply must be experienced in order to be understood.

Limping like a prodigal son

Someone got my head in the slums

Everything I do makes it worse

Human nature, call it a curse

Tired of collecting my scars

And stories at the parties and bars

Tryna find a reason to fight

Someone’s got my head in a zip tie

Oh, good God, when you gonna call it off?

Climb down off of the cross and change your mind?

Catch me on the enemy line

Hocking all the gold in my teeth

Oh, I was disappointed to find out how much

Everybody looks like me

– “Ziptie,” Julien Baker

The true beauty of Little Oblivions is that it is a record of healing.

Baker’s breathtaking third LP is so full of exposed pain and anguish, but also compassion, patience, recovery, open-mindedness, self-discovery, and ultimately, inner strength and self-love. Yes, these are buzzwords – but they speak to the greater story arc of self-affirmation and acceptance that informs, and in some ways, guides these twelve songs.

“This is going to sound very therapy jargon,” Baker advises, “but I think that having compassion for yourself and practicing that makes you a more empathetic and more forgiving person. I really think it does. But it comes at the cost of the pain of looking into the ugliest parts of yourself. I think if you can look at the ugliest and the darkest and the worst things that you’ve ever done or said, or thought, and still care for your own happiness and for your own fulfillment, then it makes it so much easier for you to practice that with other people. I don’t want to use a hashtag, a buzzword, phrase like “self-love is the answer” or whatever. Sometimes when things get oversimplified, I think they lose their salience because they become trite, and then people don’t take them seriously. It took two years of me being turned off by the word self-compassion before I finally had compassion enough for myself to use it as a resource for compassion towards others. And if my music only does one thing, then I hope it makes people empowered to go through that process – empowered to look honestly at themselves; not judgmentally, but honestly – and to use that as an exercise for empathy. That’s what I truly want.”

Speaking with Atwood Magazine earlier this year, Julien Baker dove into the deep (and sometimes dark) depths of herself and Little Oblivions in a discussion about art and honesty, identity and personal growth, empathy, and self-acceptance. Read our full interview below, and be sure to give Little Oblivions your full and undivided attention the next time you press play.

Julien Baker spilled her soul in bringing this music to life; the least we could do is listen to what she has to say.

I felt like I was trying so hard to make something that was capital “A” art and maybe I succeeded, maybe I failed; art is subjective, I don’t know, but this record felt a lot more like I just wanted to make decisions that were intuitive, and to put the songs I liked best on the record and to make the noises that I thought sounded good.

— —

:: stream/purchase Little Oblivions here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH JULIEN BAKER

Atwood Magazine: Julien, I can't in good faith start any conversation without asking how you’ve been doing over this pandemic; how are you, your family, and loved ones?

Julien Baker: Fortunately, my family is safe and they, my mom and stepdad, had COVID, I don’t think my dad and stepmom ever had it… we’ve all been okay. I live with several roommates, and I’ve actually been super grateful for being in a communal living situation instead of living alone, because you have all these other people around to sort of process what’s happening. So I’ve been okay, which I know I’m blessed for, considering everything, and all the havoc it’s wrought on our world. Thank you for asking.

We’re speaking at the tail end of Women's History Month, and I thought it might be timely to ask, what kind of space do you want to carve out for yourself as a woman in this industry?

Julien Baker: That’s a big question, and I think it’s difficult for me to talk about being a woman and being a queer person separately, because I feel like they mutually influence each other, both of those things, like how I see myself as a woman who is not… Who doesn’t necessarily present as in the conventional feminine ideal, and also how I see myself as a woman after having been surrounded by males in disproportionately male spaces for basically the entire time I was becoming a musician. And I think I’ve been just re-evaluating how I think of myself in this world and how I allow… I think it was very popular when I… It was a popular ideology in the scene I was in, and when I grew up for me to… For women to normalize themselves by assimilating or in a way of taking up space as in… I don’t know, but it’s very funny, ’cause it’s like the scene I was assimilating myself into wasn’t necessarily the heteronormative straight culture scene, it’s like I gave myself a mohawk, and I dressed really weird, and I was in a super aggressive band, and I thought of those things as radical.

But I didn’t do a lot of acknowledging myself as still being socialized, female, and how that comes down to just like ways that you think of your body, in the world, ways that you think of your personhood, and especially as it kinda mutually influences my thoughts on my own queerness, too, because it’s like, “What does it mean to be a woman,” right? People witness me, I’m like… I’m not the most fem, but I’m straight passing, I don’t… So I walk through the world with it regarding me as a cis woman, and that influences my experiences, but also it’s like I don’t wholly… I don’t know what I’m identifying with, specifically as a woman outside of how I’ve been socialized, because I think it is yet a construct to try to define what it is to be a woman in the world.

Thank you. You've been actively releasing music for six years now; have you taken away any lessons from your time in the music industry?

Julien Baker: So many. I think I have learned a lot about how to be compassionate. I’ve learned how to be hopefully a little bit more compassionate with myself. I’ve learned importantly that humility and self-loathing are different. I think, for me, one of the challenges is existing in a position of elevated visibility and feeling highly critical of the mistakes I make, because they are witnessed by so many (or what feels like so many to me), even though in the scheme of things, it’s changed the way that I interact with art and music – I think in some ways for the better, and some ways for the worst. I think about the music that I make more now as contributing to a discourse, and less as some way that I’m trying to establish and re-affirm my own identity, you know? It’s such a minuscule piece of myself and my life, and the reason why I make it has to be because I’m willing to be a part of the conversation, not because I am hungry for recognition and validation. But that’s just a thing that everybody has to learn about, whatever it is they do in their life to try to be recognized and validated.

I think about the music that I make more now as contributing to a discourse, and less as some way that I’m trying to establish and re-affirm my own identity.

That's a good jumping off point to go into your music: Little Oblivions has been resoundingly praised as your best album to date. I know it's a little unconventional to start an interview off this way, but do you agree?

Julien Baker: I don’t know. I’m sure that every artist feels that the record they have just released is their best work, and I would hope that I continue to feel that way, even if nobody else feels that way, because I think it is the task of an artist to continue challenging themselves so that they don’t stagnate, and they create something new and something alive, but… I’m never been happy completely with a piece of art.

There’s never been a moment where I’m like, “Yeah, I’m pretty happy with that.” Like, I think I just get things to a reasonable place where I’m like, “Okay, I can suspend my neurosis for like… ” [chuckle] And understand that this is probably in a good place, but we’ll see. I feel proud of this record, and I’m trying to let myself feel proud. I think at first when I was talking to people about this record, I was trying to make this clear distinction between my previous two records, Turn Out the Lights and Sprained Ankle, and this one, because they’re so sonically different and also because my life has just changed so much. But I’m trying to let myself appreciate all of the art that I have made by myself and with other bands for what it gave to me then… Wow, this is the most like [chuckle] Zen, like all of these answers…. I don’t know, I feel bad for giving you like, boring “Zen” answers.

They're not boring at all! I respect how your relationship with your own art changes over time. What's your relationship with this album like now, a month from its release?

Julien Baker: … I don’t know. It feels relieving. I mean, and I understand… This is not me being cynical, it’s just me being realistic for my own mental health and for the limiting of my own ego, but I understand that there is a difference between the music publications and outlets that cover my music and how people at large feel about my music. I listen to the songs now and I feel proud of myself for putting out something that felt risky to me, that felt like a lot of change because I’m a person who is slow to change. I hate to admit that about myself, but I’m very… It takes me a long time, like it takes me a long time to like new bands or like new styles of music that other people just immediately click with. And so like… I’m proud of myself for doing this, but I also feel super relieved, ’cause I’m not… Now I’ve been doing interviews and stuff about the lyrical content and just about my life through the record, and I don’t have to be apprehensive about those things anymore, you know? I think I had so much fear about disclosing them to the public, and now I’m a lot more at peace with being seen in that way, I guess.

This record was described by your own team as an ''unflinching autobiography.'' Can you share a little bit about the story behind Little Oblivions, and maybe even the title itself?

Julien Baker: Sure. So the title is a reference to one of the songs, “Bloodshot” and it’s… That entire song, but specifically the expression Little Oblivions is about trying to construct little artificial temporary escapes from our own reality because reality is extremely painful. People can do that in obvious ways through the distractions of drugs or relationships or alcohol or whatever, but you can also do that in so many other covert ways, in obsessive compulsive behaviors or in the way that you handle your anger or in physical violence, there’s so many ways that we try to alienate and suppress and deny our feelings and seek instead the temporary relief of non-being. That’s why it’s like, so I have anxiety, so I go run or physically exert myself until I can’t feel anything, but some people like an avoidance behavior could also be just going to sleep, like people that go through a depressive episode and just wanna sleep, or people that abuse substances because they wanna knock themselves out and turn off their brain. It’s like I’ve been all three of those people, and I spend a lot of time thinking about why… When I had fallen into this sort of cyclical self-destructive cycle, I spent a lot of time wondering why I kept doing it and what was so attractive about the momentary relief from a painful present. Yeah, so and that’s what this record is about.

It's so interesting, the way you talked about some of these different things. Obviously, there's a big difference between substance abuse and going for a run. But they kind of all fall under the category of Little Oblivions, and I guess we can approach these things as negatives or detriments to our health, and certainly some of them are, but it's all about how you look at them, because some of these same things that fall under this category could be ''positive coping mechanisms'' – a different album title.

Julien Baker: Sure, yeah. Positive coping mechanisms, I think though like what’s different about… If you wanna use the example of running, it’s like I could… Especially when I was on tour in 2017 and ’18, I would run compulsively so much that it physically hurt me and I had all of these knee and ankle and back muscle injuries, and it was like I was straight up in a lot of pain, but now it’s like you can kind of… It’s like that there’s a Circa Survive song that says this, but I think it’s just like an expression, but the difference between medicine and poison is the dose. So it’s like now, I try to make sure that running is something I do, that when I’m going running, I am doing so because I want to, not because I have to, I need to, but you can do that with anything else. It’s like, yeah, you can sort of absolve yourself from feeling through the denial that comes with an intense attachment to a religious belief system, that’s another way. There’s so many convoluted ways that human beings try to alleviate themselves from feeling.

It sounds like the last few years and this music gave you lots of perspective. Did you have a clear vision of this album's arc before you went into the studio, or did it change over the course of recording?

Julien Baker: I started in January 2019 and recorded the record over the course of the following year, and I made like 20 something demos in January and I had all of this material, and then I only ended up using a handful of songs that I’ve been working on previously because I was writing to process everything that was happening to me throughout that year, and so it’s… I don’t even know if I would say that I had a clear vision about this record, even when it was done. And that’s not out of disinterest or apathy for the music that I was making, it’s just that on my sophomore record, I tried so hard to have a clear planned out arc and a narrative and all these motifs and all the very meticulous planning went into it, and with this one, I felt like I was trying too hard. I felt like I was trying so hard to make something that was capital “A” art and maybe I succeeded, maybe I failed; art is subjective, I don’t know, but this record felt a lot more like I just wanted to make decisions that were intuitive, and to put the songs I liked best on the record and to make the noises that I thought sounded good.

Lowercase “a” art.

Julien Baker: So it was lowercase a “art.”

Well, congratulations on hitting number one on the US Folk Charts!

Julien Baker: Whoa I didn’t even know that until right now! That’s cool.

But it's not really your typical folk album, is it? You played a slew of instruments on what ultimately feels like a full-band rock album. What drove your musical decisions?

Julien Baker: Well, I think it’s inevitable and I think healthy for musicians to want to pivot when they’re making a new body of work, and for me, it’s like I find I work well when I impose challenges on myself, so I don’t know that was partially why I wanted to play all the instruments myself, even if I could have found someone more competent, like a really incredible banjo session player, I was like, “No, I think I’ll just play the banjo,” because then I’ll end up sounding clumsy and truer to the music that I listened to as a kid, that was so emotionally impactful for me, but also it’s just like, I don’t know, I wanted to not be… I wanted my music not to be governed by a preconceived notion of where my lane was musically, and I didn’t want that anymore to preclude me from adding drums to the song that I thought needed drums. And for a while, it’s like I wrote minimal music because I felt like that served the song and I liked that process, but then I think just like every artist, I just wanted to change.

It sounds like... And this sounds so pretentious, but I swear, I don't mean it that way, you weren't going from polish, you were really going for truth.

Julien Baker: Yeah, I mean, in a way… Yeah, what “truth is” is such a slippery notion, but I wanted to make something and I think this is actually true of my other records too, it’s like I’m just making something to the best of my ability with the tools I have in front of me right then, and that is a characteristic of music that I really enjoy.

It’s music. I say this a lot, and I don’t wanna repeat myself, but music, to me, is a communication tool. I’ve existed for a long time in the performance sphere, and I think it is easy, especially within a consumer’s context, to relate to music as a form of entertainment that can be consumed, but for me a massive discourse that you’re engaging or not engaging with. And I think when I started to return to thinking of music that way, it took away so much of the pressure to make an immaculate record, to make a record that was universally regarded as great… it’s comforting to know that not everybody is gonna like your stuff, not everybody is even gonna like you.

I think it is easy, especially within a consumer’s context, to relate to music as a form of entertainment that can be consumed, but for me a massive discourse that you’re engaging or not engaging with.

Together with Lucy Dacus and Phoebe Bridgers, you formed boygenius, and released your EP in late 2018. Compared to when you're writing and recording for yourself, what was that collaborative experience like for you?

Julien Baker: It was wonderful, and it’s honestly unlike any other collaborative experience that I’ve had, but I’m starting to think that it might just be that since we had been friends so long and since I have thought… Since I met them years ago, I’ve thought of them both primarily as my friends who are performers and musicians I admire and respect so much, but that I was comfortable enough, it was an intimate enough space for me to feel safe, giving my ideas. I feel like… You would know it ’cause I run my mouth off for 10 minutes at a time and I play music, but I feel like I’m kind of a shy person, and it’s difficult for me to trust people in creative situations. Or to trust myself, I guess. I guess what they gave me as people, and they’re like, “This is friends too, outside of the musical context.”

But I don’t know, helping me trust my own intuition, ’cause I think, again, if you wanna talk about the space that one carves out as a woman, I think all of us recognized that we had been regarded as inferior or less knowledgeable, as a matter, of course, without it being malicious, it was still damaging for us to feel constantly like we knew the least in the room, and I think having the… Being self-possessed and confident enough in the worth of your own ideas and in your own ability is something very valuable that honestly, I feel really proud of. I’m proud that we made that record, that we produced it by ourselves, that we wrote those songs I don’t know. Yeah, it is easier to be… It’s also easier to be sure of yourself when you’re in a band with two of your favorite musicians ever, so I was just like, “Yeah that song, rocks, y’all are awesome.”

Did the positive energy and experience with boygenius have an impact, do you think on your album?

Julien Baker: Oh, for sure, for sure. Yeah, and also they were just there for me as friends while I was going through a lot of change. Yes, the experience of being in boygenius and making the music was a catalyst for me to take my own musical decisions more seriously, but it was also just being around them as people, having them as friends helped me re-prioritize what it even is that I think is important in my career and life.

Thank you for sharing all of that. I understand that in the years in between Turn Out the Lights and Little Oblivions, you not only formed and toured boygenius, but you also went back to school and got your degree. What was that experience like for you?

Julien Baker: It was great. I had always wanted eventually to go back, but it was kind of something that I just kept pushing off and you know, I think I really like school like university, I was horrible. I hated high school because I won’t even get off on how public education sucks, but yeah, I love university ’cause I love just studying texts and learning things and trying to challenge my brain to think about things differently, or in a more discerning way. And I also loved the idea of… I don’t know, I spent almost a whole year not being on a stage, not doing any interviews, not being really on social media, just like listening to my professors talk and turning in papers and walking around campus and drinking really bad coffee, and it helped me think of… It helped me detach from my identity as a performer, being the only possibility for myself I thought could exist. Yeah, I don’t know, I think it did a lot to accomplish something unrelated to music for me.

What was your field of study?

Julien Baker: It just says I have a degree from the College of the Liberal Arts. I changed my major like three times. So basically, I just finished out the degree, I have a degree in something, but it’s mostly English.

I took five literature courses, upper division literature courses at once, and I thought my brain was gonna explode. I took British Literature one and two at the same time, so I was having to read Beowulf and also read Charles Dickens, and I was just like, urgh! But it was fun. Maybe I’m a person who’s a little bit of a masochist because I talk about it being so hard, or I talk about, I don’t know, going on a really difficult steep run, and then I’m like, “Yeah, but I loved it.” I loved it. You know, it gives you self-confidence to see or to watch yourself growing mentally physically, to see yourself accomplish more today than you were able to yesterday. Yeah, I don’t know. Again, very therapy lingo thing but it’s true.

If the opposite of progress is stagnation, or going backwards I'd rather have progress. Going back to your album... For you, is Little Oblivions best understood as a continuation or a re-introduction or something else entirely?

Julien Baker: You know I’m thinking about it like a continuation… or a re-introduction. I’m actually reading a book that’s a sequel right now, I’m reading The Committed and it’s a sequel to this book called The Sympathizer, and I historically… I’m not super big into sequels because almost always, they are like a less thoughtful attempt to follow-up a similar idea, but I love this book and I think it’s really good as a sequel. However, while I respect Viet Thanh Nguyen’s ability to stretch out this narrative in a really thoughtful and un-corny way, I think I would prefer to think of my music as episodic. Instead of Breaking Bad, it’s like Black Mirror.

I know you know what the word episodic means, but I always over-explain things… it’s a part of my obsessive-ness, because I just really wanna make sure people know what I’m talking about, and I’m not just saying nonsense. I like to think of the music that I release episodically; it’s its own arc. Maybe one day when I’m an older, more prolific musician, I’ll be able to see how all these little bodies of work create a catalog that has some sort of arc, but for now, with the last three records, all I can do is just document what’s happening in my brain at that moment.

I think I would prefer to think of my music as episodic. Instead of ‘Breaking Bad’, it’s like ‘Black Mirror’.

Julien Baker: I was sitting down in my apartment and asking myself questions about what I was doing. I was trying to look at my behaviors and say like, “What is it that you’re doing this for? Is there something you’re trying to avoid? What are you trying to get away from right now?” And it was an extremely painful process, but yeah, I just… That’s one of the most brutal songs for me on the record because it is so candid, but also I think it’s fitting that that’s maybe the most heavily… It’s the heaviest arrangement maybe, on the record. Yeah, I don’t know, I needed a place to put my nihilism and cynicism and ask, I was like, “I’ve been singing for years and years and years about how things all eventually get better and everything happens for a reason, and there’s a lesson in all of our failures, but… How true do I think that is right now when I keep making the same mistakes and I don’t see a way to stop it, and I don’t think that it’s teaching me anything, I think it’s just suffering.” [chuckle] Yeah, so that’s what that song is about, it just being like, well, maybe it’s actually just all bad all the time, and there’s not good and bad, there’s just bad, but that’s very… That I hate that I had that feeling, but it’s also worth acknowledging that there was a time in my life where I felt that fatalist about everything.

It's okay for both things to exist, you know; contradiction is just a part of life. You told NME how making this album helped you understand that recovery and self-improvement isn't linear. I was wondering if you could share a little more about that.

Julien Baker: Actually, this makes me think of something that we were talking about, preferring “progress” to “stagnation.” I’ve been thinking a lot about how we as a society or as people define progress. And it’s actually very… I think it can be kind of insidious, it can discourage you from working backwards it can discourage you from doing the very important thing that no one seems to want to tell each other or themselves to do, which is rest. Gosh, I think of the term recovery is like… Yeah, I’ve been in recovery for substance abuse, and I’ve also been in recovery, for tendinitis that made me not able to stand up straight, and the thing that everybody told me to do was to just wait and just stay off of it and just be gentle with yourself. When I was struggling when I had a whole bunch of running injuries, but… Yeah, I don’t know, I think I thought in this very linear sort of way about my experiences with substance abuse because I don’t know, I had gotten sober, the once when I was still quite young, and I saw myself as having these two Jekyll and Hyde signs, there was bad addict Julien and then there was good, new, shiny, new better Julien, but there were so many different things that I wasn’t addressing just because I thought I had made progress in this one area.

And they ended up failing to maintain all these other parts of my mental health, ended up cycling me back into addiction, and then when I was going to therapy and trying to do all these different things to work on myself, and I say this, ’cause I actually, I see this happening to some of my friends as they are going through difficult times in quarantine, the being obsessed with the idea of better. I don’t know, I think it’s really… It can be really damaging to feel like you always need to be progressing or to create this imaginary goal post of what you think better is gonna look like, especially… Does better mean that I work on the problematic parts of myself and I get back together with my partner or does better mean that I get healthy again, or I am able to maintain sobriety so I can tour again, and then everything goes back to normal, and then I continue doing the same thing. It took me a while to understand that better might not look like what I thought it would. And that acceptance is a lot more important to me than constantly propelling yourself towards an imaginary goal that you think is gonna satisfy you, ’cause when you reach it, then you’ll have a new goal, and then when you reach that… I don’t know, it’s just, it’s difficult to try to… I don’t think people will ever be satisfied with that kind of definition of progress.

I think it goes well beyond your music, but if we could also tie it into the music, what role do you feel these ideas of acceptance, of addiction, of recovery, and struggle therein play on this record?

Julien Baker: I think in the midst of writing this record, I didn’t have a ton of acceptance for myself. When I was making it, even up until 2019 when we were finishing it, this record felt very much like self-flagellation for having missed the mark of all my principles that I had been talking about in interviews and to people at shows about and at the merch table and on the Internet, I had been propping up a lot of ideologies that I thought comprised my identity, and I felt like a failure or like a traitor for finding myself struggling with substance abuse again, finding myself failing to be kind, in fact, not just failing to be kind, but doing extremely hurtful things to the people that I love the most. But now that it’s been pushed back a year and I’ve been sitting with these songs for quite a while it’s like, I find it much less of a public self-punishment than much more something I want to release as a testament to how far off track a human being can get and still be worthy and still consider themselves forgivable.

And that’s something I don’t know if I would have said if we had released this record in 2020. But yeah, the more I talk about it, the more it’s like… I don’t know, it’s kind of maddening because it felt like so many of the interviews I did around it earlier, and so much of literally the lyrics on this record are like, “Look, I failed, I failed, I failed. Look how bad I failed.” And it’s kind of bizarre to be praised for just for admitting. It’s not the response that makes sense to me, but it is also in these conversations, I’m recognizing that maybe releasing the admission of those failures out into the world is useful just as a model of how to be honest with others, and also, with yourself. You can be… You were speaking about contradictions, you can be honest with yourself. You can make mistakes and still be a worthy human being, like finding out that my friends can be angry at me and love me at the same time, like wow, amazing. Finding out those things is really important to me, I think.

Are you always the speaker of your songs?

Julien Baker: Let me think. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, I was going through to make sure… But yeah, I don’t and this is something I guess I wanna challenge myself as a songwriter to play with more, but I don’t do well inhabiting a character because I have so much reluctance to speak on anyone’s experience except for my own, because it’s the only one I can hope to accurately or truthfully represent, and even that, it’s like we have our own self-delusions that inhibit us from accurately representing ourselves, but I can get closest with my own feelings and yeah, I don’t know, I do a lot of in my brain, putting myself inside the experience of others to try to understand them, I mean, that’s just the human practice of empathy, but I don’t ever wanna… Like I don’t wanna speak on people’s behalf in that way through the art that I make maybe one day I will, but who knows. We’ll start with second person, second person, I can just kind of observe your person and then we’ll move into separating narrator and author.

It's interesting when you really come to understand that we're hearing you in these songs. I think it makes them all the more an intimate experience from the listener's perspective. Another song that really stuck out to me was “Faith Healer:” “I miss it, how it build the terror and the beauty, and now I see everything in startling intensity... Come put your hands on me, a snake oil dealer, I'll believe you if you make me feel something.” This has become Little Oblivions' most streamed song to date. I'm curious if you could share a bit more about this song and if you have any thoughts on what you attribute to its ''success.''

Julien Baker: It’s difficult for me to think about how much the integrity of my songwriting has to do with the success of any one song when I’ve been releasing records for several years and understand the machinations of how a press cycle works, and how people are motivated by buzzwords or by certain qualities that they imbue the artist with in their head or whatever, and I didn’t even want this to be the first single.

Really?

Julien Baker: Yeah, it wasn’t like a contentious thing, it’s just that everyone except me was like, “No, this should be the single,” and usually when everybody else is telling you that… I just try to listen to people instead of thinking that I’m like a mighty end all be all on stuff. So I don’t know, it’s difficult for me to think about that song being successful because of something that I did to it, when there’s so many others there’s so many power structures at work in the musical realm. I know that’s not a sexy answer, but that’s my… I’m trying to be transparent as much as I can, and those are real things I think about, I’m like, “Man, I don’t even know if it matters which single came out first or if people… ” But there’s no accurate way to gauge how people really feel about the record, but… Yeah, I don’t know the song, it was gratifying for me to make it as a… It was not a problem song but I originally attracted a different time signature and I really wasn’t happy with the demo and I almost didn’t put it on the record, and then we re-worked the whole thing and put it out. And then I don’t know people ended up liking it, so I guess that’s gratifying to me because that also is an experience that helps me understand my work as a craft instead of thinking…

I was actually talking to Julie Height and McKinsey on the day that my record came out about this, but the idea of something being raw means that there has been no preparation put into it, it’s crude, crude is a synonym for raw. And so I feel like when people called my music “raw,” that was kind and maybe it was at that time because I was a kid, and so everything was… There was an immediacy to all the emotions, but this record is candid and open and transparent, but it’s very deliberate, it’s like these are songs that I’ve sat and played for hours and hours and hours and tried sheets of lyrics with and stuff, and the fact that people actually do like the song “Faith Healer” makes me feel like… I don’t know, sometimes I feel like my job is not a real job and everybody… To a person is like, “Oh, stop. Everybody has a different experience.”

But really, when I drive by people in Nashville doing contractor work, it’s honestly hard for me to think of this job as work in the same way because it’s not physically demanding or because it doesn’t have an immediate product, but something like this helps me think, like I could have given up on that song or I could have been lazy and put out a bad song, but I genuinely did the best that I could to make this record. And I put so much of myself into it, and I don’t know, maybe that balances how I feel about the artificiality of my recognition because of whatever Spotify playlists or something.

The entire basis for this conversation that we're having today.

Julien Baker: Yes, I’m sorry, that’s not supposed to be critiquing you or your work, or Grandstand’s work or Matador’s work. It’s just something… It’s like, my eternal self-critic is so crafty, I cannot let myself have anything, it’s like, “Well, you know that you’re only successful because…“

Well, I appreciate your honesty with me, and it's interesting as a music lover and as a songwriter myself to hear that you re-worked these lyrics into a new song. Just knowing how hard it can be to take something that you wrench from yourself and then to have to touch it after you put it down for the first time.

Julien Baker: Exactly. I mean, it’s… I don’t know, it’s a little bit like… There’s gonna be some chemist at a chemical plant be like, “It’s nothing like chemistry.” But it is a little bit like chemistry!

It's emotional chemistry.

Julien Baker: It’s emotional chemistry! In chemistry you have formulas and values and stuff, but there wasn’t always that. Somebody had to discover the properties of elements by doing experiments with them that could be very dangerous. And they had to figure out the properties of how chemicals react with each other, blindly… You know what I mean? And so it’s like in that way, I feel like the work that songwriters and poets do is… Even though knowing that everybody’s mind is a different… I don’t know, is a different terrain, and you’re working with people’s thoughts and feelings and emotions that aren’t the same as like the periodic table of the elements is always the same, but trying to find revelations, not through this gift of artistic genius that struck me like a lightning bolt, but through repetitive investigation of the soul, of our feelings, of how we think of ourselves in the world. What behaviors in relationships or in life are productive and healthy? Which ones are not healthy? And it’s just like, that to me, is a more noble pursuit than trying to defend the fact that I am innately more talented or more sensitive and more artistic. I just do this a lot. You know what I mean? Chemists get good at chemistry because they just go to a lot of chemistry school.

It sounds like there's a push and pull for you between lowercase and capital ''a'' art.

Julien Baker: There definitely is. And it comes down to, it’s like, I can’t pretend to exist in a reality that has not been formed yet. I can work with the tools that are available to me now. I was born in the United States and raised and socialized in a context where pretty much everything is commodified. So I can have a lot of like lofty ideas about art, like capital “a” Art, and how it should and shouldn’t be commodified, but in order to continue to have that conversation, it’s like, I don’t know, there’s always this, “How much are you willing to acquiesce in order to have a seat at the table?” And for me, I think that used to be more, especially when I was a young kid, and I hadn’t… I keep saying young kid, I don’t know, I was 19.

I was 19 when I got signed for the release of ‘Sprained Ankle.’ I was nominally, factually a teenager. I wasn’t thinking about this stuff. I was just like, “Cool, yeah, somebody please give me money to play music ’cause it’s the only thing on earth I care about.” And now it’s like, I don’t know, I can choose to relegate my power as an example, or I can choose to try to operate as ethically as I can within an unethical structure to make change within that structure now that I’ve been given a seat at the table. And I go back and forth on that every day. Some days I just wanna put my music up on Bandcamp for free, and go fuck off and teach English at a community college. Like, I don’t know, it’s just like everything, it’s in perpetual discourse, we’re figuring it out, we’re negotiating all of us together in this weird thing, so…

One thing I found in listening to this album over and over again was how unrelentingly honest its lyrics feel – and you validated some of that earlier. Not to say that Turn Out the Lights and Sprained Ankle weren't honest records; I realize that this kind of vulnerability takes its toll. Can you speak to why it's important for you to be so forthright on your records?

Julien Baker: So it’s taken me a long time to recognize that I think of music as communication and not as exposition, and the reason why I think I arrived at that understanding is because music is about, specifically songwriting for me is about better knowing the self, but also in many ways, it is like a plea to be understood. At least for me, it is maybe the most fundamental need that I have, to feel understood. I think that’s true for a lot of people. Some people don’t need to feel understood and they can make weird crazy avant-garde music because they are using music for a different a purpose to establish their own worthiness and be like, I get to… You can be weird if you want to. I’m an example, I’m gonna be weird whether you like it or not.

I am not so oppositional with my music, I just desperately want to be understood, and I think that that comes from this… It would be, I don’t wanna be a person who harps on God all the time because that’s been such a huge theme in my music, and it’s honestly exhausting to unfold my personal trajectory with religion over and over again, but I will say, I think growing up religious gives you this idea that secrets are an impediment to being known and forgiven, and that’s a really toxic way to think about it, when you think about it in a punitive sense, but I don’t know. It’s like, what are we actually doing when we confess something to each other, as much as I don’t wanna call this like confessional, because I feel like a lot of female artists get slated as confessional because they’re just disclosing emotions and that’s not really a confession.

I do think that literally, this is a very confessional record, because I am telling the listener about stuff I’m ashamed of and ways that I’ve failed myself and others. And I don’t know, I have been thinking a lot about the idea of confessing and why we create a structure where we need to confess in organized religion or… In the law even, I’m like, man, being… Confessional music is scary because it seems like it’s going to need to be met with punishment. Honestly it’s like… I don’t know, I feel like the purpose of confessing is to make the damaged parts of yourself known to the community that can help you. It’s not to put yourself on display so that you can get burned at the stake, or you can get I don’t know, locked in prison for several decades to make everybody around you feel like there’s a sense of justice in this world even though that actually creates more recidivism than… I wouldn’t even get to talking about prisons, but…

Yeah, I just… I feel like every record that I make is me trying to be like, “No, you don’t understand.” Not telling people that they don’t understand, but trying to further evaluate myself in every record, so that the things I say to people… I don’t wanna say things that I don’t mean. That sounds like such a simple sentence, but sometimes we say things we don’t mean to avoid conflict or to flatter another person or put them at ease, or to spare them pain, or we say things we don’t mean because we wanna be accepted or we wanna be non-confrontational. I say things I don’t mean all the time, and then if I’m gonna do music, that feels like the one place I should say the things I actually mean.

I say things I don’t mean all the time, and then if I’m gonna do music, that feels like the one place I should say the things I actually mean.

What you just said is really powerful, and quite frankly, I think it's really admirable. In line with the imagery of Little Oblivions when you talked earlier about the overarching album concept. I feel like each of these 12 songs has its own sort of tiny upheaval, their own 'Little Oblivion' if you will. You've talked about music as communication, do you also consider it a form of therapy?

Julien Baker: For me, yes. It is therapeutic. I have like the way we typically imagine therapy is happening like in a group setting or between one therapist and a client. No, because when I’m writing music, and this was true, I remember getting in an emotional fight with my high school band because I brought the song to practice that was super sad and doomy and then my friends, were all just like, “Okay, so then what if we put a bridge,” and I was like, “I’m trying to tell you about my feelings in this song, and you’re talking about like, “Oh, you should kick your distortion on and we should put a bridge in there,” and I’m like, “No. These are real feelings.” Oftentimes, it’s like the work that you’re doing is more just like journaling to evaluate later. I don’t think that it’s necessarily like writing a song helps me process difficult emotions in that… I don’t know, it just takes time. There is not another person critiquing my thoughts and my lyrics, and the motivations behind the feelings I’m writing about that person has to be myself. So I’ve written songs that well I don’t know, maybe they’re okay songs, they come from a very skewed place.

Especially a lot of the stuff on Sprained Ankle because that was like there was a bunch of classic like, “why don’t you like me back” heartbreak songs and it’s just really like, I don’t know, it’s really self-serving, but it’s okay for me to look back at those and say, “Wow, what a narcissistic way to imagine a relationship.” There are little documents and part of I don’t know, you gotta have a high tolerance for humiliation if you’re gonna be a musician for any length of time, think about bands looking back on their first record they ever put out and be like, “Yikes,” or maybe looking back on a mid-career record and being like, “I don’t know what I was thinking when I wrote that.” You had to do it. And the thing that’s valuable about music is making, especially if you’re a musician who has like a longer catalog, you’re making your process of growth public, and you’re willing to keep editing and adding and changing, so yeah.

This is an aside, but I've always wondered how a band like The Killers feel or the first song of their first album is their most popular song, and they've been making songs for two decades now, and they're like, ''We have so much more of a story to tell,'' and there's so much more for them to talk about, and they've been doing so much over this time, but everyone still wants ''Mr. Brightside.''

Julien Baker: Dude Yeah, I wonder about that a lot too. I mean, the thing with the Killers is they rock, and they’re such a great band, but they’ve gone through such a crazy arc and like I think more people are aware of their songs besides “Mr. Brightside” it’s just like so everybody, it feels like in the United States, at least, knows that fucking song it’s like there’s still a massive amount of people that are invested in them as an artist and as a band, myself included, ‘Battle Born’ unpopular opinion Battle Born is my favorite Killer’s record – that shit could be a Springsteen record!

Anyway, enough about the Killers (no, never enough!), but yeah, that’s gotta be frustrating. I also wonder about, I know I’m going to reach a point in my career because it happens to all musicians where people are like, “That girl ran out of good ideas,” and I’m like… That is why I don’t love to shit on bands, I never have… I feel like all my friends love to be like, “Oh, you heard this band this new song sucks,” and it’s like… I don’t know, I wonder about those musicians as people and about them being like having all this pressure around them late in their career and releasing something that’s really important to them and that they put a lot of work into, and then having people straight up and make fun of it and call it like phony. I’m like, “Oh no, it’s okay.” [chuckle]

That's the empath in you.

Julien Baker: Yeah, it’s strong. The empath is strong.

''Catch me on the enemy line, hocking all the gold in my teeth, I was disappointed to find out how much everybody looks like me.'' We talked about how you started the album. Why did you wanna end the album in this way with ''Ziptie''?

Julien Baker: Because after feeling that anger and writing, starting with the chorus, that’s like, when will you change your mind and give up on humanity at God, but it’s like after… Immediately after having that thought and understanding it, it makes sense to have that thought. It’s perfectly reasonable, and I needed to express it. I thought about… I don’t know, obviously, this is using the imagery of somebody being literally at war, like walking up to, in a very like World War II, trench warfare where there’s actual lines and everything isn’t, I don’t know, on the Internet and propaganda. But yeah, it’s just like being in need, cooperating with someone that you tell other people is your enemy, so that you can meet your needs, and as you’re doing this exchange where I’m like theoretically selling my gold teeth to people I’m supposed to be fighting with, which is what I kind of feel like I’m doing a lot when I, it’s like I can sit here and tell you about how capitalism and consumerism is bad and then I…

This sounds like Spotify. You know what I mean? It’s like all of the people that I call my enemy and that I love to get self-righteous about and be like, “Oh, how could you have all these… How could you act this way?” All these victories, all I wanna have towards White supremacists and misogynists and people that are doing super harmful things, it’s like, when you get up to the line between people protesting and people counter-protesting, it’s like, I’m being just as angry and dense and stubborn, and maybe it’s because I believe that my side is nobler or better or righter, fine, but I’m still participating in a ruthless oppositional dynamic – and I have to recognize that. I have to recognize my own capacity for depravity and hatred and judgment that shows itself even as I’m criticizing other people for those very characteristics, if that makes sense.

That's really special. Philosophies aside, capital A / lowercase a ''art'' aside, what do you hope listeners take away from Little Oblivions and what have you taken away from creating it and now putting it out?

Julien Baker: Again, this is gonna sound very therapy jargon. But, I think that having compassion for yourself and practicing that makes you a more empathetic and more forgiving person. I really think it does. But it comes at the cost of the pain of looking into the ugliest parts of yourself. I think if you can look at the ugliest and the darkest and the worst things that you’ve ever done or said, or thought, and still care for your own happiness and for your own fulfillment, then it makes it so much easier for you to practice that with other people.

I don’t want to use a hashtag, a buzzword, phrase like “self-love is the answer” or whatever. Sometimes when things get oversimplified, I think they lose their salience because they become trite, and then people don’t take them seriously. And it took two years of me being turned off by the word self-compassion before I finally had compassion enough for myself to use it as a resource for compassion towards others. And if my music only does one thing, then I hope it makes people empowered to go through that process – empowered to look honestly at themselves; not judgmentally, but just honestly – and to use that as an exercise for empathy. That’s what I truly want.

I think if you can look at the ugliest and the darkest and the worst things that you’ve ever done or said, or thought, and still care for your own happiness and for your own fulfillment, then it makes it so much easier for you to practice that with other people.

It's funny, you talk about using self-love, or overusing or being afraid of it... It's interesting that you talk about it, because it didn't sound like you had a lot of self-love when you were making Little Oblivions. But it sounds like after the record came to be, you were able to take a lot of self-love out of it.

Julien Baker: Yeah, definitely. And I don’t know, you have to start with believing that you’re worthy of love in the first place. And so there’s a lot of that that was tied up in my having been socialized in a Christian faith tradition. Self-love seems antithetical to what you’re taught because everybody in church loves to cite scripture about making yourself less and thinking… In all things, think of others before yourself or not being prideful. Pride is a sin, right? And then the idea of loving yourself, and the idea of being arrogant or prideful or selfish, all those ideas get conflated, or at least for me, they became conflated. And it took a long time for me to understand how actually toxic that is to subscribe to a religious belief that suggests that you look upon yourself and your body and your thoughts with scorn for them being human and imperfect.

I was still very much in that mentality while writing this. I had lost the one thing that I thought lended me likability, which was all of my principles, my sobriety, my kindness. I was being a bad friend and a bad partner, and I was being a hurtful friend, and not a reliable friend, and not a reliable daughter, or co-worker or whatever. And so I didn’t believe really that I was worthy of anything. And it was such a repulsive concept for me, having lived like over 20 years of my life, learning that denying the self is a virtue. It was really challenging for me to see the virtue in caring for yourself, especially because I had been so turned off by people being like, “I’m going to… I don’t know, drink, like, start drinking vodka, like 10:00 AM and watch Netflix ’cause I’m sad. This is self-care.” And I was like, I don’t know if that’s… If just doing whatever you want is self-care. But yeah, again, it’s like one of those buzzwords, but it did… Yeah, I don’t know. How do you… I think I just reached a threshold of like, how much could you hate yourself before it’s so exhausting that you have to try an alternative, and the alternative is caring for yourself, and that has been serving me much better. [chuckle]

It took a long time for me to understand how actually toxic that is to subscribe to a religious belief that suggests that you look upon yourself and your body and your thoughts with scorn for them being human and imperfect.

I'm glad to hear it. If Little Oblivions can do 1% for someone else what it did for you, it'll have served its job well. Thank you so much for going on this journey with me.

Julien Baker: Yeah, I think so too, and of course!

As we end, who are you listening to right now, and who's been on your radar?

Julien Baker: Oh my gosh… First of all, that new Lake Street Dive record is crazy good. “Making Do” has been the only song I wanna listen to since it came out! I’ve been listening to Claud, which Phoebe told me about because Phoebe signed Claud to Saddest Factory and I was like, “Whoa, this is… I can’t believe I didn’t know about this before!” I’ve been listening to a lot of Torres ’cause she’s about to put out another record.

That’s always such a big question for me ’cause I’m like… Literally, last night I was doing a full listen through Kendrick Lamar’s discography, but then it’s like… That’s not an accurate representation of what I’ve been listening to. I was looking for a specific lyric that was stuck in my head and I couldn’t remember what song it was on, and then I was like, “Why don’t I listen through this artist entire discography while I’m cleaning the kitchen?” [laughter] So that’s the type of shit I do with my day.

We are complex creatures – we don't have only one thing going on at the same time.

Julien Baker: “We contain multitudes.”

Exactly. And a perfect way to end. Julien, it's a pleasure. I wish you and your loved ones all the best and health and happiness, and I hope speak to you again sometime very soon.

Julien Baker: I hope so too. Thank you for this conversation. Have a great day!

— —

:: stream/purchase Little Oblivions here ::

Stream: “Favor” – Julien Baker

— — — —

Connect to Julien Baker on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Alysse Gafkjen

:: Stream Julien Baker ::