Punk legend John Doe works for the first time as the John Doe Folk Trio to create a haunting concept record set in a pre-industrial American West.

Stream: ‘Fables In a Foreign Land’ – John Doe

John Doe doesn’t write fables.

At least, not “what fables are supposed to be.” Those, he says, have morals. A compass. When they’re finished, you know what direction you’re supposed to be heading. Though Doe’s new record is entitled Fables In a Foreign Land (out May 20, 2022 via Fat Possum), the use of the word “fables” is almost tongue-in-cheek. The record is a historical imagination; taking place in the 1890s, these songs are sung by a wanderer, a stranger who collects histories and sings them into the open air. Recorded live in one room, Fables In a Foreign Land has a campfire and dirt road quality – these songs crackle like sparks toward a dark sky and burn under a midday sun. The record functions as an anthology of hurts and triumphs in a wide and lonely land.

Working for the first time in a trio with drummer Conrad Choucroun and bassist Kevin Smith (as well as co-writes from longtime collaborators and friends Exene Cervenka, Garbage, and Louie Perez of Los Lobos), Doe has created what he calls “his version of folk music.” But as a denizen of LA’s early punk scene co-fronting the legendary band X, Doe is not a stranger to telling stories with his music.

The songs in X’s discography are visceral and evocative, peopled with richly detailed characters. Doe’s solo records also offer similar musical landscapes, and this is where folk and country intersect with punk rock for Doe: a tangible time and place, the visual summoned by sound and lyric. Doe’s long history as a poet also finds its way into Fables. A poem accompanies the record, tying its storylines together:

In the dusty world of Fables In a Foreign Land, our nameless narrator shares the stories they hear on their travels, mostly without passing judgment.

They are stories driven by observation or hearsay, brief connections and joys, destructions large and small. Though meant to take place more than a hundred years prior, Doe hoped that in the isolated vastness of the COVID-19 pandemic, his Fables might speak to people separated by long and treacherous roads. The map may not be complete, but there are miles of open country under a wide and inviting sky.

— —

:: stream/purchase Fables In a Foreign Land here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH JOHN DOE

Atwood Magazine: I think when you’re mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind for people is punk, but you’ve always been involved in country and folk in some way, since The Knitters etc. Where do these genres intersect with punk for you?

John Doe: Creativity is creativity, and force and drive and ambition and all those things are mixed up together. But musically, lyrically, I think [punk and folk are] very similar in the stories being told, or the lessons. Folk music, country music, and even good rock songs always have, to me, a time and a place and you can [visualize] something. I don’t get classic rock and stuff where there is no more detail than, “Do you feel the way I feel?” No, I don’t. I couldn’t possibly feel the way you feel, Peter Frampton [laughs].

The press release says this isn’t a concept album. Do you consider this a concept album?

John Doe: Well, I think I was trying to be evasive, because when you say “concept record,” you immediately think “pretentious.” These songs started developing in a certain way and I thought, okay, let’s see if I can stay on track. Let’s see if we can remain in a certain world. I tried to create that world so that a listener could lose themselves in that for a little while. Not that it’s all just entertainment or fantasy, because there are some difficult subjects and difficult situations. So yes, it is [a concept album]. It’s necessary to cop to what’s obvious.

I’m really interested in what you said in the press release about not being sure if these songs contain mythology; what, to you, is mythology? What defines it?

John Doe: Mythology, to me, is like a fable in that it’s a story that’s told over and over. There’s a mythology of people, a mythology of punk rock, there’s the mythology of growing up and experiencing things that become eras and are newsworthy, whether it’s integration or certain eras of protests or things like that. Then of course, there is classic mythology. Here in the U.S., it’s a little scattered, because you’ve got Greek, Roman, Norse, etc. But I think by saying this doesn’t have a moral, I was addressing what fables are supposed to be. Sometimes fables have a moral. These [songs] don’t really, except maybe that there is spirituality, but there may not be a god, at least not the way that people think of it in certain religions. Here, good is not necessarily rewarded, and struggle is inevitable, but you have to try to move forward.

How does spirituality guide the record? You’ve said you’re not necessarily religious, but are spiritual. I know you’re a poet, and for me, poetry has been more spiritual than any religious text I’ve read.

John Doe: Poetry is a good example, because where does it come from? I’m not gonna say it comes from Jesus Christ, my personal savior [laughs], but it does come from somewhere. And it’s also a function of age; as you get older you see things that may appear coincidental, but they’re not. Things happen, not necessarily for a reason, but they’re connected in some mysterious way and that mystery of life, love—I love the fact that I don’t understand. There are plenty of things that I don’t understand that I’m happy to leave mysterious. So the spiritual elements of this album are a part of telling the story. There’s a narrator, and this person’s on a journey and they’re wondering, “Why me? Why have you forsaken me, Lord?” because that’s what they were brought up with, a traditional kind of vengeful god or a god that rewards good. In the song, “See the Almighty,” they’re questioning that and can see evidence of a great spirit, just because it’s so damn hard to get through this valley.

It’s interesting what you said about the U.S. and mythology, because I feel like the American West is one of the most salient American myths. I’m curious about why you wrote about this era of the late 1800s and whether or not you feel it has any connection to now.

John Doe: It does have a connection to now. I’d say one of the first songs that started me on this path was the song “Missouri.” We were touring, I think in 2017 or 2018, and we drove from Kansas City to Omaha and back, and the Missouri River had flooded. Tens of thousands of acres were under a couple feet of water, but I hadn’t even heard about it in the news. That was a startling image, and I expanded on that. I think I was attracted to the era because I don’t think what we’ve gained through technology is really worth it. I’m not sure what the cost is. Having a direct connection to a problem and a solution when you’re out in nature and are experiencing something is better than whatever you can experience virtually, even though you see some incredible events or people doing wonderful things. Or stupid things. That is the soup that began it, and then as lockdown happened, I realized that with the isolation and loneliness, there were a lot of similarities between then and now. That was a fortunate realization, because I thought, “Well, maybe people can relate to this on a personal level because of what they’ve gone through.”

Your record kind of reminds me of Jim Jarmusch’s Western film Dead Man in how vast it feels.

John Doe: The vastness was intentional. We recorded it with a lot of space, and Kevin Smith, Conrad Choucroun, and I created the sound because we were just singing and playing out into the air. I didn’t want to have a lead instrument. I can manage on a guitar to serve the song, and so the melody and interplay was left to the bass and drums with a little guitar on the side. Part of the inspiration was Bob Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding,” in addition to a bunch of older records where you can hear the space. A lot of times in modern records, every space is filled.. If you go back a little bit further into older music, it was just like, good enough just to tell the story and let your mind fill in the blanks.

I’m curious how writing poetry and writing music intersect for you? Are those two sides of your creative self distinct?

John Doe: Lyrics should be poetry, but all poetry isn’t lyrics. It just depends on the rhythm or meter or if that if there’s an implied beat to it. But a big similarity between lyrics and poetry is the economy of it. On this record, there’s a lot of space, so the lyrics are purposely minimal.

Are there writers that sort of sit on your shoulder as you’re writing, or who guide you in interesting ways?

John Doe: When I started getting serious about learning poetry, I had a great teacher. But she said, “Don’t read anything that’s old. Only read things that are new. For someone who’s in their early 20s to read classic poetry, it just doesn’t relate because the language is all very different. People who were well-known at that point were Diane Wakoski and Anne Waldman, and the Beats still had a lot of sway and Galway Kinnell—he was maybe my first introduction to things being nature-driven. I’d say William Carlos Williams was always a big influence on me, with the every-dayness of his images. And of course, e.e. cummings. But I don’t know, it’s also a strange brew of Hank Williams or Skip James or Tammy Wynette or the Carter family, and then The Velvet Underground and The Doors.

I’d also say that I just listen to [my] own mind and see what comes out. I studied poetry and was interested in that, but it all comes from a different place [for different people]. Exene [Cervenka] didn’t study poetry, and she has an incredible skill where she just hears stuff and writes it down. She’s probably taught me more than anybody else about writing. She has a great sense of wordplay.

You said the album starts the way it does for a reason. Can you talk about the narrative arc of this album and also its ending?

John Doe: When Kevin, Conrad, and I were working on stuff in 2020, we had a few new songs and we all thought, “Oh, we’re working towards something at this point. We’re not just getting together to try to believe that we still have a career in music, because we’re not touring or playing live.” Then I wrote “Never Coming Back” and thought, “This is the beginning of a journey.” The image first came from the lyric, “...with a mask upon your face,” which was written in 2018, way before everybody wore masks.

The middle part is what the traveler sees, is told, or experiences. Maybe they experienced going into town and seeing someone beat a person. Maybe our narrator did see that. The narrator definitely was not the cowboy who got swept up in the hot air balloon, but they’re definitely the person who’s experiencing the song “See the Almighty” or “Down South.”

Are they also the “Guilty Bystander”?

John Doe: Hard to say. Maybe they are; maybe they heard somebody tell a story about it. The last song was written last of these songs, and if it was influenced by any song, it was influenced by “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” which is an interesting song because the person can dream up anything but all they dream are hobo dreams. I think that’s beautiful and mystifying. It offered a certain amount of hope for finding a destination. In my mind, this narrator goes across the country and ends up at the Pacific Ocean and sees this limitless, wonderful country, whether it’s in Oregon or California or wherever, and they think, “Maybe I could live here. It doesn’t snow that much, and it’s a gentle country.”

It’s almost like rather than just narrating their own story, the narrator plays more of the role of a collector of histories.

John Doe: Yeah. I also want to say that “Guilty Bystander” was a direct result of George Floyd being murdered.

John Doe: Yeah, it’s part of the air we breathe, the water we drink. Maybe the most destructive part of modern times is the 24-hour news cycle. I mean on the record, the song “After the Fall” is about the destruction of a country. John Doe: Yes. “What’s important to you?” That’s another thing that’s relevant in both time periods and maybe became more obvious in lockdown. You know, who are your good friends, and who don’t you really care about that much? [laughs] — — — — — —

Your music throughout your career has often been pretty intertwined with political events. Even though this record is historical in its setting, I assumed there were lots of direct parallels.

This record is about a lot of things. Like you said, it doesn’t necessarily have a single moral. It’s not necessarily a fable. But do you think it asks a central question of its listener?

Connect to John Doe on

Facebook, Twitter, InstagramDiscover new music on Atwood Magazine

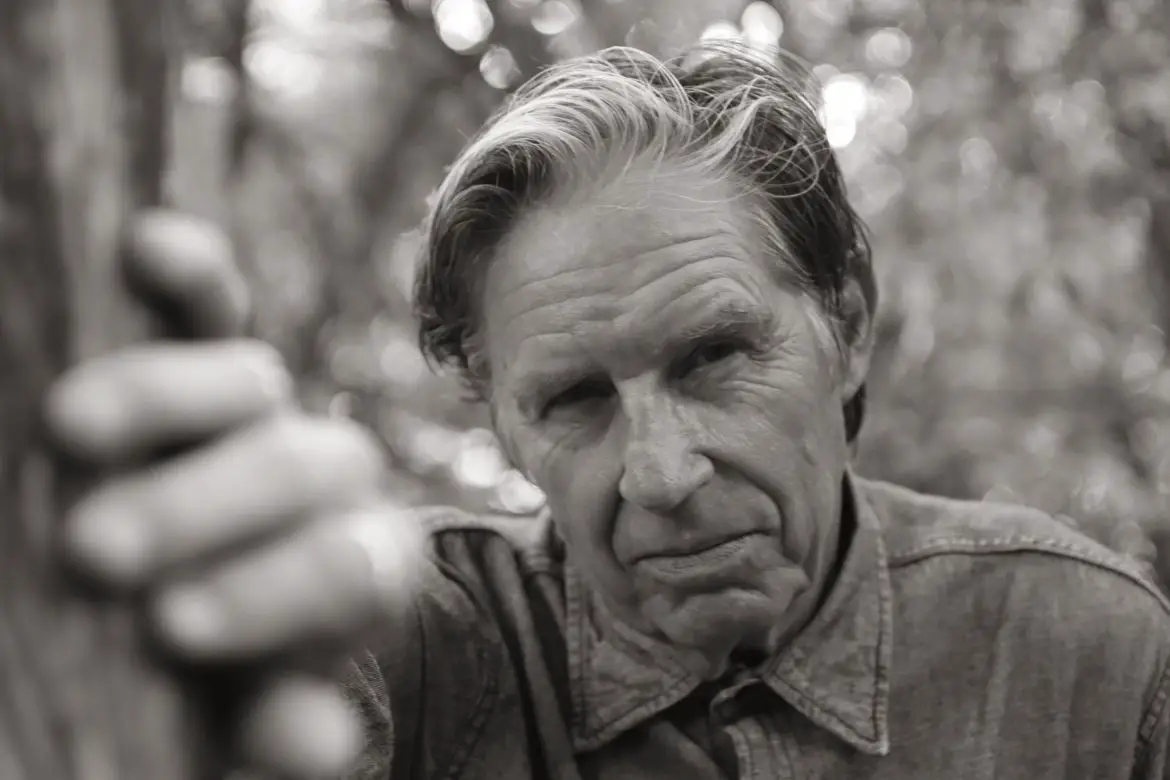

? © Todd V. Wolfson

:: Stream John Doe ::