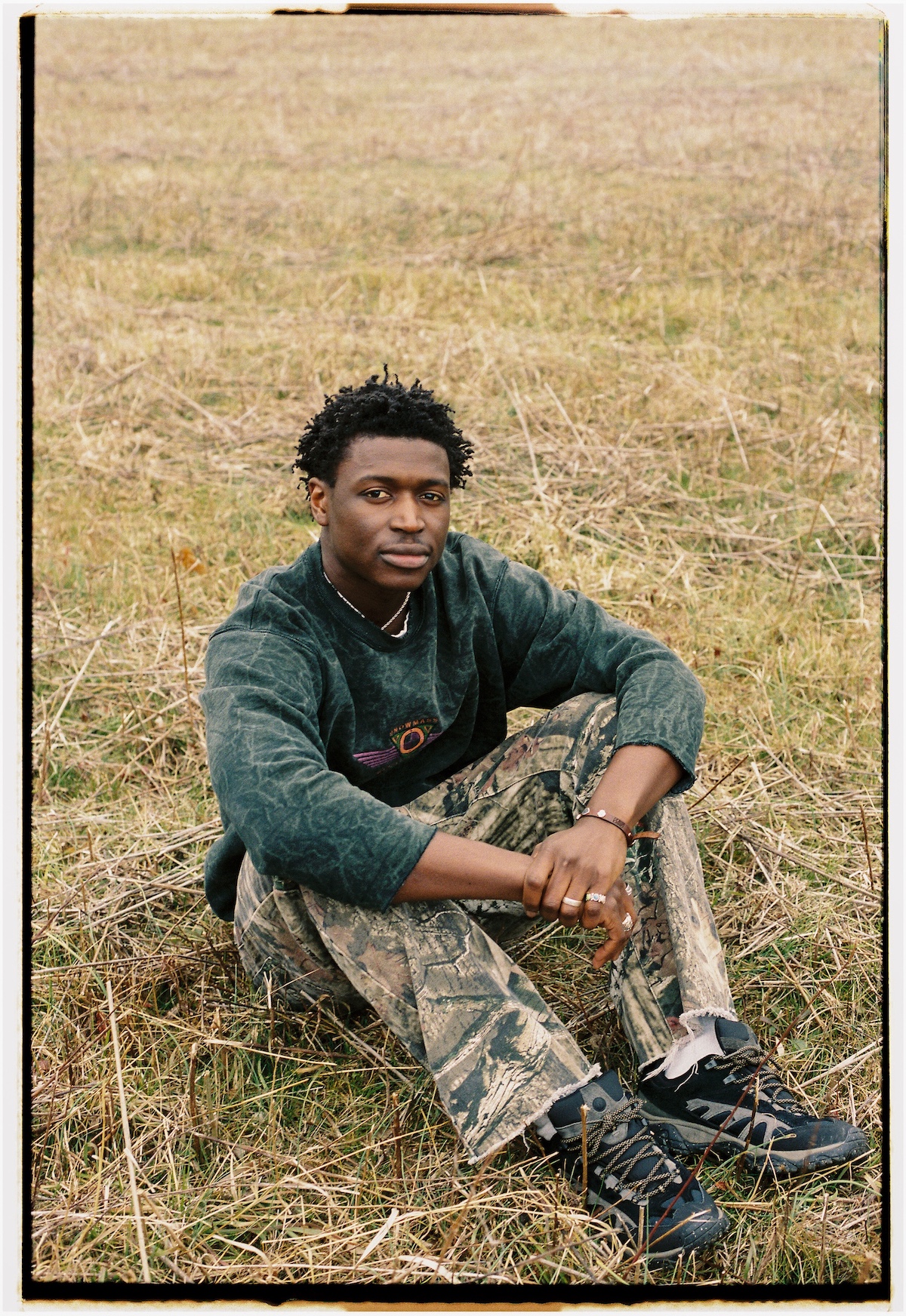

Mon Rovîa’s breathtakingly beautiful debut ‘Bloodline’ is a searching, deeply human album that weaves memory, lineage, protest, and care into a living companion – an intimate indie folk journey through suffering and self-discovery that holds fast to love, hope, and empathy, inviting us to leave the world a little better than we found it.

Stream: ‘Bloodline’ – Mon Rovîa

There’s a particular kind of quiet that settles in when a Mon Rovîa song begins – not silence, but space.

Space to breathe, to listen, to recognize yourself in someone else’s voice. From the first notes of Bloodline, released January 9th, 2026 via Nettwerk, that familiar warmth returns: Folk built on tender harmonies, gentle melodies, and an ache that feels lived-in rather than performed. This is music that doesn’t rush to impress. It opens its hands slowly, inviting you to step inside.

But what makes Bloodline feel so striking isn’t only how soothing it sounds. It’s what that softness is doing. Mon Rovîa writes with the calm conviction of someone trying to leave the world a little more human than he found it – and if the album often feels spellbinding, it’s because his songs are built like lanterns: Warm enough to hold, bright enough to see by, steady enough to follow when everything else feels unstable.

“My debut album, Bloodline, is now yours,” he writes. “May it be a companion for you as you go through. Thank you for the love along this road. I hold you all close in these times. Remember, life does not have to end with suffering.” It’s a simple offering, but it sets the emotional terms of the record: This isn’t music that asks to be admired from afar. It wants to sit beside you.

Bloodline doesn’t emerge from nowhere. It carries the weight of a life shaped by movement, fracture, and inheritance long before it ever became an album. Born in Liberia and now rooted in Tennessee, Mon Rovîa grew up in the long shadow of war, displacement, and unanswered questions about origin. Adoption placed distance between him and his earliest history, but it never erased the pull of it. Instead, that space became a quiet gravity – one that draws his songwriting back, again and again, to ideas of lineage, belonging, and the cost of becoming yourself without a full map of where you came from.

“When the name Bloodline first came to me in 2022, I recognized it as the title of my debut album,” Mon tells Atwood Magazine. “What I didn’t realize then was how long it would take to grow into the story behind that name, the grief, the quiet, and the slow disassembly of a self that resisted its own becoming.” Even now, he says, he moves carefully through the world, “as though visibility might undo me, as though being seen might awaken an identity I’m still learning how to carry: Mon Rovîa.” Becoming, here, isn’t a declaration or a destination. It’s an intimate, ongoing act, still in motion. That tension – between visibility and vulnerability, between survival and self-definition – is the emotional engine of this record.

Before stages and sold-out rooms, Mon’s life was defined by physical work and constant motion. He spent years landscaping across Georgia and Tennessee, clocking long days under punishing heat, humming melodies to himself as a way through the hours. Those experiences didn’t disappear once music became his livelihood. They stayed embedded in how he writes – attentive to labor, dignity, exhaustion, and the quiet heroism of simply holding on.

“I’ve taken the pieces that have been hard to come through and broken, and made them into something useful,” he’s said. That instinct toward usefulness – toward turning lived experience into something that can serve others – is central to who Mon Rovîa is as an artist. His music is not designed as performance or spectacle. It is designed as encouragement.

That belief also explains why Bloodline holds personal reflection and public conscience in the same breath. Mon does not see those things as separate. For him, art isn’t neutral – it’s a way of standing up, speaking clearly, and leaving doors open rather than slamming them shut. This is why protest, tenderness, memory, and hope coexist so naturally throughout Bloodline. He isn’t interested in easy answers or polished conclusions. He is interested in telling the truth as he understands it – carefully, communally, and without turning away from discomfort.

Mon has described Bloodline as something more than a collection of tracks, framing it as both private document and shared testimony – “a sweeping and deeply personal 16-track project” shaped by “memory, identity, migration, grief, and resilience.”

That’s the album’s heart: A story that’s singular, but never sealed off. Bloodline is not just the story of where he comes from. It’s the record of someone still learning how to carry that story forward, cracking himself wide open in the process – inviting all to join him and recognize their own reflections inside it. The further Mon gets into his own history, the more he seems to widen the door for listeners to enter theirs.

And that “companion” language isn’t incidental – it’s the record’s guiding principle. It’s the thesis of Bloodline, and it’s the throughline of Mon Rovîa’s artistry. As he recently told NME, “Bloodline is the journey through my own becoming, but my hope is that it can be a companion to [listeners] on their own journey of understanding who they are and what the world is. Life doesn’t just stop at the beginning of suffering. There’s always more after.” Bloodline lives inside that “more after” – not pretending pain is elegant, but refusing to treat it as the end of the story.

One of the album’s greatest strengths is how it carries weight without hardening. Mon’s voice stays intimate even when he’s singing about enormous things: Identity, war, displacement, systems, survival. The record is deeply personal, but it refuses to become insular. It doesn’t collapse inward – it reaches outward, again and again, like that’s the only honest way to tell the truth.

That outward reach is part of why Bloodline works so powerfully as an album experience.

Mon’s songs are often quiet in a way that demands attention, and Bloodline builds an entire world out of that attention. The tracklist moves like a long conversation you don’t want to interrupt – one that returns to the same core questions from different angles, not to confuse you, but to show how layered the answers can be. You can hear it immediately.

Album opener “Black Cauldron” is a perfect early example of how Mon writes about struggle without surrendering to it. The song feels like a meditation on endurance – what it means to be shaped by what you’ve survived, and what it costs to keep going anyway. When he sings, “Whittle me ’til I’m little me, back to banyan trees, cassava leaves. War-torn screams, Maria, birthing me in a black cauldron,” it’s not triumphal. It’s devotional – a vow to keep rebuilding. Even its imagery feels elemental: “One for the Bible, two for the children with the rifles, three for survival, I’m running in the cycles… Some things, they can take you right back.” The land, the body, the spirit – all of it part of the same fight to remain whole.

The title track, “Bloodline,” makes the album’s central inquiry explicit: How do you carry what came before without letting it define your limits? Mon frames lineage as something both haunting and clarifying, singing, “Ten thousand roads I’ve walked on my own / Further I go, I’m closer to my ghost.” It’s such a quietly devastating line – the more you travel, the more your past follows. And yet the song doesn’t treat that as doom. It treats it as truth: history is not optional, but meaning is still something you can shape.

Ten thousand roads

I’ve walked on my own

Further I go

I’m closer to my ghost

Came a long way

Can’t fight my bloodline

My name still ties

My bloodline

Still, mmm, my bloodline

Dissolve what I know

Call it my own

If “Bloodline” is about inheritance as gravity, “Whose face am I” is about inheritance as question – the ache of origins, the longing to understand what you come from, and what you might still be missing. Mon doesn’t sing it like a riddle. He sings it like a human need. “Every passing mirror, I ask, whose face am I?” he repeats, letting the line become both mantra and wound.

And he’s explicit about what that searching can carry. “A lot of life is about your history,” Mon says. “The search for understanding what has happened, what is, and what isn’t. The Truth lies at the epicenter of the case. For many adopted children, or those who have lost parents when young or never knew theirs to begin with, there can be an unspoken weight. We all long to know who brought us into this world, and at what cost. Relief releases sweetly as answers come to light. Know you aren’t alone in your search for your story. Many seek with you.” That last line – “Many seek with you” – is Bloodline in miniature: A record that refuses to let anyone feel alone inside the hard questions.

I been reaching

Through lonely seasons

Trying to give meaning

To phantom feelings

Yearning in my soul

For a name I’ll never know

Hey soldier

What’d you go see her for

Was it love in the war

Or the vices of a man

Did you even know

You left something behind

Whose face am I?

Even when Mon turns toward brightness, it doesn’t feel like escape. It feels like survival in motion. “Field Song.” is the album’s most sunlit moment – claps, shouts, that heartwarming forward momentum – but it’s not “upbeat” in a shallow way. It’s upbeat like someone choosing life on purpose. The lyrics feel like sweat turned into melody: “Baby, I been working some things off / Walking round with these heavy thoughts / But I keep moving for you / I keep moving for you.”

Mon’s own story behind it makes that joy land even deeper. “Before the songs were on stages, they were sweat-born,” he shares. “I used to do landscaping across Georgia and Tennessee, long days with nothing but the beating sun above me. My hands were calloused, my back sore, and the heat pressed in like it had something to prove. I’d hum melodies and write catchy ditties that helped alleviate the true state of my current circumstances, dreaming of a day I could work under the sun of my own choosing. This song is for the one still out there, clocked in, overlooked, but still holding on to their dream. May this song help pass the time.” It’s an anthem for the unseen – not by romanticizing struggle, but by honoring the dignity inside it.

Baby I been working some things off

Tryna get right for myself

Not anybody

Thinking bout days gone by

Running near still water creek

Chasing huckleberries

Wish I was yours

But the sun been bearing badly

Tryna carry on

Still got miles to go

Don’t go forgetting on me

Don’t go forgetting on me

That same spirit runs through “Old Fort Steel Trail,” one of the album’s emotional anchors – and one of its clearest statements about refusing to stay trapped in old cycles. “This song is about circling the past one last time then choosing to lay it down and move forward. No more repeating cycles. No more grave-robbing your own spirit. Time to rise!” Mon says. The phrasing is unmistakable: Compassionate, but firm. There’s tenderness here, but also accountability.

The longer reflection he shared about the song makes it feel like a living photograph. “The road I lived on for three years near Olney Montana is set in my mind,” he says. “If it weren’t for the two boys who lived to the right of us, I don’t think the memories would have stayed as long. There was a river behind our house that ran for miles. We used to walk up it, barefoot, against the current. Our parents never asked where we were. We were one with nature, one with the hush of pine and water.”

He continues, “This song came from that river. From the dirt under my nails. From the weight of questions. I’ve been circling ever since, picking up stones, casting some, carrying others. Don’t stare too long at your mistakes without action. And once you have done the work, lay it to rest. Don’t continue grave robbing yourself. Little by little, I’m learning to put the past down.” It’s rare to hear an artist narrate memory with that kind of sensory gentleness, and then turn around and make it a directive for the soul: do the work, and then let it rest.

Old fort steel trail

Getting tired of picking up stones

Dirt in these nails

Now I’m back on the side of the road

‘Cause it’s all I’ve ever known

Outgrown my winter clothes

Is the pain the thorn or the rose?

Can you change the color of bones?

Ooh, is this a prison in my mind?

Ooh, or does a prism just need light?

All of this – the identity-search, the labor songs, the memory-rivers, the insistence on moving forward – builds toward the album’s most overtly political and culturally urgent centerpiece: “Heavy Foot.”

If Bloodline is a memoir, “Heavy Foot” is the moment it looks up, makes eye contact, and speaks directly to the world outside the window.

Mon has never hidden from the responsibility he feels. “‘Heavy Foot’ is about the moment we’re living in – the difficulties Americans face, the people and the government,” he affirms. “It’s a song about joy and resistance, telling the truth of the matter, and knowing that together we’re stronger. Together, there’s a way to bring about change.”

And he’s equally clear about why he refuses to stay silent: “A lot of my life I’ve spent trying to come to terms with my own truth. There are a lot of people not saying anything. History remembers, and I want it to remember me as someone who, in the moments that were super difficult, was saying something and standing up for those who didn’t have a voice. If I have mine and my freedom, I want to free other people as well.”

Do you hear the sound of a bell?

Did you wish your family well

Times ain’t the same in the neighbourhood

Got the parents all going through hell

Cause the guns keep flying off the self

Do you see the man on the street?

Just fighting for a meal to eat

You can write him off as a lunatic

But it could’ve been you or me

If we didn’t ever find our feet

That ethos shapes the song’s tone: Direct, unflinching, but never dehumanizing. “The awkwardness can be taken away if you can see things and speak about them in a way that isn’t damning to those who may not see yet, but leaves a door open for them to question what reality and truth are,” Mon explains. It’s such a precise articulation of what makes his protest writing different: He’s not interested in winning. He’s interested in waking people up without throwing them away.

Love me now

Hold me down

And the government’s staying on heavy foot

And they try to keep us all down

No they’re never gonna keep us all down

The song itself holds that tension between care and clarity. “Love me now / Hold me down / And the government’s staying on heavy foot,” he sings, turning intimacy into a political plea, and a political plea into something you can actually feel in your chest. Later, the writing sharpens into a specific kind of cultural critique – not just anger, but awareness: “Do you see the man on the screen? / Just a puppet though you never see the strings / Calling it a war not a genocide.” The point isn’t shock value. The point is sight.

Do you see the man on the screen?

Just a puppet though you never see the strings

Calling it a war not a genocide

Telling us “It isn’t what it seems”

Man, that’s a different kind of greed

Mon has also framed “Heavy Foot” as both indictment and invitation. “‘Heavy Foot’ lays bare the scars of a broken system, all under the weight of a heavy-footed government,” he explains. “Yet, through this gravity, it sings of unbreakable unity—reminding us that in the face of oppression, our love and solidarity can defy the forces that try to hold us down.” That last phrase matters – love and solidarity as defiance. In Mon Rovîa’s world, care is not passive. Care is an action.

Love me now

Hold me down

And the government’s staying on heavy foot

And they try to keep us all down

Love me now

Hold me down

And the government’s staying on heavy foot

And they try to keep us all down

No they’re never gonna keep us all down

The deeper you get into Bloodline, the more you realize how consistent his moral universe is.

Even the songs that aren’t “political” in a headline sense still carry the same values: Attention, empathy, responsibility, truth. “Living life comes with a responsibility – to care for those around you, and to pay attention to the world that can be so fleeting,” he reflects. “If I’ve done that for some people, that makes me super happy.” That’s the album’s quiet mission statement, written not as branding, but as belief.

What’s remarkable is how the album can carry all of this – protest, memory, identity, labor, lineage – without ever feeling like a lecture. Mon’s writing is warm. He doesn’t stand above the listener; he stands with them. Even when he’s challenging you, the tone is still human.

That sense of shared humanity becomes especially clear in the album’s closing stretch, where the music begins to feel like an exhale – not because the world has gotten easier, but because the album has made space for hope to exist without naïveté. The final track, “Where the mountain meets the sea,” lands like a gentle dreamscape, a closing hand on the shoulder. “Let me take you to a place only I know, I try to capture the lightning in a bottle, hourglass falls in a way that moves time slow,” he sings, letting the song drift toward something like peace. “Sands in the canyon of Topanga, roads wind but lead me right to ya, lay down my arms to bare my soul.” It doesn’t erase the heaviness that came before it. It simply refuses to let heaviness have the last word.

That’s the larger emotional architecture of Bloodline: It refuses to let suffering be the end. It’s the same promise Mon makes explicitly – “life does not have to end with suffering” – now rendered across sixteen songs, each one a different way of saying: You are still here, and that means the story is still unfolding.

Let me take you to a place only I know

I try to capture the lightning in a bottle

Hourglass falls in a way that moves time slow

Sands in the canyon of Topanga

Roads wind but lead me right to ya

Lay down my arms to bare my soul

In the end, Bloodline is powerful not just because it’s beautiful, but because it’s purposeful.

Mon Rovîa is writing and singing from a place of lived experience and hard-won clarity, and he’s doing it with a rare kind of tenderness – the kind that doesn’t just comfort, but calls you back to yourself. These songs are memoir, yes, but they’re also invitation: To remember, to pay attention, to take responsibility for each other, to speak up, to care for one another, to hope.

And if Bloodline truly becomes what Mon asked it to become – “a companion” – it will be because it does what the best records do: It meets you where you are, tells the truth without flinching, and still leaves the door open for light to come in.

— —

:: read more about Mon Rovîa here ::

:: stream/purchase Bloodline here ::

:: connect with Mon Rovîa here ::

— —

Stream: “Heavy Foot” – Mon Rovîa

— — — —

Connect to Mon Rovîa on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Carter Howe

Bloodline

an album by Mon Rovîa

© Carter Howe

© Carter Howe