I talked with Ambrose Kenny-Smith for The Murlocs’ ‘Rapscallion.’ Then I had a nervous breakdown. In the time since, they released another record, Calm Ya Farm. Seven months in the making, consider this a review of a band’s evolution, its tragedies and its successes.

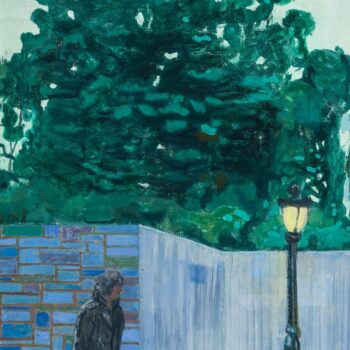

Stream: ‘Rapscallion’ – The Murlocs

As I get older, I start to realize that I’ve always known that I’m just more of a wordsmith or lyricist, and performer, first and foremost, rather than like a musician. And that’s always been my strong point.

– Ambrose Kenny-Smith, The Murlocs

Ambrose Kenny-Smith is maturing. And he doesn’t like it.

Ask him about the difference between his dog days of youth and his present form and he laments, “I was pretty, pretty gross. And I loved it. Whereas these days, just like a bit too clean cut.”

The once teenage heartthrob of King Gizzard and the Lizard is now in his fourth decade, with a multitude of albums and uncountable concerts behind him. He sports a clean black matte mop of hair and shaven face, cheeky mustache not withstanding, and there’s nary a pimple or zit screaming through the Zoom call.

His focus was now set on The Murlocs’ then-latest record, Rapscallion, and youth was his totem; “I grew up as a passionate skateboarder so I was always out the door, getting on buses, or hitchhiking or getting trains so there’s sort of elements and parts of songs throughout the album that are true in some ways; I did experience these sorts of scenarios.”

The album he’s talking about is Rapscallion.

Raised by wolves in a modern world I was sheltered never heard

Dreams shut down by my mum and dad, conceived in a caravan

I’ve been living.

I’ve been living, I’ve been living under a rock.

– “Living Under a Rock,” The Murlocs

Released from ATO and composed in pandemic-induced isolation by The Murlocs’ Callum Shortal, Rapscallion reflects a sea change record for a band that is often categorized as peripheral to Kenny-Smith and Cook Craig’s contributions to King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. But make no mistake: there’s nothing peripheral about this record.

“Cal wrote all the music for Rapscallion. So he was sending me tracks very quickly,” Kenny-Smith tells, “showing his true potential of songwriting and his creativity.”

With Kenny-Smith’s duties split between multiple projects, lead guitarist Cal Shortal remained wholly focused on the project affectionately called Uncle Murl.

It’s a simple dynamic on the outside: Shortal composes the music, Kenny-Smith pens the words. From there, multi-instrumentalist Cook Craig, keyboardist Tim Karmouche and drummer Matt Blach fill in the gaps. In the case of Rapscallion, the oeuvre stems stems from a surge of creativity Shortal experienced during COVID lockdown.

Such alliance is archetypal to the genre; Jagger and Richards, Plant and Page or legendary countrymen Bon Scott and Angus Young. The history of rock n’ roll is punctuated by the partnership between the frontmen and guitarists. And the creativity only beget creativity.

“It really helped me easily find the inspiration and influence to start writing this whole storyline,” Smith says, using afternoons and evenings to write the majority of the lyrics.

The lyricism was not without problem, however. As Shortal experienced a surge of creativity during the lockdown, Kenny-Smith, ever the rambunctious bundle of energy in life as he is on-stage, found the doldrums of isolation no good for writing.

“I knew no one wanted to hear about me struggling to find toilet paper at the supermarket or go for a walk around the street before curfew,” he explains, “So I just had to channel that vibe and it got me excited and invested into it.”

Thus he shifted away from the introspective, experiential and self-referential efforts of yesteryears—think Bittersweet Demons or Manic Candid Episode — and towards a story concept. What resulted was a twelve-track garage blues epic soundtracking the escapades of the eponymous Rapscallion and his journey from the Australian bush to the city. An act of revolution to the ancien regime.

It’s the type of album made for a movie yet to be made but with plenty of Hollywood references, from Rebel Without a Cause to The Outsiders. In context of an Australia, however it evokes the bushranger or swagman of national folklore.

Kenny-Smith assures that it’s not intentional, that “there’s definitely a fair amount of, like, Australiana influences,” he said in our October phone call, “but it’s sort of just like, a natural thing to go off without realizing if it’s ‘Australian’ or not.”

Still, you’re probably wondering what the hell a bushranger or swagman is.

Shopkeeper’s running a tight ship

Went ballistic in the pillage

With a click-click and we’re wrestling

Scrambling for the weapon, decrepit mettlesome

Looking up to the heavens with a bullet in his chest

Adrenaline kicking in

– “Virgin Criminal,” The Murlocs

Much like the settlers of the American West, early pioneers in the Australian bush would also form their own folkhero archetype, the bushranger.

The ideal of a bushranging individual evokes “Australiana” pre-Federation. Such true-blue Aussie ideal is represented in “Waltzing Matilda,” the country’s unofficial national anthem. However, names like Ned Kelly and Mad Dog Morgan invoke a similar zeitgest to colonial past as Billy the Kid or Butch Cassidy, inspiring cultural products. Where Americans have Young Guns I and II, the Australians have Mad Dog Morgan seventies Ozploitation film starring Dennis Hopper as the title character.

Kenny-Smith is no stranger to this tale. The vagabond’s life forms the basis for the rattling chorus of “Billabong Valley” from Flying Microtonal Banana. The interpolated narrative describes the stakes of an outlaw on the run, an icon akin to the desperadoes and cattle-rustlers in the American West.

Contextualized in modern historiography (one that essentially no longer ignores indigenous testimony), these pioneer figures take on a more problematic image as invaders. To sidestep this double truth, the modernized tale takes a turn on the established mythos: the Rapscallion flees to the city, not the bush. The countryside is not the means of escape for this country borne character. He’s citybound, a black sheep ready to make himself anonymous in the metropolitan.

The move into the city accompanies a brewing moral ambivalence; a virgin murderer, a lovesick junkie, a scrapyard hoodlum, Kenny-Smith crafts each song’s lyrics to tailor a character without direction but with burgeoning impulses in a reality warped by homelessness.

And that’s where the totem of youth comes in.

Smith admits that, while his own youthful experience played into the storyline, “some friends experienced them in a lot more extreme sense. So I was just channeling all those stories together into this character.”

This city-slicker direction is reflected in the music. Rather than delving into the pastoral bluegrass of the countryside, they stick to the urban grime of garage rock. Shortal and company follow the standard Murlocs modus operandi, constructing a fast-paced blues psychedelia out of DIY synthesizers and garage punk acoustics.

The holotype track is “Living Under a Rock.” The riffwork romps on an off-kilter rhythm from the off. Blach fills back-and-forth on a four-four rhythm. Craig’s bass bubbles in the space between each verse. Karmouche colors the sea-saw swagger with synthesizers like a theremin. It’s fantastic to the point that “Subsidiary,” “Bellarine Ballerina” and “Bobbing And Weaving” seem redundant at best, belaboring the point at worst.

The change comes come during a slower tempo. When the cuts slow down, they reveal an inflection point on the Rapscallion’s journey. These choices are like a subconscious sign to listen, whereas the continuous flow of manic garage earlier would tune people out. From there, Kenny-Smith imbues the character with the same introspective power he has cultivated for years within himself.

“Compos Mentis” sees the Rapscallion questioning his own sanity, which is a common theme within any Murlocs project.

It’s also a common theme with substance abuse. Read as a commentary of escape, a pit has been found; the Rapscallion lives in a literal dump, pestered by hounds and sleeping on a decrepit mattress. His first reckoning with his fate does not result in a scared straight moment, rather he resolves to find an enabling partner. A Nancy Spungen to his Sid Vicious.

Not until “The Ballad of Peggy Mae,” does the climax comes at the end of a Sid and Nancy love arc, showcasing the effect the Rapscallion’s lifestyle has on the person he loves. As it slows the tempo, it cues ambulance sirens, a country twelve-string and a slide holding notes for melancholic effect. Each mention of Peggy Mae comes with a monstrous holler, snapping listeners who were otherwise daydreaming: Peg is dead, baby. Peg is dead.

Credit the most powerful moment of catharsis on the album to images of the Hollywood superego, Kenny-Smith’s haunting howls and yelps or Shortal’s breathy guitarwork, if you want. For his part, Kenny-Smith credits the album writ-large to an element more rare than film, history, place or self-knowledge. To him, the key to an album working well is: artistic synchronicity.

“I think it’s the combination of my voice and Cal’s guitar tones working well in a gritty way,” he says, “I hope that sounds authentic because, to me, it feels that way. And that’s just how we naturally make music together.”

Whatever the credit, Kenny-Smith’s waxing on authenticity is a reminder to look beyond good or bad. Regardless of Rapscallion Side Two outclassing the first with a greater diversity in composition, it features a lyricist-guitarist combination flourishing as they indulge in nostalgia for a more visceral age.

It can be hard to remember, but sometimes that’s all an album needs to do.

My heart is breaking now as I’m tearing up

She’s lying there motionless, getting too much

So I jump out of the big red bus

and I blame myself everyday

But I can’t in any way

Bring back My Peggy Mae.

– “Ballad of Peggy Mae,” The Murlocs

A CONVERSATION WITH THE MURLOCS

Atwood Magazine: The “Feral Kid” in the story of Rapscallion has a sort of nascent bushranger influence. He reminds me a little bit of Mad Dog Morgan or Ned Kelly. How do you think Australian folk icons kind of intersect with this story?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: There’s definitely a fair amount of, like, Australiana influences… but it’s sort of just like, a natural thing to go off without realizing if it’s “Australian” or not.

You can't even put a number or percent to that unknown quantity of environment seeping in, if at all.

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: I hope I painted that picture well enough to take the listener into an urban country, Australian setting… I think it’s the combination of my voice and Cal’s guitar tones working well in a gritty way. I hope that sounds authentic because, to me, it feels that way. And that’s just how we naturally make music together.

What were the challenges of going from an introspective songwriting and lyric writing style towards a more narrative-based lyricism?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: It was super rewarding the whole way through, and really satisfying when the whole land was laid out. Cal wrote all the music for Rapscallion. So he was sending me tracks very quickly… showing his true potential of songwriting and his creativity. It really helped me easily find the inspiration and influence to start writing this whole storyline.

It just sort of seemed to make sense, especially at a time when it was the early stages of lockdowns and stuff in 2020. I knew no one wanted to hear about me struggling to find toilet paper at the supermarket or go for a walk around the street before curfew. So I just had to channel that vibe and it got me excited and invested into it.

I grew up as a passionate skateboarder so I was always out the door, getting on buses, or hitchhiking or getting trains so there’s sort of elements and parts of songs throughout the album that are true in some ways, I did experience these sorts of scenarios. But some friends experienced them in a lot more extreme sense. So I was just channeling all those stories together into this character.

When it comes to writing short stories, do you do that a lot? Do you do it often? Have you ever done this before with King Gizzard or for yourself?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: Nah. Because Gizzard work at such a fast pace with everything. It’s always hard to find enough time to focus and make something as interesting as I think I could be capable of—but that’s just the nature of it. Even today, I’m gonna go to the studio after this and start trying to write stuff for Gizzard because there’s always heaps of music there.

We’re always creating, but with this Murlocs album I was working on Gizz stuff for most of the day, and then I would stop, and then I would sit down and write just lyrics. I’m lucky that I have the best of both worlds. But I’d definitely like to have more time at some point in my life to write more short stories.

As I get older, I start to realize that I’ve always known that I’m just more of a wordsmith or lyricist, and performer, first and foremost, rather than like a musician. And that’s always been my strong point. And it’s been sort of utilized and encouraged the most between both bands. I’ve always spent more time in lyrics than the music side of things.

The approach to this record reminds me a lot of Eyes Like the Sky. It's a very self contained narrative. Because this album itself was formulated during the depths of COVID, did these songs help release a “Feral Kid” impulse to get out and run away?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: One of the nicest things to reflect about back on COVID and lockdowns is that I had this vessel to escape all those sorts of thoughts. The process of writing this album was really exciting at the time because it definitely helped a lot with my mental health. To just sort of take myself elsewhere.

And it was fun because, like “Ballerina Ballerina” is about hitchhiking, getting picked up by random, sus, sketchy dudes on the road, to running and hiding under seats from ticket inspectors on trains, and then being in a city and experiencing a whole new world… exploring the city on their own without a guardian. I had a lot of fun reminiscing and chasing those feelings of my youth and those real life experiences when you couldn’t have much real life experience at the time.

The single that most affected me was ''Compos Mentis.'' It questions the Rapscallion’s sanity. How do you feel this character fares mentally? Do you see him as an ethical antihero? Or does he become a straight up villain?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: I see him as a still pretty ethical antihero. He’s just sort of finding himself, he’s just sort of dabbling in all different terrains and seeing what works best for him, or what doesn’t. “Compos Mentis” is in the middle of the album, almost like he’s starting to just realize he’s out on his own, in the unknown and doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, and what’s around the corner.

Do you think this “Feral Kid” or Rapscallion comes out a bit of yourself when you're performing live? A vessel for channeling that energy?

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: Definitely had a lot of energy when I was younger, so I definitely need to channel that state of mind when I’m on stage. I was always very active and covered in scabs and stunk like shit, and like, had tinea on my feet constantly. I was pretty, pretty gross. And I loved it. Whereas these days, just like a bit too clean cut.

You're a young urban professional now.

Ambrose Kenny-Smith: Yeah, a young, boring, 30 year old slob.

Those are more or less the thoughts I would have expressed in a singular review for Rapscallion.

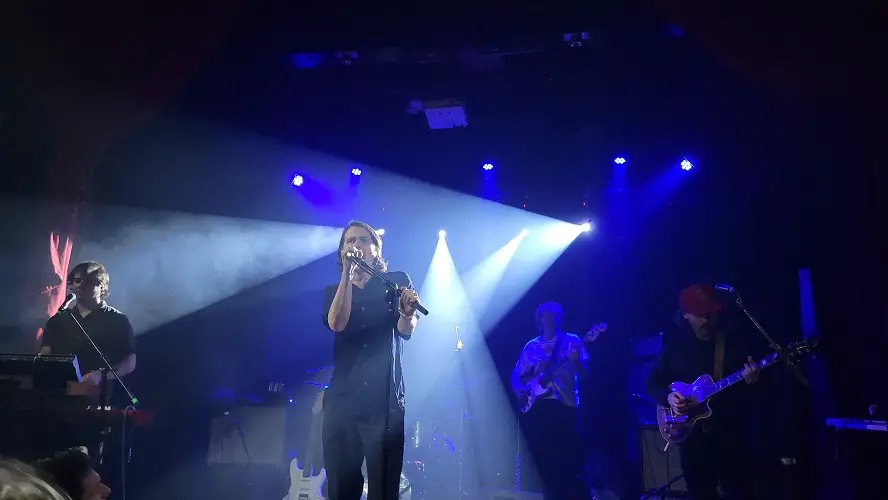

That review was overruled by a mental health episode. A shame, because in Kenny-Smith’s own post-show words, “that was a pretty good conversation, aye?”

And he was right.

Sweat drying from a monster set at the Star Theater in Portland, I felt the least I owed him was an apology for never publishing this before the release of Rapscallion. Walking home on that dry November eve, my conscience cleared somewhat as I resolved to continue a break from writing about music.

(I was still am pissed I missed my date with King Gizzard in October, though. Some scars still sting.)

Rip it off like a bandaid when you gonna come out of your cave

How can I paraphrase it? It’s overpassed, belated

Silence discomfiture, defeated, totally conquered

Put it on the backseat burner but don’t let it simmer too long

– “Undone and Unashamed,” The Murlocs

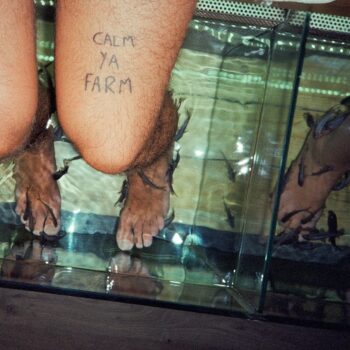

In April, however, I received a note from Sarah Avrin, The Murlocs’ public relations contact in the U.S., asking if it were possible for me to pick up coverage again for a new Murlocs record, Calm Ya Farm.

Shock ran through every vein in my body. I thought my anxious breakdown and descent into radio silence had been the journalistic equivalent of taking twelves barrels of gasoline and a match to this professional bridge. As it turned out, it just went without maintenance. The bridge still carried traffic and with it came another chance to write about Australia’s golden generation in music.

The seven intervening months from the release of Rapscallion constituted a ride for Kenny-Smith; releasing three new albums with King Gizzard in October, committing to a residency tour of the United States, gearing up for another European tour and following it all up with Calm Ya Farm and the recently released PetroDragonic Apocalypse; or the absurdly long title that I’m not going to bother to repeat.

It was in the midst of this absurd touring schedule where tragedy struck; Kenny-Smith’s father, Broderick Smith, passed away. To say Broderick Smith had an influence on the musicality of his son and Murlocs and his son is to understate the matter. His band, The Dingoes, are in many ways the spiritual predecessor to the Murlocs.

And that harmonica tone is carried on with his son.

But with his passing so fresh, this was not the time to dig into it. So I agreed to cover Calm Ya Farm with a sight to express condolences and pick brains with Shortal via email. Our exchange was brief, but the answers illuminated Shortal’s feelings on the progress the Murlocs have, of the talent they’ve shown.

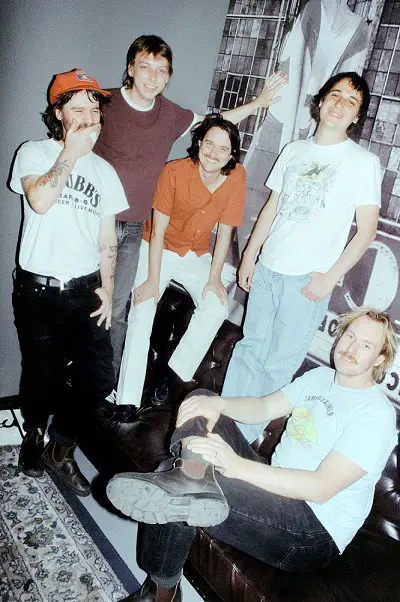

Of talent, there can be no doubt. Members of The Murlocs can be described as Flightless Records all-stars; every member has been affiliated with the independent label during its period of meteoric growth in notoriety.

Kenny-Smith and Craig have the connection with label founder Eric Moore through King Gizzard, but the Murlocs has always been Kenny-Smith’s main creative outlet. Craig collaborates with the former and latter, but he creates under the Pipe-eye cognomen. Blach, for his part, provides the percussive backbone of Beans’ debut efforts on Flightless.

Karmouche meanwhile, took the rambler’s path. Karmouche first played with Craig in the jazz-fusion outfit Dreamin’ Wild before producing two albums as Crepes. Both albums were released on a fellow Australian independent label, Spunk Records, but were recorded at Flightless’ studios. It was during that time he began contributing keyboard parts to Old Locomotive, helping the band reach the ARIA charts for the first time in their career.

Running on seven years from the release of Old Locomotive, the band has repeatedly put the “side-project” myth to rest by virtue of a body of work that adds something new every year for three years running. The latest result is Calm Ya Farm. A brilliant batch of music formulated more or less alongside the material for Rapscallion.

“This was the second record we did in isolation,” Shortal said.

“After Rapscallion we had a bunch of songs that didn’t quite make sense with that album at the time. But also knew they were always worthy.”

The material was replete with country-rock references from the Rolling Stones, Jim Ford, and Ronnie Lane and Slim Chance.

The album starts strong with a cool devil-may-care country sway of “Initiative;” its opening piano prances to a folksy slide guitar tone and a swanky rhythm. As Kenny-Smith supplies, it’s a song about getting your shit together. Be it to reach that next goal or just to enjoy a life worth living. Tim Karmouche’s piano is unflappable in its accompaniment.

The album being a sped-up garage blues update to Anymore For Anymore notwithstanding — saxophone included — The Murlocs have never sounded more country. It’s only a bummer if you consider Rapscallion as a tale of country-to-city migration. A dash more of this schmoozing country sleaze might have done well to illustrate that change in setting.

Nevertheless, the period of incubation was vital. Where the slapdash sonic of Rapscallion lent itself well to shining a light on Kenny-Smith’s abilities as a storyteller, the opening salvo of songs spin in circles. Energetic and off-kilter as they may be, the mixing focuses heavily on Shortal’s guitar and Blach’s drumming.

This is not the case for Calm Ya Farm. Album opener “Initiative” begins more or less with a barstool pianoline from Karmouche, swaggering with a whiskey bottle confidence. That confidence carries through damn near the entire album. Picking out a singular highlight is impossible. Forget Ronnie Lane and Slim Chance, it’s effort after effort that would make Elton John and Bernie Taupin blush. And if you can garner a comparison to the deepcut Tumbleweed Connection album, you must be cooking on the keys.

In an email interview, Shortal reflected on the skills of Karmouche, calling him “an absolute weapon on keys but also guitar and vocals,” who helped bring the “calm ya farm attitude” to life.

Craig, too, shines. “An unbelievable multi-instrumentalist” able to play back anything laid down, he provides for no less than 13 instruments on the record, 17 if you count different mellotron patches. His utility on this record is damn near unmatched.

“Russian Roulette” is the personal favourite, with Craig cooking on dobro and Karmouche gone full wizard with the organ. A skitter-scatter nerve of energy menaces the whole thing. Shortal smartly links up his guitar with Craig’s dobro, as Craig switches to the bass for another powergroove. Actually it’s not just “another” powergroove. It’s best damn bass moment on the entire album and dare I say Craig’s career.

“We’ve been a band for over 10 years now so naturally we’ve all grown as musicians and humans,” Shortal says of the Murlocs, “since we all play with many different groups, we can all bring something to the table from many different angles.”

“I feel like this record was the most collaborative we’ve ever produced,” Shortal followed-up.

Almost lost control, lord knows we tried

Ten years plateaued, together we survived

– “Queen Pinkie,” The Murlocs

To this point, I have some (mostly) unedited notes that categorically represent the excitement and collaboration that shines through so immediately on the album.

The first comes with Kenny-Smith’s classic sawing harmonica and blues riffwork introduce the tried-and-true Murlocs aesthetic on “Common Sense Civilian.” Blach’s cymbal crashes and Karmouche’s piano emphasize it. Meanwhile, Craig’s arachnid bass and clavinet transforms the rhythm into a powergroove. It all comes together with an abbreviated blues cruise bridge, a mini-jam delight with Kenny-Smith wailing on the tin and Shortal pouring on the bourbon-coated licks.

Kenny-Smith, for his part, waxes on the polarized movements of the Anglophone world: politics becoming identity, a declining ability to parse information and some severely ungrounded theorycrafting. It’s a song directed to the demagogues among us. Not just the Trumps or the Morrisons or the Johnsons, but the blind leading the blind.

“Undone and Unashamed” is Blach’s time to shine. The drums move into the forefront of the mix. Gnashing his kit while Cook’s bassline growls, the rhythm is as snazzy as it is mean. Blach drums like he means it. Using a hi-hat like clockwork. Everyone else plays like money, too. Shortal’s showcases another phenomenal set of riffs, but it’s Blach who tees it all up for a saucy sax solo from Kenny-Smith.

The song which deserves all the flowers on the record, however, is “Queen Pinky.”

A ballad penned to Kenny-Smith’s partner, the piano from Karmouche is untouchable. Just the perfect amount of dramatic romantics dancing key-by-key, introducing the emotion, punctuating the verses and accompanying the chorus. Craig connects that piano melody to his own farfisa and clavinet parts, all the while providing a subdued but soulful bass.

All in all, the opening seven form a murderer’s row of killer after killer. That’s not to call it filler beyond “Undone and Unashamed;” the back catalogue just reserves the right to wander, kicking out the anthems, reflections and the jams. Personal reservations of the lackadaisical “Catfish” aside, the band is damn near undefeated on Calm Ya Farm, bobbing and weaving as a cohesive unit of five rather than revolving around the centrifugal force of the Smith-Shortal partnership. Rapscallion may exhibit more lyrical growth over musical, but Calm Ya Farm covers the musical evolution just fine.

So make no mistake: the Murlocs are not some side-project. They release too much music, they tour way too extensively, and there last two albums rock just too damn hard. To say different is to call the sweat on Kenny-Smith and company’s brow less than true blue rock and roll.

I’m as a mad as a hatter,

Officially off my rocker

But hey I couldn’t be gladder

I’m just lucky to still be here singing

– “Initiative,” The Murlocs

— —

:: stream/purchase XXX here ::

:: connect with XXX here ::

— — — —

Connect to The Murlocs on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Izzie Austin

:: Stream The Murlocs ::

© Izzie Austin

© Izzie Austin