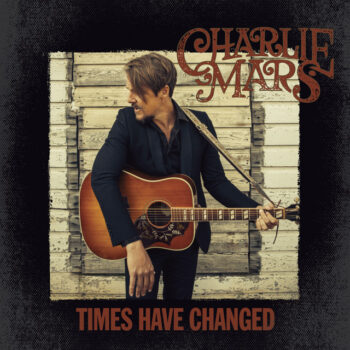

‘Times Have Changed’ is a painting of singer/songwriter Charlie Mars’ new life in the countryside with what he has learned about himself and his expression of music.

Stream: ‘Times Have Changed’ – Charlie Mars

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

There is symmetry between a product and when its producer is human. It’ll have flaws and scuffs, yet you like it. Why? Because it is aged, and it is imperfect, and it has humanity in it.

In the hills of rural Mississippi is Yalobusha County, a place where Charlie Mars now resides. The 49-year-old country folk artist has experienced many lifestyles through all the different places he’s been in. From living in Oxford, Mississippi for the majority of his adult life then moving south to Taylor, Mars slowly left the city until he came to Yalobusha. However, this transition from the city to the country wasn’t as clear-cut as it seems. In fact, Mars even lived in Sweden for some time.

“I would say I’ve had a pretty cosmopolitan life. I lived in New York for four years, I lived in Sweden for a while, and I’ve traveled all over the world.”

Mars describes how he grew up in a small town and wanted to see the world. This album Times Have Changed is his ninth since his first studio album in 1996. With history in the industry and life experience Mars speaks through his album in a different way than before.

“This album is about looking at where I’m from, the people around me and settling in that exploration and celebration in a way that I wouldn’t have when I was 20.”

The album features 10 songs on it with a mix of wit and wisdom on Mar’s past and new life in Yalobusha County. From an honorable mention to his dog Kudzu on “Silver Dollar” to a heartfelt reflection in “Gotta Lotta Love,” to a story involving Jimmy Buffet in “Tahitian Phone”— Mars’ character shines through with a newfound intention.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

He sums up the album through asking a simple question that holds a deeper meaning:

“Would you rather get an email or a letter?”

The majority of people would want to receive a letter. Why? It is tangible — something you can hold onto rather than lose in digital memory. Mars has an affinity for keeping this sense of humanity in his music.

“If you don’t have some humanity connected to the material world, then there’s a spiritual loss. I’m just trying to keep that letter alive.”

With Atwood Magazine, Charlie Mars gives thoughtful insight on his latest album Times Have Changed and the wisdom he’s gained through creating it.

— —

:: stream/purchase Times Have Changed here ::

:: connect with Charlie Mars here ::

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

A CONVERSATION WITH CHARLIE MARS

Atwood Magazine: A lot of the album is inspired by your new home in Yalobusha County and your dog Kudzu. Could you paint a picture of where you’re currently living?

Charlie Mars: During the shutdown I acquired a dog, which turned out to be a highly aggressive protection breed. I didn’t know if he should be in a community of people and my brother had seen this alternative housing option, which was a furnished-out Quonset hut on 40 acres. It’s the middle of nowhere on a gravel road in Yalobusha County and now Kudzu’s very happy. For me, I never lived in the country and that’s been an adjustment from a college town to being here. It’s been about two years and I’ve learned a lot. I enjoy physical labor and with it, you end up knowing the people around you well. They’ve been helping me learn how to manage the land and adjust to this new pace of life.

Before this, I did what any musician would do in a college town—I went out and saw friends and people all the time—I lived right on the town square—a lot of it was a distraction. I mean, you can call it what you want—distractions or things to fill up your time—but now they’re gone. It’s an interesting transition. This album is about looking at where I’m from, the people around me and settling in that exploration and celebration in a way that I wouldn’t have when I was 20.

These are great starting points because looking at the album you see a lot of gratitude reflected in “Gotta Lotta Love” and “Country Home.” Even “Silver Dollar” talks about your neighbor helping you and this community you’ve become a part of. Could you tell me more about this?

Charlie Mars: When you move out into the country, you’re living a similar life to everyone around you and they’re all having to do the same things that you have to. That isn’t necessarily the case when you live in a big city. There’s a certain spirit amongst the people that live in the country that you start to have that in common with. If something goes wrong, you only have a few people that can help you out and it’s nice to have some people on your team, because you’re in it together. One my neighbors has chickens and so he gives me eggs, and I grow food in my garden, and I give him lots of tomatoes and peppers and squash. Something about that is very refreshing.

There’s no American Express transaction where I have to enter a PIN code. Human beings lived that certain way for, from what I understand, thousands of years, and it’s only been in the last 100 years that everything’s different. There’s a blood memory when you start doing certain things, like you have this muscle that you’ve never exercised and when you start to exercise it, you feel rejuvenated, because the muscle is not in atrophy.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

There’s a certain spirit amongst the people that live in the country that you start to have that in common with. If something goes wrong, you only have a few people that can help you out and it’s nice to have some people on your team, because you’re in it together.

I really like that perspective and I remember you talked about needing to disconnect to reconnect with your humanity. Now living in the country, how has this changed your perspective and spiritual journey? How does this play out throughout the album, and even reflection in “Times Have Changed”?

Charlie Mars: I mean would you rather get a letter or an email?

A letter.

Charlie Mars: That’s kind of the whole thing. If you don’t have some humanity connected to the material world, then there’s a spiritual loss where everything devolves into a digital nothingness. I’m just trying to keep that letter alive. There’s a DNA imprint that I feel is being lost and it’s significant to hold onto. It’s meta-physical. That’s the spirit of it, and to deny the spirit is to deny an instinct to preserve value through humanity. There is symmetry between a product and when its producer is human. It’ll have flaws and scuffs. It’s like seeing a wall where the paint is chipping off of it. And you like it. Why? Because it is aged, and it is imperfect, and it has humanity to it. We’re imperfect and we’re aging, and our pain is flaking off. There’s an expression of a person when you get a letter and see someone’s penmanship or when you hold a vinyl record there’s something tangible that you can feel—choices of colors and design. There’s something spiritually unfulfilling about digital technology and apps. We all have to learn how to integrate our lives with that evolution but in my opinion, we’re just a bunch of guinea pigs that have gotten off the path and then in 50 years, there’ll be writing about the bunch of squirrel brains we were.

I love that insight of keeping music timeless. Even in “Country Home” you reflect on unity and gratitude throughout your personal life. I love the line where you say, “My grandfather taught me about the way, the truth, and the life.” Can you tell me more about this forgiveness and grace you sing about along with lessons you’ve learned from a time before technology.

Charlie Mars: My grandparents embodied a lot of things that we just talked about. They grew up in small towns, one side of my grandparents were cattle farmers. They were hard-working and honest people who went to church on Sunday, and lived what they believed in forgiveness, kindness, putting others first and believing that there was something bigger than themselves. Not getting too big for your britches, staying rooted in where you’re from, and honoring your elders. I was just a young, rebellious punk in my teens and 20s. I definitely put some of it on the back burner and thought they were just old fashioned. Most of the time that I decided to ignore their wisdom, I paid a price that was painful. Why was it painful? Because it was wrong. I loved my grandparents, and my parents also and was just humbled. When you’re humbled, you’re willing to listen. I altered my life towards a narrower set of behaviors and in doing that, I experienced a wider, soulful experience that was never negative.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

Well, “Somewhere on a Mountain” is an example of this, and I enjoyed reading your story? You got fired from a breakfast place, right?

Charlie Mars: I believe it was called the “House of Sourdough Pancakes”, and I got fired when I was 20. I was living in Jackson Hole, and it was the summer between my junior and senior year of college. I lived in employee housing and the owner was always making fun of my accent. I probably wasn’t the best employee to begin with. At the end of the summer, he fired me and I was reflecting on that recently when I was in Telluride, Colorado on a mountain. I was just thinking how I had been out west many years before and lost a job. Now here I was, sitting on this mountain in Colorado. And that’s kind of how the song took shape.

The first line says, “I was with my father/ He pulled over by the side of the road/He said you don’t have to go back/You can just hang out.” But you know, I was young and looking for something and looking for a mountain to climb.” I could have stayed close to my family, or I could have stayed in certain relationships, or I could have stayed in some of the things that probably would have brought me a better life. But I didn’t. There’s the prodigal journey and that was just going out and tasting the fruits of trees and realizing that I got to return home.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

It’s awesome how you can reconnect with yourself and the people that came before you and the values they’ve taught you. I also really enjoy your pieces “Don’t You Want to Know Me,” “Cold Shoulder,” and “Just to See you Smile” because you talk about this human condition and the complexities with it. I know you collaborated with Dan Kaminsky and David Bourne – could you walk me through these collaborations?

Charlie Mars: The Dan Kaminsky song started after we met in the Bluebird Cafe. I had just decided to start writing songs with other people in Nashville. At the time, I was trying to find a way to tour less because it was putting a strain on my personal life. Dan Kaminsky was the first person that I ever wrote another song with, and we wrote that song in one sitting. I also know that Alison Krauss recorded it because he played in Union Station with her. I never heard the version that she recorded so maybe it’ll come out but that was really cool.

“Don’t You Want to Know Me” is about having been in some relationships and just commenting on what can happen for one to be good, and through that actually knowing somebody. That line, “I’m tired of living in my head, I want to love you from my heart instead”. Anybody who’s ever been living in their head, it never seems to be that pleasant for people. Living from their heart, it seems to bring that fulfillment.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

That desire for vulnerability is broken down really well. “To See you Smile” was written with David Bourne, correct?

Charlie Mars: Yes, he was somebody that was a part of a lot of the journey the last five years of my life. I slept on his couch in Nashville. He ended up getting married and had a child, and I moved through some things. I used to smoke pot a lot and I gave that up. There were a lot of things I was doing to cope that I was able to let go of. One of the things that happens when you clear up is you realize that there are people along the way that are gone now. You don’t know when someone is leaving your life and that’s what the song is about.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

Hearing you talk about that really brings the sense of humanness back to the song. You sing “Jesus change this wretched heart of mine” and acknowledging how things change and people with it. To close, I want to go into your stories with “Fat Dad” and “My Tahitian Phone” — can you tell me what lead you to these pieces and producing them?

Charlie Mars: Growing up in the South, I’ve known a lot of guys who are like Tony Soprano meets Santa Claus. They got a lot of swag, they’re flexing hard, and you love them for it. Every region and every cultural group can relate in a way. I played it for my Mexican friend and the dad goes, “El jefe!” If you’re Italian you have “The Godfather”, if you’re Mexican you have “El Jefe” and if you’re from the South you have “Fat Dad.” When you see people with big boats or flying planes it’s hard not to be like “I wish I had a boat or plane.” It’s not a painful envy but I think “Fat Dad” and “Tahitian Phone” are both like ‘I’m down here and you’re up there, and I wish that I was up there.’ But once again, it’s knowing that won’t bring me happiness. It’s like a shiny object in front of a baby, and you wave it in front of him and he wants it. It’s knowing that but also celebrating the fact that someone else is there. Like I’m down with Jimmy Buffet or the “fat dad.” I didn’t want the album to be melancholy, so I had to lighten it up.

Jimmy Buffet is from Mississippi and the cast of guys that inspired “Fat Dad” from the people that I know. The guy from the “Fat Dad” cover is one of my friends whose made it in life and he’s holding a fish on a boat. In life I want to succeed and strive to be like those guys, but that’s not really my ultimate goal. It’s to represent myself emotionally in song and then hopefully make enough money to keep doing it again.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

The writing in “Fat Dad” is really satirical and I liked looking at the lyrics.

Charlie Mars: It’s written from his daughter’s perspective; you know they’re rolling with their fat dad and just talking about it. “When we roll, we be bangin’ Lil Uzi/Headin’ to a town down in that SEC/Daddy’s got a box in the stadium/So mama could have a bathroom and I could have a colored TV.” If you’re from Mississippi and the South everyone knows those characters.

That’s awesome, I enjoy hearing about the inspiration behind this. Going back to “My Tahitian Phone,” could you go more in detail about the story behind that?

Charlie Mars: Well, I had received a call from Jimmy Buffet because he had wanted me to play him in his Broadway musical. He started with “Well I’m from Mississippi and you’re from Mississippi, what else ya got?” and he was kind of a bullet, and I admired that. Anyways, he told me to call him back on his Tahitian phone because he was in Tahiti at the time. And I was thinking, ‘Well I wish I had a Tahitian phone’. As a musician who looks up to someone like Jimmy Buffet who has millions of dollars, I sing “Oh Jimmy, I know it sounds funny/But it’s a good thing you can’t see the other end of this phone/’Cause you’d find yourself a middle aged man/Sleeping in the back of a van/Trying to save money, start a family, and find a home.” So, it’s that reflection on ‘Hey you have all this, want to spare some for me?”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

`

That’s such a cool story and interaction. I love how that inspired your song. Well, if there’s anything else you’d like to talk about or future shows, feel free to!

Charlie Mars: Nope, you covered pretty much everything.

Well, I enjoyed chatting with you and learning more about the album. Thank you for your time, Charlie!

Charlie Mars: No problem, have a good rest of your day. Goodbye!

You too, goodbye.

— —

:: stream/purchase Times Have Changed here ::

:: connect with Charlie Mars here ::

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

— — — —

Connect to Charlie Mars on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© David McClister

:: Stream Charlie Mars ::

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

© David McClister

© David McClister