Petey USA reflects on the restless songwriting instincts behind ‘The Yips,’ a record that uses fiction, humor, and unease to grapple with anxiety, identity, and the fear of getting stuck. Moving between past selves, present-day clarity, and imagined futures, he opens up about resisting nostalgia, letting go of control, and why he’d rather save happiness for living than for lyrics – even as this album becomes his most emotionally precise work yet.

Stream: ‘The Yips’ – Petey USA

Petey USA doesn’t trust permanence.

He doesn’t revisit old records, doesn’t romanticize past versions of himself, and bristles at the idea that a finished album could ever accurately represent who he is now. To him, records are snapshots – useful, imperfect, and instantly outdated the moment they leave his hands. “The second you put something out,” he says, “it’s already a misrepresentation of who you are.”

That tension sits at the heart of The Yips, a record written quickly, under pressure, and without the luxury of overthinking. Produced alongside Chris Walla – the creative force behind Death Cab for Cutie – and released July 11th via Capitol Records, Petey USA’s fourth studio album builds a fictional world not to escape reality, but to tell the truth sideways – about anxiety, inadequacy, ambition, and the quiet fear that the systems we’re raised to believe in don’t actually work. It’s simultaneously his boldest and his rawest-sounding record to date, driven by a voice that often feels on the brink of fraying, strained not for effect, but because the songs demand it.

I’ve got the yips, read my lips

I used to run this town then I got sick

I can’t hear anything, I lost my sight

Can someone rub some mud over my eyes?

I followed all the rules, I showed up every day

Could you explain to me what’s making me this way?

I hope to God won’t pass it on, onto my kids

I wanna quit, I wanna quit,

I wanna quit, I’ve got the yips

– “The Yips,” Petey USA

The Yips arrives after a relentless stretch of touring behind 2023’s USA, Petey’s major-label debut – an album shaped by expectation, momentum, and the pressure of visibility. Still deep in an extended touring cycle, Petey found himself at a crossroads familiar to many working artists: The need to keep moving, colliding with the realization that overthinking had only ever made things worse. There wasn’t time to spiral, to micromanage meaning, or to assign weight where it didn’t belong. “I realized that none of that overthinking benefited me at all,” he admits. “So I’m just gonna write it and see what happens.”

The result is his most cohesive and emotionally grounded work to date – not because it chases clarity, but because it allows confidence and doubt, control and chaos, to exist side by side. You can hear that tension directly in his delivery – the way his voice cracks, presses forward, or sounds almost out of breath, as if catching up to thoughts moving faster than comfort allows. Throughout the record, Petey writes from multiple selves at once: Past versions still carrying shame, present-day clarity hard-won through distance, and imagined futures shaped by fear rather than fact.

That multiplicity isn’t a new invention. It’s the result of a creative life spent moving between distance and immediacy, abstraction and confession – and it begins well before Petey USA existed at all.

Before Petey USA became a solo project, Peter Martin spent years in the critically acclaimed indie band Young Jesus, where atmosphere often carried as much weight as narrative, and meaning lived in suggestion rather than statement. Debuting in 2021 – first as Petey, and later Petey USA, Martin’s solo project emerged as a sharper, more immediate outlet – one rooted in inner monologue, humor, and emotional candor, delivered with the precision of someone who had already learned how easily distance can become a shield.

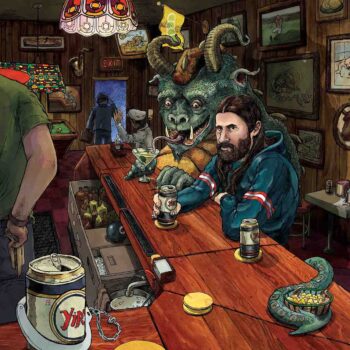

If Young Jesus explored feeling from afar, Petey USA steps directly into it – and nowhere is that more evident than on his latest LP. Set inside a fictional dive bar populated by anxious regulars, wounded optimists, and men trying to make it through another night without imploding, The Yips unfolds like a series of overlapping confessions. On the title track, Petey opens the door with a blunt admission – “I’ve got the yips, read my lips / I used to run this town, then I got sick” – establishing both the album’s tone and its stakes. Charged, churning, and utterly all-consuming, his voice sounds both confrontational and exhausted, as if naming the problem is the only way to keep it from swallowing him whole.

Built around a restless, forward-driving pulse, “The Yips” feels intentionally overwhelming – a walking-tempo spiral where every idea sticks because it isn’t given time to be sanded down. As Petey later puts it, it’s one of the rare songs where “everything we threw at it just stuck,” a sentiment that mirrors the song’s refusal to resolve neatly or politely. The song’s relentlessness mirrors its subject: A mind that won’t slow down long enough to decide whether it’s panicking, confessing, or asking for help.

From there, “Model Train Town” spirals through guilt and calm in equal measure, its uneasy stillness punctuated by the now-iconic line, “I felt relaxed and I felt guilty,” a contradiction that echoes throughout the record. One of the album’s most emotionally layered moments (and an undeniable highlight), the song captures the strange discomfort of feeling peace under the wrong conditions – a tension Petey traces back to wanting to share something deeply personal and realizing that experience will never fully translate. The track moves patiently, almost gently, before collapsing inward, its emotional release followed by sudden quiet, as if the song itself needs a moment to catch its breath.

“‘Model Train Town’ started with this sad, vulnerable, almost embarrassing feeling of being really excited about something and wanting to share it with someone you love – wanting them to experience it through your lens – and realizing they’re just seeing it differently,” Petey explains. “You don’t get to share that experience together, and you start to realize that experience is just through the eyes of the beholder.”

“Then it goes further – thinking about how relationships are affected by millions of outside forces, all these things that touch something you want to keep pure. It’s kind of a selfish thought, like, ‘I want you to fit into my world and see things the way I see them,’ and then realizing that’s impossible. So I imagined this apocalyptic scenario where everything is destroyed and it’s just you and this person you love, finally getting a clean slate – and feeling calm for the first time. And then feeling really guilty, because the conditions that allow you to feel calm are impossible, and theoretically really destructive to everything else.”

I had a f*ed up dream

The whole world had ended violently

The only people left were you and me

I felt relaxed and I felt guilty

Then I realized that you are all I need

Let’s buy a mobile home and sell all of our things

I’m still overwhelmed but this feels like a start

I laid my head upon your beating heart

It’s one of the rare moments on the record where calm arrives fully formed – and immediately feels suspect, less like relief than a temporary truce. The peace the song imagines is fragile, conditional, and quietly unsettling, shadowed by the knowledge that it only exists because everything else has fallen away. In that tension – between comfort and conscience – “Model Train Town” captures one of The Yips’ central anxieties: The fear that feeling okay might itself be a kind of moral compromise.

Where “Model Train Town” wrestles with the guilt of feeling okay, “The Milkman” drops further down the ladder – into a space where the absence of feeling becomes its own kind of crisis. “The Milkman” sits at the emotional low point of The Yips, staring directly at numbness without flinching or flourish. Anchored by the devastating admission, “This is what it feels like to not feel anything,” the song refuses catharsis, instead leaning into emotional suspension. Petey’s delivery is notably restrained here – flat, drained, almost affectless – a choice that feels deliberate rather than detached, as if any added inflection would be dishonest. The arrangement mirrors that emptiness, leaving space where release might normally live, and forcing the listener to sit with the discomfort of feeling nothing at all. It’s not despair dressed up as drama; it’s the quieter, more unsettling realization that the absence of feeling can be just as frightening as overload.

If “The Milkman” captures emotional absence, songs like “Breathing the Same Air” reach tentatively toward connection as a means of survival. Built around the quiet understanding that closeness doesn’t always arrive with clarity or resolution, the track clings to the idea that sometimes simply sharing space has to be enough. There’s a gentleness to it – musically and emotionally – that feels earned, not sentimental, as if Petey himself knows how easily that intimacy – and in turn, that tender camaraderie – could slip away.

This fragility deepens on “As Two People Drift Apart,” a song defined as much by what it withholds as what it reveals. Its restraint amplifies the sense of distance – and weight – it describes, capturing the slow, almost imperceptible process of watching a relationship change in real time. Rather than dramatizing separation, Petey lets it unfold quietly, mirroring the way disconnection often arrives – not with a rupture, but with a gradual loosening you only recognize once it’s already happened.

Across the rest of The Yips, Petey continues to sketch variations on the same unease – songs that don’t resolve so much as hover. Tracks like “Spirit Animal,” “This Bucket of Water,” and “God Is In The Gray” feel less like statements than emotional weather patterns, drifting through the album’s dive-bar world without demanding interpretation. They reinforce the sense that this record isn’t chasing answers, but documenting states of being – moments where clarity never quite arrives, but honesty still does.

When Petey talks about all these songs, he’s quick to reject the idea that they function as direct autobiography. Instead, he frames The Yips as a form of fiction shaped by truth across time. “It’s a combination of how I felt in the past, how I feel now, and how I imagine I could feel later,” he explains. “So it feels autobiographical, but I’m also fibbing a lot.” That push and pull – between honesty and invention, clarity and fear – gives the record its emotional elasticity. Writing from what he calls “three different planes of existence” allows Petey to explore anxiety without being consumed by it, to imagine worst-case futures without mistaking them for prophecy. “Life is really good right now,” he says plainly. “I’m not super interested in writing an album about that.” Instead, he returns to discomfort as a creative engine – not to wallow, but to understand it, and maybe, in the process, make it feel a little less lonely for someone else sitting at the bar.

As we sat in the corner

Had the bar hand throw the game on

No one asked a single question

That meant anything to anyone

Know that my only intention

Is to be there when you call me

Sometimes breathing the same air

Has gotta be enough

Each song on The Yips feels like a different stool at the same bar – different stories, same unease.

While the people and the bar are imagined, the world Petey built is familiar – a slice of home. Raised in Midwestern suburbia, Petey has spent much of his adult life interrogating the promises baked into that upbringing: The idea that success, stability, and fulfillment arrive if you just follow the prescribed path. “You hit your late twenties or thirties,” he says, “and suddenly you realize the thing you were chasing isn’t actually what you want.” The Yips isn’t just about that realization – it’s about what happens when it starts to seep into your bones, when confidence falters, focus slips, and you’re forced to confront the possibility that the system itself might be broken.

Waited by the well while the well ran dry

Took a bucket to the lake for a fresh supply

Now I’m lost at sea while the sirens sing

This is what it feels like to not feel anything

Yeah, here’s to being authentic!

Three cheers for being yourself!

What if the most accurate version

of me is acting like somebody else?

Are you attached to the action?

Are you attached to me?

A diagnosable condition, every decision I make

Dying by the well while the well ran dry

Made a promise to myself, stick a needle in my eye

Gotta get my life together before this spring

This is what it feels like to not feel anything

– “The Milkman,” Petey USA

In our conversation, Petey opens up about letting go of control, resisting nostalgia, and why he’d rather save the happiest parts of his life for living than for lyrics – even as The Yips becomes his most expansive and emotionally precise work yet.

He talks candidly about fear – not of failure, but of “losing his shit,” of one day losing his footing entirely – and about writing from three different planes at once: Past versions of himself, present-day clarity, and imagined futures he hopes never arrive. Fiction, for Petey, isn’t a mask. It’s a way of telling the truth without flinching.

What emerges is a portrait of an artist learning how to make peace with uncertainty without letting it swallow him – and a record that turns private spirals into something communal, cathartic, and unexpectedly tender.

It’s an album for anyone who’s ever felt both relieved and guilty to finally slow down, for anyone who’s ever thought, “I want to quit,” but kept going anyway – not because the answers are clear, but because staying present feels like the only honest option left.

— —

:: stream/purchase The Yips here ::

:: connect with Petey USA here ::

— —

A CONVERSATION PETEY USA

Petey, I caught your show with Medium Build at Levon Helm this summer, and I just want to express how special and cool that night was. What was that tour like for you guys?

Petey USA: It was awesome. It was really, really special for me because I have a lot of performance anxiety, and Nick doesn’t. Having someone to share the stage with who’s so confident, dialed, and such a good musician took so much pressure off me. I felt like half the pressure was gone, and it was really good. It felt very freeing and super fun, and unplugged. I didn’t have any chords – that stuff always really trips me out – so it was awesome. And I love the Northeast. I loved everywhere we went. It made me want to… yeah. I’m jealous.

Yeah, it was a cool space. Levon Helm is such hallowed ground, too. It's such a special place to play, to make music, and the acoustics are off the charts there. Hearing your music in an acoustic setting is great in its own right, and then that space amplified everything – literally and emotionally.

Petey USA: Yeah, it’s wild. I’m trying to become a cover band. I don’t write the songs that way at all, so I often… it’s funny – I make all my songs on the computer, and then I have to learn how to play them on guitar, and that’s really hard for me. So it’s kind of a big growing experience, but that was fun. It was really fun.

It brought me back to what I think music was always meant to be, which is a communal, community experience. So, your new album The Yips has been clearly a long time coming – it's actually been two years and change since your last record, USA came out. What is your relationship with that record like these days?

Petey USA: Honestly, unless I’m literally playing the songs live, it’s kind of out of sight, out of mind. When I’m done with something, I’m done with it. I don’t really have the brain space to keep thinking about it, and that’s how I think about work in general. I’m really trying not to hold on to things once they’re out there.

So unless I’m performing the song live, I’m not thinking about it at all, and I often forget it exists. Which is cool, because a lot of times when I’m playing stuff live, I’ll be like, “Oh, damn, this is really cool. This is fun.” I haven’t listened to those recordings in probably two years, and that’s a reflection of how I think about making music. I’m constantly changing my mind about things and thinking differently, and an album is such a snapshot of where you’re at in a moment. It can feel weird to revisit.

I’m really, really sensitive to being misrepresented, which is funny, because when you put an album out, that’s basically a permanent misrepresentation of who you are now – because we change so much over the years. I think that’s why I don’t really look back on it. And when we’re playing the songs live, I can kind of feel like I’m in a cover band.

You know, I like that approach, though, because I think about... There are, I mean, a ton of bands that I'm actually going to be seeing this year who do, for better or worse, live in their past. Is this? They're going on this massive tour right now, garnering... Everyone's talking about it. My Chemical Romance has brought back The Black Parade, revised it for 2025. So there's... It's a little bit different than it used to be. But, like, there's a bunch of bands like that who are experiencing this renaissance from 2025, 30 years ago.

Petey USA: Yeah, the Legacy Tour stuff.

Yeah, and listen, I get it. There's money in it. But, like, it forces you to dwell in former versions of yourself in songs that, like were made in the past. And I wonder, maybe we all get there eventually. Maybe we're all ultimately just playing the greatest hits. But that's not where we are today.

Petey USA: Right. Right. I saw The Cure at the Hollywood Bowl when they came back. I don’t know if you saw the most recent Cure tour, but it was really inspiring. They played four or five new songs that just sounded like Cure songs. You had the fake-sounding keyboard piano, the minute-and-a-half-long intros, everything. It was like, damn, these are new Cure songs, and it’s awesome. And he’s 70. I don’t know, I really liked that. I’ve gone to a bunch of legacy emo 20-year reunion concerts, because that’s how I grew up, and I’ve been kind of sad at the end of some of them.

As I said earlier, The Yips feels special. It’s emotional. It’s evocative. It’s layered. I want to dive into it, but I want to start at the top. Following USA, what was the transition like into writing these new songs? At what point did the concept come about? Was it something that came together after the fact – realizing these songs shared a theme – or were you conscious of it in the moment?

Petey USA: Yeah, I think it’s the latter. I wasn’t conscious of the moment. With USA, there was a lot of pressure attached to it because it was my first album with a major label, and my first album outside of the COVID surreal bubble. There was a lot of overthinking and overprescribing, and attaching a lot of meaning to things that were really just constructed by my anxiety and all that stuff.

I put it out and realized none of that overthinking benefited me at all. None of it mattered. All the mulling over – maybe it did, maybe I’ll find that out way later – but it didn’t feel worth it at the time. This time, I was on the road. The USA touring cycle got extended a lot because I got a lot of support offers, so I was still touring a year-plus after it came out.

When it came time to write another record, the pieces were kind of put in place for me by my team while I was on the road, which gave me hard deadlines. I was like, okay, I literally can’t overthink this. I can’t take my time with it. I’ve got to do this, and it has to be done. I wanted to keep up with the cyclicality of everything. I’m not rich, so I’ve got to play the game. I couldn’t overthink it at all. I didn’t have the time. I was just going to write it and see what happened. And as it turns out, I got to work with my favorite musician basically ever, which is crazy. The concept and everything came later, when I realized all these songs were living in the same world – which makes sense, because I wrote them very quickly.

Chris Walla has been one of my favorite creatives over the years, and I'm so curious to hear how his fingerprints are scattered in these songs and what that experience was like working with him and bringing these tunes to life.

Petey USA: I think that, first of all, it was just surreal because I’ve been the biggest Death Cab fan ever since I was in sixth grade. I was really aware of how he kind of taught me how to play guitar. I’ve always been hyper-aware of his voicings, especially the way he navigates chord progressions and all that stuff. But I didn’t really have visual proof of his contributions to the Death Cab records. I’d always theorized about it and watched YouTube videos and all that.

Yeah, but Ben is such this dominating force. You're like, when does Ben end and the rest of the band begin?

Petey USA: Yeah. Seeing Chris play guitar in a room and seeing what he added to this record really brought his contributions to my favorite records of all time into focus – The Photo Album, We Have the Facts, all that stuff. It was really cool to actually see it. It was pretty surreal. There were moments where I forgot who he was and who I was working with, because we had so much to do and I couldn’t get bogged down in the fandom of it all. But there were certain moments where he’d play something and it would just snap into focus for me. I’d get pretty emotional about it, and then try to calm down because I didn’t want to be embarrassing or weird.

Do you have any highlights from his contributions, or specific songs he touched that you're especially happy to have out in the world?

Petey USA: Yeah, when I’d give him the guitar to do feedback takes – he can play guitar feedback like it’s its own instrument, like a synth or something – the control he has over that was pretty mind-blowing to me. He’s just a masterful guitar player.

I’m not a great guitar player. I play guitar in my own way. I tune it in weird tunings. I play all downstrokes. I’m primarily a drummer, so I play guitar like a drummer – very percussive and sloppy. Having him bring a much more human, full element to the guitar playing – the variations on the chord voicings and all that – was pretty mind-bending.

It was really nice to be able to hand over the guitar when I hit a wall and have him bring it to life in ways I never could have imagined. It’s all over the record. There isn’t really a specific spot – it’s everywhere.

You mentioned earlier that you bring songs to life first on the computer. Was this a situation where you brought him 10 or 15 demos you’d already fleshed out, and then worked on bringing them fully to life together in the studio? Or were they more half-finished songs that you developed collaboratively from there?

Petey USA: Yeah, I brought him demos that were half-finished song demos. Then I brought them into the studio, and that was that. It was super collaborative. I had all the lyrics done and the vocal parts, but in terms of arrangement and everything, this was definitely the most collaborative thing.

There are a lot of common threads running through this album. Out of curiosity, what were the first couple of songs that got made for it – the blueprints that helped pave the way?

Petey USA: The first demos I sent over included a demo for “Ask Someone Else” that sounded way different – it kind of sounded like a Tom Petty song. The first demos I sent over got completely transformed. They had different song names and different arrangements.

That’s the only one I can really point to. It kept the same name and the same chord progression, but it was totally halftime. Then, kind of at the eleventh hour, I rearranged it and turned it into a pop punk song.

How do you feel that song – and those early sessions – helped set the tone for the album?

Petey USA: It was kind of weird. Chris originally wanted to do the record because he saw the Audiotree performance of the live band. Because he was flying from Norway to do it, he saw something that worked and thought, okay, let’s do that. So I wrote the songs with live-band arrangements in mind, and I realized that isn’t really my strong suit.

It really just took us hanging out in person for us to get there together, so I didn’t have to do that over the phone or anything. It evolved into getting a blueprint down in a live-band setting, and then going in and doing surgery together. As it went on, I started writing songs the old way. Once things were moving and we knew we were making good stuff, I gave myself permission to try things that way again.

That meant writing on synth and then coming in and building the instruments around it. He says it a lot – it really was a patchwork quilt. We did 80 different methods, and they all stuck in one way or another. That’s what we’re left with. I don’t know. It’s pretty cool.

I have to take a moment to say how excited I am to talk with you, not only because I love this album, but also because “Model Train Town” has been one of my favorite songs that I've heard all year long. It still hits as fresh and hard today as it did when I first heard it –there's so much raw emotion pent up in the song. Those lines, “I felt relaxed and I felt guilty.” There's so much to say about them, and I'd love to learn more about where that track came from and what it means to you.

Petey USA: Yeah, “Model Train Town” is about a couple different things. Obviously, like you said, there are a lot of layers. I started with the feeling – that sad, vulnerable, almost embarrassing feeling of being really stoked about something, sharing it with someone you love, wanting them to experience it the way you do, and getting a muted reaction back.

It’s that letdown of realizing they’re seeing something differently, that you don’t get to share the experience together. And then realizing that experience in general is kind of through the eyes of the beholder. From there, it goes a bit further into thinking about how relationships are affected by all these outside forces – millions and millions and millions and millions of micro outside forces – that can affect something you want to feel so pure and untouched.

That’s kind of a narcissistic or really selfish thought – wanting someone to fit into your world and see things the way you see them – and realizing that’s impossible. That’s just not how life works. So then imagining this apocalyptic scenario where the entire planet is destroyed and it’s just you and the person you love. You finally get to have this clean slate together, unaffected by all these extraneous forces.

That’s when you feel calm for the first time, and then you feel really guilty and then bad – because the conditions that allow you to feel calm are impossible and, theoretically, really destructive to everything else. So yeah, that’s what the song is about. I really like that one too.

There’s so much fun in the way the song builds to that emotional release – the shifting perspectives, the self-awareness of having your own glass shattered, then realizing you can’t see this other person through someone else’s eyes. That dual lens is really compelling. What I keep coming back to across The Yips is the emotional release and the lyrics. In “The Milkman,” you sing, this is what it feels like to not feel anything. In “Breathing the Same Air,” sometimes breathing the same air has gotta be enough. There’s a real yearning for human connection running through the record. I’m curious what that process looks like for you. When you’re writing a Petey USA song, what’s happening when you’re pouring those words out?

Petey USA: So this whole album is, again, it’s like, it’s interesting. I mean, like many fiction books, it’s like, it’s a combination of how I felt in the past, but no longer feel. How I currently feel and how I’m imagining I could feel later based on how I felt in the past. And so in that sense, the looking ahead is all sort of like fiction writing, but then there’s like truth mixed in with how I feel now. And then there’s truth mixed in with how I felt in the past. So it’s, it feels like autobiographical, but I’m also like fibbing a lot. I don’t know. And that’s kind of what it is. It’s like using my own feelings to imagine a realistic world that’s not necessarily accurate, but it totally could be. And that’s the only way I know how to do it. ‘Cause I mean, like right now life is great. Like life is like… things are really good. I recently got married to a person that like I’m obsessed with.

Congratulations!

Petey USA: Thank you. Things are f*ing awesome. And I’m not super interested in writing an album about that. I think Chance the Rapper tried and kind of got flamed for it. I want to reserve the good parts of my life for just living them, not working.

A lot of it comes from sitting down and imagining – or dwelling on – times in my life where things weren’t so great, specific parts of my life that aren’t great now and that I need to work on, and then imagining my life turning into absolute shit later, informed by past behavior. That’s kind of how I wrote this album. That’s how I write a lot of stuff, which is great, because that’s three different planes of existence to draw inspiration from.

I feel like I'm speaking to a kindred spirit. For me, writing is where I excise those harder thoughts and feelings that consume me when no one's looking.

Petey USA: Yeah. It’s so funny with songwriting. It’s kind of annoying. With “I Am Not a Cowboy,” everyone’s like, oh my God, did you get a divorce? And it’s like, no. Songwriting is so perceived to be autobiographical. And if you’re not doing that, then you’re doing a concept album or something. I don’t know.

No one reacts that way to other mediums. If someone writes a really fed-up horror movie, no one’s like, are you okay? But with music, people listen to it and start assigning it to your personality. I don’t think people consume other f*ed-up mediums while explicitly thinking about who wrote them and why they wrote them.

That’s a great analogy. Over the past 10 years at Atwood, I’ve tried to unpack this too, because I’ve noticed the same thing – this perception, especially over the last 50 years or so. It feels like the Dylans of the world helped cement the idea that if you write and sing your own songs, you’re telling your own story. Before that, there was Tin Pan Alley – writers like Carole King creating incredible songs for artists from all walks of life. Somewhere along the way, if you didn’t write your own songs, you were seen as a fraud, like you were only doing half the job. And listen, I love when artists sing what they make. You go down to Nashville and that world is still very much alive. But it’s funny how musicians are expected to have no illusion – if you’re singing it, it must be true.

Petey USA: Right. Yeah. Unless you’re Coheed and Cambria or something, which I think is the coolest thing ever. But I’m certainly not capable of that. I’m also not capable of doing something strictly autobiographical. So like I said, I think the three planes of existence that I lay out guarantee that I’ll always have stuff to write about. Because again, I’m always changing my mind about stuff. Every year I just think differently about things. Every year I feel differently about my past, you know what I mean? And so it bodes well for making a lot more albums for years to come.

I love that creative approach. If you'll indulge me, I'd love to kind of just talk one second about the album title itself, The Yips. “The Yips” itself really does set the tone in so many different ways. I love the way that you open it with “I've got the yips, read my lips. I used to run this town. Then I got sick.” There's a lot there, but I’d love to understand, even just from this little snapshot of a former moment that you wrote in, what does this album title mean for you – and what inspired you to name the album ‘The Yips’?

Petey USA: I touch a lot on Midwestern suburbia themes, and I’m really fascinated by it. I grew up in it, I’m really affected by it, and it defines my whole life. I’m so conditioned by Midwestern suburbia in a big, big way.

It’s something I think about a lot, something I get sad about a lot, and something I’m reminded of constantly. There’s this image of a really confident, athletic high school man who grows up pursuing an ideal that was conditioned into him by his father, who was also chasing that same ideal – and was also depressed. It’s this coming-of-age realization where you’re 30 years old and the thing you’ve been chasing isn’t what you actually want.

A lot of it is really f*ing stupid and silly – constructed by ’90s consumerism, capitalism, sexism, misogyny, racism, all this bad shit. And it all starts catching up to you like a poison when you’re in your late 20s or early 30s. Infused in that is alcoholism, opiate abuse, over-prescription of drugs, Adderall – all this really dark shit that comes along with the hidden, dark demon shit of growing up in suburbia.

The paradox is that this is supposed to be the ideal. This is what we’re all supposed to be striving for. All of our dads strived for it. And we didn’t see them fail, but we saw proof that it didn’t work in terms of salvation or personal happiness. And yet here we are, still pursuing it, even though the proof is right in front of us. I’m obsessed with that idea because it’s so sad. It’s so f*ing sad, and it’s so pointless.

I have tons of reminders of that in real life, and I think a lot of people do. That’s why I love writing about it. The whole idea with The Yips is that it just stops working – the system stops working, you stop working within the system, you get in your own way, you start tripping up, and you lose your mind at the revelation that none of this is it. That’s kind of it. It’s not totally it, but that’s kind of it.

Another thing about me is that I’ve gone through periods of deep depression. I’ve gone through periods of substantial substance abuse. I’m not an addict, but there are times I look back and think, oh wow, I was really getting after it. That said, none of that feels unusual or uncharacteristic of people with my upbringing. I’ve always felt like my mental faculties were pretty consistently in check.

But my biggest fear is that one day I’ll lose my shit – just absolutely lose my mind. I have no evidence that’s going to happen, other than bouts of depression. And bouts of depression can really, really derail your life. So even though my life is amazing right now, I have this consistent fear that one day I’ll go crazy. To me, that’s The Yips. It’s losing your step. Again, there’s no evidence to support that it would ever happen – it’s just something I constantly think about.

I can relate to that in a weird way. I’m also a product of American suburbia. I grew up with the idea that I’d go off, have a coming-of-age experience in school, then come back, settle into suburbia, and start my own family. I can think back to my own personal yips moments – those times when the glass shattered and I realized, no, I don’t want this. Did you have moments like that that crystallized your own path away from it? Or do you feel like we’re all kind of stuck in this toxic cycle of thinking that this is what we need?

Petey USA: The thing is, I never actually wanted it. In that whole diatribe I just went on, I use we as the community I’ve observed. I had enough experience to know it wasn’t what I wanted. But because I was raised in it, I didn’t feel equipped with the knowledge or confidence to exist successfully outside of it. When I graduated and moved to LA, I really ate shit for eight years. I couldn’t figure it out. I couldn’t interview for jobs. I felt like I had no skills. I didn’t feel employable. I didn’t feel worthwhile in any sense. I didn’t have the skills necessary to exist outside of the suburban male construct.

If I had committed to that at 18 – said, this is my plan, I’m going to major in this, learn this, and get X job from so-and-so’s dad after I graduate – there would’ve been a path. But I resented that and pushed it off. And because of my conditioning, I didn’t try to do anything else. I was just like, I’m not going to do that. But I also had no plan to get my shit together in any other way.

So I was left skill-less and clueless. I had a dead-end job I absolutely couldn’t get out of. And I also have f*ing horrible ADHD. I’m undiagnosed, but whatever’s going on is something someone wanted to put me on Adderall for when I was six, and my mom wasn’t having it – God bless her.

Then COVID hit. The world shut down, and the constructs sort of ceased to exist, at least in my mind. I was like, holy shit, this is my time. Before COVID, I was clean-cut. I worked in the mailroom of a corporate office, so I had to look nice. COVID hit, I grew my hair out long, grew an insane beard. I was rail thin. I was eating ingredients because I didn’t know how to cook – just handfuls of ingredients. I lived in a tent in my friend’s backyard because I couldn’t pay rent. And I was the happiest I’d ever been in my entire f*ing life.

I was deep in my Buddhism bag – reading the Tao every day, little short excerpts about not holding on to work. That’s why I don’t listen to my old records. I was so happy. Then I wrote Lean Into Life, and then I had a career. That was my path into doing this shit. But it took an absolutely world-shattering event to get me out of the f*ing horseshit loop I’d put myself in. So…

This is a tangent, but have you listened to The Killers’ Pressure Machine? It touches on a lot of the same themes we’ve been talking about – small-town Americana, forgotten people, those inherited loops – which I think connects to where Brandon Flowers grew up. There’s something interesting about so many American songwriters looking back at these cycles and questioning whether they’ve actually led to positive outcomes for generations.

Petey USA: Yeah, the whole COVID thing you’re talking about – that’s it in summation. I felt relaxed and I felt guilty. That’s the “Model Train Town” vibe.

Beautifully said. Do you have any personal favorite songs off The Yips that you're really excited for people to discover? Any highlights that resonate with you that you're looking forward to playing live?

Petey USA: Yeah, we played the three album release shows and played the whole record all the way through. That was really cool. It felt ambitious and really scary, but everyone really showed up. We learned it super fast, got it sounding good, and I’m so happy that, for the first time, we can play all the songs on the record.

I don’t do anything unless someone forces me to do it, so I’m really grateful for that. I really like “The Yips.” It’s so fun to play. It has a really nice walking tempo. That song is one of the rare ones where, as Chris said, everything we threw at it just stuck. Everything on the record is kind of like that – we tried it all, and it’s all on there.

Yeah, like the trumpet blast. There's a lot of little sounds here and there.

Petey USA: Yeah, yeah, it’s really cool. It’s not something I would’ve thought a couple years ago that I was capable of making. When I listen to it, I’m like, this sounds like a classic record. And I’m really proud of it. It’s also super fun to play live, so we’ve been playing that one a lot.

I really like the song “I’ll Believe You.” That one really sticks with me. I keep going back to it. Lyrically, I really like it. And percussively, I really like it too. As a drummer, I gravitate toward the ones that are more percussively driven. And then “Model Train Town,” just because, lyrically, it’s my favorite. Yeah, those three stick out the most for me.

Do you have any lyrics that really resonate that you're particularly proud of?

Petey USA: I wrote it in 15 minutes. I remember exactly where I was – I was on the beach in Chicago. And when I put the pen down, I was like, “This is good.” I rarely feel that way. So I think holding on to that feeling is why I always come back to it.

I was like, “This is good.” There’s very little confusion for me about thinking that it’s a good song. I really like it. It feels very true to me. I didn’t have to bend any pipes together to make it work – it just sort of flowed out. It’s simple. It’s short. And it’s something I wanted to accomplish, and I feel like I accomplished it. So yeah, I’d say that one.

What do you hope listeners take away from The Yips, and what have you taken away from creating it and now having it out in the world?

Petey USA: I think I wrote it to be consumed like a movie – to imagine yourself in this world, and hopefully find catharsis, knowing that I feel some of the shitty thoughts you feel. I imagine some of the shitty things you imagine. I worry about some of the things you worry about. I think that if you can relate to some of the really hidden, deep, dark secrets in the lyrics, and feel less alone, that would be really cool. That’s what I’m hoping for.

“Here's to being authentic. Three cheers for being yourself. What if the most accurate version of me is acting like somebody else?”

Petey USA: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

That's really cool. Who are you in the spirit of paying it forward? Who are you listening to these days that you'd recommend to our readers?

Petey USA: Who am I listening to these days? Ugh, I’m so bad at this, because I missed so much old music when I was younger. I’m just getting into the classics now, and I’m like, holy shit. It’s funny – my friends make fun of me. I’ll be like, oh my god, dude, Pink Floyd is blowing my mind. And they’re like, yeah, dude, I listened to that in high school.

I’ve been cleaning my house and listening to metal, listening to Yes. Listening to… what else am I putting on? Bob Seger – just kind of corny road-trip music. Listening to Dire Straits. It’s awesome. Just all the shit I missed. I do need to plug a new artist, so let me think for like 30 seconds. It’s funny – the way I listen to music is so passive. It’s always someone else showing me something in the car. It’s always me freaking out, like, this is f*ing amazing, and then immediately forgetting to listen to it on my own.

I have a laundry list of bands that I want to one day get into and have yet to do that.

Petey USA: Yeah, I think Cameron Winter is an absolute legend. I think the internet goes both ways these days – there’s no middle ground. It’s either this thing is f*ing horrible and people are being unreasonably mean, or this guy is a genius and people are being unreasonably nice. And it’s like, can we just hold off on the genius thing? Relax.

But I will say this Cameron Winter album absolutely deserves all the accolades it’s getting. He seems like a f*ing old man stuck in a young person’s body. I think he’s only 23, which is f*ing mind-blowing. It’s really insane.

He’s one of the few new artists getting this much positive praise where I’m like, oh damn, this is actually even better than everyone’s saying. That’s pretty mind-blowing. I can’t wait to see what he does in the future. And how cool is it that someone this young and this talented is doing this shit? That’s how I feel about it. It’s inspiring. It’s exciting.

Now that you got to work with Chris Walla, is there anybody else on the metaphorical bucket list that you want to dream of working with next?

Petey USA: No, no, I’ve got none. I did it. But it’s funny because before I worked with Chris, I would have said the same answer, because I just don’t think that way. I’m literally never thinking of it. And I often have to be reminded that certain people are my favorite, if that makes sense.

Like, every time someone’s hand me the aux cord and says play something, I forget every song ever written. I mean, I rarely choose to listen to music. That’s why I love having CDs in my car. I just like having things there for me. But if you give me Spotify, Apple Music, and say pick a song, I will literally just draw a blank. I’ll forget what music is and what to do. I just can’t. There’s just too much.

Cool. Is there any chance in the near or far future that we get a studio version of “Two Dudes,” the song you and Medium Build played on tour?

Petey USA: Oh, yeah. Yes, there is. It exists. I don’t know when we’re putting it out. They filmed a documentary for that tour, so we’re probably holding off for a cross-promotional thing with whatever they came up with.

That's very exciting. Cool. Well thank you so much for your time, and congratulations on this record. It's been so much fun to speak today, and I really appreciate diving in deep with you.

Petey USA: Thanks so much.

— —

:: stream/purchase The Yips here ::

:: connect with Petey USA here ::

— —

— — — —

Connect to Petey USA on

Facebook, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© courtesy of the artist

The Yips

an album by Petey USA

© courtesy of the artist

© courtesy of the artist