Sinkane’s Ahmed Gallab speaks to Atwood Magazine about making his highly ambitious new album ‘We Belong,’ all the practical takeaways from his recent master’s degree program, and how, through community, he learned how to love himself.

Stream: ‘We Belong’ – Sinkane

It’s okay to celebrate yourself and it’s okay to celebrate each other. As Black people we are revolutionaries, we are very strong people, and we can rise above all of this stuff.

* * *

There’s an unmistakeable twinkle in Ahmed Gallab’s eyes as he talks about music.

To the mastermind behind the critically acclaimed, genre-bending project Sinkane, music is everything: His means of self-expression, understanding, and human connection; a vessel for community building; an art form; a science; and more. It’s math – a Sudoku puzzle waiting to be solved – and it’s culture – a means of celebrating who we are, where we come from, and where we’re going.

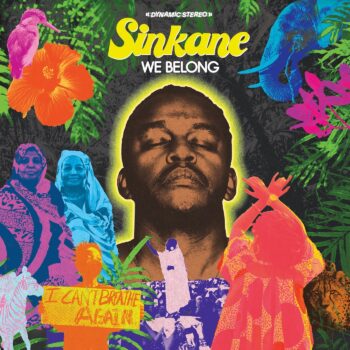

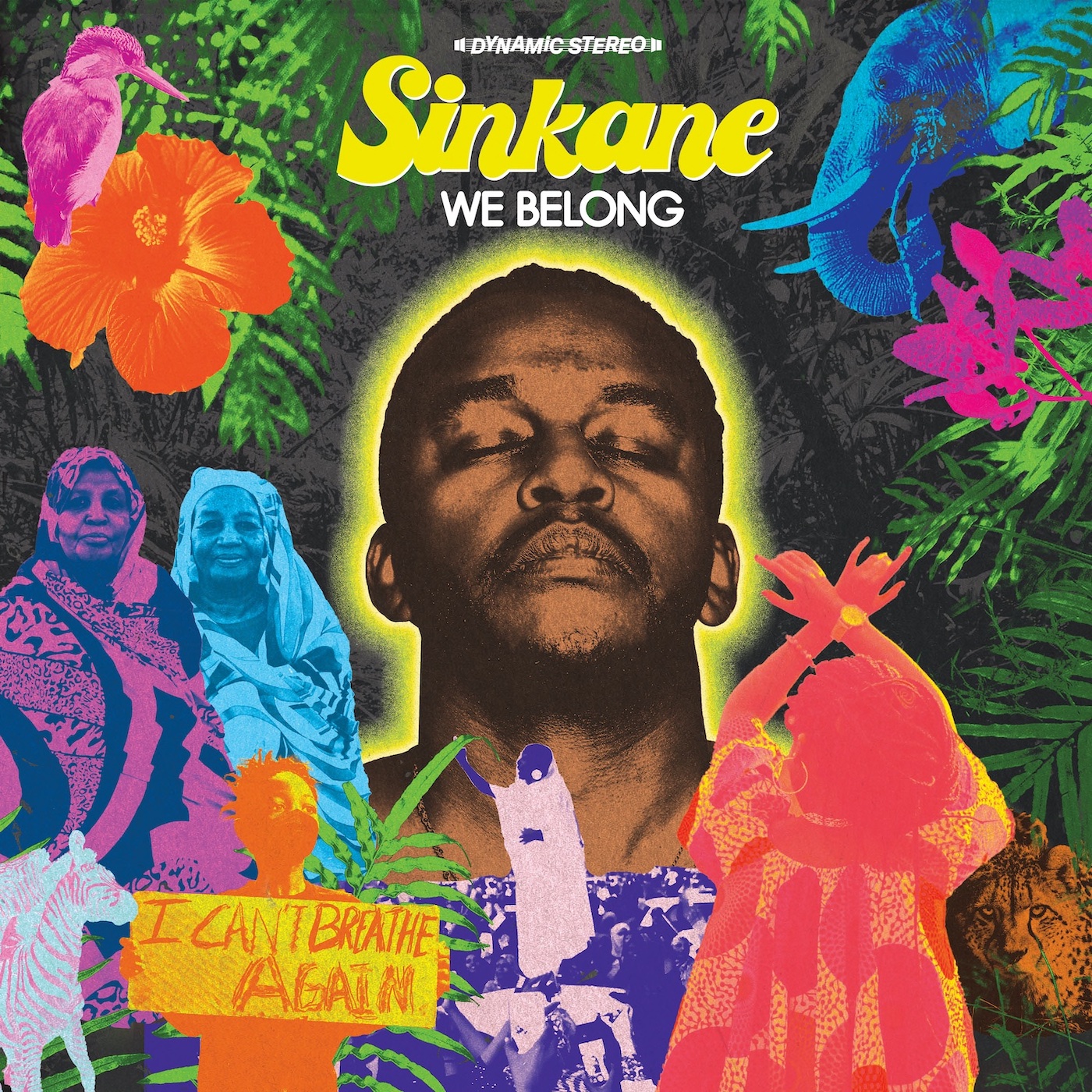

This holds especially true for Gallab’s latest Sinkane record. Far greater than the sum of its parts, We Belong (released April 5 via City Slang Records) is billed as a love letter to the Black experience. Sinkane’s eighth studio album – and first in five years’ time – is the direct result of Gallab intentionally venturing outside of his comfort zone and outside of his wheelhouse. In addition to pursuing (and earning) his Master’s Degree in music composition at SUNY Purchase, he spent recent years immersed in poetry from the Black Arts movement, and engaging with friends new and old in conversation about the Black experience. The result, as the album’s title so perfectly sums up, has been a deeper sense of connection and belonging – to himself, and to his communities – than he ever felt before.

“I learned through community that we are greater than the sum of our parts,” Gallab tells Atwood Magazine. “It was through community that I’ve come to learn how to love myself, and through the collective support in the Black community and actually in the world at large that I’ve come to find my own meaning for belonging as a Black person in the United States and as an African person. When I took myself out of myself and I wanted to work on an album that was not about just me, I was able to find myself in the process… It made me understand my purpose as a producer, as a collaborator, and as a human being.”

“That’s what the love letter to Black music and Black culture and Black people is,” he smiles. “Black people, we thrive in community, especially in the United States, the collective history of African-Americans communities was the only thing that was able to allow for progress and healing.”

“The one thing that this record has that others don’t in my catalog, is that there’s resolve… Through this community, I’ve understood that not only we belong, I belong. I feel my purpose is strong.”

Sinkane’s music has always been multi-dimensional – a melting pot of the modern music canon, merging disparate styles and sounds together under one banner and one home.

A typical Sinkane concert should offer a thorough mix of funk, krautrock, progressive rock, electronica, jazz, and – now, more than ever – gospel, reggae, Afrobeats, and dancehall.

Such musical intersectionality mirrors Gallab’s own intersectionality; he was born in London and raised in Sudan before his family emigrated to the United States. Understanding his own identity, and how he “fit” into the world, has been a salient topic of his music for several years, and ironically it took (literally and metaphorically) getting out of his skin in order for him to finally feel at peace with his own personal “place.”

“Prior to this, I had this internal dilemma with myself about my identity,” he admits. “I’m not African enough when I go to Sudan and people tell me, you left and you got out. Why are you still here? And you don’t look like us, you don’t talk like us. And again, the same thing in the United States. It was a really traumatic and hard thing to deal with, until I finally just dealt with it.”

The product of all this soul-searching, cultural immersion, and more, We Belong answers Gallab’s question: What would it sound like if it was through my lens talking about the collective experience?

“It felt very freeing,” he says of the album’s writing and recording process. “I got really inspired by the music and I felt very connected to it as a Black person.”

A true communal effort, We Belong finds Gallab collaborating with a veritable who’s who of musicians, many of whom he considers close friends, including the late legendary jazz fusion maestro Casey Benjamin, singer/songwriter (and former bandmate) Amanda Khiri, Beastie Boys producer Money Mark, guitarist/producer Mikey Freedom Hart, Phony Ppl’s Aja Grant, percussionist Meia Noite, organist Shedrick Mitchell, and singers Bilal, STOUT, Tru Osborne, and Hollie Cook. In concert, he’ll be performing together with an all-star band called The Message, whose band members include Ronnie Lanzilotta (bass), Dave Palazola (drums), Patt Carr (keys, guitar), Ifedayo (vocalist), and Jessica Harp (vocalist).

“There’s no better high that I’ve ever received than playing Sinkane now with this group of people in these songs. It just doesn’t get old,” Gallab grins. “I would put this band against any band out there right now… I can only hope that people can see it and we get the opportunity to play more and more, because that’s what the point is.”

“That’s the other part of the conversation for Sinkane,” he reflects. “Listening to the record is one thing, but seeing it live is what it’s all about for me. Ultimately, I just want to connect with people. So the more shows we play, the different places that we go, I get so excited about doing that, and I can just only hope that I can continue doing it more and more.”

That twinkle in Gallab’s eyes never faded throughout our hour-long interview as we discussed his own musical and personal growth, his (many) takeaways from music school, and his musical love letter to the Black experience. We Belong is out now: Dive into the wondrous depths of Sinkane’s bold, ambitious, sentimental, and soul-stirring eighth studio album below as he shares stories, unpacks its songs, and explains how a random, mistaken text message from a stranger resulted in a beautiful friendship.

“Now I have this very different understanding of music and I can listen to it in an academic way, but also be creative in learning how to use that inspiration to create what I am making,” Gallab says. “It’s because you can make complicated things feel good, and I think that’s really what it is about our world. We walk out the door every day and we’re dealing with the complexity and we’re dealing with adversity. It really helped tie me into what this record was, and it brought me to jazz and how that’s all jazz is; a reflection of our life as Black people, this intellectual conversation, trying to make these dissonant things work together. And that’s what we do.”

Let’s wake up

Take one breath

And listen for the sound

be in tune, follow your light

be yourself, free your mind

to err is human, to forgive divine

What a time to be alive!

consistently paranoid

Reaching for these false prophets

to numb the pain…

got me in trouble again

Yet I still keep mistakin’ work for love

been down for so long

I keep getting on

same old story

no need to worry

We’re all that we got to hold on

We’re all that we got so be strong

Prevailing till the break of dawn

Because we belong!

Yes, mamma we made it!

Because we belong!

– “We Belong,” Sinkane

— —

:: stream/purchase We Belong here ::

:: connect with Sinkane here ::

Stream: “We Belong” – Sinkane

A CONVERSATION WITH SINKANE

Atwood Magazine: Thanks for your time today, Ahmed! I’d love to begin with the evolution of Sinkane, from a stage name to a band. Can you share a little bit about this change – and is something that you're excited to kind of keep moving forward with?

Ahmed Gallab: I think in my entire career, I’ve wanted this to be the case, you know? I think when I was younger, I felt like I had a lot more to prove to myself that I could do it all myself. The first Sinkane records, I recorded all on my own. I played all the instruments. And I needed that to be clear to everybody, but mainly to myself really. ‘Cause I don’t think anyone really cares whether or not I’m playing all the instruments or I have like 50 people on the record. But I think as long as the songs are good, then everyone is cool. But like for me, I had come out of a lot of collaborative bands and projects and ideas from high school and college, and I always felt like oh man, I have so many ideas of my own.

I just need to do my own thing. And also, a lot of the people that I was inspired to… That had inspired Sinkane were that way. Caribou is that way. And like Cornelius, I remember was a big one when I first started Mice Parade. And spiritualized, like all of these bands, it’s this one central figure, and they pretty much do everything. But I realized very quickly after I’d made one or two records all on my own, that everything sounded better and worked better. And I got to the finish line more successfully and happier if I had worked with people and got people involved and because really, it took me a long time to realize that I thrive in a collaborative experience, and I didn’t know at the time how to be the leader of the collaborative experience and still retain my own autonomy and identity and still have people involved.

And it took a while and it took a lot of mistakes. Like a lot of mistakes. And not knowing how to navigate and bring people in and still make it my own, but I finally did that, you know? And it’s better off for it. It still works around me. I still write all the songs. And I think also just finding the right people, just that we vibe with, being in a band is like being in a relationship with like six or seven people, depending you know how… And a lot of people, it just didn’t work with for one reason or another. But this time around with this group, it’s worked, you know? And everyone’s all in. And everyone’s cool with the way that I’m structuring everything. And again, they’re just bringing the heat. I present something to them, and it’s like all right, you guys definitely know what I want to do here. And you’re showing me some ideas that I could have never come up with on my own. So I’ve learned to trust that. And I just be very clear about everything.

A song like “Another Day” might not have existed without that – you're not even singing the lead. There's a lot of letting go involved in giving somebody else the spotlight like that.

Ahmed Gallab: I’ll tell you straight up, that song, when I first wrote it, it did not sound at all like what it sounds likes now. And I remember Casey Benjamin, Rest in Peace, one of the greatest musicians of all time, we were having a session together, and this is why I loved working with him, was I showed him what I had. I was like yeah, I’m trying to do this like Sly Stone kind of weird psychedelic Sly thing. I was deep in music school, so I had like all of these different parts of the song and I wanted to be like very intellectually interesting and musically obtuse in some way, but like grounded in like a Sly Stone thing. And I remember him looking at it and being like yeah, so let’s work on this.

And I was like, okay. So he obviously is not feeling it. And I was like, “I’m gonna go to the bathroom.” I came back, and he had that synth line. He was like, “I like this. Let’s roll with this.” And then the Bilal part that he sings was a synth line that he wrote, and he’s like this should be a synth line. And I was like man, this is amazing. This is great. And he left, and I wrote the song. I just like mapped it all out. And it would’ve not at all been anything like that had he not come in that day.

So it's like its own chopped and screwed version of a song that you had written?

Ahmed Gallab: Casey was this master of reharmonization and reappropriating ideas. He could take what you were doing and then present you something and to the normal person, it doesn’t sound at all the same. But he’ll say, well, this is what I did. Here’s where I changed what you’re doing, but held the integrity of the melody. And I’m like oh, wow. I just don’t think that way. It’s a skill and is part of his genius, you know? So that happened. And then I sang it initially, but it was so out of… I was so out of my depth singing it. I was like really… My head hurt when I sang it. And I met STOUT and I was like take a stab at this.

And it just came out of her like butter. It was just boom really, really nice. And I think I had… In the studio, that’s where I had this realization where I was like oh this is what I’m meant to do. I can’t do everything. I can’t emote the same way that she does, or true, or I can’t sing like Jessica and Efadayo and I cannot play the bass like Ronnie. But if I present them with something and just kind of let go and let God with these people, it comes through, it rings very, very true.

I know this isn't the first time you worked with other musicians in a recording capacity. Is it the first time you had this familial, collective atmosphere?

Ahmed Gallab: No, no. I think every incarnation of the band had that in some way. But like I said, it came down to me like I would say that. But then when it was time to like come through, it freaked me out. I’d be like oh man, I’m losing a part of myself. You know I’m giving away too much of myself, and then I’ll just like tighten back up and not know how to communicate or not know how to let go, you know? On the last album in ‘Dépaysé’ Johnny Lam and Elenna Canlas, they contributed to songwriting on a couple of the tracks. And the song “Everybody,” the main guitar riff was presented to me by Johnny.

And I wrote a song out of that. So I’ve always wanted to do that. And also, Jaytram, who played with me for a long time, he really had a lot of collaborative and like creative ideas that were used. He wrote the piano line on “How we be” like the song. I didn’t know what was gonna happen with that song. And then I heard that line, I was like let me take it. And he’s like yeah, sure, you can take it. So, I’ve always wanted it, but there was… I’m taking accountability from my end of it, but also this group just gets it in a way that no other group that I played with does before.

You mentioned Dépaysé, and I just want to say “Everyone,” the second track off that record, is one of my all-time favorite songs of yours. There's an energy to it… I just hit the right chord.

Now, this is your first album in five years. It's the longest time you've ever taken in between studio albums. What for you changed between Dépaysé and We Belong? How does this record capture your own life experience from 2019 to 2024?

Ahmed Gallab: Oh, man. I mean, everything happened, everything changed. Well, the pandemic was a huge sigh of relief for me, to be honest, you know?

Really?

Ahmed Gallab: Yeah. ‘Cause up to that point, it was like record for a year, record for a year, record for year, record for year since 2008. I did three Sinkane records before ‘Mars’, and I didn’t really tour on those records because I was touring with Caribou and Montreal and Yeasayer and all those guys. And so I spent four years before ‘Mars’ touring like crazy. And then writing ‘Mars,’ and I got ‘Mars’ out and it was just like one thing after another like that, that record came out. We did what we needed to do, wrote “Mean Love,” “Mean Love” came out, got asked to do the William Onyeabor Atomic Bomb band.

Those things happened at the same time. I did that for a year and a half wrote ‘Life & Livin’ It’ like right away. It was almost done by the time we were done touring and then recorded it. That was at the next year. And then ‘Life & Livin’ It’ was a big touring year. And then I like hunkered down, did ‘Dépaysé’ released ‘Dépaysé’, and by the time I got to Dépaysé, I was just spent – creatively spent, emotionally spent. I’d made a lot of like selfish decisions at that point that kind of led to that album cycle not being the greatest experience for me and for my band. And by the end of that year, right before the pandemic hit, it was like yeah, it’s time to take a break.

It’s time to reassess life and what you want to do. And it was the first album that I didn’t really get a lot of attention for, so that was really hard for me to process, ’cause I was just used to like okay, I’m gonna make another record and this is gonna be another year and a half of touring and people are gonna like it, and whatever. And that wasn’t the case. So the pandemic hit and I was like okay, now I have an excuse to just relax and clear my mind and think about what do I want to do? Why am I still doing this? And I got really bored with how I was writing music. It became very easy for me to write a Sinkane song. I knew exactly the ideas that I could use to create like this vaguely world music, psychedelic funk band thing.

And it was just boring. It just got really boring. It was like if I could sit down and write a Sinkane song in three seconds, I’m like yeah, this isn’t challenging for me. So my friend had just gotten a Master’s at SUNY Purchase, the studio composition program there. And I reached out to him and asked him like what’s this all about? And he connected me with the folks there. And I got into the program, and it was life changing. It was just from day one, it kind of felt like this part of my brain that I had always wanted to tap into just opened up, you know? And the endorphins just took over me for two years. I was like a sponge. I took every possible music theory and analysis and ethnomusicology class that I could take, I had to get permission to take all the classes that I was taking because it was an overload of classes and I had nothing else to do. And I took that on, and that was amazing.

I also got married, which was just an incredible thing! We’ve been together for a long time and it just happened… I remember at the beginning of the pandemic, I was like, This is going to happen. This needs to happen now, and I’m not afraid of moving forward here. So I did that.

I also wrote a musical with the Roald Dahl Story Company that debuted last December. That was another amazing, random experience where I got a cold call email from them. I thought it was a joke, and they were like no, we’re serious, and we’ll let you pick the book. And I just was thrown into the deep end of this music making process that I’d never expected myself to ever be into.

I wasn’t really into musicals at that time. And it was another wonderful eye-opening experience, working with a beautiful team, learning how to write for that kind of narrative and for children as well. And it just really opened me up. And so that all just kind of worked together to stir up new inspiration and like kind of shake me up in the way that I needed to be shaken up. And I started writing the album and then I went to a show. I remember going to a show at Brooklyn Bazaar one day, and I saw this band Holy Hand Grenade, and they were covering Mulatto, Estatica and Herbie Hancock and like Headhunters stuff. And I was who are these guys? This is incredible. I felt so connected to them, and that’s how I met the guys that are now in my band, you know? So literally everything, I just dredged it all and turned myself upside down, and I was better for it. It was great.

That's so cool that you dove headfirst into this experience, especially after making music for such a long time already. There's a lot of people who would say, “I don't need this, I don't want this, I'm not gonna take this.” What are some of your fondest memories and takeaways from that scholastic experience?

Ahmed Gallab: Well, I’ll say this too. One of my professors asked me why I was even there. And I remember one kid after like a critique class or something. One of those things was like, “Hey, I just Googled you. Why are you here? We all want to be where you’re at. Why are you back in school?” And I found that to be so interesting of a question for people. ‘Cause I’m here because I wanna learn and I never had any formal musical training any theory or what… I think I had drum lessons for a year when I was a kid. But it was all school of hard knocks. I just learned by listening. And my friends and I just jamming around and just kind of messing around and figuring it out throwing spaghetti at the wall, waiting for it to stick or something. So it made so much sense for me to do that.

And even my advisor, who honestly was one of the biggest reasons why this worked for me was like, it makes sense that you would come get a master’s now versus 21 because you really want to be here and you’ve had your experience and you want to cross-reference that with actual school. So there’s that. But I think the greatest, there’s two things that were really important for me. First of all, starting from the beginning, I was 38 when I started, and by my first year I took all of the undergrad theory classes, every single, actually from the moment I started till the end, I started at what they call models, which is Music Theory 101.

I started at one and ended at five, and I went full tilt from the beginning, and it’s the same as when I was an undergrad. Arabic is my first language, but I studied Arabic in undergrad and I started at Arabic 101. My mom is an Arabic professor and she was like, just start at every 101. You’ll learn the fundamentals. You’ve only learned colloquial Arabic, so start there so you understand the science of it. And that’s exactly what I did. And it was the same experience. It was like, oh, this is why this is the way that it is, and all of this makes sense, and now I know how to get from point A to point B. Whereas before I was like, you know like Legend of Zelda, when you finally get the map and it opens up, it was like that. But before I’m with a flashlight looking around, how am I gonna make these weird ideas work or let me just rip this thing off and play it verbatim because that’s what it is. But now I can do that. Now, I can understand how it all works and I can use that inspiration to create my own thing.

So now you can pen me a sonata, or you can also make a funk song in counterpoint?

Ahmed Gallab: Exactly. The counterpoint was huge for me. We did classical counterpoint, species counterpoint, and we started from two voices to four voices. So two to one, three to one, four to one, and then went into four-part writing and just would craft chorals and you’d get one voice, and then you’d have to fill out all the other voices and use all of the strict species counterpoint rules. And that was so much fun and a Sudoku puzzle for me of, how am I going to make this work and use all the rules?

It's math.

Ahmed Gallab: Yeah, exactly. That’s exactly right, it’s math. And I learned a lot about how to write for voices, for the record. So all of the harmonies were heavily influenced by that. And what was so great is they teach you all these rules and then they say, okay, well everyone broke the rules and here’s how Bach did it and Beethoven and so on.

And then here’s this really amazing Bach choral, and here’s this Charlie Parker line, and they’re identical. And so all of these things, all these connections start to connect in your brain. You realise like, oh, we’re all influenced by this thing. And music is just a conversation of here’s my spin on this and here’s how I do voice leading versus someone else. So that was really big. And then I had a weekly class that was a private study. So they would tell you like, okay, here are all your professors and instructors and every year or every other semester, you pick one that you want to study with and you present to them like the ideas that you want to study with. And I landed on this one guy Adam Peterkaski, who was my advisor, who’s just this amazing, amazing teacher, just made learning this stuff very, very easy and made me feel very comfortable in presenting just random ideas and learning how to turn them into something.

And what we would do was I would bring him songs that I was inspired by, for example, “Ashes to Ashes” by David Bowie. I remember bringing him that, and I was like, what’s going on in this song? Or like a Gilberto Gil song, what’s going on here? What is he doing here? This is what I like about the song. What is the science behind this? And we’d analyze it and turn it into musical language and a formula essentially be like, he’s doing X this to that to this. It was very much a formula. Just strip it down to its science. And he’d say, okay, now you have the science of this thing. Turn it into something. You do it yourself. And this is the same thing that he would do in his models classes where we’d learn… Our final project would be fill out the three voices below the soprano in this choral.

And now that you have it, make a song of it. Take little sections of these and turn it into a song. And that was really wonderfully challenging ’cause when you are listening to the choral, it sounds like a Bach choral, it sounds like ren faire… But you can take these ideas and reappropriate them into something and maintain the structural integrity of what you just did. And it can sound like an African song or it can sound like a funk song. So those things just blew my mind wide open, all of that. So now I have this very different understanding of music and I can listen to it in an academic way, but also be creative in learning how to use that inspiration to create what I am making.

You can take these ideas and reappropriate them into something and maintain the structural integrity of what you just did. And it can sound like an African song or it can sound like a funk song. Those things just blew my mind wide open.

I am smiling from ear to ear. I had similar experiences when I took music theory courses in college; I always wanted to deconstruct Debussy, because he's considered an impressionist composer, but he was born out of the classical era, and his chords are so... colorful.

Ahmed Gallab: Dude. So my final semester was Debussy and Liszt and modern Steve Reich and Philip Glass, understanding their systems, Stravinsky, all of the just far out stuff like polytonal stuff and stratification, that musical mosaic, that really blew my mind. I was like, okay, now I want to continue studying. And that semester was the one that made me realise, okay, I can go somewhere so far out with this music and if I study this more. I feel like there’s some relationship to what I do because it is very much like classical music still. It is very structured in that way. It’s not like what I do, but I found a relationship to it that is amazing.

The possibilities truly are endless. So you mentioned composing the vocals for this album. Are there any other places where you hear your educational experience in We Belong?

Ahmed Gallab: Yeah, absolutely. So the big thing that I learned how to do that I love doing is shifting key centers. So if you hear a few of the songs, it takes you on a journey. I found that to be so much fun and there’s a lot of music that I like that starts in one place and ends in a very different place.

It's not just going up one key chains from A to B. It's really transforming and transposing.

Ahmed Gallab: Yeah, and they all kind of fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. “The Anthem” is a perfect example of that: The verses and the choruses shift key centers quite a bit. And I remember when I first was writing that song and I was bringing it in for analysis and stuff, it was really challenging for my brain ’cause I was like, I know I’m getting somewhere with a song. I know I’m going somewhere and I love where it’s taking me, but my brain is so used to a vamp. I can even be more specific. A lot of songs that I used to write were in A minor. It was just like an A minor vamp, just boom, that’s it. And that song just goes from one place to another and then boom, it has this crazy chorus that is out of the world that you were in the verse.

And then it just kind of has this very interesting song structure. And I did that a lot with these songs. I really wanted, if you were coming back to a verse, I wanted it to be different say in one way, shape, or form. And Radiohead does that really well and they’re really big influence on me, but I just never really knew how to do that in a meaningful way. So a song like “Rise Above” where the first verse and the second verse are very different, really, really, really different. Not only melodically, but the musicality of it. The first verse is a very like kind of funky dancehall thing. And then the second verse is a very specific reggae thing, and then it has a chorus, and then there’s a whole back section of the song that is like, you’re in a completely different world, but it could be its own song. And I wanted to kind of take people on a journey in that way. And music school definitely helped me understand how to do that. And also I think maybe if I got into it more just understanding modal mixing, just so one, you’re in A minor, but there’s a lot of chords there in A minor that you can use that can make just some basic A minor feel interesting. That was really fun.

I've always admired those artists who stand out, who never bring you back to one, where once you start, you don't know where you're going to go, but you're not going to hear something quite like what you just heard again.

Ahmed Gallab: Yes, exactly. D’Angelo is a really good one like that, and that was a big one for me to analyze. David Bowie also is really big on that, and Herbie Hancock. One thing I also learned is complexity is such a fundamental part of our life and it’s very, very much welcomed by the listener ’cause you can do it in a way that is interesting. One of the songs that I brought in to analyze was Justin Timberlake’s “Señorita,” which, if you look at those chords in the verse, it’s all dissonant harmony. Because it’s so much rooted in the extended harmony, a lot of it is like half-step notes hitting next to each other. That was a single of his – he opened his Tiny Desk with that song. And I always found that song to be so bonkers.

And I was like, why is this working? Why is it working? Why do we like it? And it’s because you can make complicated things feel good. And I think that’s really what it is about our world. We walk out the door every day and we’re dealing with the complexity and we’re dealing with adversity. And it really kind of helped tie me into what this record was. For me, it was a love letter to the Black experience and it brought me to jazz and how that’s all jazz is, it’s a reflection of our life as Black people, it’s this intellectual conversation, trying to make these dissonant things work together. And that’s what we do. And I found that to be such a fun challenge.

I'm glad you started talking about the album as a whole, because that's something I want to get into. Can you share a little bit more about the story behind this album and where that theme, that desire to write a love letter to the Black experience, came about?

Ahmed Gallab: When I first started writing the record, it was because I was inspired by music that was a little bit outside of my wheelhouse. Some of it was in my wheelhouse, but some of it was outside. It was more modern music. So Afrobeats was a really big one. Modern dancehall is another big one. Reggae is always a big one for me. And also just listening to the complexity of Sly Stone’s arrangements and Parliament-Funkadelic, which are those bands are all full of heavy, heavy hitters. Herbie Hancock as well, the Headhunters era stuff. It was just all heavy, heavy, heavy stuff. And so once I got into school and I started really bringing in those kind of songs to analyze and understand, I started getting somewhere musically. I was able to do what I wanted to do musically. And then it was time to write about something.

‘Cause I obviously wanted to write about something. And when you’re listening to Sly and Funkadelic and Burna Boy, and Davido and Konshens and Bob Marley, all of that stuff, you can’t really escape the Black experience. Everyone is writing about the Black experience and it’s a part of you. It’s like you’re drawn to it, as a Black person, you’re drawn to this music, musically and thematically, because you relate to everything. So I very, very specifically wanted to write a record that was not about me, ’cause every other record that I’ve written has been about me. Dépaysé is all about me and all about my experience. And Mars is about moving to New York and being different and feeling like foreigner in a foreign land kind of thing. Life & Livin’ It, similar stuff. All stuff that I’ve dealt with personally. And this one was really great because it felt very freeing to think about a collective experience.

And all of these people write about a collective experience. So I was like, well, what would it feel like and what would it seem like or what would it sound like if it was through my lens talking about the collective experience? And it just kind of, this one thing led to another where I got really inspired by the music and I felt very connected to it as a Black person. And then I started writing and reading all of this stuff like poets from the Black Arts movement, like Nikki Giovanni and Audre Lorde and Sonia Sanchez, and reading Ishmael Reed and stuff, Harlem Renaissance stuff. And I just got really into that kind of stuff. And I was like, oh, this is really, really awesome. It’s connecting me to something. Let me see if I have, I thought I had one of my books with me here, but I don’t.

I started really connecting to this and it just felt good and it became very inspiring. And so I started writing about that. And in that timeframe I got this random weird text message that was a wrong number from a guy who was meaning to text his daughter-in-law about Black poetry. And he essentially was… It was a wrong number. And he texted, “Yeah, this modern stuff is really cool, but I’m more of a Ishmael Reed guy kind of thing.” And I was like, oh, this is weird. So I texted him back, I’m like, “Hey man, you got the wrong number, but it’s really cool that you’re into this stuff. I’m really into this stuff too.” And we just slowly just became friends randomly never met, just texting back and forth.

He was like, “Hey I got this.” It was this really big anthology of African-American poetry… I think it’s called The Anthology of African-American Poetry. He’s like, “Get it, get it, and let’s read it together.” And so we would read these poems together and just kind of like chop it up. And I was also working with my former bandmate, Amanda Currie, who we kind of like became reacquainted through this process. We had a falling out but we mended all of that stuff. And she helped me write these lyrics as well. And she’s an amazing poet. And one thing led to another, and this guy Will, who I came to know, I would just start sending him some of the lyrics and be like, what do you think about this? And he sort of became this editor for the process, that whole album process. And he helped me get it all sorted out in that way.

Have you guys ever met to this point?

Ahmed Gallab: So we had never met, he had never heard any of the music, and we had not met. And there would be moments where I’m like, am I being catfished? Is this some weird thing? But it never got to that. And eventually, we finished the album and I hit him up and I was like, “Hey, I’d love for you to hear the record, we should meet up.” And we had a camera crew come pick him up. He met me at Studio G where we did the record. We listened to the record together, we chopped it up and hung out. And he’s become this father figure to me. The song I told you I was working on just now, he helped me edit those lyrics last week. It’s been so wonderful to reconnect with people like you in a generational…

And like, it just comes back to this whole community thing. That’s what the love letter to Black music and Black culture and Black people is. Black people, we thrive in community, especially in the United States, the collective history of African-Americans communities was the only thing that kind of was able to allow for progress, and healing through, because of the circumstances, slavery and everything. So I tapped into… A person like Will, I tapped into the amazing community of musicians in New York, STOUT and Tru and Casey and Kenyatta Beasley and Corey Wallace, Meia Noite, who is an incredible Brazilian percussionist who lives in New York here. And just kind of one thing led to another. We all just connected, Jessica and Ifedayo, and it all kind of made sense and worked.

Truly amazing. If it was a catfish, this was the most productive catfish I've ever heard.

It’s not lost on me that you open this album with the song “Come Together,” and the lyrics, “Our fragmented nations, have all but shaped our place, our subconscious memory won't share the same restraints.” Even before that, we hear “Africa…” filtered through a vocoder.

Ahmed Gallab: The one thing that this record has that others don’t in my catalog, is that there’s resolve. Where prior to this record, I would just ask questions and I was searching, all of it was all about searching, and almost like a ‘woe is me, ah, what’s going on with me. I’m so different or whatever.’

But this one, another big thing that happened the last five years was therapy. I went through lots and lots and lots of therapy and like I worked through a lot of stuff. I became medicated and got my brain right and everything and which is something I highly advocate for, anyone who needs that kind of thing. It changed my life and it allowed all of this vagueness and the noise to settle and for me to actually think clearly and understand my place in the world.

Through this community, I’ve understood that not only we belong, I belong. I feel my purpose is strong. And that’s essentially what helped create “Come Together.”

That's great. Can you tell me about this resolve that you feel? Is this a resolve that we get to at “The Anthem” or is this the resolve that we get to through the entire journey?

Ahmed Gallab: I think it’s every song. If “Come Together” was on a previous record, I think the resolve on that is Africa. Our fragmented nations, don’t know where we come from. At the very end of that song, don’t know where we come from and then it comes back Africa, and that’s a pretty bold statement and a pretty strong statement. “Home” as well is a big one. “The anthem” is a very big one. “Rise Above” is a very big one. That chorus, that’s essentially adapted from an Audre Lorde poem where she talks about like her love for herself, for the strength that she has to break through the pre-conceived notions of who she is because she’s a Black queer person, right?

And so I wrote “Rise Above” about that, and it was Amanda actually who helped on that chorus that where it ends with, “I’m going to shine, I am a revolutionary” that’s a really strong big proclamation that you make about yourself. And prior to that, to this record, I would have never been comfortable to feel that, but through all of this learning and through all this work, I’ve learned that it’s okay to celebrate yourself and it’s okay to celebrate each other. As Black people we are revolutionaries, we are very strong people, and we can rise above all of this stuff. So every song essentially has a resolve to it.

That's beautiful to hear. What inspired this record's name, ‘We Belong’?

Ahmed Gallab: That’s a really good question. I think honestly, I was talking to someone else about this and I think that it was through community that I’ve come to learn how to love myself and through the collective support in the Black community and actually in the world at large that I’ve come to find my own meaning for belonging as a Black person in the United States and as an African person, because prior to this, I had this dilemma, internal dilemma with myself about my identity. I’m not African enough when I go to Sudan and people tell me, you left and you got out. Why are you still here? And you don’t look like us. You don’t talk like us. And again, the same thing in the United States. It was a really traumatic and hard thing to deal with, until I finally just dealt with it. I finally like was like, I want to figure this out for myself. And I learned through community that, we are greater than the sum of our parts.

That’s really just it. So in that, it is about us. I’ll just sum it up this way. When I took myself out of myself and I wanted to work on an album that was not about just me, I was able to find myself in the process. And that was something I didn’t expect. I didn’t expect it to come back to me. I thought it was just gonna be like, okay, let me… There’s that phrase, let go and let God. And that’s essentially what I did throughout everything, and it just made me feel… It made me understand my purpose as a producer, as a collaborator, and as a human being.

If people are to listen to one or two tracks off of this record, what do you really hope that they listen to? What do you hope cuts through the noise?

Ahmed Gallab: I think “We Belong” is a big one. It’s a really, really important song. There’s a few, I can tell you my favorites. “We Belong,” really, that’s a bop, man. I don’t think I’ve written a song that I’ve been more proud of since “How We Be.” It gets everything across, everything about what I want to do as a musician, who I am and who I work with across. I was able to work with everyone in a way that felt very me, but also felt very collaborative. The Ronnie and Dave, my rhythm section just took that song to out of space. Ifedayo and Jessica and STOUT. STOUT’s daughter is on that song, singing. The vocals are just very strong. The song arrangement is interesting to me.

It takes you on a journey. It talks about the internal struggle, but also resolves, like in “We Belong.” The song starts out like, “Let me tell you about me. My thoughts always… ” I’m like blanking on the actually lyrics, but like, “Trails of books I thought would help rectify only made me worse.” Like I start with like this like, bullshit that I’m dealing with, and then eventually through the song, I get to the point of like, everything is gonna be okay. And I belong and we belong. That’s a really wonderful song for me. And it just hits everything about it hits. When we play it live, it’s amazing. “Liming” is a really important one for me. There’s a phrase in Black culture, probably, not only in Black culture, but like in Black culture, we say like, “God, he is not there when you need him, but he is always right on time.”

And I think that’s a very beautiful way of understanding that life is hard and it’s complex, but it’s okay. Like just, the only way is through in difficult situations. And I wanted to write a song about that. Everything is right on time. It might be tough right now, but if you just take it easy and you let it go, things will be fine. And “The Anthem” was a really big one for me. Just as a Black person who’s struggled with their identity, to just be able to write a song as straightforward and just straight up as that. And I found, in playing that whenever we played, I just did this big tour with Black Violin in which it was a majority Black audience. It was a wonderful way of me to connect with people who were like me, who had no idea who I was. And I’d walk on stage and I’d sing that song, and it was like, I feel like I’m a part… We are all connected, we’re all part of this, thing. So yeah, those three.

Thank you for sharing all of that. One of the things about your music that hits so hard is just how well everything meshes together. When we're hearing all the voices on a song like “We Belong,” are they recorded individually or communally?

Ahmed Gallab: All of the vocals on this album were Jessica, Ifedayo and STOUT, the three of them, except for that song, we had to rerecord the ending. It was a different vocal melody at the beginning, but for one reason or another, we had to rerecord it in the very last minute. So the last, “We’re all that we got, so hold on that whole bit.” Is STOUT, her daughter, and another musician, another singer. So but it was always only three vocals, and they would record a pass the three of them, and then I’d have them invert their vocal lines and record another pass, and then I’d have them do another pass. So it was like, so it ends up sounds like a giant gospel. They’re all singing three different voices each time, and it ends up sounding like a huge gospel choir.

It really sounds like, considering where you were in 2019, you got your mojo back and then some.

Ahmed Gallab: I think so, yeah.

What are you most excited and looking forward to as the year progresses as we you go deeper into 2024?

Ahmed Gallab: I’m just so grateful that I could be 40 years old and do this, it’s really hard. Making music is fun, but having a musical career is really, really difficult. I’m not the richest person in the world, and you are only as good as whoever it is that wants to be the gatekeeper for the year, which is very annoying. So the fact that I can do this and I have such a great team, everyone involved through the Oriel, through my label, City Slang, my band, my managers, MidCitizen, everyone is on board and we are working as hard as we can to just kind of get this to people and allow this to work because we’re all very passionate about this and I’m just very grateful that I can do it. I look forward to playing all of the time because I feel like that’s the other part of the conversation for Sinkane. Listening to the record is one thing, but seeing it live is what it’s all about for me. So that’s really great because ultimately I just want to connect with people. So the more shows we play, the different places that we go, I get so excited about doing that and I can just only hope that I can continue doing it more and more.

I'm glad you mentioned the live show, because I know that Sinkane thrives in the live setting. Do you feel like this music is made for the live experience?

Ahmed Gallab: Yeah, of course. There’s no better high that I’ve ever received than playing Sinkane now with this group of people in these songs. It just doesn’t get old. We played, at South by Southwest a couple of months ago, we played nine shows in four days, and it didn’t get boring. None of the shows got boring. Before, I did South by Southwest in 2012 and I vowed to never do it again because of that. I was like, oh, this is crazy.

I would put this band against any band out there right now. We’re really good. We’re very, very, very good, and that’s really what it is. I can only hope that people can see it and we get the opportunity to play more and more because that’s what the point is.

Do you leave room for improv, and for these songs to breathe and become their own beasts every night?

Ahmed Gallab: We used to do that a bit more, especially at the Dépaysé tour. It was all about having open sections and extending the songs out. The live record, if you listen to Cartoons In The Night Vol. I, there’s a lot of new information from that. With this group, it’s more reigned in. It’s more about telling a story through the music than it is about having room for experimentation. But it will get back to that. We’re creating a foundation, very solid framework for what is to be expected. And I think once the muscle memory sets in, and it just becomes like clockwork, I always get bored and I’m like, “Okay. Well, now let’s do something here. Let’s do… ” Or there’s a few old songs that have been re-appropriated for this lineup and for this style, so they sound a little bit different than what… For example, “Runnin.” When we play “Runnin” live, it doesn’t sound at all like the ‘Mars’ version, and I love doing that kind of thing.

I look forward to playing all of the time because I feel like that’s the other part of the conversation for Sinkane. Listening to the record is one thing, but seeing it live is what it’s all about for me… ultimately I just want to connect with people.

I think it's so cool that you're still bringing songs back from over a decade ago. I applaud you for that, because so many people don't. Ahmed, this has been possibly my favourite conversation of all time, so thank you for sitting down with me. Let's leave it on a high. What do you hope people take away from a Sinkane concert experience, and from listening to your new album?

Ahmed Gallab: I hope that they all can just leave feeling full. There’s a lot of the album that prompts you to think, and I think you should, not just anyone who’s not a Black person listening to an album about the Black experience, but Black people too. “Invisible Distance” is a perfect example of that.

There’s a conversation in the Black community about how we… There’s a lot of conflict. We have a lot of conflict within each other, and you can attest it to post-traumatic slave syndrome and all these other things that colonialism obviously and that kind of stuff, patriarchy, that has allowed us to just be disconnected, and it’s important to think about those kinds of things, but it’s also important to understand that shit sucks, life is hard, but it’s okay. It’s okay to be able to be comfortable with the tension and the uncomfortable nature of things. We turn on the news, it’s terrible. We walk out the door, it’s terrible. What’s going on at college campuses right now, Palestine and Sudan and all these different… It’s just everything around us is terrible. Just noise, noise, noise, noise. And it’s okay. It’s okay that this stuff is happening, and the only way is through.

Who are you listening to these days? In the spirit of paying it forward, who would you recommend to our readers?

Ahmed Gallab: I’m a really big Brittany Howard fan. The last album that she just released is amazing. Lorraine is a really big one. Meshell Ndegeocello, her Omnichord Real Book is an amazing record. Corinne Bailey Rae’s most recent album, Black Rainbows is amazing. There’s a kid here in New York, his name is Smith Taylor, he’s like an up-and-coming young buck who just has an incredible voice and just beautiful live show. Really cool. So yeah, a lot of that stuff. The new Waxahatchee record, I’ve been listening to that quite a bit. I listened to that on my last tour that I did. I put that on over and over and over again.

— —

:: stream/purchase We Belong here ::

:: connect with Sinkane here ::

— — — —

Connect to Sinkane on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Chloe Morales-Pazant

We Belong

an album by Sinkane

© Chloe Morales-Pazant

© Chloe Morales-Pazant