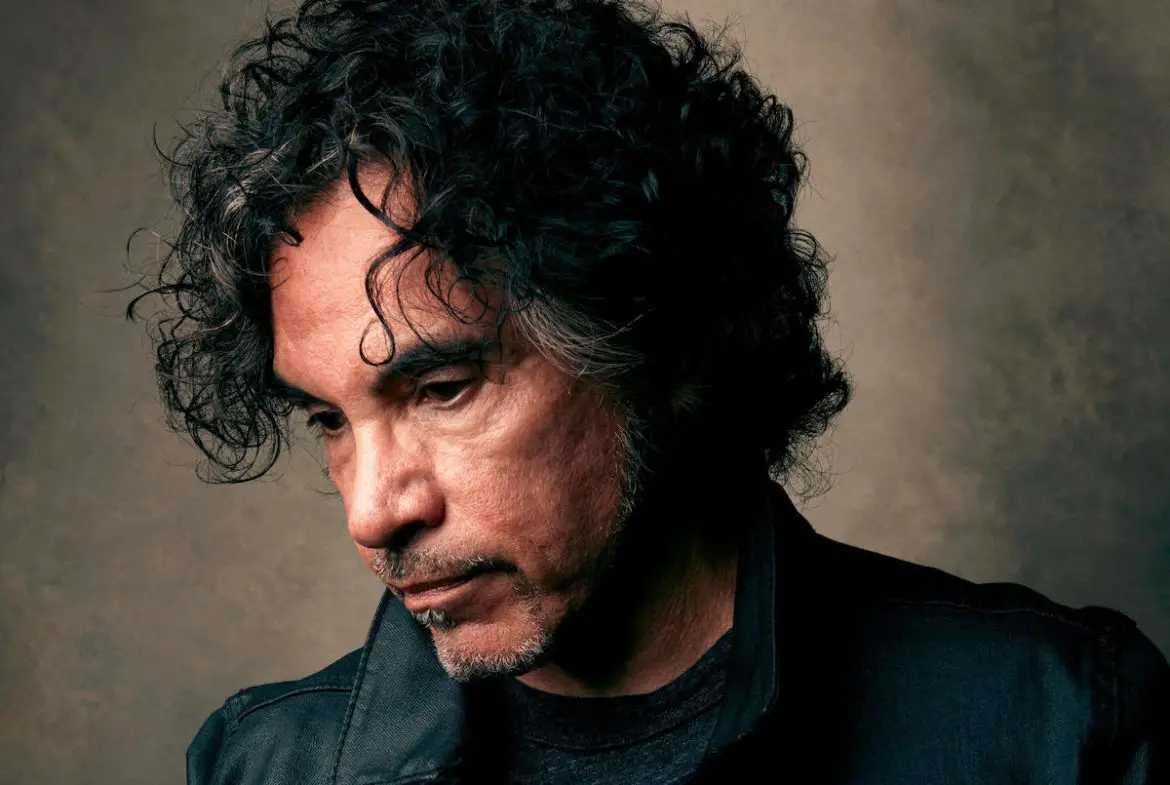

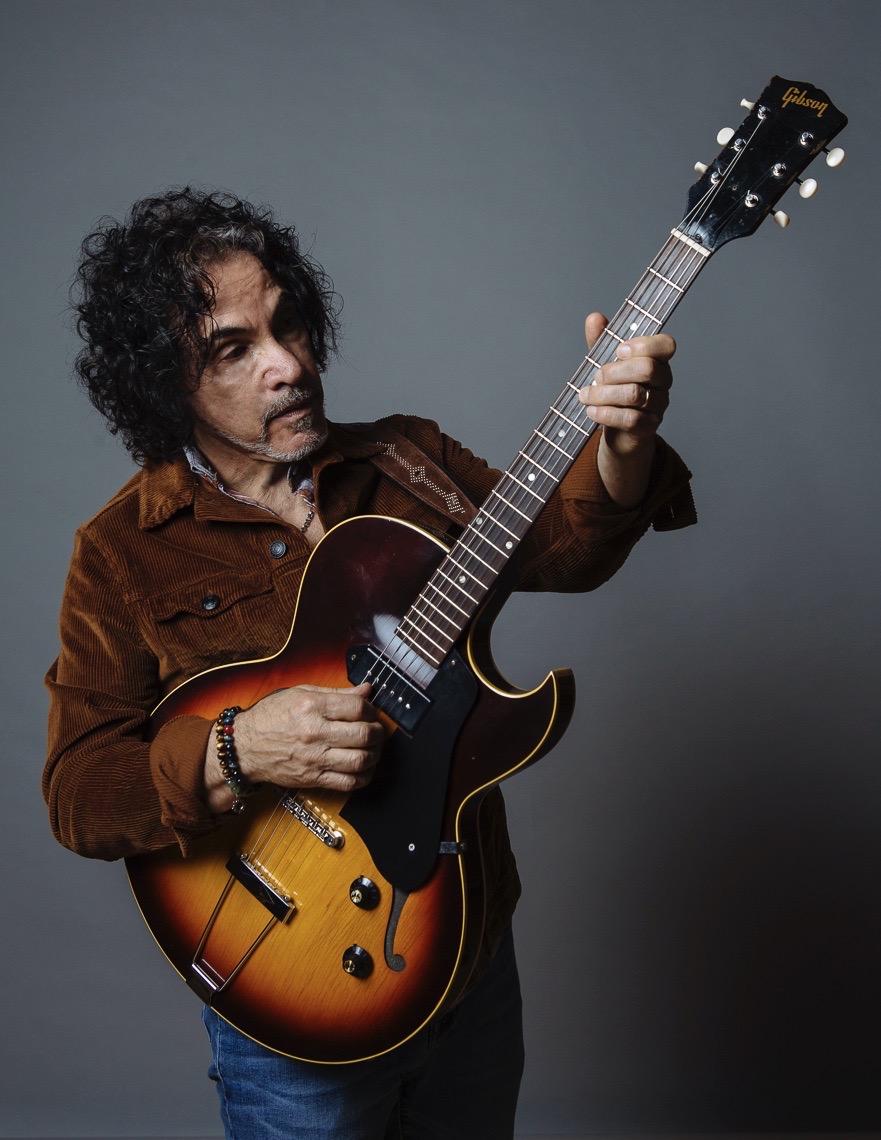

Hall & Oates’ John Oates has always had an air of mystery about himself; we discuss his rework of “Pushing a Rock Uphill,” men’s mental health, and bringing back that iconic mustache for Movember.

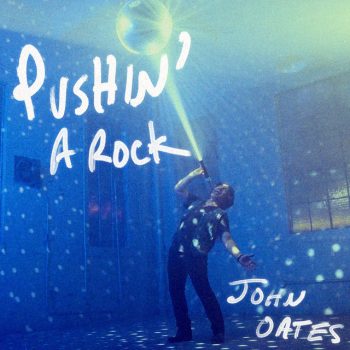

Stream: “Pushin’ a Rock” – John Oates

There’s always been an air of mystery around John Oates.

Not because he’s deliberately made himself a mystery or something. Just because if I showed any random passerby a Hall & Oates music video, they would likely perceive John Oates as the quiet one. On first impression, he’s that sultry instrumentalist who lets his music and his mustache do the talking (more on the mustache later).

However, that would be too easy a mischaracterization.

It’s not like he never sang, either. His baritone timbre added a counterbalance to Daryl Hall’s own second tenor. You might recognize it on hits like “She’s Gone” and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling.”

Yet the pieces where Oates sang lead vocals by himself never charted very high. They’re the deep cuts – the ones you don’t think about from albums that might have never crossed your mind.

Forgotten Oates tunes include: “Had I Known You Better Then” from Abandoned Luncheonette; “Alone Too Long,” from Daryl Hall and John Oates; “Crazy Eyes” and “Back Together Again” from Bigger Than Both Of Us; “How Does It Feel To Be Back” from Voices; “Italian Girls” from H2O.

And that’s just the basics. But if you’ve paid attention to the latter-day careers of Hall & Oates, you would notice a slight role reversal.

With each episode of Live From Daryl’s House, the frontman became a supporting instrumentalist, highlighting his guests and providing a template for what is consistently a good time. The mischaracterized instrumentalist, meanwhile, went back to Nashville to rediscover his roots, to rediscover the artist before the icons.

In doing so he recorded a bevy of records that explore every niche of his musicality. 1000 Miles of Life leaned in to folk, Mississippi Mile carved out a space in rhythm and blues and Arkansas dove into all things blues, bluegrass and ragtime. Not to bluster about it, but Oates’ recent discography serves to dispel any remaining mystery there might still be.

But during COVID, Oates explained, he began diversifying away from the 1920s and ’30s blues-and-roots sonic pallet with music that dabbles in more modern recording techniques and ideals.

“Pushin’ a Rock,” his latest record to follow these impulses, is actually a rework of a song he made with Nathan Paul Chapman (of Taylor Swift fame, among others) called “Pushing a Rock Uphill.”

Talking with Oates about this song was to uncover just how iterative the process of making music can be. Oates himself decided that the original just didn’t live up to its inspiration from Sisyphean myth and personal obstacle. Now, it’s not new ground to make this comparison, but I’ve never heard someone set it to the groove of a new-school ’70s soft rock ballad.

Yet somehow, that makes total sense.

— —

:: stream/purchase John Oates here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH JOHN OATES

Atwood Magazine: I always like to start with just a simple question of what have you been listening to recently? What's been on your musical plate?

John Oates: I’ve actually been listening to myself. Reason being is I’ve been making all this new music, and I’ve been doing a lot of writing and recording and teeing up all this new music that I’ve been making. So it’s more like work listening, making sure the mixes are right. Listen to the masters make sure they’re there, right. I’ve been a professional musician for so long, that a lot of my listening—and I don’t want to diminish it by saying this—but it’s more like analytical mixing. I’m listening to listen, I’m not listening to have the music wash over me and put me to sleep.

How does it feel to release new music this far into your career? Has the feeling changed, or does that stay the same?

John Oates: It’s really an ongoing thing for me. In the mid 2000s, I dove into the Americana scene in Nashville. And it kind of brought me back to the type of music that I was performing and doing way before I met Daryl. And in doing so I made what I consider to be some really good roots and blues-type records. During COVID, I began to get back into more and more modern recordings technique making tracks on my home in my home studio with using samples, using unusual sounds. In a way it gave me a chance to say “hey, you know what, I think I’ve tapped Americana. I want to tap back into my pop sensibility.”

Your new song “Pushing a Rock” reminds me of the early hits like “Sara Smile” and “She's Gone.”

John Oates: It’s definitely closer to the 70s than the 80s, I agree with you. I liked the 70s a lot better and I’ll tell you why: the 80s were just this intense roller coaster of pop stardom and pop fame and really a lot of demands on time and, you know, just a crazy rocket ship ride. Whereas during the 70s everything was new. Every city I went to was new.

I talked about this when I wrote my autobiography: I think the story of becoming is much more interesting than the story of the victory lap. Because that’s when you’re formed, you’re formed when you have the opportunity to experience things for the first time.

Speaking of new things: watching the video for “Pushing a Rock” and seeing you fill the singer’s role. It just feels like the subversion of what I would normally expect. How does it feel to fill that role, how is it different from being the “instrumentalist” of the duo?

John Oates: Well, I’m not the instrumentalist, here. I’m a songwriter, I’m a singer, and producer and all those things. Obviously, when someone is singing a song, they’re going to be the focal point of a visual medium.

What I wanted to convey in that video was overcoming obstacles. It was about tapping into the concept everyone, regardless of who they are, what their station in life is, they’re going to have to overcome something in their life. That’s important and, perhaps, very daunting to accept.

It does invoke a Sisyphean kind of imagery.

John Oates: That’s where I got the idea, is from the Greek myth, without sounding too academic. This song is actually an evolution of a prior version of the same song. I recorded a song called “Pushing a Rock Uphill…” on an album I did back in 2015, called a Good Road to Follow. And one of the collaborators was Nathan Paul Chapman, who was Taylor Swift’s original producer for the early part of her career.

I had read somewhere that Taylor had gone on to work with other producers and… I had a gut feeling and I called him up and he said “I’m in a new place creatively. I don’t know exactly what my next steps gonna be.” And I said, “Well, I don’t know what my next steps going to be either. Maybe we should write a song about it?”

So I went over to his house, actually into the same little studio where he did all the Taylor stuff and we joked about that a little bit. I said, “Hey, man, is that the microphone Taylor used?”

But at the same time, I told him this idea about the Sisyphus myth, pushing a rock uphill and how we all have to overcome whatever it is that we’re facing. And he loved the idea. So we wrote it together. And then I recorded it.

However, I didn’t feel the music held up to the to the to the power of the lyrics and I never felt comfortable with it. During COVID I revisited the song again and I went, “you know what, I can do better. I can take this lyrical idea and I can turn it into something better.”

So that’s what I did. I rearranged it, I changed the chords, I changed the groove completely. Then I got a hold of Nathan. He said to me, after he heard it, “this is what the song always should have sounded like.”

And that made me feel really, really good.

Do you prefer jamming things out? Or do you prefer the iterative form of working towards perfection?

John Oates: Well, I do like to work toward perfection. I’m a little bit OCD when it comes to that, but I don’t discount the natural. I love the idea of spontaneity and jamming and letting things happen. But I have my own workflow. And the workflow always starts with an initial inspiration of some sort, then it gets down to the craftsmanship of that inspiration.

Years ago I was talking to Vince Gill about recording here in Nashville and he said “when you’re producing in Nashville, you’re like the director of a film. It’s not about who’s the best guitar player, there’s 100 best guitar players, there’s 100 best drummers, you have to pick the exact right person for the moment for that emotion, or that sound that you’re looking for.”

And I never forgot that.

•• ••

Being a creative is to battle with your own self.

To know when to let yourself go on that tangent, or to cut it back and keep yourself attached to the original piece.

It’s no secret that being a creative also comes with a certain struggle with mental health. I don’t even statistics to prove this; history is littered with stories of writers, musicians and artists who battled their demons ending in victory or untimely demise.

Oftentimes during my own bouts with anxiety and depression, I lean back on the discography of 70s music for help. Records like James Taylor’s Greatest Hits or Carole King’s Tapestry are the go-tos. But so too does Hall & Oates’ Abandoned Luncheonette fit in this category.

These songs work like a mental and spiritual balm, calming the mind’s eye and piecing it back together from shambles. Hell, you could place “Pushin’ a Rock” on any of those Hall & Oates records from ‘73 to ‘79 and it would fit, no problem.

Mental health issues also aren’t just limited to younger generations, of course. But Oates recognizes that in both arts and sports, it’s the whipper-snappers that are making the effort to discuss these topics and find the people they need to relieve the pressures of being human.

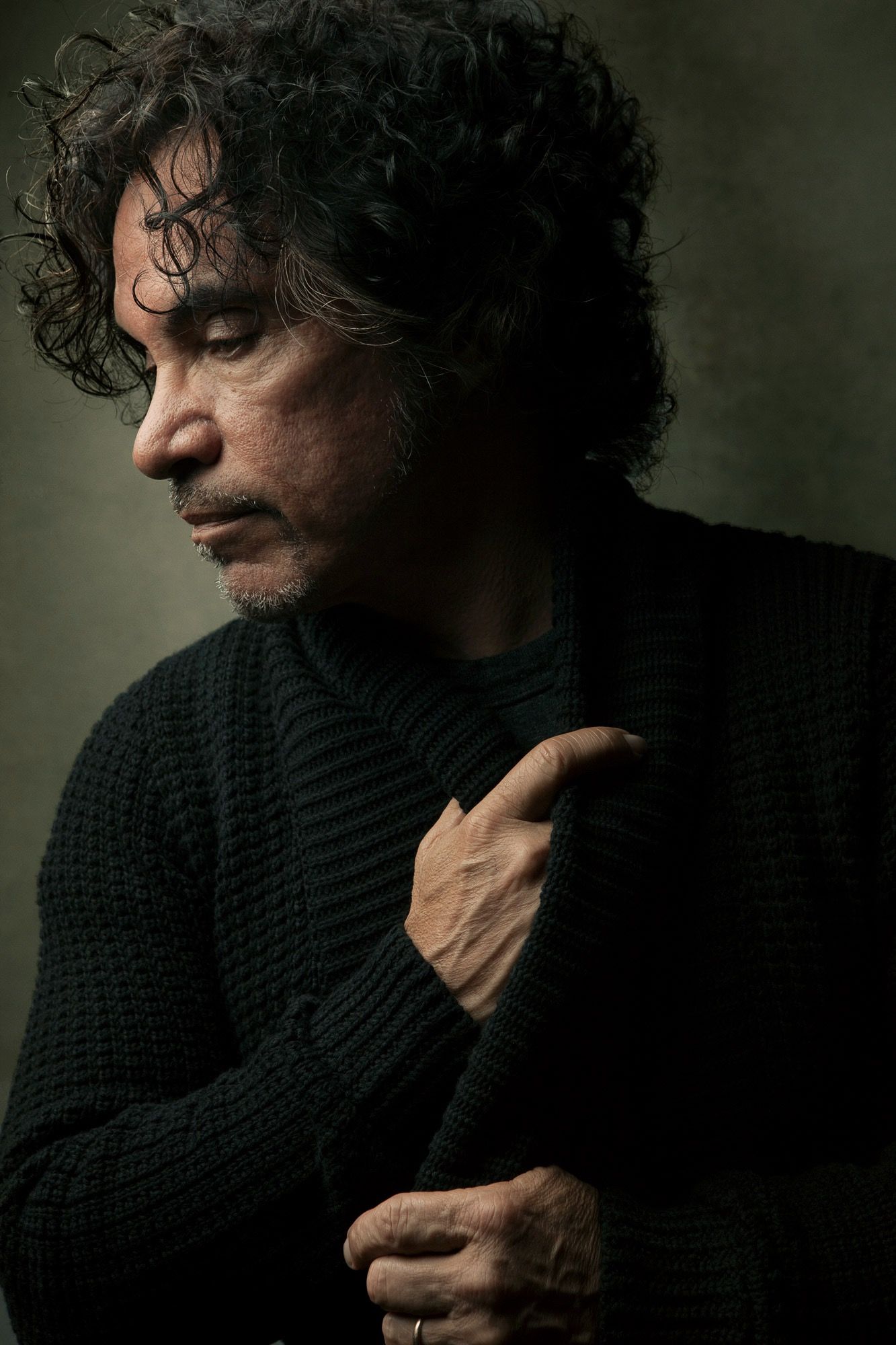

Recently, Oates has teamed up with Movember to bring back that classic ‘stache from days of yore as an ambassador.

Most people might recognize the organization for its efforts in curing prostate cancer. But they also work for improving mental health resources to prevent suicide.

Oates says he originally shaved the mustache after his own rollercoaster ride through popular stardom in an attempt to showcase his own evolution. But when the Movember organization reached out over social media, he answered with a resounding yes. He aims not to proselytize, but to help shine a light on the simple fact that is okay to ask for help.

And perhaps there’s no ambassador better served to discuss the ups-and-downs of life. In the years after the ’80s, Hall & Oates were deemed “yacht rock” and considered to be flimsy music among critical circles. Derided as music for jet-setters and the poshest of listeners.

But the last 15 years have dispelled that notion, too.

Hall & Oates have probably never been more successful than now, and it’s thanks to us kids. Yes, us same kids that are fighting the good fight for mental health. It might have been ironic at first, it might have come from a general curiosity. But that quickly changed: from youth a new crop of fans has formed.

And so the duo have experienced a true career resurgence from artists like The xx sampling “I Can’t Go For That,” to Anderson .Paak namedropping them on “Heart Don’t Stand a Chance,” to just the general fact that The Very Best of Hall & Oates is one of the best selling greatest hit records of the last decade.

Without a doubt, it’s never been a better time to be Daryl Hall or John Oates.

And Oates, as the self-proclaimed Patron Saint of Facial Hair, is not missing his chance to do something positive with that platform.

Atwood Magazine: You mentioned how you get a little OCD when you're in your creative space. And that kind of segues into how you're bringing back your iconic mustache for Movember as an ambassador for Men’s Health Month. So my question has two parts: how did that partnership form and how does mental health play with the creative space?

John Oates: I believe they have a brand ambassador every year and they reached out through through my social media people and I thought it was the right time for me.

It’s funny, I have a very complicated relationship with my facial hair. I felt as the 80s were ending, I was changing as a person. I felt like the mustache in a way represented that old guy that I was trying to move on from, so I shaved it. And throughout the 90s, even into the early 2000s, I didn’t have any mustache. And in a way, I wanted to make my own personal statement, not that I was no longer that guy, but I’ve evolved as a person.

Segueing into the second part of your question: it’s an important movement, it’s an important initiative. Men, I think in general, tend to hide their feelings, tend to not want to address certain things, especially medically, or emotionally or mentally.

And I think it’s definitely changed. I see it in the world of entertainment, I see in the world of sports, how the younger generation is much more open about their issues and their mental fitness. They’re more sensitive to it, and they’re not afraid to talk about it, which I think is really healthy.

And here, again, the synchronicity with “Pushing a Rock Uphill, it’s the exact same thing. Everyone has their struggles, and everyone has their issues. I don’t like to proselytize, that’s bullshit. I don’t care about that. But what I do care about is shining a light on the possibility that people, men in particular, should not be afraid to seek help and to look for ways of dealing with things that can be debilitating. That’s why I wanted to jump on board with this.

Just to bring it back down small: The self-proclamation as the Patron Saint of Male Facial Hair —

John Oates🙁laughs) I did call myself that, I believe.

I also don't think any artists like you and Daryl have had quite the critical resurrection or resurgence. In the past 20 years your music has gone from punch line to respectable to outright influential. From the inside looking out, what do you think changed over those years?

John Oates: There’s a number of factors. We are of the generation of the old established music paradigm of the big record label with their henchmen terrestrial radio, with the other henchmen of brick-and-mortar record sales. It was all a cadre of a system. It worked without a doubt; you signed to a big label, the label promotes you on radio, you have a hit record, the record sells the album, and people go buy the record, and everything was hunky dory.

Now, all of the sudden, people had the whole digital world and virtual world to discover music, and no one telling them what they should listen to what they should like, what’s good, what’s bad. And the younger generation brought about this change (which was the greatest thing that’s ever happened to music) to give people a completely open palette and opportunity to discover, to make their own decisions to share with their friends.

And I noticed it immediately when we were doing shows. Our audience became younger and… there was this weird kind of ironic thing. They were coming to see if we were a throwback, nostalgic group. And then they realized that we weren’t in a throwback nostalgia group! We were actually good, we played with energy and vitality, and we had an amazing band. And the songs were really good. So instead of the audience having this ironic expectation, it turned into actual fandom and a bigger appreciation.

Then then younger bands began to talk about us as being influential to their fan base and on social media, and their fanbases began to spread the word about us. So it was a very organic kind of build.

Speaking of, the official Hall & Oates Instagram was sharing songs that sample or otherwise were inspired to use parts of the Hall & Oates discography. Are there any recent pieces of music that mentioned or sample your work that you really enjoy?

John Oates: We get asked about licenses a number of times a week. Some of them are better than others. As long as they’re not objectionable, we usually approve them. I actually go back to the very first one that I that I was aware of. Now, I might be wrong, maybe there were others. There was a group called De La Soul that took “I Can’t Go For That” and they called it “Say No Go.”

I remember we were doing a music video in a park in New York City. During a break in the shooting this girl came up to the front of the stage with a cassette and handed it to me and said, “Have you heard this?” And I said, “No.” It was a regular little cassette. And De La Soul was handwritten on the cassette and I put it on. And I was like, “Whoa, wait a minute, they’re taking our song and making another song?” I didn’t really understand the whole concept. And then of course, it became pretty clear what was beginning to happen.

So I always go back to that first one, because it really opened my eyes to the possibility that a whole new world was about to happen.

— —

:: stream/purchase John Oates here ::

Stream: “Pushin’ a Rock” – John Oates

— — — —

Connect to John Oates on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Sean Hagwell

:: Stream John Oates ::