Every other week, we chose a contemporary work of art or new media and engage it with an aesthetic of the past. In her first post of the series, Kate Butler looks at the 18th century iteration of Instagram, revealing that we’re not the only ones in history to idealize our moments while we’re still living them. Pictured above: Harbor at Sunset by Claude Lorrain.

It’s hot and crowded on the Piazza San Marco in Venice, but through the lens of your 3 by 5 inch iPhone screen, the sun and tourists are just players in your photographic imitation of grandeur. Your boyfriend – let’s call him Billy – wanders off toward the Grand Canal but you remain still amid the shuffle, poised to grab a slice of the visual feast. A bird catches flight. You snap the photo, put a filter on it, and think how pretty your lives are.

But before you can send it to Instagram your moment of beauty dissolves into cliché: between you and the Basilica, a herd of tourists hold up their smartphones. They snap at the birds, they snap at the buildings and with their faces planted to their screens, they silently populate the inter-web with a stream of filtered photos no more or less special than yours.

Which is to say that it’s hard these days not to associate the multitude of romanticized digital memories with our tech-centered culture of documentation. Yet it’s worth remembering that we’re not the first in history to divert our attention from the present moment to the encapsulated, digestible beauty of the Picturesque. That filtered and vignetted instagram photo, if remarkably contemporary, is an expression of an enduring desire to frame the visual world with the goal of making it pleasant to look at. It’s an expression of an enduring desire to capture experience, affecting as it is elusive, into a vision that’s worthy of our idealism.

Long before we applied filters to our moments there was the Claude Glass. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the pocket-size mirror rose to popularity its capacity to imitate the glow and gradation of a Baroque-era painting. Its darkened glass lowered the color key of a given land or street ‘scape, accentuating prominent features and playing down specifics while its rounded and convex form would create a vignette. In the time it takes today to snap a photo of a sun-lit canal, yesterday’s romantics could transport the “mellow tinge” of French painter Claude Lorraine’s sun-swept and utterly self-contained masterpieces to a city or pastureland of their own.

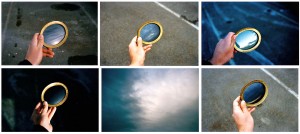

Above: the Claude Glass imitated the gradation and grandeur of Picturesque landscapes. The only catch? Tourists would have to turn away from a scene to look at it. Source: thesocietypages.org

That is, if they were willing to turn away from it. To see the glass’s Picturesque vision of the visual world tourists would have to look at a scene from behind, favoring the view through the dark little mirror to the real thing. For the draftsmen among them, the glass facilitated the creation of quick, idyllic sketches to show to friends and family upon return. The mode of recording was slower, even more contemplative, but the motive to record is all too familiar. With a Claude Glass in pocket, the tourist of yesteryear saw life with a visual appetite akin to the iPhone clad of 2014: that is, ready to embellish at the faintest glint of beauty and fine to turn away from it to do so.

There may be something exploitive about the pre-framed made-to-order vision of the Claude Glass or, in any case, the iPhone 5 or the iPhone 12 Refurbished, but the desire to capture idyllic versions of our lives is a romantic one at heart. Encapsulated in Claude Lorrain’s epic, classically precise harbor and pastoral scenes is a familiar longing for an all-encompassing beauty beyond the passing moment. Though his style so sought after by owners of his namesake glass may be out of vogue, our modern-day iteration – the tinted squares of Instagram – represents a similar idealism. In the way of Lorrain’s landscapes, they show us a world that glows with feeling, that’s more elegant than mundane, that expands into the distance, and where the stench and heat are subsumed by the pure golden and blue colors of perfect weather. By crop and by filter, our photos show us what we’ve seen and done with a nostalgia that the unphotographed life evades – a nostalgia for what may or may not have actually been.

It’s hot and crowded on the Piazza San Marco where the tourists continue to move across the square with an elegance that reminds you – if you could take out that commercial billboard at the far end – of an old master’s painting. With your phone now in your pocket, your hand is free to hold Billy’s as you stroll together toward the Basilica. Maybe a year from now you’ll remember this day by his photo of that bird, but as the moment stands you’re content to forget it as you walk beneath the chiseled archways into a room of gold-plated domes decorated with devotional figures of an era past. A squeeze of the hand, a look in the eyes. And then it comes to you: a rosy tint, a vignetted glow like a filter.