It’s a God-awful small affair

To the girl with the mousy hair

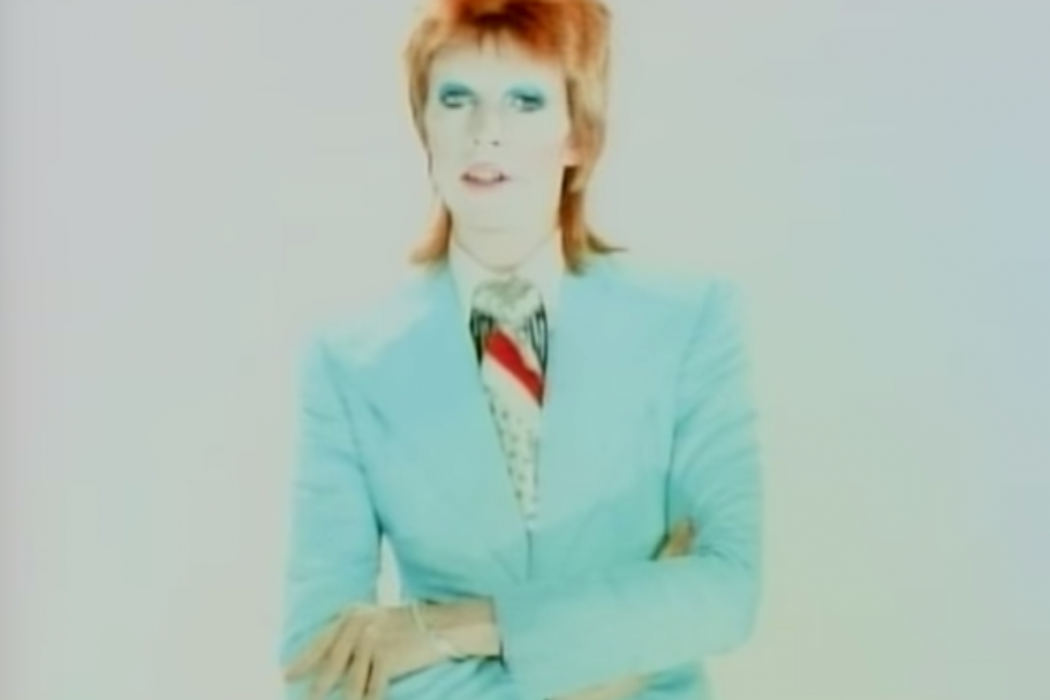

There can be no doubt that David Bowie was one of the most colorful, eccentric and inspired minds to grace the music world. An innovator and pioneer, Bowie has been an inspiration for multiple generations to spread their wings and fly, and there can be no doubt that his mark will be well-remembered in the annals of history. His death marks the tragic loss of a cultural icon, yet it also offers an opportunity to celebrate his life and his oeuvre.

Atwood Magazine has chosen a track review of a favorite Bowie song, “Life on Mars?” as an in memoriam for this great man.

Watch: “Life on Mars?” – David Bowie

To be perfectly honest, I don’t really know why “Life on Mars?” is my favorite David Bowie song. What I do know is that I have always felt a special pull – an attraction, if you will – to this song in particular. Its lyrics are mesmerizing, bringing up many questions and offering surprisingly few answers. Its music is lilting, hypnotizing and almost innocuous.

As I struggle to come to terms with not only his passing, but also the way in which Bowie has influenced me, I hope to gain insight into whatever it is that makes this 45-year-old song so special and timeless.

But her friend is nowhere to be seen

Now she walks through her sunken dream

To the seat with the clearest view

And she’s hooked to the silver screen

Perhaps it’s because of the song’s complexity: Bowie gives us so much to dissect in lyrics that are part-story and part-commentary. The story of the “girl with the mousy hair” is all but lost by the time we reach the second verse, as Bowie attempts to concentrate his lyrics around a crudely-constructed commentary on corruption and history repeating itself.

But the film is a saddening bore

For she’s lived it ten times or more

Perhaps it’s because of the song’s deception: “Life on Mars?” presents itself as an innocent love song, yet it dives deep into the human psyche, pressing us to ponder politics and corruption, perception and reality, conception and existence – “the works,” if you will.

It is far easier to say what “Life on Mars?” is not, rather than what it is: Though it is musically disguised as a ballad, driven by an embellishing piano arrangement with tender orchestral accompaniment, by any measure, “Life on Mars?” is not innocent.

But the film is a saddening bore

For she’s lived it ten times or more

I truly don’t believe that even the late David Bowie himself knew altogether what “Life on Mars?” was about. The song reaches a number of levels and touches on so many abstract, loosely interconnected concepts that, just like any of the great nineteenth century operas, defining “Life on Mars?” by any singular plot line would be doing the song and its creator a significant disservice.

Songs also serve multiple purposes – if they were meant to be essays, then they would be essays! Instead, they exist as much to entertain as they do to offer a point of view. Indeed, some lack the point of view altogether. If anything, “Life on Mars?” offers multiple points of view.

The song does seem to carry one predominant, subtle motif: That of human corruption. Rather than take a top-down approach, I prefer to offer a bottom-up analysis, realizing the song by the sum of its parts, rather than as a whole. Is “Life on Mars?” a quasi-commentary on corruption and the cyclic repetition of mankind’s mistakes? Let’s find out!

She could spit in the eyes of fools

As they ask her to focus on –

Our introduction to “Life on Mars?” comes to us through the eyes of “the girl with the mousy hair,” who experiences some form of abandonment from her parents: A mother yelling “no” and a father telling her to leave can be interpreted as some sort of domestic spat, an estrangement, or other. Nevertheless, she finds herself alone, without a friend, and in her sullen state turns to the television for refuge and escape. The television is described here as “the sea t with the clearest view;” meanwhile, the girl is “hooked” – a reaction to society’s dependence on media, perhaps? – to the “silver screen.”

Crash! Tension enters in the form of orchestral strings that tear into the clean piano. Bowie starts to shift the focus away from the girl and onto the media content, which is described as a reflection of real life: “… the film is a saddening bore, for she’s lived it ten times or more.” What does it mean for the shows to be a direct reflection of life experience? We can learn this from the chorus:

Sailors fighting in the dance hall

Oh man look at those cavemen go

It’s the freakiest show

Take a look at the lawman

Beating up the wrong guy

Oh man wonder if he’ll ever know

He’s in the best selling show

Is there life on Mars?

“The freakiest show” is certainly right. The sailors and cavemen may be separate entities entirely, but it is just as fair to entertain the prospect that they are one and the same: Sailors become cavemen, i.e. they act unintelligent, aggressive, and uncivilized. “The lawman beating up the wrong guy.” Sad to say this seems not to have changed in the past forty-five years; the concept of society losing sight of itself is predominately strong in the chorus’ imagery.

This ultimately leads to the last line:

Is there life on Mars?

Which can easily have two dozen interpretations. Here are a few:

- The narrator, in contempt for the uncivilized, foul state of life on Earth – which we understand to be that way from its reflection on TV – would rather be elsewhere. “Is there life on Mars?” is an honest inquiry into, shall we say, a potential change of address. The narrator would do anything to get off this planet and find another, more hospitable and warm home.

- The question of life on Mars – and moreover, is there life beyond Earth – is certainly one of mankind’s greatest unanswered questions. However, let’s consider the context of the song: “Life on Mars?” was released as a single off David Bowie’s album Hunky Dory in 1971, just two years after the Apollo 11 landing in July 1969. In 2016, the question of life on Mars doesn’t feel all that alien: With multiple rovers there, Mars is no longer as far away as it once was. In 1971, Mars felt light-years away. One can almost hear a motherly scold: Mankind has just reached the moon, and you already want to go to Mars?

- As potent as the question’s context is its contrast within the chorus. The dynamic juxtaposition between the previously-stated societal problems and the ultimate question is so potent that it almost feels ironic. Again, I choose to invoke the motherly scold: All of these problems on Earth, and here you are thinking about Mars?! Why don’t you fix the Earth before venturing off into space?

All three of these interpretations hold weight and need not be entirely separated, but I find myself drawn most to the third point – that society has all these issues, yet we dwell on the least pressing, most abstract one: Life on Mars. Mars is our escape. It is our way of masking the problems that really matter – domestic violence; corruption; endless war. These are the things that affect our daily lives, yet at the end of the day, what does everybody want to know? Bowie even made it the title of his song: Is there life on Mars?

Bowie dives deeper into society’s corruption in his second verse:

It’s on America’s tortured brow

That Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow

Now the workers have struck for fame

‘Cause Lennon’s on sale again

See the mice in their million hordes

From Ibiza to the Norfolk Broads

Rule Britannia is out of bounds

To my mother, my dog, and clowns

This verse reads more like one man’s laundry list of rant topics, rather than the poetic storyline through a young girl’s viewpoint. The dichotomy between the first and second verses speaks much to the Bowie’s frustrations: He has so much to say, but he can only fit that which the stanzas will allow. Hence he creates volatility in the second verse, a move that keeps listeners uncomfortably on their feet. There’s no time to settle back into any normalcy or parallel structures:

It’s on America’s tortured brow

That Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow

- Mickey Mouse has lost his purpose due to capitalism – he exists to make money. “America” is presented here as the ultimate capitalist state.

Now the workers have struck for fame

‘Cause Lennon’s on sale again

See the mice in their million hordes

From Ibiza to the Norfolk Broads

- Here Bowie inserts communist and socialist rhetoric to counterbalance (or perhaps destabilize) the prior capitalism reference. His clever Lennon/Lenin, Beatles/socialism pun serves as a nod to both capitalist consumption (Lennon) and socialist idealism (Lenin).

- The million mice reference further pushes socialist/communist ideas. Giving them homes both in Mediterranean Isle of Ibiza, all the way to Norfolk, in the Northeast of England, adds tension in the form of real places. This is not Mars. This is Earth.

Rule Britannia is out of bounds

To my mother, my dog, and clowns

- “Rule Britannia,” an old British patriotic song, is considered among the most lasting expressions of the conception of Britain and the British Empire. It is itself quite the hypocritical song, celebrating “victory” in the face of the merciless slaughtering of innocent lives. For the song to be “out of bounds,” or banned in any way by the proverbial mother and clowns might be a reference to Britain trying to hide its shameful past, which, to a younger generation, might seem just as inadmissible as the historical events themselves.

But the film is a saddening bore

‘Cause I wrote it ten times or more

It’s about to be writ again

As I ask you to focus on

History repeats itself… And on, into the chorus. I love the fact that Bowie takes ownership here. He would technically have to say “I” – or perhaps “we” – in order to fit the song’s structure, but the personal ownership expressed in “I wrote” serves as a claim to the narrative, and therefore to this world, as seen through Bowie’s eyes.

All beautiful melodies and inspiring music aside, “Life on Mars?” appears to be a turbulent and critical commentary on the state of society. Bowie offers his argument through vivid depictions of seemingly fantastical beings, yet once the song is broken down into its sub-components, everything seems to make relative sense. Humanity has lost its humanness; we no longer care about helping our fellow person in need. Despite the myriad issues facing Bowie’s not-so-distant dystopia, people are focused – hooked, to use Bowie’s language – on the most inconsequential and least-immediate issues of the day. The question, “Is there life on Mars?” feels now like the most offensive things someone could bring up, in light of all these topical issues.

“Life on Mars?” is most certainly David Bowie’s vessel for calling out society’s corruption, but the song is far more organized and focused than I had initially thought. Once you break it down, the song makes terrific sense, but it’s hard to imagine any single mind concocting such a seemingly erratic, yet immensely succinct critique. This is David Bowie’s genius: A small, four-minute example of the great lyrical and musical mastermind. Rest in Peace.