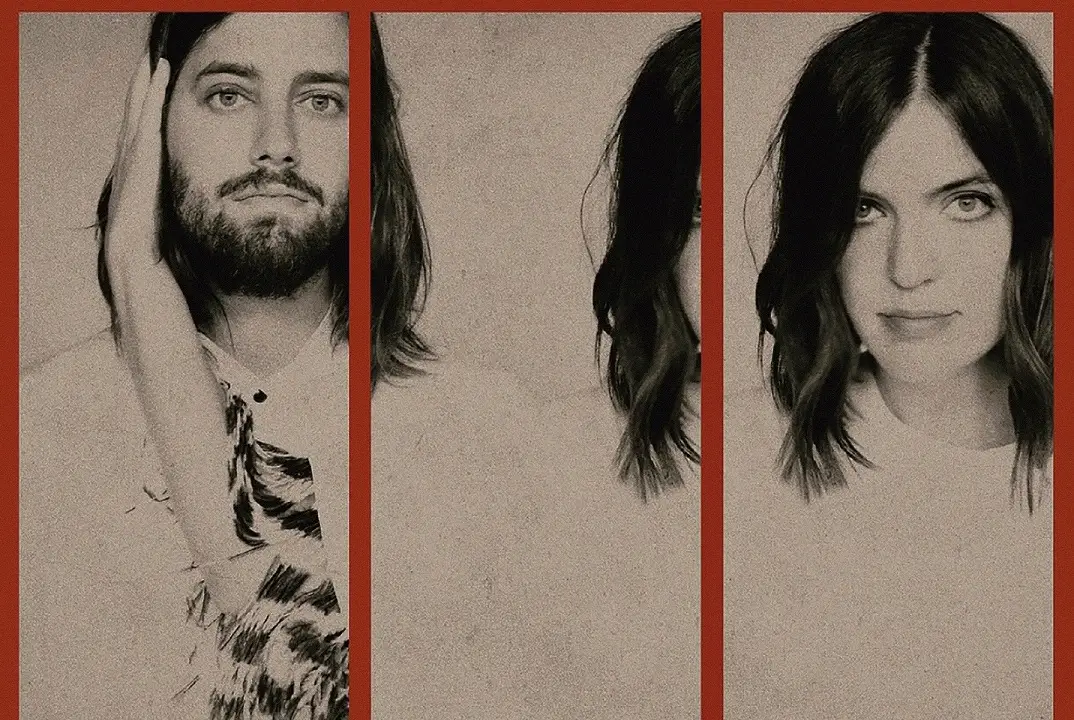

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to speak to R. John Williams of Faded Paper Figures about his life and his band’s new album, Relics, set to drop on August 5th. It’s a mature fourth album: their sound takes on a new depth and complexity of emotion. It’s good for late nights, long drives, and shutting the world out for time to think. If you like what FPF has put out there so far (which you can check out on their MySpace here and on their SoundCloud here) and are interested in hearing them take it further, then I think this album is worth looking into. You can preorder the album now at PledgeMusic.

I spoke to Williams about the ins and outs of his band’s bi-coastal creative process, their busy personal and professional lives as they intertwine with their music (John is a professor of English at Yale; Heather is in medical residency, and Kael writes music for a Los Angeles production company), and how music transcends analysis as an art form.

This is your fourth album, right? In your opinion, what makes it different than the rest?

There are things on it that will seem more ambitions or perhaps more intense or emotional than other albums we’ve done — that’s maybe three or four of the songs — but I think many of the others will seem recognizably within the same genre we’ve been working with so far. We’re hoping that it kind of pushes out a little bit of our comfort zone, so we spent a little bit more time and energy trying to do something that would feel new and exciting but at the same time keep everyone who’s been following us throughout the years happy with some of the same music as well.

Is there anything about it that’s different to you guys personally, or is it just what you said, a little bit outside of your comfort zone and a lot of just sticking with what you’ve been doing?

I think that’s a good question, and it’s probably some of both. When I talk about sort of pressing the boundaries, I’m speaking mostly in terms of the sound but I think also, you know, lives change and people become different people, and some of that happened between the last album and this one, perhaps more so than usual for some of us. So I think that had an important part in forcing us to think a little bit more about what the songs would mean, and what exactly we were doing with the whole process of songwriting. Yeah, I think probably some of both.

Would you be open to talking a little bit about both what’s happened in you all’s lives, and also how you feel that’s affected your music?

Well, sure, um…obviously one of the big things that happened to the band was that Kael and Heather had a baby, and it turns out that there was kind of a special challenge for them because their baby has dwarfism. He’s the most adorable, wonderful human being you could possibly imagine, but it brought about some interesting challenges for them as new parents, and on top of that just kind of trying to manage their lives and their day jobs and continuing to write music and so on.

So there’s that, of course, and then there’s the continual kind of evolution in terms of religion and philosophy that I think for most of us has grown increasingly progressive. . . . We don’t think a lot as a band about “well, what’s the message of this album going to be?” but we kind of all know where we’re at when we talk about other things, so it kind of ends up infiltrating in interesting ways the songs and the phrases, you know, [and] what we try and get out there.

Thanks for sharing that.

Yeah I hope it’s cool with Kael and Heather that I share that with you … but it’s not like it’s private information; he is a genuinely adorable kid. But you know, the kid had to have this special surgery like literally the week before we were gonna start mixing, and everyone’s nervous — and glad that he could have the surgery, for his future — but stuff like that takes a kind of emotional intensity when you come down to actually creating the music, because you feel like [you] kind of need to really believe what you’re saying in some way. I guess in some ways that’s my responsibility because I’m the main lyricist of the band.

With such busy lives, how do you find the time toe keep making music? What makes making music worth it?

Right. Well, the last question is the easiest one to answer, which is that for all of us, the music is like life itself. . . . I don’t think this is a unique experience, I think that many normal, average human beings like us are completely transformed by music, and build our identities around the kind of music that we listen to, and the sounds that really become a part of our core person. And I think that happens for a lot of people; it certainly happened for us. Music was something we knew we wanted to do; even before we met each other, we knew this was something we wanted to do and love.

As far as finding time to make it happen, that’s actually a really challenging thing, because it isn’t just that we have day jobs and everything but there are times that it can just be sort of exhausting to devote the kind of energy that it takes to think about making something that’s new and isn’t just in the sort of typical genre of everything that everyone’s expecting or that sounds like so-and-so. And when you get to a fourth album you also wanna not just sound like yourself. So you start writing a song and you realize “oh, I already wrote this song; that’s the same chord progression I used on the second album” and so then then that takes a little longer to think through, like what can I do that I haven’t done yet.

So, for me, that means late nights. Staying up really late when the house is quiet and the world is gone and asleep and I can think and try out new ideas with the music. I know Kael does that a lot on the engineering side of things; he’s spent countless hours in the studio poring over synth sounds and fine-tuning vocal mixing and things like that.

And then the way we finally manage to put songs together in their most full structure is that I just fly out to Los Angeles every two months and we spend a week and then it’s nothing but the band all week. . . . I literally sleep on the couch in the studio when I go there. So that is pretty intense and can be difficult, especially if I’m visiting Los Angeles and what I really wanna do is go visit the beach but in fact we have this really small window and it’s the only time we can work as a band on this album and it has to happen. So it ends up being a lot of really intense work during those weeklong stretches that happen every couple of months.

But I think in some ways I think it’s beneficial to the band overall to do it like that because we’re not together 24/7 as a band and getting on each others’ nerves and things like that. So we come together, we’re very good friends, we work intensely hard for a week, and then we go home and try and kind of catch up all of the in-between things that have to happen late at night or when there’s a few free minutes during the day. So that’s probably a longer answer than you wanted, but there it is.

Thanks — I appreciate how open you are. It’s cool to hear. I’m getting the window into what’s behind the music that I’m really looking for.

Well, good. We try to be very open about things — like I don’t think we’re the type of band that wants to be so mysterious that it’s not accessible. If anything, we want people to feel like they could come right in and write the songs with us at some point. Not that that’s ever happened, but in the sense of feeling like “oh, yeah, this is the kind of music that I would write if I was going to play with these guys”. And that happens to me a lot, I’ll be like “Aww, God, I wish I wrote that, that’s really really good.” and that’s when you know that you’re really feeling it, when it’s like “that could’ve come from my voice but didn’t.”

I think I’ve had that experience too, where I feel like a song is saying what I would be saying.

Right, and it’s great, like when music does that, it isn’t always because the lyrics are so universal, about totally abstract concepts that really anyone could relate too. Sometimes they’re really quite specific sentiments; something that’s described or even the sound of it and you feel like “this is exactly what I was meaning to articulate but hadn’t fully thought of yet.” And that’s something magical, I remember feeling this way when I was younger and I would listen to the Smiths, and they would sometimes use really obscure references in their lyrics that I wouldn’t know — I had no idea what they were referring to sometimes, but somehow the other aspects of the music connected so well to me that it sort of transcended those specifics, of whatever was in Morrissey’s mind as he was writing it kind of didn’t really matter; it was in some ways my song, even though I didn’t write it, if that makes any sense.

Of course. I feel like it’s possible to have that experience with poetry and other forms of literature too, but I feel that there’s something about the movement of music that I feel like makes music in a lot of ways more transcendent, because you don’t always need to listen to the lyrics.

Yeah, that’s right. And sometimes, it’s not even possible to understand the lyrics, and that’s never bothered me either. I think we try to mix in a way that the words are fairly understandable and you can kind of sing along. But it’s also never bothered me when, like, I’m listening to the Stone Roses, and who knows what that guy is saying half the time, but there was still something about the way the sound came out of his mouth that just meant something to me. Somehow, it was specific to my place and time, and continues to be, even though it wasn’t something that I could always understand, as though it were a clear message about love or sex or whatever that more mainstream pop music is good at. Which isn’t to say I have anything against that either. I’m all for the good dance-or-have-sex song, but that’s to me only a part of the larger spectrum of what music can do for us emotionally and psychologically, philosophically, like in every aspect of human experience music can be there and do something for us.

So in many was it’s the sort of emotive, powerful human experience of creating which is in some ways the antithesis of what i do as a professor. When I’m teaching a work of literature or poetry I can say well this is beautiful but in the end when I’m teaching I’m analyzing. I’m saying well let’s unpack its meaning, try and figure out the historical context, let’s make it mean something additional in terms of my critical lens that i bring to it. but with music you just kind of speak directly to your soul, right? It’s this kind of thing that kind of transcend analysis in some ways, which is one of the reasons I’m so drawn to music as well.

Like listening to music from other people, I really do connect with my own music as well — at least as I’m writing it. Once it’s on a CD and out into the world I really don’t listen to it that much. I mean I like showing it to people and talking about it with people ,but the journey with that song has kind of ended for me in a way and I kind of want to move on to the next thing. So I’ll listen to it the way I would kind of visit old friends in a way, but I don’t listen to our own music as I would if we were writing it. When I’m writing, it’s sort of a compulsion, like I have to really hear every turn of phrase and make sure every word is exactly the word it needs to be and every chord is as it should be, so it’s almost a little obsessive as we’re writing a song, at least for me, anyway — Kael’s the same way, I mean, he’s the guy who will do exactly that thing but with like the sound of the synth patch. He’s like “no this needs an analog, not a digital, or something like that, to get this working, so it’s nice that we both obsess about different parts of the songwriting process. The downside is that it takes us several months to write a song; we’re not one of those bands that just comes together and is like ‘here’s a song! great! done!”

I mean in a few moments, magical moments, that will happen with the basic elements of the song; the structure or the central riff or idea or so on, but even those songs I think we spend some weeks after kind of fine-tuning and recording and re-trying different aspects of it. We’re kind of the endless revisers, in a way.

Yeah. But that kind of “Let’s just slap this together and throw it on a record” doesn’t really seem to be the either the aesthetic or the feel that you’re going for.

You can hear it on the records, right? You can hear it that this band has taken some time and thought out what every part of this song should be. And that isn’t to say that’s the only music I listen to, but that’s kind of what we end up doing because it works for our lives and our band dynamic and the kind of music we want to create, but I’m also good for some early Iron and Wine, just a kid and his guitar in his bedroom recording things; spontaneous rock and roll, I’m all about that as well. I think it would be harder for us to pull that off in some ways.

Yeah, It’s interesting, because both the way in which you create your music (and the music itself) seem to be very deliberate, like you have to make a point of going out to L.A. every two months, cause otherwise it’s not gonna happen, just in the same way that you make a point of every detail — otherwise it wouldn’t happen.

Yeah, well the non-difference there is honesty. You could say “well, this music, because it’s like some other band, because they just put a mic in a room and just recorded a first take or something, that’s really honest.” But I think there are different forms of musical honesty. Like another form of musical honesty is “I have sweated and bled tears and everything else over this song and gone back and re-recorded until it’s this dazzling, well-crafted work of art” that is standing in for us as our music. So that’s a different kind of honesty, right? It’s the honesty of “we’re not going to let this out into the world until we feel completely confident.”

For me, it’s the listenability test. Is it going to be something that people could listen to hundreds and hundreds of times and not feel like “ugh, I’m sick of this, get it out of here” and still feel that this song does enough things in it that you could still be finding new sounds or new connections or new thoughts every time you’re listening to it for hundreds of times then that’s exciting, that’s wonderful if we can get there. And of course you have to recognize as well that there’s enough music in the world today that our music isn’t going to be, like, the music for some people. it’s such a huge, saturated field of beautiful music today that you kind of have to accept that you’re not going to dominate the globe, unless you’re like, Coldplay or something. But that’s a totally different kind of life, it’s a totally different kind of music, in a way, too.

So we’re content, I think, to be in the space that we are, and writing music for the people that we do. And, you know, every once in a while we hear from a fan and it’s just like, “oh, we’re really connecting,” and it’s really cool when we feel like people are listening to it the way we listened to it, and the way we listen to other bands. And then it makes it feel like “Yeah, we should keep doing this.”

![FPF-2014-8[1]](https://cdn-0.atwoodmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/FPF-2014-81-1024x682.jpg)