Following the release of ‘Down in The Weeds, Where The World Once Was’, Bright Eyes chat to Atwood Magazine about the relationship between lyrics and sound as well as forming a connection with listeners.

— —

Since Letting off the Happiness in 1998, the intros of Bright Eyes records have followed a similar ambience: Monologues and soundscapes that are a little weird, slightly psychedelic, and at times unsettling. They set a scene for the proceeding songs in the sense that a narrative is projected and the listener is brought into a world that isn’t just a fixed set of songs played one after another.

LIFTED or The Story Is in the Soil, Keep Your Ear To The Ground begins with a scene between Rilo Kiley’s Jenny Lewis and Blake Sennet as they drive in the snow, the sound of Conor Oberst tuning his guitar layered on top. I’m Wide Awake It’s Morning starts with the infamous narrative about a plane in the process of crashing, Oberst recalling a story about two strangers sat next to each. ‘She says “Where are we going?” and he looks at her and he says/ “We’re going to a party, it, it’s a birthday party/ It’s your birthday party, happy birthday darling/ We love you very, very, very, very, very, very, very much.”’ Cassadaga starts with a woman explaining a journey the protagonist may be going on, while dramatic strings drown her out, and The People’s Key is musings on the history of time by a friend of Oberst’s called Denny Brewer (who has a voice suited for voice overs in documentaries).

That’s always been a goal of ours, to create this other world that the songs fit in and hope that the listeners feel.

While lyrics and emotion are recognized as being at the core of Bright Eyes, delivered in a way suited to solitude with an acoustic guitar, there are multiple layers and strategic approaches to production and instrumentation that intensifies and alters the narrative. Sometimes they can be minor details, like the hammered dulcimer played in “From A Balance Beam”(2005), adding a light springy texture, or orchestral arrangements like those throughout Cassadaga (2007) that adds grandiose and romanticism. It’s the collaborative aspect of Conor Oberst, Mike Mogis, and Nate Walcott that enables this, their individual strengths and visions harmonizing together. Mogis, as multi-instrumentalist and producer, binds the tracks while crafting the finer details and Walcott, a composer, formulates the more theatrical touches while having an attentive ear when it comes to pitch and specific use of chords. Oberst provides the story, lyrics that could be performed stripped back or embellished, while the other two give it a new life.

The latest album, Down In The Weeds, Where The World Once Was (released August 21), takes sonic elements present throughout their past records, which is appropriate given the near ten year gap since the last. Overall there’s a subtle cinematic quality, like the restless, haunting atmosphere of “To Death’s Heart (In Three Parts)” that merges personal tragedy with wider social ones and the emphatic gloom of “Persona Non Grata” instigated by the involvement of bagpipes. In “Stairwell Song,” a soft reflecting of a past relationship, Oberst sings at the end ‘Nothing changed, you just packed your things one day/ Didn’t bother to explain what happened/ You like cinematic endings’ before a classic, romanticized orchestral arrangement fills the rest of the track.

The introduction (“Pageturner’s Rag”) and outro (ending of “Comet Song”) are recordings of close friends and family and the influence of psychedelic mushrooms. In the ending, Obert’s speech and the background noise is choppy and hypnotic, edited in a way that adds a chaotic otherworldliness to the real. It’s a choppiness that makes its way into the transition of other songs, for example at the end of “Hot Car In The Sun” and “Pan and Broom”, therefore keeping the vision in place. While Down In The Weeds… is an album that draws upon ageing and coming to terms with human life, the escapism that balances this is perhaps representative of how it’s the ultimate medium for helping us adjust and understand.

Oberst, as a singer-songwriter, approaches music with a timelessness which is why people have been connecting with his songs since the 1990s. Poetry at the core, the lyrics and the delivery is uncomplicated and emotive. Following the release of Down In The Weeds, Whether The World Once Was, Atwood Magazine spoke to Conor Oberst and Nate Walcott about forming connections through music, the relationship between sound and lyrics, and the process of making this record.

— —

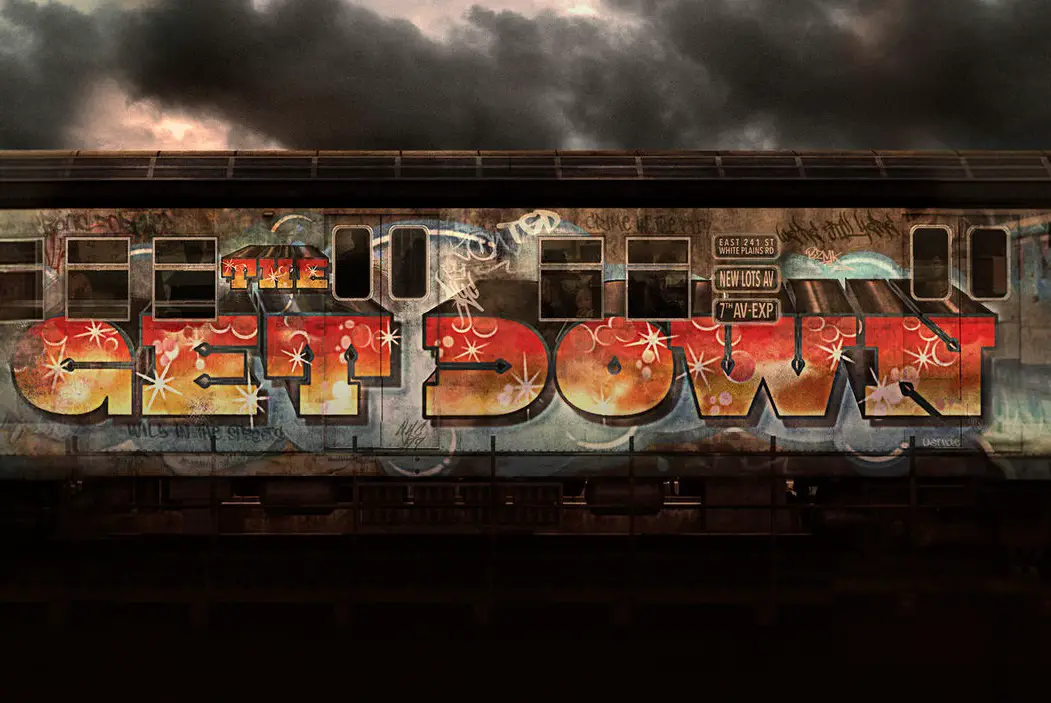

‘Down In The Weeds, Where The World Once Was’ – Bright Eyes

A CONVERSATION WITH BRIGHT EYES

Atwood Magazine: Music has different functions, like favorite artists are favorites to people because they each bring something special. With Bright Eyes, and I feel this is probably why you’ve resonated with so many people for so long, it’s that your songs hit me right in the heart. Like I’ll be listening to a song, whether it’s recent or old, and there will be certain lyrics that just sum up my mood. They’re sad but they’re delivered in a beautifully poetic way that they bring comfort and motivation. Are there any artists that have this same effect on you? That you can listen to and not feel so alone or listen to and feel an instant reaction. And, if so, what is it about the songs?

Conor Oberst: In terms of all time, there’s somebody like Leonard Cohen. I’ve always aspired to write at his level with his use of of language. There’s like the meaning of the words, the literal meaning of the words and the narrative, and then there’s this undercurrent of emotion. There’s subtext in his words that just blows me away.

Are there any songs in particular that stand out for you?

Conor Oberst: Ohhh man. I think some of the ones that are a little more mysterious, like “Avalanche” and “Famous Blue Raincoat”. There’s the narrative but the subtext means there’s more to it than what’s on the page. I think if you’re starting to talk about the way music and melody interact then I think that’s a big difference with songwriting. Or it’s a good example with Leonard Cohen because he’s a poet first. I’ve always thought that music and songwriting are such a different art form to poetry and pose because there are the words on the page but it’s emotionally reinforced by the melody and a line on the page can be kind of simple and straightforward but with the melody and arrangements it takes on this whole new emotional meaning. That’s what makes me really interested in songwriting verses other art forms because there’s like two things happening at once.

I was watching the studio tour that Mike gave on Instagram and I think that he said that he likes instruments that have a human quality and sound like they’re crying. Nate, to what extent does the sound of the songs stem from Conor’s lyrics? Do you and Mike read them and think, ‘Oh, the instruments need to be like this to capture the mood of the words’?

Nate Walcott: The meaning of the song is socially the ultimate goal and we aim to emulate other sonic considerations and elements. We’re not just making them for the sake of liking them, It’s all about the intention of the songs. But how that happens is usually based on intuition. It can be as direct or specific as the cinematic ending on “Stairwell Song” and then the orchestral outro. Or it can be much more vague and based on intuition. There are several songs that involved more of a deliberate contrast. It’s hard to pinpoint but also when you’re working on songs, the lyrics can be kind of in flux. I think this is testament to what a great songwriter Conor is but they’ll always been in tandem. It’s not like he shows up with the lyrics and is like ‘ok this the song we’re going to do.’ In this case, especially on this record, there were a couple of songs where I would bring in a chord progression and he would put lyrics to that. Sometimes it will be a start and then morph and evolve into something else as we work on the music. Sometimes we react to it directly and rear it, sometimes we do the opposite, and sometimes we don’t do anything because the lyrics just come together. It’s a serious process where the ultimate goal is to elevate the intention of the song and to make it as fun and interesting and lovely to listen to as possible.

Did you have a vision in mind before this record started to fully come together?

Nate Walcott: When we were talking about making this record a long time ago, people we were talking to were latching on to this term of phrase ‘apocalyptic sound’ of the album and I was using some of the sounds that may relate to this apocalyptic but in such a different context and way. The choir and the orchestra are beautiful to me and link up with this theme of life. The sound of a thirty piece orchestra playing a melody is a way of saying a lot and a little bit all at once.

Cassadaga is an album when things really started to get more cinematic. Is that kind of the goal, to bring a visual element to the narratives? Because as you’ve said in the past, Conor, the best songs are ones that still have meaning when stripped bare and your songwriting is the same in that you can just read the lyrics and it be like reading a story.

Conor Oberst: Yeah, I think that’s something we’ve always been interested in and attracted to. Not only with the cinematic quality of the songs, what Nate supplies which is composition and orchestral arrangements, but also I think we’ve always just tried to have songs that exist in another space than just a sterile recording studio silence. All the realization of sound and collages and little segues that are a little more freaky with effects and delays are meant to take the listener to a different place and different universe. Not every song is just stop and start, the listener is meant to be transported to this other sort of world for the duration of the album. That’s always been a goal of ours, to create this other world that the songs fit in and hope that the listeners feel.

Nate Walcott: Yeah and I think it’s also important to add that the words cinematic and orchestral are coming out more and more in films which I think is exciting. A lot of people compare this to film scoring but I think, as Conor mentioned, transitions and when sounds are reversed can be just as cinematic in a way as a thirty piece orchestra and I think this is something that all three of us enjoy about that broadness of bringing a cinematic quality to sound.

With Down In The Weeds…., you collaborated with other people like the orchestra and the people that played the bagpipes. What made you decide to branch out in that way for this record?

Conor Oberst: We’re always trying to push ourselves and use different sonic palettes on all the records and try and paint different new colors. The bagpipes was an idea I had based off of that song “Persona Non Grata” which is like a funeral dirge and I associate that with the sound of bagpipes. We’ve never had bagpipes on a record, we’ve used a lot of instruments on the records so it felt fresh and exciting to use a different sound that we handed used. I think it’s us trying to push ourselves to be as creative and free as possible. We’ve all collaborated with a lot of people and I think what sets Bright Eyes records apart or the relationship between the three of us is there’s so much shared history and so much trust and none of us are embarrassed or conscious about bringing up a wild idea and trying it. I think that’s always been our way of working where we pretty much try anything while we’re recording and a lot of the ideas end up on the cutting room floor, some of them work. We usually just record whatever ideas any of us have and a trick when it gets to the mixing stage is that you can’t leave it all in, you’ve got to value space and you still want the lyrics to get to the forefront.

It becomes a challenge to manage whatever it is, sometimes it’s like 100 tracks, a lot of different ideas you have to sort through and to find what to amplify and what to cut out. Mike is a big part of that, he’s just a great mixer and understands what’s impossible sonically and what ears are going to be drawn to. A lot of that is the way you use different instruments. It’s a lot of automation, things get louder and quieter throughout the songs, just trying to get the listener to follow whatever the thing we want them to follow is. Sometimes it’s the words, sometimes it’s a hook on an instrument. So that’s a really big part of the process. It takes a lot of time honestly.

Nate Walcott: A lot of things people ask is ‘what have you learnt in nine of ten years making records?’ and I think that is one of them. We still had a lot of stuff we had to go over with this record but for me one thing that we got gradually more specific about after working on so many records, even with the orchestral stuff, is thinking more about what we’re making live. That made my work more easier and smoother orchestrating with the different minds. In the past it’s been a struggle when having to choose one and narrow it down but Conor is 100% correct. There were few less of the moments of wrestling the questions that we did earlier on. And I think that comes with experience of putting out records.

Conor, you’ve obviously been writing songs for many many years. Has your process changed in any way?

Conor Oberst: Well I think at the core it’s the same process. I would kind of equate songwriting with me as an extension of daydreaming, allowing yourself enough space both physically and mentally to let your mind wander and let that kind of mysterious part of my brain extract that information that sometimes is at the bottom of my brain swirling around for a long time. I’ve always said this where I don’t really write from a state of heightened emotion. If I’m really sad or really distraught about something then I don’t tend to write because I’m just too in my head and depressed to be creative. If I’m really happy then I’m usually enjoying that being with my friends and the people I’m feeling happy with. So I tend to write from very ordinary, in between times.

Subject matter-wise I was first writing songs when I was twelve so my metaphors were like video games or whatever. Now, at forty, the frame of references are from places you’re coming from and imagery and things that employ a different point in your life. I think at the essence of what I do hasn’t really changed. I don’t know if that’s a good or bad thing. I guess I write fewer songs. I wrote fewer songs in my thirties than when I was in my twenties but I don’t know if that’s just a matter of life intervening or maybe being a little more discerning about what I think is good. When I was younger I would do songs really fast and never look back at them.

Yeah, for the latest record, I don’t want to say you’re wiser but it feels more reflective like an older person making sense of things in life. Are there any artists that you admire that you feel are great at capturing this essence of life and if so how do they go about doing it?

Conor Oberst: You mean someone who as they get older finds ways to express that?

Yeah or maybe just capturing life or the concept of aging.

Conor Oberst: Again I think there’s a lot of good examples out there. It’s tricky because I think there’s a way of doing it that doesn’t pull the breaks on being a listener. This is going to sound kind of callous but you know like when a songwriter, and I’ve never had a child but Nate has had one so I can understand the impulse, has a child and you have to have the obligatory I love my child song. It’s coming from like a great place but I think there’s a way to do it that’s a lot less on the nose but just something I relate to on a more artistic or aesthetic level. I’m a big Paul Simon fan and I can follow his songs over the years. I don’t know when I found out but I think he made Graceland when he was like 40 years old and when I was like in my twenties I was like ‘oh shit. I’ve got a lot of time.’ Now I’m out of time.

Nate Walcott: You’ve still got time. Maybe this is the Graceland, I don’t know.

Conor Oberst: But him talking about what his wife was like at that point in a way that felt so not corny or like ‘my travelling companion is nine years old/ He is the child of my first marriage’ A line like that is talking about going on a road trip with his young son but it’s also told you all this other information about how he’s not married to that person anymore but left with all the information in between the lines. A lot of the time he has lines like ‘losing love is like a window through your heart’. It’s like goddamn, ok. There’s so much info there without just hitting you over the head with it. Those are the things I appreciate in writing.

Obviously there’s an election coming up. There’s sometimes the argument as to whether musicians should have a responsibility to speak out about politics and social issues and in my opinion if artists have a valuable opinion then yeah they should use their platform but in general they shouldn’t feel obliged otherwise it can just come across forced or fake. What are your thoughts on this and are there any political songs that you feel are great or artists that incorporate politics but do so in a subtle way?

Conor Oberst: Sure. Obviously there’s been a lot of politics in my music over the years and I’ve been pretty outspoken the whole time about my political feelings and I think it’s up to the individual. I’ve always said just because you’re an artist or a public figure it doesn’t by any means preclude you from being a citizen and every citizen has the right to express their beliefs. Of course we have a bigger platform and bigger megaphone to reach more people and that’s great and I think obviously I would never want anyone, whether they’re a public figure or an actor or athlete or musician, to feel like they could express themselves in the public form because that’s how democracy should work and what’s we need to have a functional society. I would never tell The Chicks to like shut up and sing or tell LeBron James to shut up and shoot the basketball. That’s disgusting to me, that idea. But I also think if you’re not a political person or you don’t feel inclined on a personal level. Some people are a political and don’t wanna do that and on the flip side of the coin I would never think ill of someone if they’re like ‘hey I just wanna sing some love songs’ I feel like it’s a personal choice and I dunno in terms of people doing it now I agree with you that it can be kind of annoying. People write songs just capture a moment or capitalize on something.

In terms of music, even though they haven’t released a record in a long time, there’s somebody like Zack de la Rocha who’s been a very significant activist and always put politics in the forefront with the music he’s made. Someone like Killer Mike, he’s a totally bonafide, significant activist. So there are people out there who live and breathe it and make cool music doing it. I think it’s on like an individual bases.

Nate Walcott: I think it’s interesting to note that not just in arts and music but in everything. Speaking to this moment, there’s a lot of inspiring things. Like what we saw with the NBA recently and it was huge and I think without making a statement about the obligation of other things. It’s incredibly invigorating and inspiring and empowering to people in all industries during a time when we really need it

A great way of broadening musical taste, especially in regards to older music, is through discovering the influences of artists we admire. Conor, you’ve often brought up John Prine in interviews. I’d been aware of him but recently I’ve really got into his stuff but the back catalogue is so big I don’t really know where to begin. Which is your favorite album of his and why?

Conor Oberst: Ohh damn. Well, you’ve got a lot of fun in front of you. One of my all time favorites is called Common Sense. It’s kind of mid 70s. I think if you’re looking at a starting place then the first self-titled one with all the kind of songs you know the best. I like there’s one called The Missing Years which he made with his backup band which is basically like The Heartbreakers. That one’s really fun from the 80s. The one he made after he came back after his first battle with throat cancer it’s called Fair and Square and that one his voice has really changed, it’s way more gravelly. That one’s full of beautiful songs and honestly I really love the last record too, The Tree of Forgiveness, it’s a really beautiful album. But they’re all fun, you’ve got a bunch of good times ahead of you.

Are there any artists that have opened up your mind that you discovered through other musicians that you admire? If so who and how did they have an effect on you?

Conor Oberst: Nate, do you want to take one?

Nate Walcott: Sure. Specifically things that have come to me via friends or other people?

Yeah or maybe just other musicians that you admire. So people you look up to whose influences have then gone on to influence you

Nate Walcott: Right, yeah. I’m finding the most inspiring musician for me right now is a composer and trumpet player named Ambrose Akinmusire. One of my favorite records in terms of orchestral arrangements is Bjork’s Vespertine. The guy who did the orchestral arrangements is incredible. He comes from more a jazz background but he collaborated with Bjork on this record and I’m always coming back to it, including a little bit on this record particularly with the song “One and Done”. Anyway, he put out a solo record and it was jazz but with orchestra and I think halfway through the record I was like ‘damn who is that?” And it turned out who was playing was Ambrose and I’ve since been following his career, not just his trumpet playing but his writing. It’s music speaking to our times but also just very adventurous. Anyway Ambrose Akinmusire put out a record earlier this year and I find the music to be very inspiring and that’s an acute discovery through a different kind of path.

That’s awesome. And finally, you said how with Down in the Weeds... you want to take listeners on a journey like you do with all your other albums. Where do you hope the listeners are transported to when listening to this album?

Conor Oberst: Hmm. I don’t know if I could name it as like a geographical place. I think it’s just creating an alternate mind space with the ideas and the thoughts and the themes and the musical elements. I always think of all that stuff of the kind of the frilly pretentious sound collage intro and all the different strange segues as having the intention of putting the listener under hypnoses or something. You kind of get them in a state where the songs are easier to permeate their psyche and they’re more receptive to what we are trying to say. We’re trying to put them in a headspace where for a lack of a better term they are on our wavelength.

Does that headspace differ much to your other albums?

Conor Oberst: I would say so. I think every one of them is kind of unique to where we were at in our lives and what we were interested in at whatever given time from a musical production standpoint so I think this very much reflects where we’re at the the last couple of years. I don’t think it’s a drastic departure but it’s a different landscape.

— —

Connect to Bright Eyes on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Danny Cohen

:: Stream Bright Eyes ::