Alex Ebert (of Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeros and Ima Robot) lets go of expectations and embraces freedom on his second solo album ‘I vs I’, a bold and emotionally charged musical affair.

Stream: ‘I vs I’ – Alex Ebert

Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeros. Ima Robot. Alexander. These band names each evoke different styles of music, but they all ultimately derive from the same creative genius: The one and only Alex Ebert. A singular musical figure (and Golden Globe winner) with an impressive, if not sometimes surprisingly expansive resume that already spans two decades in the public eye, Alex Ebert is a free spirit full of limitless ambition and creativity. Ebert’s new solo album I vs I exemplifies his admirably uninhibited approach toward artistic freedom – yet in order to understand what makes this album so special, one must first understand where it comes from: Alex Ebert’s own journey to the present.

In the midst of finding what most would call “underground and major label success” through his punk/art rock outfit Ima Robot in the early 2000s, Ebert started a new group: Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeros, a folk rock “collective” intended as a means of communal sharing and personal cleansing.

“Edward Sharpe started off as this idea that I wanted to really bring this immense freeform harmony to the people,” Ebert explains. Inspired by his elementary school music class – where everyone was “banging on stuff and everyone was playing and it was a big old fancy mess” – Ebert envisioned his new group as a way to connect back to what he valued most. “Totally outside of the box, I never wanted to play an actual club, I never wanted to play an actual festival; I wanted to play parks and parking lots and houses, and just bring this fucking movement of un-professionalizing professionalism, getting back to the real root of why we all love music.”

A sea change from Ima Robot, Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeros went on to enjoy tremendous acclaim and critical success, releasing four albums over the span of a decade and garnering attention with songs like “Home,” “Man on Fire,” “40 Day Dream,” and more. While Ima Robot ultimately faded during this tenure, Ebert also found time to write and release a solo album in 2011, and he began to venture into film scoring; his soundtrack for Robert Redford’s film All Is Lost won the Golden Globe for Best Score in 2014.

Meanwhile, Edward Sharpe toured the country whilst remaining true to its communal roots, sometimes consisting of as many as twelve members at once – but by the time 2016’s PersonA released, Ebert had yet again grown sour of his situation.

“Eight years down the road, and we’re in a fancy bus now… we’re staying in hotels and we’re going from one gig to another and we’re concerned about how much we’re getting paid. We lost the fucking plot, you know? To me, we lost the plot.”

“And I know that the “loss of plot” was actually the end game – like, it’s what everyone wishes they could do, which is earn a living from being a musician and just do this thing – but for me, that wasn’t the point, so I got really disillusioned and didn’t know what else to do, but just stopped touring.”

A few years, a baby, a breakup, and some music in-between brings us to 2020 and Alex Ebert’s second solo release, I vs I. The first in what could become a long-running series of musical releases finds Ebert relying on instinct, rather than branding – making the music he wants to create, when and how he wants to create it. Some might call it experimentation, but for Ebert, everything he makes is just a part of his overall vessel for self-expression. I vs I is, as a direct result, rather abstract in form, yet grounded in substance; the work of a musical maverick forever chasing that blank canvas, always making his next debut.

“This whole process for me has been about coming back to myself, so this is probably the least spiritual album, and the most worldly and personal album,” Ebert reflects. “The most in-my-emotions, emo, self-centered album that I’ve probably ever made, but it’s been part of my process to get back to myself.”

I vs I is exciting, distinctive, and unique. If you approach it with any preconceptions, you’re listening to it the wrong way. It is wholly unlike anything from Alex Ebert’s catalog, and that’s the way he wants it to be. Songs like (Atwood Editor’s Pick) “Stronger,” “Her Love,” and “Miracle” highlight the artist’s strong falsetto voice and his ability to excel within pop structures, whereas tracks like “Automatic Youth” and “Hands Up” introduce new sides to Ebert’s artistry, such as a long-dormant penchant for rap and hip-hop.

“My life, from age seven on, was just all hip-hop, and so all the early Ima Robot stuff was all hip-hip… it was all beats and rapping and whatever.”

In the spirit of letting go and being unapologetically true, Alex Ebert’s new album is the most himself that he’s ever been.

“Instead of sort of running from that, I decided to just embrace it. So I guess for me what this album really represents is, ironically, in some ways, the courage to not just be communally hopeful and communally personal, but to be emotional – just to talk about the fact that my baby mama left me, and that it fucking hurts.”

Time will tell if Alex Ebert’s latest venture mimics the success of Ima Robot and Edward Sharpe, but like those two projects at their starts, that isn’t the point. Ebert’s music is a vessel of unbounded, untethered musical expression from one of the few high-visibility creators who has stripped himself bare of all pretense. What Ebert is doing is bold, daring, and praiseworthy – not only for his own story, but because his actions are genuinely inspiring; they provide a framework for other artists to follow their instincts and be true to themselves as well.

In an increasingly homogenous musical landscape, Alex Ebert proudly and defiantly the stands out.

I wish I could be as real and authentic in my normal life, as I am onstage.

Stream: ‘I vs I’ – Alex Ebert

A CONVERSATION WITH ALEX EBERT

Atwood Magazine: Alright, so, Alex Ebert! I did a little bit of homework, and I'd like to start off talking about the maxim that sounds like it's driving your current state of mind: “To all thine selves, be true.”

Alex Ebert: (laughs)

It's in the bio, what can I do? Can you tell me about how this relates to you and your music?

Ebert: Yeah, it’s important to me. It’s sort of like taking the Achilles heel and making armor out of it. I was often really confused by the derision engendered by my attempts to follow my muse, and play whatever kind of music I wanted to, and make whatever kind of art, whenever I wanted to, and put albums together that weren’t necessarily homogenous songs… For me that was really sort of natural, but it incurred such criticism. And I was always trying to understand that divide between my own natural muses – my multiple muses – and how that fit into the to the notion of “branding.” And more and more, it really became branding: At first I was thinking about how it fit into “goodness” or “compelling content,” but then I started to realize that the multiple selves thing wasn’t taking away necessarily from the quality of my creation, but taking away (I understood it more and more) from the consistency of branding.

That at first concerned me, to a degree, because it concerned other people so much. I was really trying to understand how to parse that – is it that I’m going through my blue period like Picasso, or going through my Cubist period? And within each period, am I allowed to change, but within each period I have to sort of remain the same until I leap to another period – that I can’t just sort of do things? I think the thing that really started cracking this open for me – because even with Edward Sharpe, I felt like moving from Ima Robot to Edward Sharpe, I felt that concern (and I got fairly lambasted for going from a perceived punk rock sort of thing, to a perceived hippie thing; it was like, “Well, clearly, we can’t trust this person.”) Then I got this gig scoring a movie for All Is Lost, and it was classical music, and suddenly, for some reason, that gave me permission. Scoring a movie, you really have to be of service: It’s not about you and your own identity – it’s about the film’s identity. I got to herald in the angels of my grandfather (my grandfather’s an opera director), and got to bring that in. My first idol ever was Pavarotti. I had a little statue of him when I was a kid in my room and it was like my favorite dude. It never occurred to me that I was going to necessarily make anything remotely non-backbeat based. But then I did that, and I started to realize that all avenues are good avenues; all places that the Muse leaves you are good places. Slowly I started to think about embracing whatever happens; embracing inspiration, basically. While I totally admire and respect artists that tend to always sing the same and produce relatively identifiable music – Paul Simon comes to mind; Bob Dylan, even Bowie in some regard – there’s something for me that I don’t actually identify with. I respect and love it, but I don’t necessarily identify with it as an artist. I always presumed that that was a weakness of mine, but then I started to understand that it was only a weakness in the context of branding and essentially, capitalism. Once I really understood that, and accepted that it was just within that context that it was a weakness, I suddenly was able to perceive it as a strength, and then I could own it. So that’s what it means to me, is the permission I’ve granted myself to allow myself to actually be inspired by my instincts, as opposed to try and curb them or shoot them into the box.

Creating without boundaries. Thank you for bringing me through that. It's interesting; I’m speaking to you here today not because I know you as Edward Sharpe or Ima Robot, but because of Alex Ebert. I think there's something to be said about your singular talent, that each of these projects, though sonically or stylistically distinct from each other, still get picked up and they still get attention. It doesn't seem like there's any one thing that people are gravitating toward, so you must be doing something right.

Ebert: (laughs) Yeah, that would give me strength! That gives me confidence. It’s not a grievance; it gives me strength because it gives me courage to make the next leap, because I have to start presuming (eventually) that there is something that I’m doing right. You can presume possibly that if you hit upon a brand that works, and you keep iterating on that success, you’re fairly confident as to why something will continue to be successful: It’s because you hit on this one particular brand and thing, and you keep making revisions of that success, which is basically the premise of evolution and certainly the premise of capital product – just slightly modifying successes –

It’s the label saying, “Give us another ‘Home.’”

Ebert: Yeah, “Give us another ‘Home.’” And so you sort of understand what that is, but I think that that gives a certain creative precariousness, because you start to doubt, possibly, that if you deviated from that form, would it be successful?! And yet, being able to deviate and then have some success in your deviation starts to make you feel like, “Oh, maybe there’s something more intrinsic to my creativity that is actually creating success,” as opposed to something intrinsic to a particular brand, but something more about me and about what I’m creating. And so I love that, and it gives me a certain amount of confidence to be able to take leaps, and just do the next thing and throw caution to the wind. It’s nice; it’s challenging, but it’s cool.

I admire that; it's pretty cool to speak to somebody who just kind of gives no shits -

Ebert: (laughs) I had to learn to give no shits!

- I understand, but it's admirable and something I think a lot of artists should take from, and I hope they do.

Ebert: Thanks.

I actually saw Edward Sharpe perform in Boston some years back, and I remember you coming onstage in a straitjacket. This question has burned a hole in my mind for many years. Where's the line for you between the performance, and the authentic self?

Ebert: That’s a great, great, great – that’s my favorite question, and the reason that’s my favorite question is because, in my opinion, regardless – in the world of performance, especially – the only general necessity is… how do you say this? In some ways, truth: Some form of truth has to be oozing out of the performer. Now you can be an actor – it could be Brando playing in The Godfather; he’s not actually a godfather, he’s not actually got puffy cheeks – he’s got cotton in his mouth – but he’s oozing some kind of truth. And why is that? And why is it that that’s a great performance, and then a not so great performance isn’t oozing that thing, and yet it’s the same concept – you’re trying to play the same character, but one actor is really making you feel it and the other actor isn’t. Is it because the other actor is acting better, or is it because there’s something else going on?

My mother is a stage actress, and she teaches at the actor’s studio actually – she teaches “the method.” When I was a kid, she would bring me to method acting classes, and I would sit in on Al Pacino’s acting coaches – Charlie Lawton, in his class. I’ll never forget the first time I went in: All the actors are there, and they all kind of just started breathing, and they’re like getting really into it, and then they all start moaning, and then they’re all starting to just sort of dance around the room, and then Charlie says, “Did you guys all bring your animals?” and then all of them say, “Yes,” and he goes, “And begin.”

So each person had brought in an animal – one was an elephant, one was a tiger – and they all just start roaring and crawling and screaming and crying and letting go. And what I immediately understood was, this was a relaxation session. The reason you’re having actors pretend to be an animal, and really let it go, is to push against that embarrassment, that social anxiety, essentially to get to a place of relaxation. Why? Because relaxation, just like in meditation or anything else, relaxation is the gateway to truth: T letting the truth flow through you. The instinct taking over – that truth of instinct. And so the reason it’s my favorite question is because it doesn’t matter if I’m onstage with a beard, or a shaved head, if I’m puking, like doing one of my performance art pieces: The only thing that I care about onstage is being relaxed enough to let the electricity of instinct guide me.

Very often I’ll be on stage, and I’ll be in it, I’ll be in it, it will be one instinct to another instinct, and all of a sudden, I’ll do something that’s fraudulent. And I’ll know it because my body freezes up, and suddenly the world isn’t pouring through my synapses. And certainly, I’m doing something because I’m posturing, I’m posing; suddenly I’m afraid – I had an instinct to jump into the crowd and I stopped myself. Why? Because I was afraid it would look stupid. And so suddenly, now, I’m not free. And so what I’ll do is I’ll just stand there and do nothing, and not make the next move and just relax. I’ll keep singing, but I’ll just stand there and wait until I’m relaxed enough that the energy starts to pour through me again, and I allow my instinct to be the trusted shepherd.

I remember some of the first reviews of things – you know like, “He’s acting the part of a this,” or, “He’s doing a thing of the that,” and “He’s playing a role of this.” I think unless you’ve been a performer, sometimes you might not understand that… Like for instance for me, I wish I could be as real and authentic in my normal life, as I am onstage. I wish, I wish that I could be – like, that’s my life goal: Is to try and be as true to myself offstage, as I am on it. I give myself permission onstage – not only do I give myself permission, but everybody else gives me permission to be myself on stage. They give me permission to do whatever I want – to act out; to dance like a crazy person; to scream; to smile; to laugh at silly things. And in life I’m more bound by the social structures. I think that, while I may show up onstage looking a certain way or doing a thing or doing something else, the common thread is, the only way it’s a good performance is if I’m being true to the moment. And I guess for whatever reason, I decided that day that I needed to wear a straitjacket and express something that… Or maybe it was just a silly idea, an instinct I had to do that… I vaguely do remember that! That was a one-off thing; it was like this weird thing that had all these places to hinge things up, yeah…

The only thing that I care about onstage is being relaxed enough to let the electricity of instinct guide me.

You are fascinating. It sounds like the line between performance and authenticity is fluid for you, or at least you are attempting fluidity every night you're onstage.

Ebert: Yeah, exactly. I’m attempting fluidity in life. I can be an uptight, socially anxious misanthrope in life, but when I go onstage I have to let all that go. Sometimes I’ll try and do something like get really stoned before going onstage, not to relax myself, but rather because getting stoned makes me so anxious, and it will make me so anxious and the anxiety so overwhelming, that I’ll have no choice but to let it go. It’s like, I cannot function onstage this anxious, so I have no choice but to try to do one of those exercises and let it go. I don’t know; it’s interesting.

You've talked previously about how Edward Sharpe “both is and isn’t a character” – that he's the parts of you that need to be cleansed, in some way. Are we at the point now where the cleansing has been completed and you’re free to make music as Alex Ebert?

Ebert: (laughs) I love that! Well, I’ll get personal for a second. I’m in a stage of personal cleansing, yeah. I don’t think that we’re at that point where I’m cleansed, but I’m coming back to myself.

I’ve gone through a period of immense disillusionment, and I think grief, over the last three or four years – breaking up with my baby mama, and that immense dream of our family dissipating, and then the repetition of the cycle of album and touring… Edward Sharpe started off as this idea that I wanted to really bring this immense sort of freeform harmony to the people totally outside of the box. I never wanted to play an actual club; I never wanted to play an actual festival; I wanted to play parks and parking lots and houses, and just bring this fucking movement of un-professionalizing professionalism, getting back to the real root of why we all love music: Not the product. The main inspiration for Edward Sharpe was my elementary school music class, where everyone was banging on stuff and everyone was playing, and it was a big old fancy mess. That’s what I wanted to bring, and then eight years down the road, and we’re in a fancy bus now: We didn’t end up keeping my Jalopy bus that I bought, and we’re staying in hotels and going from one gig to another, and we’re concerned about how much we’re getting paid. It’s all of this stuff and all of a sudden it was just like, we lost the fucking plot. To me, we lost the plot. I know that’s sort of, to me the loss of plot was actually the end game – like, it’s what everyone wishes they could do, which is earn a living from being a musician and just do this thing… But for me, that wasn’t the point, you know?

So I got really sort of disillusioned and didn’t know what else to do, but just stop touring. This whole process for me has been about coming back to myself, so this is probably the least spiritual album, the most worldly and personal album… The most sort in-my-emotions, emo, self-centered album that I’ve probably ever made, but it’s been part of my process to get back to myself. Most recently, in the last month or so, finally all that stuff is breaking down and I’m finally sobbing about my relationship with my father, which I’ve never done; I’ve only ever joked about it. I’m finally digging through all of this grief. The short answer is yes, I think I’m slowly getting back to it, but I wouldn’t say that this album represents the return to myself. I think this album represents “Step A” in the process of the return to myself.

Edward Sharpe started off as this idea that I wanted to really bring this immense sort of freeform harmony to the people totally outside of the box.

I was trying to line up timelines between Ima Robot and Edward Sharpe and see where one band stopped and the other one began, and how these different phases come together, and how everything fits. As we're talking, I'm coming to realize that nothing fits, and there's so much more to it than timelines and dates and numbers.

Ebert: Well, for instance the Alexander album, I made and finished while on tour. I was dragging around a suitcase of stuff with me, and that was part of what led to my collapse, in a way; I just didn’t stop! It was like a whirlwind of infinite work. It was sort of like all one big mush, and the thing for Ima Robot was really interesting for me, because it was like, do I drag Ima Robot into this sort of new fucking New Age zone that I’m entering, and molest the premise of Ima Robot for the sake of where I happen to be at, or do I let Ima Robot stay expressed as is? It was a really interesting, confusing question. I have the same questions with Edward Sharpe right now. While I was feeling in this really sort of worldly emo zone, where I needed to return to the music of my youth, do I drag Edward Sharpe into that? Or do I just sort of embark on my thing? Because really, this was a personal moment for me.

It’s all sort of tangled up together. Timmy and I, from Ima Robot, and Jim, Jay, Justin and Philip, we’re always talking about, “When do we get back together?” They always want to start something again; sometimes it’s just a matter of time. But yeah, it is pretty fluid, and if I had it my way there wouldn’t be any phases really. If I had eight arms, I would just be doing it all at once.

I believe you. Ima Robot is like a cult classic: Do you reboot it and make another series, or do you let it stay and be what it was? Do we bring back The Office, or do we just let it be because it’s part of its time?

Ebert: [laughs] Yeah, exactly! I know, I know – it’s such an interesting question.

Jim, Jay, and Timmy have really lobbied for bringing it back, but I have the same quandary. It’s like, when Curb Your Enthusiasm came back I was really nervous as hell. It’s nerve wracking when that happens. I know that for Ima Robot, to do that, I would have to be charged in a similar way – because that energy was really distinct. It’s a good question!

It sounds like for Edward Sharpe, it might be a little different, just because of the way the band was going with personA, and how you were attempting to “stop”, in a sense, being the main focus, and really come back to that “everyone is a part of this” mentality. I want to move on and talk about you and I vs. I. What does this album represent you?

Ebert: So, in a lot of ways, the way Edward Sharpe was a return to my early childhood experience with music in the very basic idea of music and the idea of just banging on a tambourine and singing in unison, completely sans-irony, in a similar way, for me it’s a return to a very specific era – and that is the age of 19, right as I was in the middle of a dilemma as to whether I was going to become a yogi, or a heroin addict. I remember listening to Alan Watts, deciding, Okay I’m either going to start meditating and literally joined an ashram and just do that, and that’s going to be my thing, or I’m going to be a junkie, and that’s going to be my thing, slated on manufacturing hardship.

I decided to go with the “junkie thing” and making music and living in an art space with no AC and no key and just painting all day and making music, and really being completely unhinged in that sense. I have a daughter now, so I can’t choose that, but I felt like I was in a similar position. What I remember most about that era was how native the music I was making back then was to me. I didn’t know Guns N’ Roses; I only knew The Far Side – I only knew hip-hop. I did not understand rock and roll at all, and all my life from age seven on was all hip-hop, and so all the early Ima Robot stuff, which actually I’m going to put out soon, was all hip-hop! It was all beats and rapping and whatever. And I just was at this place where I needed to return to a free, blank canvas, and I had this choice before me, which was either to try and keep perpetuating this brand of Edward Sharpe, or to experience again… I felt really alone; I was in my emotions, and instead of running from that, I decided to just embrace it.

So I guess for me what this album really represents is, ironically, in some ways, the courage to not just be communally hopeful and communally personal, but to be emotional – to talk about the fact that my baby mama left me, and that it fucking hurts. And to be able to talk about my kid asking me if she’s gonna die, just like I asked my dad; and to be able to talk about all of these basic, mundane, personal pains. They’re things that I was really avoiding for a long time talking about publicly. For a long time I almost looked down on them – I kept them away from myself – so I think to me, this is a return to myself: Me in a bubble. I think that it was time to re-incubate, and so that’s what it is.

To me this album isn’t some seminal statement; what it is for me is a return to creativity. I wanted to just be me in a room, making shit up, having fun, expressing myself, not thinking about is this going to be something that the band would like; is this going to be something that my fans would like – in fact, thank you. I haven’t spoken to anyone really about this album, so this is really helpful.

I think what this album actually is… It’s actually me confirming, for myself and for my own benefit, that I am free of the expectations; that I have given myself permission to follow whatever muse – because putting out a full-blown rap song is theoretically a career killer, and that’s what I want. That’s what I fucking want – I need to know that I can do that, and that I’m not afraid of that. I just need the canvas to be blank at all times. I need my muse to have full permission. I think that that’s in a lot of ways what this sort of is, is step one of some kind of initiation for me.

To me this album isn’t some seminal statement; what it is for me is a return to creativity.

This review should just be an essay that you write and title. First of all, thank you so much for being so open and honest with me; I appreciate it. Are you always this perspective and philosophical?

Ebert: Unfortunately, I think yes. (laughs)

I think that's a good thing! I have to imagine that it's a little easier to make a project with a band, than as an individual. With a band, you practice and you rehearse, you write the songs together, and you know (vaguely) the end goal. How do you know the end goal when it's just you, solo?

Ebert: I don’t think you do. And I think that’s sort of the beauty of it. I think what I’ve been working on extricating myself from is the idea of an end goal. My end goal is to put out a lot of music: That’s my end goal now, and so I vs I – this is actually part one, and part two will come out in the summer, and perhaps part three and four and five and six. And the next one will be a piano fucking concerto, blah blah blah, and just whatever happens to come! For me, the object now is just to follow my inspiration and to put stuff out. That’s the goal, so when I have 10 songs that kind of all have an affinity for each other and they’re ready to go, or in this case 14 songs, then they’re good to go and I’m going to put them out and then go to the next thing – as opposed to getting into the mode of marketing, touring, the “this is me now” and “you can expect this from me,” brand identity: Really going for sort of an open spigot. That’s the goal: An open spigot!

I think it's nice that you're calling yourself Alex - that you're going by your name.

Ebert: Yeah, that’s been a whole… That’s a whole other conversation.

Well, from my perspective, it makes sense.

Ebert: Okay, good. Yeah, it’s nice to just be, you know, what people call me.

Listen, you have enough of a legacy, I think, that people will find you – but it sounds like you don't care, necessarily, if people find you or not, because that's not the point.

Ebert: Well, I mean I like the idea that there’s a little rabbit hole of discovery and whatnot. I think that that’s cool… You’re right though; it isn’t necessarily the point. It’s only the point in the sense of, I don’t know, livelihood.

True, true. But even the Ima Robot and Edward Sharpe fanbases don’t necessarily overlap.

Ebert: No, they don’t. I mean, they do with a few of them, but no. I was at some sort of intellectual summit and there was a kid who was helping out this Greek economist, and he was a sidekick – really brilliant kid – and he’s like, “What happened?!” “Ima Robot was this amazing anthem of my teenage years, and then you went off and did this Edward Sharpe thing. What the fuck – what happened?!” So like, some people definitely didn’t come along, you know? And that’s fine! They get to have that thing.

You let come what may, and I like that you're doing what you're doing – and there's that freedom that you keep on talking about, in that unencumbered aspect, and that's exciting! It's scary; nobody ever said it didn't have to be scary.

Ebert: Right.

But you're doing it, and that's cool. Someone's got to do it, right? To prove that it's doable.

Ebert: Yeah, exactly.

So, digging into just a couple of these songs… “To the days of pain and hunger, these are the days that make us stronger,” you sing in album opener “To the Days.” “And the world was much too young.” Why do you open with this song?

Ebert: (laughs) Well, so the album – I realized, while putting it together – was bordering on a linear tale of my past four years from sort of Cavalier lover – a sort of nostalgic revelry, which I feel that song somewhat encapsulates. Also, that song refers to the years of inspiration for this album – like, that era of 19 to 21, and those are the days that I’m sort of referring to. But also, that sort of Cavalier, nostalgic revelry of like, “Well, it could have happened but it didn’t,” and, you know, “Here’s to the days and cheers!” – that sort of thing, which has masked so much of my pain throughout my life, and really, really well. It’s the perfect remedy in a lot of ways; it’s sort of the typical poetic remedy for pain, that nostalgia that can contain so much beauty within it, that it’s almost rewarding in and of itself.

But then that gave way to a sort of cavalier attitude, which then ended up contributing to disintegrating my relationship and the family I was building, and my jealousy, which is why I put “Jealous Guy” on the album.

So it goes from “To the Days” to “Jealous Guy,” and then to “Automatic Youth” which actually describes the breakup – ad then I suddenly started realizing, holy shit! This album in a lot of ways is almost like a concept album: It’s just going linearly from one, to the next, to the next, to the next. So, I had a fun time putting it together.

Anyway, part two of why I put that song first is again not a fuck you, but a sundering for me of any pretense of like, “Oh, the first song I really have to draw people in.” Like, it’s got to be something that the Edward Sharpe people might be okay with, and then it starts off with this rather rowdy and raunchy verse in the first verse about sex and sliding down your anus… I was like, “Still that’s the first song, so screw it!” So I think that there’s a number of reasons, but I also found that that song is essentially a medley of two songs. The first song initially was called, “Don’t Mean Anything,” and yet they blended together – so I don’t know; it’s just sort of like following my instinct and then the storyline of the album.

This album encapsulates a juxtaposition between your desire for youthful creative freedom, and the restrictions of parenthood.

Ebert: Mmh, I like that.

Can you talk to me about songs like “Stronger” and “Miracle”?

Ebert: Yeah, well “Miracle,” my kid’s so fucking smart. She’s seven now, her name’s Eartha. She’s asked me about death a bunch, but she’s asking about death in the most interesting ways: Like, “So do mountains die?” you know, “Do buildings die?” And a lot of those lyrics are actually in that song. And then one day more recently, she said, “Papa, why are you always talking about life and death?” And I was like, “Oh my God, will you come in the studio and record that or me?”And she’s like, Okay fine. So, for me, someone who – like, the very opening song from Up From Below, the Edward Sharpe album, is “I was only five when my dad told me I would die.” For me, the day that my father told me I was going to die – the day I learned and confirmed my own mortality – is the day that I became a poet, basically: The day that I was saddled with melancholy. The day that I became an asshole; the day that I suddenly learned the language of self-destruction. It’s the day of my reckoning beginning, and then to have my daughter asking me these things, and having written so much about death – I mean, I’d say probably half my songs from “40 Day Dream” to “Black Water,” almost half the songs on PersonA, talk about death!

I mean, a lot of them talk about sort of the shadow self and this this confrontation… And then suddenly, I have a kid and now I have this chance, because no one really ushered me through that process. So now I have this chance to explain death in a way that I would have wanted it explained to me when I was a kid. And you’re right, there is a balance there that almost forces me to confront my tendency to be more cavalier and irreverent and ironic, with a need to be earnest and gentle, and yet just as truthful. And so that lyrical confrontation and rub between urges to be more sort of unabashedly cavalier/smarty pants/ironic/whatever, and then also the need to be really cogent and tender with a kid, was really challenging in a beautiful way for me – and kind of exactly what I needed. It forced me into the exact space I needed, especially in that song and “Stronger” as well.

I always thought “Stronger” was about a some love interest, but I’m thinking that “Stronger” is possibly an ode to your daughter?

Ebert: You know, initially, I wrote that song a while ago while making the All Is Lost soundtrack score and the second Edward Sharpe album. I actually wrote that song then, and it was initially inspired by Jade in Edward Sharpe! So it was a love interest, that had turned into a friendship, that had become a very difficult and trying friendship – and yet, a rewarding one, because of the difficulties in forcing me into growth, like a lot of difficulties do. And then there’s the analogs in every aspect: I mean, when you work out, the only way muscles grow is when you tear them. From relationships with my daughter to my father to lovers, it’s all in that willingness to grow.

Having listened to the full album now, “Stronger” feels like the most pop-centric track on an otherwise heavily experimental and multimodal album. I use the word experimental to define music that I can't put it into a box, and I've had a lot of trouble putting your music into boxes.

Ebert: I love that. That makes me happy.

It's definitely a testament to this freeform attitude that you took this time around, I can only imagine the way that your creative process works is such that you made a bunch of stuff, and then you pieced together the stuff that seemed to work the best?

Ebert: Yeah, I’m a big fan of making a lot of stuff and then parsing through and seeing what’s happening, and then checking out what’s on the cutting room floor and seeing if those things are still alive.

But you're also a poet. So how much is pre-written, and how much is an impulsive, in-the-moment studio outburst?

Ebert: I would say on this album, most of it was impulsive, in-the-moment studio outbursts. “Stronger” was written all at once, lyric and melody (the sort of the lyrics came first), “To the Days,” the lyrics came first and then basically everything else was an impulsive sort of outburst.

I really like the line, “Automatic youth, my symptomatic haze, I guess I’m just dead that way.” It’s poetic, moving.

Ebert: Thank you. That’s an example of a sort of jumble, of outbursts that create words that sound like words, and you’re like, “Oh that is what I’m saying, I’m saying ‘symptomatic,’ okay,” and then redoing it so that it’s slightly more audible and phonetically correct.

Finding the order in your chaos.

Ebert: Yeah, exactly.

So we don't really have time to talk about all 14 songs and we’re getting to the time to let you go, but what are some of your favorite moments on this album that we perhaps haven't touched on yet?

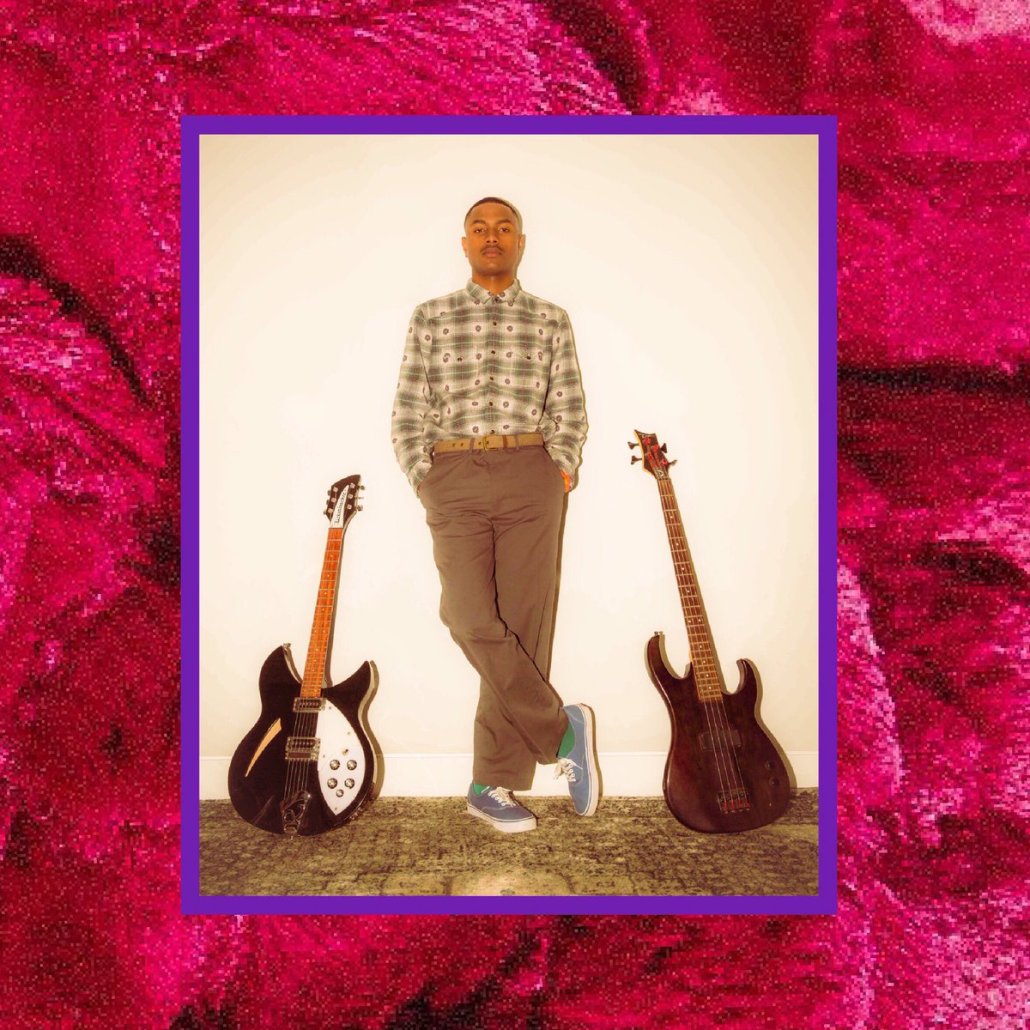

Ebert: I love the bass line on “Her Love.” I had so much fun recording – there’s a local bass player named Donald Ramsey, and in the middle of that song he gets to sort of stretch out, and Brad Walker, the saxophone player, gets to play over it. It’s just this nice, full-on 32 bars of just breakbeat, bass, and sax. I love stuff like that – I loved getting to bring in some of these New Orleans musicians, who are just oozing with talent and soul. That was one of the joys of doing this, is like I did so much of it on my own, but in the cases of when I really needed a great bass line or a saxophone, to have New Orleans at my fingertips was just such a beautiful experience. So, I think in general, the only thing I would add is just that there’s some pretty wonderful musicianship on this thing, particularly from Donald Ramsey and Brad Walker and a couple other folks local in New Orleans.

I think it's really great that you incorporate your surroundings into your music. Even when it’s a solo album it’s not really a solo album.

Ebert: Yeah, I mean the Alexander album was truly – like, I literally played every lick of everything on that album, and it was great. I’m glad I did that, it was good for my growth. But I didn’t need to do that again because I’d already done that, and in the case that you want something “transcendent,” it’s nice to use what’s around you!

I understand that Edward Sharpe’s hiatus is is probably not ending anytime soon, by the sound of it. But that doesn't mean we don't have to see your face in touring spots, does it?

Ebert: (laughs) Actually, I have reached out to the band, and while we’re in the Dominican Republic this February, doing a show, we’re going to start writing! So we’re going to start writing and we’re going to record another album this year. So, yeah – we won’t be playing that much; we’re going to do like 12 shows a year for a little while, and try and put out an album a year for the next three. It’s all part of my desire to have this output – this open spigot thing I was talking about. They’re involved; I want to incorporate them. That’s one of my arms, you know? I gotta keep it moving.

That’s very exciting to hear! Do you ever see yourself performing your solo material as well – these songs that we're hearing on I vs I?

Ebert: Yeah, I will. I’ll be doing Colbert on the 10th of February, and then yeah I will! I just haven’t planned it out yet, but it’s starting to happen. I have to rehearse and figure it out!

— — — —

Connect to Alex Ebert on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Alex Ebert

:: Stream Alex Ebert ::