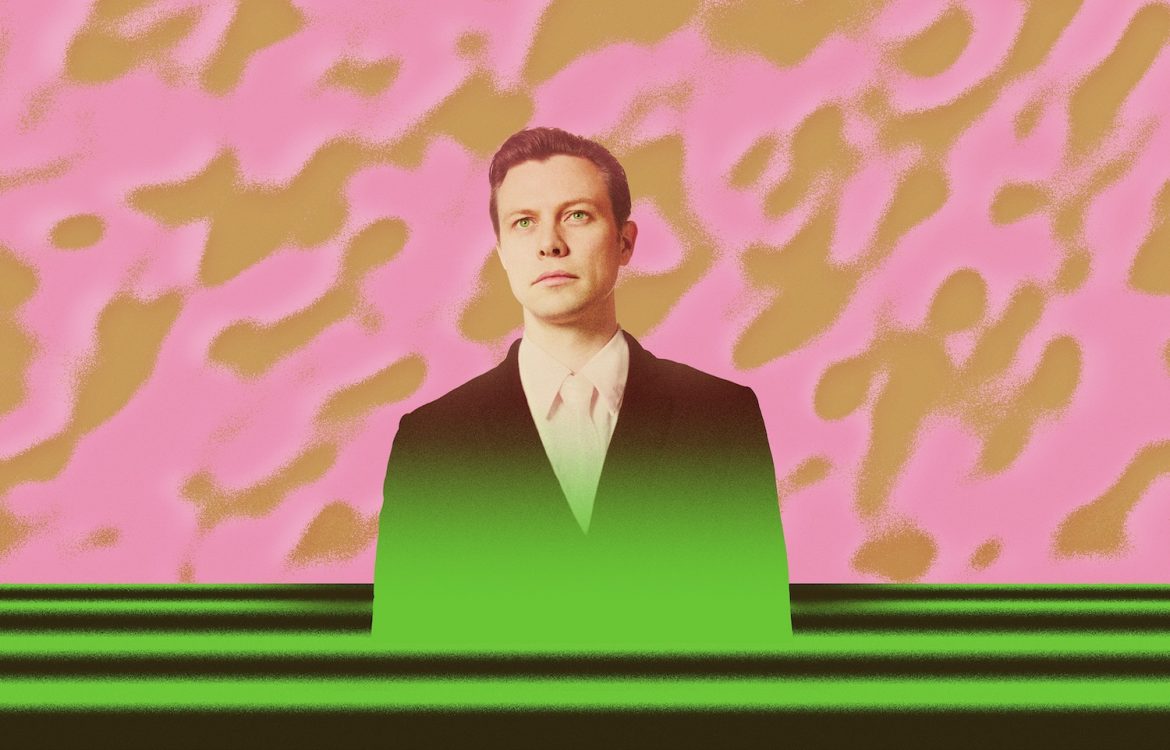

A moving art pop exploration of humanity in the digital and electronic spaces, Anthonie Tonnon’s third LP ‘Leave Love Out of This’ comes to life with more questions than answers, pressing us to consider the world(s) we live in, our relationship(s) with our surroundings, and beyond.

for fans of Beirut, San Fermin, Bahamas

Stream: “Entertainment” – Anthonie Tonnon

I was interested in 808s and other electronic instruments, but I wanted to find ways to play them with a sense of musicality and fragility. I wanted to find meeting places between organic and synthesized sound.

Expansive, immersive, and sweeping, Anthonie Tonnon’s latest album feels as grand and majestic as it does intimate and definitively of-the-present. A moving art pop exploration of humanity in the digital and electronic spaces, Leave Love Out of This comes to life with more questions than answers, pressing us to consider the world(s) we live in, our relationship(s) with our surroundings, and beyond.

Julie you saved me

when you put me on the screen

I had become a great sportsman

stranded on fledgling teams

you were the one to convince me

to take the money

sell any dream

that could be used against me

so I didn’t wait for the injuries to take me, well

our people didn’t ask for an interview

our people aren’t afraid of some higher minded truth

just entertainment

I was just a kid

with a perfect kicking leg

and what passed for an education

you gave me a shot and I’ll always remember that

Released July 16, 2021 via Nadia Reid’s Slow Time Records & Misra Records, Leave Love Out of This is incredibly epic in scope, vision, and scale, while remaining a surprisingly vulnerable, relatable, and accessible record. The follow-up to 2015’s sophomore LP Successor finds Anthonie Tonnon working with bandmate and longtime collaborator Jonathan Pearce (of The Beths) to create a collection of songs that extends well beyond the bounds of whatever player is being used to transmit sound to the ears.

The New Zealand-based artist often blends music, art, and advocacy in his work, using live performance to experiment with new technologies and ideas – and Leave Love Out of This is no exception: Through eight vast, visceral, textured songs, Tonnon plunges into concepts of purpose and being, humanity’s future and our collective past, the immediacy of life in the moment, and the seeming futility that sets in when we begin to zoom out. Leave Love Out of This isn’t meant to be conceptual, and yet listeners may well come out of it with a reinvigorated, renewed sense of self – or at the very least, an appreciation for life’s grandeur and sheer wonder. Reminiscent of artists like Beirut, San Fermin, and Bahamas – who run the gamut of classifications (from indie rock and chamber pop to folk, electronic, and singer/songwriter) – Tonnon’s multi-dimensional music is inspiring and thought-provoking, elegant and graceful, and in instances, jaw-droppingly beautiful.

As the artist himself relates, this album is quite a long time coming. “Jonathan Pearce and I started Leave Love Out Of This during a period of time where I was touring a lot, and I was starting to experiment with drum machines, sampling and other electronic elements – mostly as a way to expand my live show,” Tonnon tells Atwood Magazine. “The experimentation led me to unexpected places – I ended up creating a show called A Synthesized Universe for planetariums. When making a video for one of the songs, ’Old Images,’ I became suddenly and quite deeply interested in New Zealand’s former public transport system. Having done one immersive show, I created another called Rail Land, where the audience travelled with me on trains to old community halls.”

“It’s true I was getting deviated from making an album, but it was fulfilling work, and the new approaches and technology were also changing the album as we were recording it. But more changed too. Jonathan’s band, The Beths made a great and successful album, and started touring full time. I also moved from Auckland to Whanganui, so Jonathan and I started working by distance. Of course, that turned out to be a good skill to gain. The project feels like a generation ship – we’re leaving it as different people with different lives, in a different world.”

As far as visions are concerned, Tonnon kept his loose – allowing for plenty of experimentation with lyrical themes, performances styles, and instrumentation. “I had a few inclinations when I started,” he explains. “I was interested in writing songs by starting with a beat, rather than chords. I was interested in 808s and other electronic instruments, but I wanted to find ways to play them with a sense of musicality and fragility. I wanted to find meeting places between organic and synthesized sound. I’m always trying to make a kind of pop music, and I wanted to strip the lyrics back further than I previously had – to their essentials, which was a terrible challenge. I try not to hold on to too much of a vision, I just hammered away at those inclinations and started performing shows to see how they played out.”

“My biggest influences have always been the musicians around me and in the generation before me in New Zealand. You’ll never understand a great song better than if your friend writes it. I grew up in Dunedin alongside some great artists I wish more people knew, like Haunted Love. When I was at university, I was really influenced by shows put on by bands from other cities like The Phoenix Foundation, Lawrence Arabia and The Ruby Suns. I’ve toured with some of my heroes like The Chills, The Veils, and Don McGlashan. Nadia Reid, who runs Slow Time Records is a great friend and influence, also from Dunedin, and I’ve probably learned more about music from Jonathan Pearce than any canonical band.”

Only looking through

old images

do I understand

she carries albums in her mind

from another time

when the sun gave light in a different tint

her mother wearing hazel print

and though some remember doubt and fear

she remembers colourful years

and I’m not so radical

I still have my affinities

for the twentieth century

I have a driver’s license and one day

I will drive her to the city that left this mark on me…

here’s a photograph

of a young girl looking shyly into the camera

wearing a shirt that reads Australia

holding a rare butterfly in her hands

and I wish that I could visit there

be the air around her

hear the secrets she might tell

then but not now

Embarking on the great forty-minute journey through Leave Love Out of This doesn’t inherently require an understanding of Tonnon’s album title, but hearing his explanation sheds light not only on his background, but also on the perspective he carried with him throughout the writing and recording process. As we come to see, the incredibly human reckonings with modernism and technology that abound within and throughout this record are a natural response, or reaction to the world, as he sees it, around him:

“I’m the first generation to grow up in the new economic system New Zealand adopted in the ’80s,” he says. “That system rests on hypothetically rational actors who act in their interest with good information. If you follow that logic, as economics departments do, you end up with a machine-like view of people. I think the idea for my generation was that by growing up without the distorted information from humanism or the welfare state, we would become perfect rational actors and thrive. That’s darkly comical now, given the intergenerational inequality we’re now dealing with. But it also feels to me like we can’t go back to that humanist world, because for my generation – we don’t really understand it. We’re a generation trained to be cold human calculators, but we struggle to do things differently even when we know the system isn’t working for us.”

Bring no history

bring no secrets with you

we will put nothing at risk

spend an evening singing

in the war room

but leave love out of this

and when you’re speaking, speak in

present tenses

stay in a moment that exists

the future is irrelevant here

the past isn’t missed

so leave love out of this

leave love

to someone who believes in it

Tonnon cites a few lyrics in particular that left their marks on him: “I’m really happy with a couple of lyrics,” he says. “‘Two Free Hands’ uses very few words, but manages to sweep across eons of time, take on evolution and the future of work, and do it all through the character of a careers counselor.”

Ask her what she’d like to be

and she stares at her hands

ten million years passing by in my mind

the suspension in the arches of her feet

the development of her spine

that led her to stand

with two free hands

“I think my favourite lines are in ‘Mataura Paper Mill,'” Tonnon adds. “It’s about a paper mill that was mothballed in the year 2000. Mothballing is supposed to retain the possibilities of an asset like that – but within 15 years, the paper mill was being used to warehouse toxic waste, by a company who could simply declare bankruptcy (in New Zealand, but not overseas) to escape their liabilities.”

Mataura Paper Mill

hearts are lost in the detail

some protest, others not at all

what greater minds decide to mothball

and greater minds will always cross this bridge

to give their promise to the council

and greater minds always incorporate

so that no one can be held responsible

Highlights are easy to come by for listener and artist alike, and the more you experience this album, the more there is to take away from it – such as the stark contrast between opener “Entertainment,” and the poignant elegy of closer, “Mataura Paper Mill” and its breathtakingly bittersweet final cries of “Come on, come on, come on…” In between these two bookends, Tonnon’s audience is treated to a melting pot of electronic and organic sounds that coalesce with impressive synergy, whether on the heartfelt thoughts and observations in “Two Free Hands,” the dramatic strings and great heights of “Old Images,” or the anthemic radiance achieved in the songs “Leave Love Out of This,” “When I’m Wrong,” and “Peacetime Orders.” Pulling up the veil on each of Tonnon’s songs takes time and patience, but turns into a rewarding process as nuanced reflections and deep emotions take shape with repeated exposure.

Just like all pieces of art, you ultimately get out of music what you’re willing to put into it – and this collection has a tremendous amount to give. Experience the full record via our below stream, and peek inside Anthonie Tonnon’s Leave Love Out of This with Atwood Magazine as the artist goes track-by-track through the music and lyrics of his third LP!

— —

:: stream/purchase Anthonie Tonnon here ::

Stream: ‘Leave Love Out of This’ – Anthonie Tonnon

:: Inside Leave Love Out of This ::

— —

Entertainment

When I was a bartender, one evening I finished my shift, and somehow got talking to a New Zealand sports star and television host. He started chatting to me in the Mens, and next thing I knew he was buying me vodkas and telling me about his life – how he’d become financially independent at 16, his choices in life, that sort of thing. His values were very different from mine, but it was an interesting evening, and he was a generous guy. A few years later, a current affairs television show I admired was cancelled in a very public shake-up of a TV network. I was shocked, and so were many in my left-leaning bubble in Auckland. A culture war had begun over what provincial New Zealand really wanted on its screens, and my side was losing.

I wanted to be able to see the issue from the other side. So – I started thinking about the sports star; I knew he’d sit on the other side of that debate, and I wanted to imagine what he might say over a vodka.

Two Free Hands

‘Two Free Hands’ is about a careers counsellor going through a crisis: how do you advise students when society is in existential crisis, and when, by the time those students leave school, the jobs might be gone? When I was writing this, I was reading a lot about early humans, and I was fascinated by the idea that, when we started walking on two legs, we gave ourselves this terrible opportunity and burden – what do we do with our hands now they are free?

Old Images

‘Old Images’ is a love song. It came looking through film photographs in my wife, Karlya’s family albums. It’s also about the last years of the Cold War, and an attempt to understand the world from the vantage point of another generation – my parents’ generation. They started their families and bought their houses and cars in the shadow of the Cold War.

I have a memory from the early 90s – a map of the world in a school classroom. I remember my teacher telling me that the USSR on the map was about to be taken away. In the early 90s, New Zealand may not have changed as much as the former Soviet Union, but we were going through a pretty fundamental upheaval.

My dad is a tradesman who renovated a lot of houses, and I used to travel with him in the truck to the demolition yard, where he would buy railway sleepers for landscaping. I went with him to the Chief Post Office in Dunedin, where the new private owners were selling the interior to anyone who could remove it fast enough. Until we made the music video for this song, I didn’t quite click that my dad was renovating Dunedin suburbs using the resources of the state – resources sold at scrap prices during the sell-offs of the railways and other state assets.

Leave Love Out Of This

This was the first song I wrote for the album. It took two years – longer if you count the ending and guitar solo – which came out of experimentation for live shows. I started with the melody first, which was new to me at the time, but almost all the songs on the album were written this way.

The title is a return to a common theme for me. I’m the first generation to grow up in the new economic system New Zealand adopted in the 80s. I think the architects of that system thought we would grow to be perfect rational calculators – unencumbered by humanist sentimentality, ready to engage with the pure mathematics. And I wonder if the economic system has shaped our minds differently. When I entered the workforce, I found I was quite good at negotiating with the boss one-on-one, but colleagues who had grown up with unions found it more difficult. But little good it has done us – and given the situation of many my age, the idea that we were set up to succeed seems a bit of a cruel trick.

When I’m Wrong

There was a period where I was touring quite relentlessly, and I wrote this lyric on a longhaul flight – either to or from home. Karlya and I had a ‘six-week rule’ at the time – where if the tour was going to last more than six weeks, she had to come. I think we’re down to about a one-week rule now. The stresses of international touring are terrifying. When you’re dealing with the amount of things that could go wrong outside of your support network – you can feel like you’re on a very small boat in an open ocean storm.

When I lived in Auckland, I worked a stream of part-time jobs, always trying to work as few hours as I could survive on, so that I could spend more time writing music, or on the road. I saw myself reflected during the four tours I did of the USA. I met people my age trying to forge some sort of creative life in American cities – ‘all the young and talented indentured to their dreams.’ Often, I found those who seemed happiest were the ones who had given up on NYC or LA, and had chosen cheaper cities – places like St Louis, New Orleans or Minneapolis, where they could get closer to being full-time artists. I thought a lot about the way Americans vote with their feet, and it had an influence on us when we moved from Auckland to Whanganui.

Christopher

One of the strangest places I played in the USA was in South Bend, Indiana, where The University of Notre Dame is. I played in an old dormitory pool which had been turned into a performance space. I played to a surprising mixture of college kids, some on the very liberal end of the spectrum, and others who were there on military scholarships and clearly quite religious. I ended up going to Taco Bell with a few of the more conservative ones, and eating burritos on the bonnet of a car. I felt there was a lot of tension among the guys – they were torn between being young, in college, maybe wanting to fall in love – and the strict codes they’d signed up to, between the military and their faith. There was also a class tension – the military scholarship kids came from poor families, but they told me that when football games were on, some students and relatives would arrive on private planes. It was a nice night, and I really liked South Bend, but I felt some danger in those kinds of tensions.

Peacetime Orders

One time on tour, my friend Shenandoah Davis took me to Marin County – the wealthy ex-hippy area on the other side of the Golden Gate bridge. We ate the most expensive lunch I ever bought in America, and got talking to a guy who said a few things about the conspiracist left worldview growing in that area. We were looking at the Pacific, and he told me that the residents of Marin County were concerned about water from Fukushima making its way across to California. It was the starting point for a song which took a long time to find its ending.

By the time I finished it, the song had become an allegory for the disappointments of the Obama years, the frustrations with consensus politics, and the darker places those frustrations can lead to. Playing the song live, I came across this dark instrumental march that grew its own momentum, and seemed to pull the rest of the song into it.

Mataura Paper Mill

On tour, I’m always looking for those sites of decaying industry you see in de-industrialised countries. Old power plants and dormant factories at epic scales – 20th Century answers to the pyramids. I was on tour with The Chills, and we took a shortcut over the Mataura Bridge to get to Invercargill. From the back of the van, and for the first time I remember, I really noticed what must be New Zealand’s most epic monument to de-industrialisation – the Mataura Paper Mill. The mill hovers above a waterfall on a scale that seems unbelievable for a town of 2000 people. The image stuck in my mind, and when I got home I started doing some research about the Mill. What I found out was unbelievable.

Only closed in the year 2000 (in a company rationalisation by future Trump aide Chris Liddell), the Mataura Paper Mill went from being the town’s major employer, and a producer of some of the world’s best paper, to being used to store toxic waste. Most depressing was the way the companies involved were able to incorporate themselves in such a way that they could declare bankruptcy when they lost their contracts, leave Mataura with the waste, and yet keep operating overseas. After some really close calls, the waste is now out of the mill – mostly at local and central government expense. But much of the waste remains in other locations in Southland, and we haven’t dealt with the regulatory conditions that allowed this to happen.

Lockheed Bomber

This song is about an air accident that happened in Australia in 1940. I became interested in an era of wealthy aviators in the 1920s and 1930s – people who bought their own planes and built their own airstrips, at a time when the industry had little regulation, and a terrible safety record. As a 7-minute, through-composed episode on this album, there’s something about the hubris, and the misplaced tenacity of the main character, that connects it to the other songs on the record. It felt good to give this a proper band ending – the drum machines are gone, the tempo is speeding up and slowing down and the album finishes with an almighty, screaming crash.

— —

:: stream/purchase Anthonie Tonnon here ::

— — — —

Connect to Anthonie Tonnon on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © 2021

:: Stream Anthonie Tonnon ::