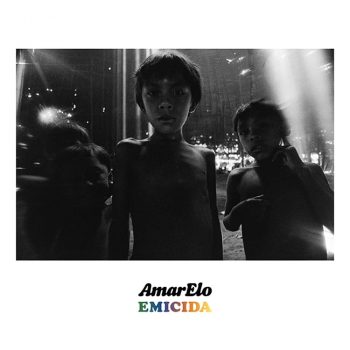

Brazilian multi-hyphenate and Latin Grammy-winning artist Emicida talks Atwood Magazine through his Netflix documentary AmarElo: It’s All For Yesterday, all the stories that led him there, and what his dreams of a better Brazil look like.

•• ••

When studying the hero’s journey in literature, some of the happenings seem so impossible that we struggle to believe that any semblance of that story could actually happen in real life. It just so happens that sometimes life can be even more beautiful and potent than literature.

Emicida, born Leandro Roque de Oliveira, has lived somewhat of a hero’s journey throughout his 35 years of life. Born in São Paulo, Brazil, Emicida was raised among poverty and violence, and grew in popularity by participating in rap battles until the release of his first official single, “Triunfo”, in 2008. 12 years later, the man who never stopped dreaming and believing a better reality was possible is now the true definition of multi-hyphenate. The Brazilian artist is a full-time rapper, singer, songwriter and entrepreneur, and also doubles as a children’s book author, TV host, podcaster, and the star of a Netflix documentary.

Emicida steps into these different roles naturally, using every single medium he enters to educate and incite revolution through his words.

AmarElo is the name of the record which spawned what may be Emicida’s biggest movement to date. Released in 2019, AmarElo is the home to several worlds, sounds, voices and stories. Emicida’s own experiences, dreams, friends and family are featured throughout the album, but from the birds chirping in the early morning in “Principia” to Ibeyi’s powerful voices clamouring for freedom in “Libre”, the album is nothing short of universal.

Watch: “É Tudo Pra Ontem” – Emicida ft. Gilberto Gil

The album’s richness couldn’t be denied, and just as naturally as Emicida went from rapper to one of the most influential voices in Brazilian culture, AmarElo transitioned from being an album to existing as a multimedia movement. AmarElo Prisma, a podcast hosted by Emicida, dissects paths to bring about a collective well-being and change. AmarElo: It’s All For Yesterday, Emicida’s documentary released in December, is the culmination of all he’s experienced and learned on his own hero’s journey. In it, he traces his own story – all leading up to a concert at São Paulo’s historic Theatro Municipal – and masterfully tells the story of Brazilian culture via the people who actually shaped it.

There’s little that does justice to just how potent the documentary is as it re-writes Brazilian history and aims to make Brazil’s future brighter. Very little does justice to Emicida’s words as well as he describes the process of making the documentary and all the research that led helped its creation. Emicida talked Atwood Magazine through his Netflix documentary AmarElo: It’s All For Yesterday, all the stories that led him there, and what his dreams of a better Brazil look like.

•• ••

Watch: AmarElo: É Tudo pra Ontem – Official Trailer

A CONVERSATION WITH EMICIDA

Atwood Magazine: Firstly, I wanted to congratulate you for the whole AmarElo universe - the album, podcast, documentary, the movement it’s become. I thought the way in which you traced your own story with Brazil’s history, especially highlighting all the Black people who were silenced and ignored throughout history but contributed so much to our culture, in the documentary was incredible. My first question is, while writing the script and coming up with the documentary’s concept, where did the idea of meshing your story and your show at São Paulo’s Theatro Municipal - which in itself is already momentous - with Brazil’s history and our culture come from?

Emicida: Thank you. The first thing I can tell you is that around here we’re always having these kinds of conversations, so naturally this was somehow reflected in the documentary. It’s interesting because a lot of people are watching the movie and thinking “Wow, they did so much research”, and in fact we did do research but our research was more focused on organising dates and numbers so we didn’t get anything wrong. Up until the last minute Fióti (Emicida’s brother and manager) wanted to die because the movie needed to be finalised and I was like “Dude, I need to finish reading this last book about 1938, I need to finish this just so we can reach a certain conclusion”, and [Felipe] Choco, our researcher, was saying “We need to analyse this other perspective” and Fióti was pulling his hair out asking “How much time do you need to finish reading this book?”. We wanted to be very faithful to the history. Janeci, who did the soundtrack, said something really beautiful during the mastering. You know when sometimes you’re watching a project’s final cut and you breathe out and say something like “How beautiful!”? Jan said something amazing, she said “I’ve never seen something like this in my life because it’s all real!”. It looks fictional! Toni [C.] (screenwriter) and I, because of other projects we’ve worked on, incorporated the hero’s journey into the movie. There is this structure of leaving your home, fighting the monster, having a master to guide you, not believing in yourself and then returning home bigger and better than you were before. There’s a lot of Perseus’ myth in it, and we have conversations about these things all the time here.

We see ourselves as the successors of the people we’ve referenced in the movie. Personally, I’m so happy people know who I am, but I think people will only truly know who I am if they know where I come from, which is what happens to all of us because then I won’t make any judgements about you because I know your story. I think us sharing this story – and maybe this is what makes the movie unique – is that these characters have all been cited in other documentaries and other storytelling forms, some less popular, and maybe for the first time we’ve inserted them as the gravitational centre of a story. Samba isn’t a story that’s a part of all other stories, samba is a character [in our movie]. It’s more than a musical movement, it’s a way of life, a way of seeing the world that continues the legacy of other ways of seeing the world that were brought here by African people who were enslaved. This other Brazil is the epicentre of all happenings which we refer to as Brazilian culture, and the conclusion I draw, which is the same as the one Lélia Gonzalez defends, is that Brazilian culture was created by African people. I believe that under so much violence that was being perpetrated by colonisation in our recent history, the one element which civilised our country was the contribution of the kidnapped African people.

You spoke a little bit about your place in the legacy of all the characters you highlighted in the documentary. I wanted to know how you see yourself - Emicida and Leandro - inserted in the timeline you drew up and the legacy you’re going to leave in our culture. Today, undoubtedly, you’re one of the most influential and important voices shaping our culture, so you’re already making your mark, and I wanted to know how you perceive all this.

Emicida: Look, Nicole, the truth is that I don’t think about this. It doesn’t mean that I’m completely alienated to the influence I have, I worry about what I say and how my words reach people. I’m always reflecting upon how being born Black in Brazil and looking to get to know your history is almost like a relay race. One person comes running with the baton, hands you the baton, and then you’re off running. During our upbringing we aren’t taught everything and given the baggage that we share on the documentary, so we don’t know if we should run take off running without the baton or turn back and look for the place where the baton was lost, then we keep floating in this limbo in this non-place of what we are in the Brazilian experience. Somehow, the people we mention in the documentary handed me the baton – even if the baton is subjective – but this reached me via music, text, literature. It reached me and I feel like I’m in the possession of the baton. Now, what do I do? I channel all my energy, all my best thoughts and feelings and run, run as much as I can so I can pass the baton onto the next generation. I see myself as a link between it all.

Earlier, during all these interviews I’m doing today, a journalist told me he felt like there should have been more Emicida in the documentary, as if the movie should focus more on me. But I think the movie does totally talk about me, because the idea is that it’s a tree with tons of fruit and I’m one of these fruits. This is a flaw, I could be more of a personalist (laughs). But the truth is that I don’t want to position myself as this story’s owner, quite the opposite, I want this story to be shared exactly how it is now, I’m just one single thread that’s telling it and there are other ones. For example, in the conversations I have with my friends and family, if you ask anyone about the movie they’re going to answer you through a different perspective. The women are going to tell you a lot more details about Lélia (Gonzalez), and they helped us shape the beautiful and sensitive perspective where we talk about Lélia from the start and show her in all her magnitude and power in the movie. If you ask the left-swinging people, they’re going to talk in depth about the influence of the Black perspective and movement in the social movements. The more conservative ones will focus on the Black influence, which also had its fair share of conservative members, you know?

There was one thing I saw which is an extremely Brazilian paradox. We found a newspaper from 1938 and it had the most bizarre cover in history, Nicole. Something that only Brazil can produce. The headline was “25 Thousand People Salute Hitler”, this was the biggest one, and the headline under that was “50th Anniversary of the Abolition of Slavery will Celebrate the Legacy of Zumbi dos Palmares in the Centre of São Paulo”. It’s the same country!

Yes. That’s crazy.

Emicida: I found this cover and sent it to our group chat and said “Guys, this is the complexity level which we should keep in mind [while making the movie]”.

In Brazil things are always on another level.

Emicida: Completely!

And there’s also the factor that, due to our culture being so diverse and complex, we have to be able to digest all of this extremely complicated information and then try to explain it to others in a way where people won’t feel overwhelmed by what we’re saying. If you think about the extremely low education levels in the country, to be able to make a message like this accessible and democratic, especially considering how multi-faceted and complex our society is, is so difficult and I thought you did that masterfully.

Emicida: This is also something we owe to the African people, they’re the masters of oral tradition. Maybe this form of us telling our story is directly owed to a writer called Amadou Hampâte Bá, he has a book called Amkoullel: The Fula Boy about his life, and he was the person who made UNESCO recognise the value of orality. Influenced by him and [Ailton] Krenak (a Brazilian writer and environmentalist), who I’ve become closer to in the last few months, we managed to create and tell this story in way that’s first of all affectionate and inviting. Typically these conversations are approached in another manner, this conversation is brought to the table as if it has to cause conflict and in fact it does in a variety of ways, but we’re looking to inform people so that we can use this as a starting point to create a conversation. Affection is a great way to do this, and AmarElo’s atmosphere already wholly incorporates affection.

It’s really fucking cool to think about the way my grandmother, Dona Emericiana, told me stories about captivity and slavery. Her stories weren’t about 1888 (the year slavery was abolished in Brazil), but she kept these stories so vividly and close to her heart because the only way they had to pass their stories along, due to structures which were out of their hands and also due to illiteracy, was through talking and telling stories. When you’re talking, you rarely ever take these conversations to a more serious tone, especially when you consider popular culture and our people who are from the streets. You never see it through the academic lens which is typically very arrogant, where I’m trying to prove to you that I’m well-read and instead of building a bridge, you end up building a wall, people feel embarrassed. I think a lot of the path Brazil has taken is due to this, we have to be very careful with information that segregates. People discover a water well but they don’t share the water they found, because the fee to access that water is to worship me as an academic. And no, that water exists to quench people’s thirst. So we found a well and we’re sharing the water we found with people the same way my grandma used to speak to me. She used words that drew from people from Cabo Verde, which then sounded like the language of the enslaved people from Minas Gerais, and all of this was put together with such love so that I could take it to heart, that I wanted to share it with the same affection which they put into it for me. It really struck me, and I share it with love and affection so that it can strike people and they can take it to heart too.

The most important thing of all: with the best of intentions, people say “It’s a good documentary about the story of Black people”. No! It’s not the story of Black people, it’s our story! It’s Brazil’s story and they stole these pages from your history book! We’re just re-inserting those pages in our book because if we were introduced to our full history, our conception of who we are and what it means to be Brazilian would be completely different. We’d be in another place both intellectually and as a society.

They do say that history is written by the winners. If history was written by the oppressed, it would be a completely different history. Anyways, in the documentary you mention that “Principia”, AmarElo’s opening track, soundtracks a dream. In an interview you said that we need to allow ourselves to dream again otherwise we won't be able to build a better Brazil. How important are dreams in your life?

Emicida: I see dreams as a huge compass. I come from extreme poverty and the only thing I had was my dream, my faith. My elders used to say “pra baixo todo santo ajuda” (A Brazilian saying which essentially means that going downhill is easy), who has never heard this? I really latched onto this phrase because if I don’t believe things can happen, that’s death. This isn’t blind optimism, I work very hard to construct a reality in which life can flourish. Sidarta Ribeiro has a book called O Oráculo da Noite (The Night Oracle) about the meaning of dreams. In the past, dreams were much more important, solid and permanent guiding lights in humans’ lives. Today, dreams are discarded as something childish – believing seems like something worth making fun of – and that shows just how big the abyss in which we find ourselves really is. Someone else I really like, the French anthropologist Philippe Descola, has a book called Beyond Nature and Culture. This book is incredible because it analyses a few indigenous tribes of the Venezuelan Amazon and they manage their crops and agriculture based on their dreams. This is how important a dream is. Our society has detached itself from believing so much that we only believe in a cellphone, in money or in something concrete, but subjectivity is what fills our life with meaning. The more we kill our subjectivity, the more we become disposable gears. I don’t want to be disposable, that’s why I’ll keep on dreaming.

Last question: what is the Brazil of your dreams like?

Emicida: Fuck, you got me there. I think “Principia” synthesises the Brazil of my dreams. What unites us as Brazilians? It’s coming together. We can come up with one thousand ways to think about the origin of our coming together, some very violent and embarrassing. We can look at the history of colonisation and be ashamed of our country’s past, but the fact is that this coming together was real and our history will be lived on forever. What do we do with the way in which our society was formed, this coming together? I think we need to look at all benefits and richness that this country produces, find the places here in which they don’t have access to this richness, and spread this richness around there. Then we can strengthen our country and we can start fighting a miscegenation culture that curses those with darker skin. Miscegenation is a fact, as much as it’s a fact that the darker your skin, the worse your experience is as a Brazilian. We need to be radical in order to make sure our country’s benefits make their way through our whole society, that’s my dream.

— —

Connect with Emicida on

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Jeferson Delgado

:: Watch Re-writing History with Love and AmarElo: A Conversation with Emicida (in portuguese) ::

:: Stream Emicida ::