~Singer/songwriter Noah Kahan reckons with the cost of growing apart on “The Great Divide,” a fiery, feverish re-entry that unpacks the quiet fractures that form over time – between old friends, past selves, and the lives we thought would keep running parallel. In tracing what’s left unsaid and what can’t quite be repaired, the song sets the emotional thesis for Kahan’s upcoming fourth album ‘The Great Divide’ – a record that finds him looking back honestly at who he’s become, who he left behind, and everything he’s finally ready to say out loud.

Stream: “The Great Divide” – Noah Kahan

Distance doesn’t always announce itself loudly. Sometimes it forms quietly – between who you were and who you’ve become, between the people who knew you before everything changed and the person standing here now, trying to explain it.

“The Great Divide” is a song about those unspoken distances: The friendships that drift without ceremony, the versions of ourselves we can no longer reach, the words we never found the courage to say when it mattered most. It’s about the ache of realizing that two people can grow up side by side and still end up worlds apart – and the emotional reckoning that comes with standing on opposite ends of that widening space.

Released January 30th via Mercury Records, “The Great Divide” is the title track and first offering from The Great Divide, the forthcoming fourth studio album from Noah Kahan (due out April 24). A fiery, feverish eruption of electric guitars and unguarded feeling, the song wastes no time easing listeners back into Kahan’s world. Instead, it plunges straight into the deep end – churning with restless momentum, bristling with urgency, and carried by a vocal performance that feels less sung than exhaled. For all its brooding introspection and emotional weight, “The Great Divide” is an upper: Cathartic, all-consuming, and strangely invigorating in the way it turns ache into motion.

That emotional immediacy has long been at the core of Kahan’s songwriting. Since emerging as a major label–signed singer/songwriter in the late 2010s, the Vermont native has built a career on radical honesty – tracing anxiety, self-doubt, belonging, and growth across a steadily evolving body of work. His 2019 debut Busyhead introduced a writer unafraid to sit with discomfort, while 2021’s I Was / I Am captured a moment of reckoning and self-examination – an album rooted in acceptance, reflection, and the uneasy recognition that growth often begins before we know how to carry it. As Kahan explained at the time, “The album is about taking stock of the person you were and how that’s made you the person you are… I try to document my life through songs and explain the obscurities of my thoughts and experience in a way that’s relatable and current to me.” It was a record about recognizing change, even as he was still learning how to live inside it.

Then came 2022’s Stick Season – the career-defining breakthrough that reframed not just Kahan’s sound, but his relationship to success, home, and himself. Turning away from pop formalism and toward folk storytelling, the album rooted itself deeply in place – in Vermont and New England, in small towns and long winters, in the push-pull between pride and resentment that comes with knowing exactly where you’re from. These were songs about staying and leaving, about loving home while feeling trapped by it, about reckoning with memory, mental health, and the quiet weight of inherited identity. Stick Season wasn’t a reinvention so much as a realignment: A choice to write toward truth instead of expectation. “I realized that I wasn’t finding happiness or creative fulfillment in trying to be a star and trying to be relevant,” Kahan told Atwood Magazine in conversation. “What made me happy was writing these songs and making this music… telling stories and speaking about this place I love and have such an interesting relationship with, which is Vermont.”

That decision changed everything. What began as a deeply personal, regionally specific folk record resonated on a massive scale, transforming Kahan from a rising singer/songwriter into a household name

and ushering in an extraordinary three-year run of global acclaim, sold-out arenas, and cultural ubiquity – without ever abandoning the intimacy, vulnerability, or emotional specificity that brought listeners in to begin with. Songs like “Northern Attitude,” “Stick Season,” “Homesick,” and “The View Between Villages” became touchstones not because they chased universality, but because they refused it – grounding big, shared emotions in hyper-specific places, memories, and moments. In naming the resentments, affections, and contradictions of small-town life, Kahan gave listeners permission to sit with their own, turning private ache into something communal.

In the time since Stick Season reshaped his career, Noah Kahan has been living inside the very contradictions he once wrote about from a distance. The album’s success opened doors he’d never imagined – larger rooms, louder crowds, a widening public life – even as it pulled him further from the grounding spaces that first gave those songs their shape. Fame didn’t resolve the tension between past and present; it magnified it. The farther Kahan traveled from home, the more clearly he felt the distance growing – between who he was, who he’d become, and the people and places that once felt inseparable from his sense of self. That disorientation, that whiplash between arrival and alienation, forms the emotional backbone of what comes next.

“The last five years have been the single most challenging, complicatedly beautiful, and life-altering of my career,” Kahan recently shared, reflecting on this moment of transition and reckoning. “I was somewhere I understood, and suddenly I was somewhere completely foreign. I was living in the opportunity I always wanted but felt disoriented and unsure of whether I deserved it. Writing for this album was a balancing act of trying to go back in time and move forward in the same moment. Songwriting has always been the way I reflect on my life, and I hope these songs show you a glimpse of what this journey has looked like.”

That tension – between past and present, familiarity and estrangement – sits at the heart of “The Great Divide,” a song born from the inner reckonings that arrive after the noise dies down. After years of movement and momentum, of living out of suitcases and soundchecks, Kahan found himself staring across an emotional distance that couldn’t be crossed by proximity alone. Success had given him everything he once imagined, yet it had also reshaped the geography of his life – stretching relationships, warping time, and reframing memories that once felt fixed and shared. People who grew up side by side now occupied different emotional worlds; shared history no longer guaranteed shared understanding.

“The Great Divide” lingers in that uncomfortable in-between space – not at the moment of departure, and not at the moment of reunion, but in the silence that follows.

It’s a song about the things we carry long after the conversation ends, about the words we rehearse but never say, about realizing too late that we misunderstood the weight someone else was carrying. Kahan doesn’t write from a place of accusation or closure here; instead, he writes from the ache of hindsight, reckoning with how easily closeness can dissolve when life pulls people in different directions.

That emotional distance is rendered not as abstraction, but as lived experience – childhood bonds reduced to fragments, spiritual fear tangled with guilt, affection braided tightly with regret. The divide in question is not singular or symbolic; it’s layered and cumulative, formed by time, ambition, silence, and survival. In facing it head-on, Kahan isn’t trying to bridge the gap so much as name it, to stand at its edge and finally articulate what it feels like to look back across a life that no longer runs parallel to the one you left behind.

Speaking with PEOPLE, Kahan framed “The Great Divide” as an outgrowth of that internal reckoning. “My life had changed so much and I felt this real gap growing. I started to think about divide in my life, whether that was the divide between me and this old version of me, or me and the people that I used to know growing up, or the people that are in my life that I’m still trying to keep a relationship with.” For Kahan, the song emerged from imagining what might happen if those distances could be crossed – or at least acknowledged. “The Great Divide” took shape, he says, as he wondered what he’d say if those people were suddenly standing in front of him, ready for a conversation that never quite happened.

That imagined conversation – the one that never quite happens – is where “The Great Divide” begins. As Kahan explains, “This song in particular is really about two people who grew up together, but maybe didn’t know each other as well as they thought. A lot of my life recently has been realizing the things I wish I could have said to people and the things I wish I could have done differently, and so this song is kind of just an expansion of that.” Rather than staging a dramatic confrontation or offering a tidy resolution, Kahan writes from the middle of the silence itself, excavating memory, guilt, and misunderstanding line by line. The song opens not with nostalgia, but with disillusionment, reframing shared history as something thinner and more fragile than it once appeared:

I can’t recall the last time that we talked

About anything but looking out for cops

We got cigarette burns in the same side

of our hands, we ain’t friends

We’re just morons,

who broke skin in the same spot

It’s a bracing introduction – one that dismantles the romanticism of growing up together by reducing it to recklessness and proximity. What once felt like intimacy is recast as coincidence: Shared scars without shared understanding. The cigarette burns become shorthand for a bond forged through damage rather than care, a connection built on surviving the same environment rather than truly knowing one another. When Kahan admits we ain’t friends, it lands less as accusation than as realization – a painful reassessment of what that closeness ever really meant.

That reckoning deepens as the verse turns inward, shifting from observation to self-awareness:

But I’ve never seen you take a turn that wide

And I’m high enough to still care if I die

So I tried to read the thoughts

that you’d worked overtime to stop

You said, “f*** off,”

and I said nothin’ for a while

Here, distance isn’t just emotional – it’s existential. The widening “turn” signals a life path that diverged beyond recognition, while Kahan’s admission of still caring if he dies exposes a fragile, suspended moment of clarity. He wants to understand, tries to read what was never offered freely, and is met with rejection. The response – “I said nothin’ for a while” – is devastating in its restraint, capturing the paralysis that follows when the moment for honesty passes and silence takes its place.

That silence echoes into the pre-chorus, where regret gives way to empathy:

You know I think about you all the time

And my deep misunderstanding of your life

And how bad it must have been for you back then

And how hard it was to keep it all inside

This is the emotional pivot of the song – the point where judgment dissolves into belated compassion. Kahan acknowledges not just distance, but failure: A deep misunderstanding of what the other person was carrying. The lines are haunted by hindsight, by the realization that closeness doesn’t guarantee insight, and that suffering can exist in plain sight, unnoticed, for years.

That empathy culminates in a chorus that functions like a conflicted blessing – tender, bitter, and unresolved all at once:

I hope you settle down, I hope you marry rich

I hope you’re scared of only ordinary shit

Like murderers and ghosts and cancer on your skin

And not your soul and what He might do with it

The chorus reframes Kahan’s empathy into something far more complicated than forgiveness. On its surface, it reads like a well-wish – even a kindness – but beneath it lives a knot of fear, resentment, and unresolved concern. When Kahan sings, “I hope you settle down, I hope you marry rich,” the sentiment lands with a bittersweet irony, less aspirational than defensive, as if wishing safety and stability from afar is the only remaining way to care without reopening old wounds. What follows sharpens that tension further: His hope that the other person might fear only “ordinary” threats – murderers, ghosts, illness – exposes a deeper anxiety about what truly haunts them. The line “and not your soul and what He might do with it” introduces a spiritual unease that cuts to the bone, suggesting that the divide between them isn’t just emotional or geographical, but moral and existential. Faith, guilt, and inherited fear loom quietly in the background, shaping the distance between two people who once shared a world but learned to fear different things.

Crucially, the chorus doesn’t resolve that fear; it circles it. There’s no claim of understanding here, no tidy absolution. Instead, Kahan lets the blessing remain fractured – part hope, part worry, part confession – capturing the uneasy truth that caring for someone from a distance can still mean carrying their demons alongside your own. In that unresolved tension, “The Great Divide” finds its emotional center: A song not about reconciliation, but about learning how to live with what was left unsaid.

If the first verse is about proximity mistaken for intimacy, the second verse widens the lens, tracing how that divide quietly solidified over time.

The song’s geography opens up alongside its emotional scope as Kahan contrasts two paths moving in parallel but never quite together: “You inched yourself across the great divide / While we drove aimlessly along the Twin State line.” One person crosses something deliberate and life-altering while the other drifts, suspended in motion without direction. The “Twin State line” becomes a subtle metaphor for connection and separation at once – close enough to touch, yet fundamentally misaligned. That sense of missed understanding deepens as Kahan revisits memory and miscommunication: “I heard nothing but the bass in every ballad that you’d play / While you swore to God the singer read your mind.” What felt revelatory to one person passed by unheard by the other, not out of malice, but limitation – a devastating admission of selective listening and emotional blindness. The verse closes with a reckoning that is both personal and moral: “The world is scared of hesitating things,” he realizes, and it was “shitty and unfair” to stare ahead as if everything was fine. Here, the divide is no longer just emotional or relational; it’s shaped by passivity, by fear of pause, by the harm of not paying attention soon enough.

You inched yourself across the great divide

While we drove aimlessly along the Twin State line

I heard nothing but the bass in every ballad that you’d play

While you swore to God the singer read your mind

But the world is scared of hesitating things

Yeah, they only shoot the birds who cannot sing

And I’m finally aware of how shitty and unfair

It was to stare ahead like everything was fine

As “The Great Divide” moves toward its close, Kahan distills the song’s emotional sprawl into its most vulnerable admission. The bridge arrives as a confession rather than a climax – “Did you wish that I could know / That you’d fade to some place / I wasn’t brave enough to go?” – reframing the divide not as abandonment, but as a failure of courage. What separates them isn’t just time or belief or distance, but the inability to follow someone into the unknown when it mattered most. From there, the chorus returns again and again, no longer just a conflicted blessing but a mantra Kahan clings to – an attempt to care from afar without reopening wounds, to wish peace while accepting estrangement. Each repetition deepens its spiritual unease, the fear of “what He might do with it” looming larger as faith, guilt, and inherited belief systems reveal themselves as part of the fracture.

The outro sharpens that reckoning further: Hopes turn more pointed, more urgent, as Kahan imagines rebellion (“throwing a brick into stained glass“), honesty, and rest – not as things he can offer, but as things he wants for someone he can no longer reach. In the end, “The Great Divide” doesn’t resolve its tension; it names it. The song closes not with reconciliation, but with recognition – an acceptance that some distances can be understood, honored, and carried, even if they’re never crossed.

Taken as a whole, “The Great Divide” doesn’t mark a departure for Noah Kahan so much as a sharpening of focus. It reintroduces him not by softening the edges carved by Stick Season, but by pressing deeper into them – louder, more volatile, and less willing to look away.

Where Stick Season traced the resentments and affections of home, “The Great Divide” confronts what happens after you leave: The emotional distances that widen in your absence, the relationships that don’t survive growth, the versions of yourself you can no longer return to. It’s a song that carries the same radical honesty that has defined Kahan’s work from the beginning, but delivered here with new urgency – electric, combustible, and unafraid of its own messiness. In that sense, “The Great Divide” feels less like a reset and more like a reckoning: A declaration that the next chapter won’t resolve the questions Kahan has been asking, but sit with them more loudly, more honestly, and more fully than ever before.

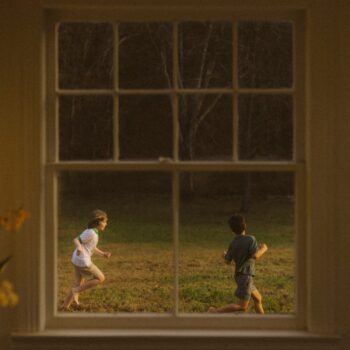

That expanding emotional world extends beyond the song itself and into its visual storytelling. The accompanying music video, directed by Parker Schmidt, leans into the same sense of accumulated history and unresolved distance, translating the song’s interior reckonings into something physical and lived-in. As Kahan explained, “For this album and for this song in particular, there’s so many characters and so much narrative and complexity to the story that I wanted to find a way to bring the two worlds together. Such a big part of the writing process for me is honoring the stories.” Set largely in a single, intimate location, the video allows time to pass visibly – characters age, relationships strain, and the weight of shared pasts becomes impossible to ignore. “The director Parker and I have talked about how to do that, and one of the ways we’re doing it is by having these different characters age through time in this one really cool, intimate gas station location, as an allusion to the evolution of the friendship and the kind of conflict that these two friends and this friend group got into, which is what the song’s about.” It’s less a literal retelling of the song than a parallel meditation on it, reinforcing the idea that “The Great Divide” isn’t about one moment of rupture, but about what happens when time, silence, and unspoken truths quietly reshape everything.

Rage, in small ways

Did you wish that I could know

That you’d fade to some place

I wasn’t brave enough to go?

I hope you settle down, I hope you marry rich

I hope you’re scared of only ordinary shit

Like murderers and ghosts and cancer on your skin

And not your soul and what He might do with it

If “The Great Divide” introduces the emotional stakes of Kahan’s next chapter, the album that shares its name expands those stakes outward – from one fractured relationship into a constellation of people, places, and past selves that continue to shape him. Where the song lingers in the aftermath of a single, unfinished conversation, The Great Divide as a record appears to grapple with the cumulative weight of distance itself: The separations that form over years, the voices that go unheard, the parts of home that remain unreachable no matter how far you travel. Rather than attempting to resolve those distances, Kahan seems intent on standing inside them, tracing the outlines of what’s been lost, what’s been carried forward, and what still demands to be named.

“From a long silence forms a divide, a great expanse demanding attention,” Kahan wrote of his upcoming album. “I stare across it. I see old friends, my father, my mother, my siblings, my younger self, the great state of Vermont. I want to scream these feelings, to gesticulate wildly at the figures on the other side, but my voice has grown hoarse and muted after years of climbing a ladder towards the wild, spiraling dreams that have materialized in front of me. Instead, I wrote them down next to a piano in Nashville, next to a pond in Guilford Vermont, in a legendary studio in upstate New York, on a farm with a firetower in Only, Tennessee.’

“The songs are the words I would say if I could. They are the fears I dance with in the moments before I drift off to sleep. The music here is my best attempt to delve deeper into the people, places, and feelings that have made me who I am. I am grateful for all of it, for all of you, for listening to them, if you choose to do so.” In that sense, The Great Divide isn’t just an album title or a thematic motif – it’s the space Kahan has learned to stand inside, listening carefully to everything on both sides.

In its final moments, “The Great Divide” lands less as a conclusion than a commitment – to tell the truth even when the truth doesn’t tie itself into a bow.

It’s a song about distance, yes, but it’s also about what survives distance: The lingering tenderness, the buried guilt, the spiritual fear, the stubborn hope that someone out there is finding peace even if they’ll never be reached again. That’s what makes it hit so hard – not the drama of separation, but the humility of hindsight, the way Noah Kahan writes from inside the unanswered question and lets the ache stay human instead of turning it into spectacle.

I hope you threw a brick right into that stained glass

I hope you’re with someone who isn’t scared to ask

I hope that you’re not losing sleep about what’s next

Or about your soul and what He might do with it

As the first chapter of The Great Divide, the title track feels like a vivid re-entry – sonically bigger, emotionally bolder, and thematically expansive, without losing the intimacy that has always defined his work. It reintroduces Noah Kahan not as someone searching for meaning, but as someone willing to sit in it – to honor the stories, name the gaps, and sing toward the people and places on the other side of the silence. If this is what opens the door, it’s hard not to feel the weight of what’s coming next: An album poised to turn private distance into shared language once again, and to remind listeners why they fell in love with Noah Kahan’s songs in the first place – not because he offers answers, but because he sings the truth from inside his own uncertainty, and lets that be enough.

— —

:: read more about Noah Kahan here ::

— —

:: stream/purchase The Great Divide here ::

:: connect with Noah Kahan here ::

— —

Stream: “The Great Divide” – Noah Kahan

— — — —

Connect to Noah Kahan on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Patrick McCormack

:: Stream Noah Kahan ::

© Patrick McCormack

© Patrick McCormack