Fifty years after his death, Gram Parsons’ music and legacy live on.

Twenty thousand roads I went down, down, down, and they all led me straight back home to you…

– “Return of The Grievous Angel,”

Gram Parsons & Tom Brown

He didn’t even make it to the ‘Twenty-Seven Club.’ [1] Gram Parsons – the Georgia Peach, GP – one of the seminal godparents to the broad musical genre we now call Americana, died at the age of twenty-six on September 19, 1973, in a motel room five miles outside the entrance to California’s Joshua Tree National Park from a days-, some say weeks-, long binge on barbiturates, opioids and alcohol. He never had a hit single on the charts. No framed gold or platinum records hung on his walls. Credited on six albums while alive – two solo, four in groups – many of his most powerful recordings were collaborations or covers. His piano and guitar play were adequate; his voice fragile, occasionally choking up or scratchy when strained with emotion or at the outer registers. His live shows could be erratic and sloppy. Neither the Rock and Roll nor Country Music Association’s Halls of Fame have yet to induct him. Occasionally cited as ‘Graham’ or ‘Grahm’ on concert posters or song writing credits, his influence on American music has been profound. He was, in the words of one biographer, a ‘a superstar that no one heard of.’ [2]

Fifty years gone.

Park rangers found his charred remains incinerated in a crudely improvised, gasoline drenched, open air cremation set by some friends near his beloved Cap Rock deep into Joshua Tree National Park a few days after his death, a bizarre story that’s been documented ad nauseam for those of you who care to dwell on the sensational and salacious. There’s even a movie about it. If you want more details, you won’t get them here. The elegy Gram Parsons gets from this writer—after more than a half century listening to his songs; after hiking those trails around Cap Rock more than a few times to get a feel for the solace and beauty that the wildly surreal terrain brought to him; after reading the biographies; after idling my rental car in the parking lot to peek through the windows and gate into the rooms and open backyard of the Joshua Tree Inn on California Rt 62 where he died (yeah, I know, weird) – centers on the “three chords and the truth” of his music. [3]

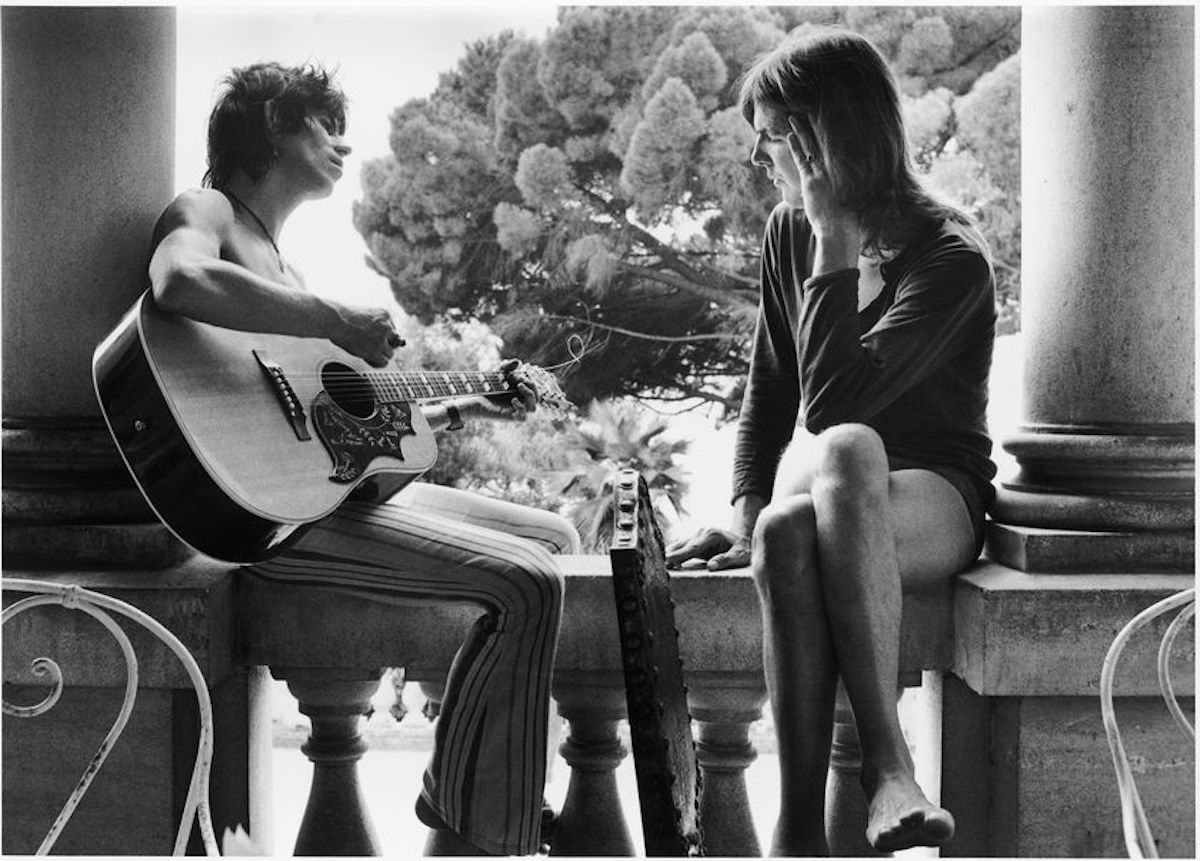

Harvard dropout, short stints on the mid-’60s Florida, New York and Boston folk scenes, founding member of The International Submarine Band (ISB) and The Flying Burrito Brothers’ second incarnation, roundly credited for infusing The Byrds and The Rolling Stones with a more authentic country sound, Parsons’ soulful, confessional and nostalgia filled songs – a pinch of Nashville, a dash of Bakersfield and a light sprinkling of Southern R&B – though not prolific, are often cited as seminal by many of Americana’s top artists. He ignored artistic boundaries and resisted, to a fault, the growing marketing machine that catapulted (and artistically compromised) the careers of many of his peers from what remained of the ‘60s folk-rock scene as the gravitational pull of ‘country’ strengthened. His duets with Emmylou Harris, in the studio and on stage, were pitch perfect examples of the form, often referred to with the same reverence reserved for George Jones and Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn and Conway Twitty. [4]

“ … my feeling is [that] there is no boundary between ‘types’ of music…,” Parsons wrote of the songs he loved to a friend. “I see two types … good ones and bad ones.” He had little company there. The lines between genres – hell, within them – were not easily crossed back then. [5] Country music wasn’t ‘heavy’. We found it crude, unenlightened and artless; out of touch, culturally, intellectually, politically, when set against the backdrop of the anti-war movement and social upheaval characterizing the times. It was the awkward, sometimes tacky and insistent relative from out of town – I’m thinking Beverly Hillbillies here – occasionally interrupting gatherings to cut through all the obtuse chit chat and bullshit, demanding our family stories be told straight and unadorned. We feigned a bemused dismissiveness but sensed something of substance there. When, on the rare occasions that our FM radio stations played Johnny Cash or Willy Nelson, we didn’t turn to another channel.

The burgeoning folk-rock scene brought with it a natural affinity for the music of rural America, especially from the deep South and Southwest, providing new metaphors for its stories and new instrumental possibilities to power their telling. The Stones, Bob Dylan and Neil Young paid their respects. Poco, The Stone Poneys (featuring Linda Ronstadt), The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Little Feat, Pure Prairie League, Loggins and Messina, The Eagles and others made deeper commitments as ‘country-rock’ acts. The music—quite good, sometimes great—was more homage than full immersion, never letting the tether to the steadier sales base of pop-, blues- and folk- infused rock slacken. Other than The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, with Parsons’ guiding the way in the studio and in the control room, there was never a sense of breaking down the divide between ‘real’ country/gospel/R&B and popular music. He smashed through it, ignoring any barriers set by industry execs, radio stations and selective consumers like me whose record collections were essential identity markers to just where in the counterculture we fit. His folk-rock cred gave us license to include the ISB, Burritos and the solo albums on our concrete block and sugar pine shelves alongside the Allman Brothers, Dylan, The Dead, The Stones, and anything with Eric Clapton or Young in it. There was an edge to Parsons’ honky-tonk and boogie styling, especially with the Burritos. [6] The lack of studio polish carried a rawness that gave the albums a ‘live’ feel. [7] You can almost smell the stale beer filtered through clouds of cigarette smoke hovering over the smack of an eight-ball game on pool tables in the juke joints, truck stops and roadhouses which inspired those songs. High Fashioned Queen. Devil in Disguise. Ooh Las Vegas. Cash on the Barrelhead. I Can’t Dance. Pedal steel, mandolin, dobro, fiddle, banjo and keyboards fueling saloon-style arrangements without any lyrical subtext to satisfy our natural leanings toward bohemian cynicism, existential naval gazing, righteous anger and/or political rebelliousness. Good stuff, no question. Enough to keep Parsons, the ISB and the Burritos on any short list in discussions of the emerging country rock scene though nothing to deserve an elegy fifty years on.

The ballads, though. The barstool laments …

Those six albums—the ISB’s Safe at Home, The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the Burritos’ Gilded Palace of Sin and Burrito Deluxe, and his two solo projects (with Harris’s magnificent harmonies softening the edge), Grievous Angel and G.P. –were Trojan Horses carrying the unadulterated strains of traditional country and gospel onto our turntables, changing the vibe of our late night, stoned out listening sessions. Parsons’ tender, sentimental tales of heartbreak and desperation, abandonment, temptation, the longing for the simpler, guilt- and guile- less days of childhood and home, the cry for forgiveness, somehow clicked with us as they hadn’t until he made their case. The despair in his voice resonated somehow, stopping us in our tracks to demand a harder listen. There’s more church – sin, repentance, penance – in those ballads than anything I ever experienced on my Catholic Sunday mornings. [8] Hickory Wind. Wild Horses. In My Hour of Darkness. Sin City. How Much I’ve Lied. That’s All It Took. Still Feeling Blue. Kiss the Children. The misleadingly titled Hot Burrito #1. A Song for You. We’ll Sweep Out the Ashes in the Morning. Streets of Baltimore. Brass Buttons. Songs of flawed men (invariably men) trying to eke out a decent life in a world where the cards are stacked against them; losing their way, living recklessly, making one bad decision after another, succumbing to Satan’s temptations, trying and failing (invariably failing) to do the right thing; the pain and disappointment in his voice so visceral that we conflated it as our own. Much to our surprise, we found music from America’s heartland was as ‘heavy’ as it gets . The bowed shelves carrying our albums broadened their acceptance criteria. The Carter Family, The Louvin Brothers, The Stanleys, Willie, Waylon and the boys were as likely to be played in the late night after-parties as The Grateful Dead; the smoke hovering at the ceiling, the beer, cigarettes and joints hiding our tears and ravaging our throats while we talked of things that mattered. New waves of singer/songwriters – Townes Van Zandt [9], Jerry Jeff Walker, John Prine, Elvis Costello, Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle, Dwight Yoakam, Jason Isbell, Wilco, Chris Knight, Chris Stapleton and so many others in the decades since—listened as well, encouraged to dip their toes or dive into the deep end of pure country, gospel and R&B whenever they felt so inclined. The boundaries had been torn down.

*

Oh, my land is like a wild goose

Wanders all around, everywhere

Trembles and it shakes till every tree is loose

Roams the meadows and it rolls the nails

– “A Song for You,” Gram Parsons [10]

Born Ingram Cecil Connor III in Winter Haven, Florida, to Ingram Cecil (Coon Dog) Jr. and Avis (née Snively) Connor, he grew up in Waycross, Georgia just north of the Florida state line on the fringe of the ‘land of trembling earth’ as the Seminole People called the Okefenokee Swamp country. Both Coon Dog and (Big) Avis (especially) [11] brought significant family fortunes into their union. A friend from that time described Parsons’ childhood as one of ‘oppressive boredom’ with little direction or discipline, nothing to do and endless time and money to do it. He found refuge—and attention and girls—in music. His recklessness was exhibited at a young age. He was expelled from the military boarding school where he was sent in the fifth grade, ostensibly [12] to provide him the discipline lacking in a home that many have described as a setting for a Tennessee Williams play: Alcohol, adultery, Deep South manners, religion and tragedy. The booze flowed freely in the Connor household and at endless parties and social functions in the Cherokee Heights homes of Waycross’s elite or at the Okefenokee Country Club. Coon Dog committed suicide when Parsons was twelve. Within two years, Avis married Louisiana salesman, Bob Parsons, who fit right into the role of drinking partner and adopted Gram and his sister, (Little) Avis, and they, his surname. Big Avis died from cirrhosis of the liver on the day of Gram’s high-school graduation.

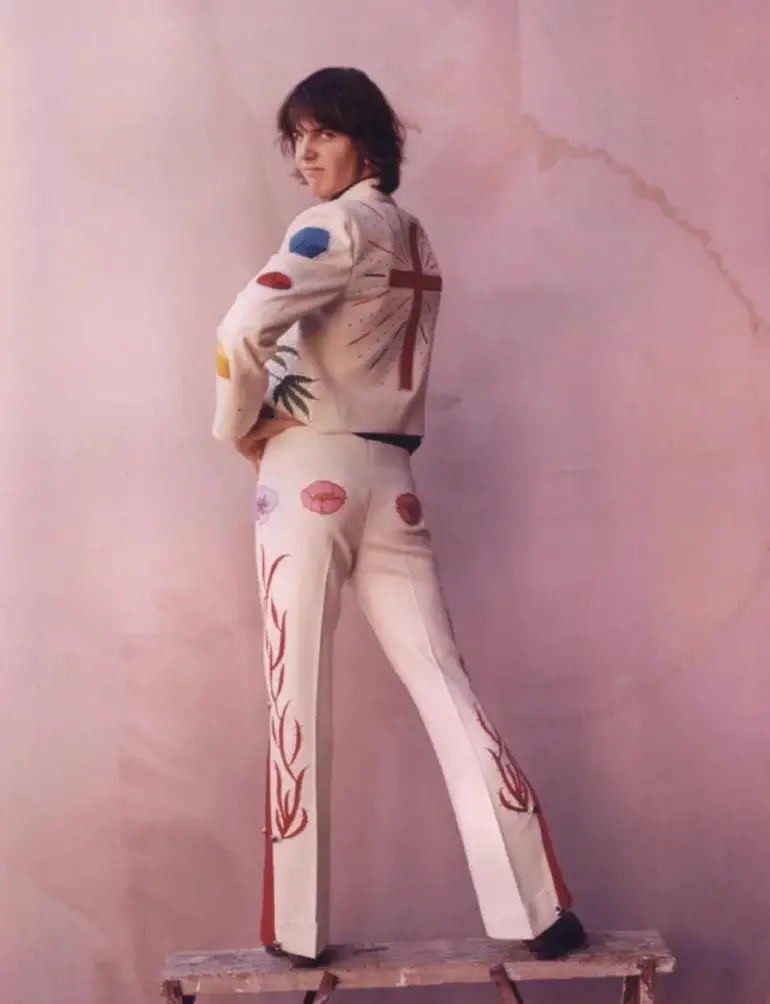

The photographic record reveals an impish, man-child complexity to him. Thin almond eyes weighed down at their outside corners, often circled in dark shadows, twinkling or dulled with a combination of innocence, joy and a weary sadness that put an asterisk against any smile that the photographers were able to coax as he gazed out from the album covers or promotional shoots. They seemed to convey, those eyes, the strain and remorse of one who knew he was a sinner, knew he would sin again, and seemed to understand—some have said ‘desire’—that his fate ended in some hell-bound conflagration at an early age. It’s hard to believe, given his family history, that he didn’t know where his excess would lead.

His sartorial tastes were a testament to his preoccupation with the holy trinity of heaven, hell, and country music. In a nod to Nashville (and Elvis) at a time when denim and flannel was the onstage uniform of choice in the West Coast music scene he inhabited, he preferred a snow-white, crease free, Nudie suit embroidered and sequined with the underworld’s flames running up his pants and colorful vines of marijuana, poppy flowers, pills, and the crude outline of a nude woman [13] spreading over his jacket and lapels. A huge crucifix dominated the jacket’s back. He’s the one a girl’s mom and dad might have chosen if asked to approve a suitor from a lineup. They would have regretted that choice, I think.

*

Such a shame

That it’s so hard for me

To tell the truth to you

– “Kiss the Children,” Ric Grech [14]

He was unreliable or evasive in interviews and discussions of his life and music. “[He] never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” Little Avis said of him. He was equally unreliable as a band member and in relationships. The Byrds booted him for his lack of commitment and the inability to show up on time and sober for rehearsals and shows. The Burritos did the same. The Rolling Stones expelled him from their Exile on Main Street sessions in the south of France for his disruptive influence. When The Stones boot you for being too excessive, what else is there to say? He cheated on the women in his life and was an absentee parent. Growing bloated and disheveled from the long bouts of excess, he was said to have become increasingly prone to angry outbursts near the end. Would he have made it as far as he did in today’s culture where the verdict on reckless, selfish, behavior comes swift and unforgiving, leaving no wiggle room to pronounce a man flawed; a man trying, and failing, to be better?

His songs didn’t lie or cheat. They had little to do with entitlement or privilege. They weren’t written or arranged to cash in on the riches from large recording contracts or filled arenas. We cringed at the pleading desperation in his voice as he hung on to a note, patient, slow, and heartfelt, simmering with emotion while recalling long ago peaceful days, real or imagined, of childhood play and friendships:

In South Carolina

There’re many tall pines

I remember the oak trees

That we used to climb

But now when I’m lonesome

I always pretend

That I’m getting the feel

Of hickory wind

– “Hickory Wind,” Gram Parsons & Bob Buchanan [15]

It would be careless or disingenuous to over-romanticize Parsons. He was selfish and spoiled, leaving a trail of pain and complicated, conflicted emotions for those left behind. It would be equally careless to ignore the torment and longing for love and attention from his broken, tragedy filled upbringing. Substance abuse and apathy are tried and true ways to keep the pain away. His music was an effective outlet for the confusion and distress that he carried inside. Though the songs stayed mostly true to standard country themes, the anguish and grief somehow resonated with more ‘sophisticated’ audiences: Lovers cling to one another on dance floors, oblivious to anything else around them; decent men, jilted at the altar or left behind in the big city lights, drink alone on their stools in the dark corners of rundown bars; guns hang on kitchen walls (we know what Chekhov said about guns in the room); friends die too young; prodigal lovers return home; a grieving son catalogues the physical remnants left behind from a mother who drank herself to death. Loss, love, desire and the need, always the desperate need, for forgiveness. Parsons’ songs fit perfectly into the ethos of despair and desire for a generation that felt betrayed and cheated in the consumer obsessed madness metastasizing across the American dream. As unlikely as we were to find ourselves in the stories he sang to us, those trees, that place, those remnants, that lonesomeness, those barstools, that gun all became ours; each song a prayer, an invocation begging God to take us back to a better time, to soothe our anguish, to wash us clean. Listening to Gram Parsons was, and is, an immersive, transcendent experience. His stories became our stories for the three or four minutes they played, lingering long after the last note faded away. He was an artist.

He is, in death, larger than when alive. Biographies, tribute albums, covers, festivals and acknowledgements from some of the top artists of our times have far surpassed the meager output and acclaim that Parsons was able to muster on his own. His worldwide admirers, this writer included, will not let his memory die. The songs and that voice are just too good, too emotionally raw and honest, to allow them to fade away. On my last visit to Joshua Tree in October of 2022, a couple from England snooped around the base of smoothed granite boulders with Cap Rock fifty or so feet above, slanted down like a Boston ‘Scally’ cap greeting us with a furtive nod. A couple from Japan joined me at the top to lean against it and take selfies. They were there for Gram, one of them told me. Down on the desert floor, others walked around, circling the rocks, pausing to talk, pointing here and there as if they were on a mission. We drank from our water bottles at a picnic table near the parking lot. Someone lit a joint. I declined. Those days are long gone for me (other than an occasional edible). The drive back down State Route 62 is too steep and curving and filled with maniacal drivers for me to chance it. We talked of the music that Gram Parsons brought into our lives and how it moved us and moves us still. We sat in the quiet of this vast, mysterious desert dolloped with mounds of eroded volcanic rock assembled in bizarre puzzle pieced Jenga-like creations. Joshua Tree’s eponymous yuccas surrounded us, pushing their arms up into the sky like a congregation at a Pentecostal service. We smiled at the notion that some songs recorded a half-century ago by such a young man could bring a disparate group like us to this place. The woman from England sang out in a sweet, pleasant voice, ‘twenty thousand roads, we went down, down, down, and they all bring us straight back here to you.’

Gram Parsons is dead fifty years.

Damn.

— —

Joe McAvoy’s essays, short fiction, music and sport pieces, satire and poetry have appeared in publications worldwide including Catamaran, The Sport Digest, The Opiate, Timberline Review, Speculative Grammarian and many others. He lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, Kyle, and their English Lab, Rosie.

— — — —

[1] That exclusive (and infamous) club whose membership includes Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Mama Cass and others (Amy Winehouse the last to join, as of this writing) who died at the age of twenty-seven from hard living at the height of their artistic careers.

[2] All quotes and most biographical information from either Ben Fong-Torres’ Hickory Wind, Extradition Publishing, 1991; Bob Kealing’s Calling Me Home: Gram Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock, University Press of Florida, 2012 or David N. Meyer’s TWENTY THOUSAND ROADS: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music, Villard Books, 2008. If you can only read one, read Meyer’s.

[3] Lyrics from ‘The Road’, one of a few Emmy Lou Harris’s tributes to him. From her album, Hard Bargain. Nonesuch Records, 2011.

[4] The official narrative is that theirs was not a romantic relationship. There were hints otherwise. Who cares? They were magic together.

[5] They’re still in place today though significantly diluted.

[6] It would be a sin of drastic proportions to not mention Chris Hillman’s contributions. He was a master instrumentalist and significant collaborator in the songwriting process. He didn’t have Parsons’ voice and instinct for those high lonesome songs.

[7] He even overdubbed a ‘fake’ live audience and the sound of breaking glass over a medley of Cash on the Barrel Head and Hickory Wind on the Grievous Angel album.

[8] Though little in the way of absolution.

[9] Ah, Townes. This is arguable. He was as much a seminal influence as Parsons, deserving of his own elegies.

[10] ‘A Song for You’, from the album, GP, 1973, Reprise Records.

[11] The Snively Family of Winter Haven, Florida, was Florida’s major citrus growing landowner/fruit processor/wholesaler.

[12] There were some, including the school’s academic dean at the time, who have said that he was sent away because parenting was a distraction to Avis and Coon Dog’s lifestyle.

[13] The same woman who is seen flying across the cover of Neil Young’s Zuma album. Coincidence?

[14] ‘Kiss the Children’, from the album, GP, 1973, Reprise records. Written by Ric Grech. Oh, those cowboy harmonies.

[15] ‘Hickory Wind’, by Gram Parsons and Bob Buchanan, first recorded on The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo album, Columbia Records, 1968. I prefer the live version with Emmy Lou Harris on Grievous Angel, Reprise Records, 1973.

:: Stream Gram Parsons ::