Where most rock n’ rollers of his generation indulge in the false comfort of nostalgia, Peter Frampton has continued to push his art. A chance encounter with the soon-to-be Rock & Roll Hall of Famer solidifies his grace and humility, on and off the stage.

by guest writer Robert J. Binney

“Show Me the Way” (live) – Peter Frampton

Finally! From gazillion-selling headliner to David Bowie’s backup to playing-through-pain elder statesman, Peter Frampton is where he belongs.

His combination of raw musicianship, pop songwriting chops, and teen idol looks may have put him on the map, but his grace and humility – on stage and off – is what a “hall of fame” should represent.

Where most rock n’ rollers of his generation indulge in the false comfort of nostalgia, Frampton has continued to push his art. One experience from a cold night just over a decade ago exemplifies this graciousness.

Horizontal freezing rain pelted Philadelphia’s Tower Theater. The show let out just past 11 PM – minutes shy of the three-hour mark – and trains heading downtown ran every 15 minutes. The Tower is technically in a suburb of Philadelphia, so there’s plenty of parking for the minivans that trek into “the city” and not a lot of foot traffic slushing toward the city-bound platform. Surprisingly, few concertgoers had stayed until the end of the show.

Ten minutes into Frampton’s set, the sold-out house was on its feet, three thousand hips shaking to the call-and-response of “Show Me the Way” and half an hour later, serenading plastic cups of chardonnay and swaying to “Baby I Love Your Way.”

These were the songs of their adolescence, of drinking cans of Schmidt’s down the Shore and playing spin-the-bottle in wood-paneled rec rooms, of a time before being married to the lump in the Eagles jersey next to them. The sounds of the Bicentennial. Now, thirty-some years and some number of kids later, “letting loose” usually meant wives disco-dancing to “Shakedown Street” with their girlfriends at some strip-mall tavern, their date’s gaze flicking between the wall of big screens and the dance floor, turned on by the sight of ankle bracelets pinned under pantyhose.

So getting out was big – this isn’t some shitty DJ at Nardi’s or the Geator with the Heater on car radio – this was the real thing, live on stage.

Ninety minutes in, the crowd roared when the once-golden-maned guitarist sang, “Do you feel like I do?”

Clearly, they did. Then the icon – whose first single climbed the UK charts in 1969 – committed a rookie mistake: He announced he was going to play something new.

There are rules for writing set lists, the biggest being: “Save some hits.” Finish on a crescendo, take a quick break, rebuild. Ratchet tension until you and the audience can both climax in a burst of light, energy, and sound – simultaneously, in four-four time.

Save some hits.

Which Pete announced he had not done.

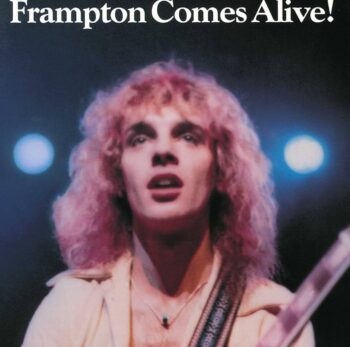

He made it clear at the outset that he was reprising his 1976 blockbuster Frampton Comes Alive! which meant front-loading chart-toppers. And now here he is, introducing a song off his “new CD, which I know you didn’t buy.” Either that was British self-deprecation or a ballsy punk-rock move.

Philadelphia wasn’t buying it. Usually, when a band breaks into a new song, folks take the opportunity for a beer exchange. This wasn’t a handful of people ducking out to piss. This was couples, double-dates, entire rows standing, putting on puffy coats, grabbing bags, and schlepping back across the bridge to Jersey to surprise babysitters and fire up CPAPs. Within a few minutes, easily two-thirds of the crowd had left.

I was gobsmacked – not that people only wanted to hear hits but at the magnitude of the exodus. I felt terrible for the band and got genuinely angry. For his part, Frampton seemed to take it in stride.

During the shared choruses, he hadn’t displayed the manufactured hubris of a casino-headlining reunion band but an almost-humble “Would you believe this shit?” joyfulness. A man who went from working steadily, if anonymously, to being everywhere all at once: Your AM radio, your dad’s car radio, music magazines, teen magazines. In three years he’d gone from opening for the Kinks in a half-house basketball arena to turning the football stadium across its parking lot into Pennsylvania’s third-largest municipality (with Skynyrd and J. Geils in support). And back to three-thousand seat theaters across the river two years later.

Rock shows repackage and reaffirm the familiar, providing comfort in singalongs – although hearing new stuff can be even more entertaining, engaging mind and soul differently. Nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake is less a celebration and reverie, and more unhealthy attachment to personal history. Commemorating is one thing, refusing to move on, another.

I want to say this whole mindset began with TV’s Happy Days, but that’s just my generation’s first taste of nostalgia. Back then, neighbors’ moms swooned to Sinatra’s Capitol records, their grandparents singing in italiano along with Mario Lanza 78s. Hamlet was nostalgic for his days of Yorick; hell, even Lot looked back.

In Philly, people worked where their parents worked, where their nephews and nieces planned to work. Looking backward was safer, because at least they know how that turned out. It can’t disappoint anymore.

There will always be tension between the past and present; we can question providence, accept it, or just ignore it.

With so much out of our personal control, with each day seeming more bleak – we can say things are “never better”, perhaps because they’re always worse – ignorance may truly be bliss.

“Nostalgia” sands the edges off experience and exalts in memories uncovered. A defense mechanism in the face of a terrifying future. There’s no need to be afraid of the past; there may be plenty of regrets, but nothing to fear.

We all reach a point where we have more yesterdays than tomorrows. As comforting as it is to embrace those yesterdays, we can’t change anything about them.

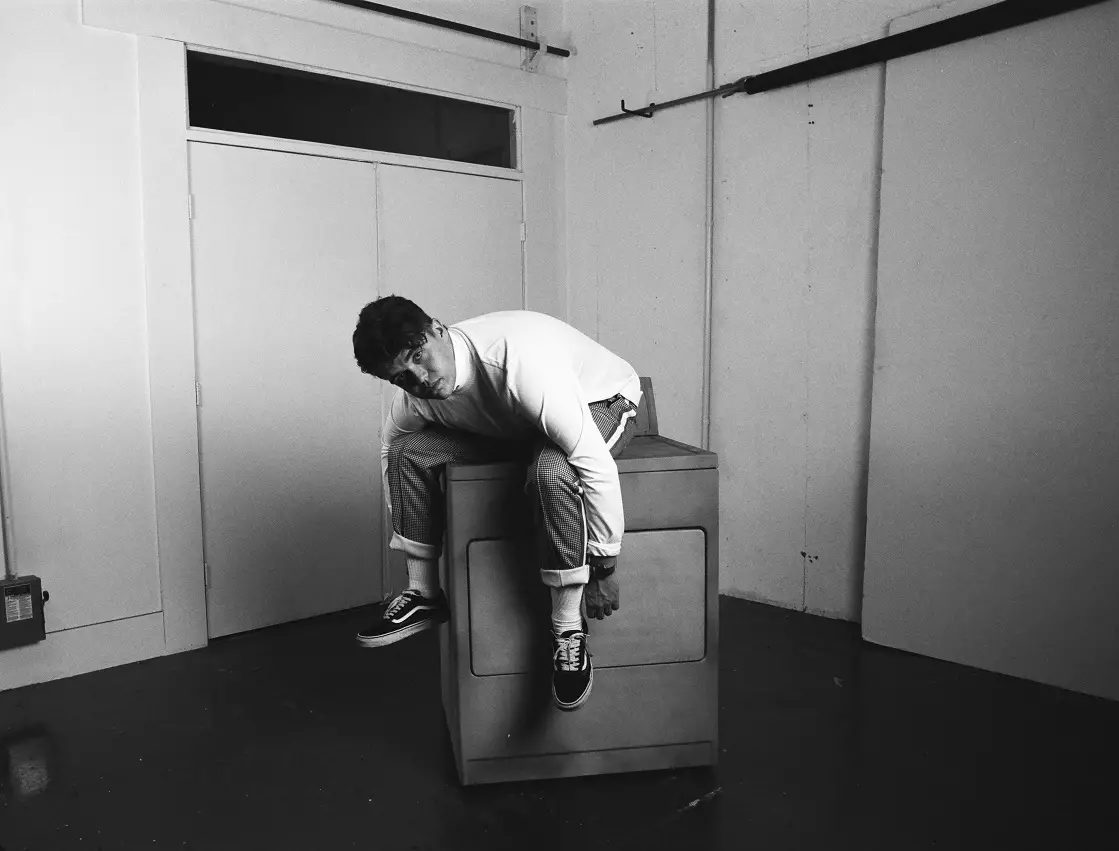

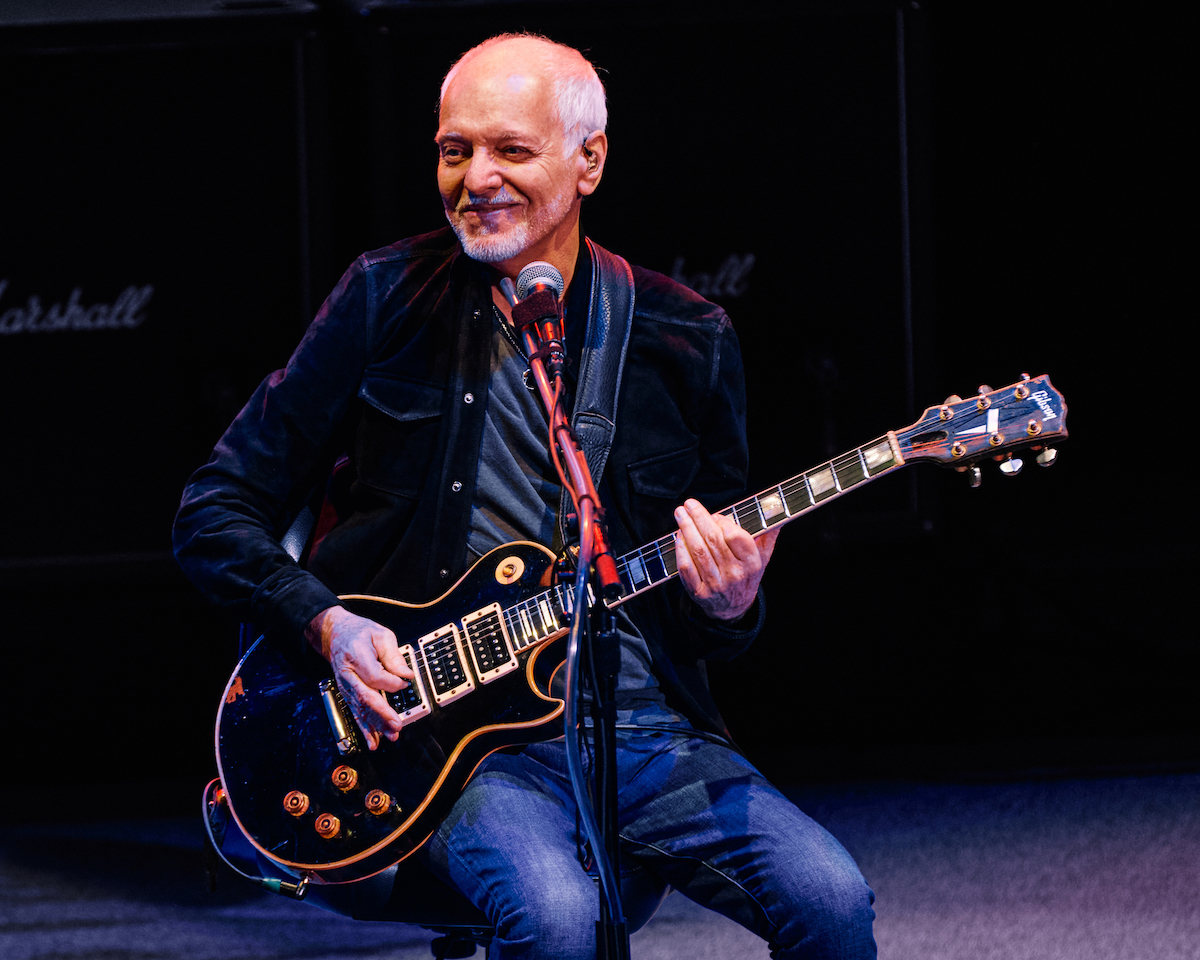

To watch Peter Frampton now, in 2024, is to watch a master burnish his legacy. Don’t be fooled by the cane, by the frail approach to a cushioned chair center stage. The artistry isn’t in the artifice; he isn’t a Madonna pretending to dance or a lip-synching Paul Stanley. Late-career Peter Frampton is Exhibit A that music comes from the soul.

Afflicted with inclusion-body myositis, he can’t bear the weight of his storied guitar, or even bend notes with force. But what he still wrenches out of that instrument – as fierce and melodic and gut-punching as what you first heard on 8-track. This isn’t a past-his-prime quarterback tossing ducks and flinching before a hit; this is a master class in spitting fire and redefining a career of hits.

I didn’t stay at that Philadelphia show out of any moral superiority.

I just wanted to enjoy a night of music, after which I stood at the exit, trying to time my dash through the freezing rain to the train platform.

I hit the crash bar, discovering too late that my way was mostly blocked by an idling bus. Not public transit, but a sleek motor coach. Huddled by the doors, with a desperate look somewhere between hopeful and frostbitten, was a guy clutching his copy of Comes Alive! and another holding, of all things, a tambourine.

Also approaching was local DJ Pierre Robert. If he’s going to stand out here, blowing into his fists for warmth, there must be something happening. I stopped to say “hey” – I’d bumped into him at several shows over the years.

A roadie ambled over from backstage, disregarding the weather in sweatshirt and shorts. His legs looked like Renaissance-fair turkey legs.

The fan protecting his LP under his coat asked, “Is Peter coming out to sign autographs?”

The roadie laughed. “F*** no. You’re crazy if you think he’d come out in this!”

The poor guy with the record shrugged and started to walk away. The roadie moved the barricade, just enough to slide through. But he didn’t, he turned back toward the stage door.

After a few steps, he spun back to us and said, “Well? You coming or not?”

We shot each other a look – a combination of “Who, me?” and “Did he mean what I think he meant?” We shimmied past the barricade and followed his flashlight across the pavement. “Watch out, it’s icy.”

He showed us the way past the brick loading dock and into what could have been the back hallway of any hotel, restaurant, or factory.

About ten seconds later, Peter Frampton appeared. Alone – no security or handlers.

He was a lot smaller than I would have guessed. Just a guy in a leather jacket, not looking forward to braving the cold.

Of course, that was the moment my wife texted: “Where are you?” I replied, honestly, “Standing on the loading dock with Pete.”

“Who?”

Frampton chatted with us, drinking his tea and signing the record and tambourine, discussing tunings and pickups and what years Gretsch made crap guitars.

I said, “You made a crack earlier about folks not buying your new CD.” He nodded and rolled his eyes. What are you gonna do. I held my hands in front of me, a few inches apart, like I was holding a jewel case. “I didn’t buy it either.”

Then I spread my hands about a foot apart. “But I did buy it on record.”

His eyes lit up and he smiled. “I didn’t even know we released it on vinyl!” He excitedly shouted this news down the hall. For a brief second, I was the star.

There’s a wonderful bit in Paperback Writer, a fictionalized biography of the Beatles, where Frampton is tapped to open for the Fab Four’s reunion concerts. In a dark twist, their new music is poorly received, the world moved on, and by tour’s end, Frampton is headlining. Published just weeks before John Lennon’s murder, Mark Shipper’s novel revels in nostalgia for the heady days of Beatlemania, even as it pierces the futility of clinging to the past, of refusing to accept the consequences of time’s eternal march.

Back in the real world, Peter Frampton’s debut album was titled Wind of Change, and even if he will never reprise the sensation he once was, he keeps challenging himself. He won his first Grammy thirty years after his Comes Alive! glory days. And now he’s invited to sit with the giants, in the Hall of Fame, where he belongs.

Being lured by nostalgia’s siren song is easy, both a response to and a preventer of change. I couldn’t articulate it that night, watching the stream of people leaving after dancing to their favorites. But standing backstage, discussing the future, I learned to appreciate the past without dwelling in it.

Peter Frampton’s ongoing journey, his now-Hall of Fame career, reminds us that though there are limited days ahead, each brings the potential for reinvention.

— —

Seattle-based screenwriter Robert J. Binney has written about Joe Strummer, James Bond, joyriding with the Salt Lake City police, and his relationship with President Jimmy Carter (though not all at once) for the Los Angeles Times and other fine publications. Most recently his fiction was published in Down & Out Books’ anthology The Killing Rain.

— —

:: connect with Peter Frampton here ::

“Baby, I Love Your Way” (live) – Peter Frampton

— — — —

Connect to Peter Frampton on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Austin Lord

:: Stream Peter Frampton ::

© Austin Lord

© Austin Lord