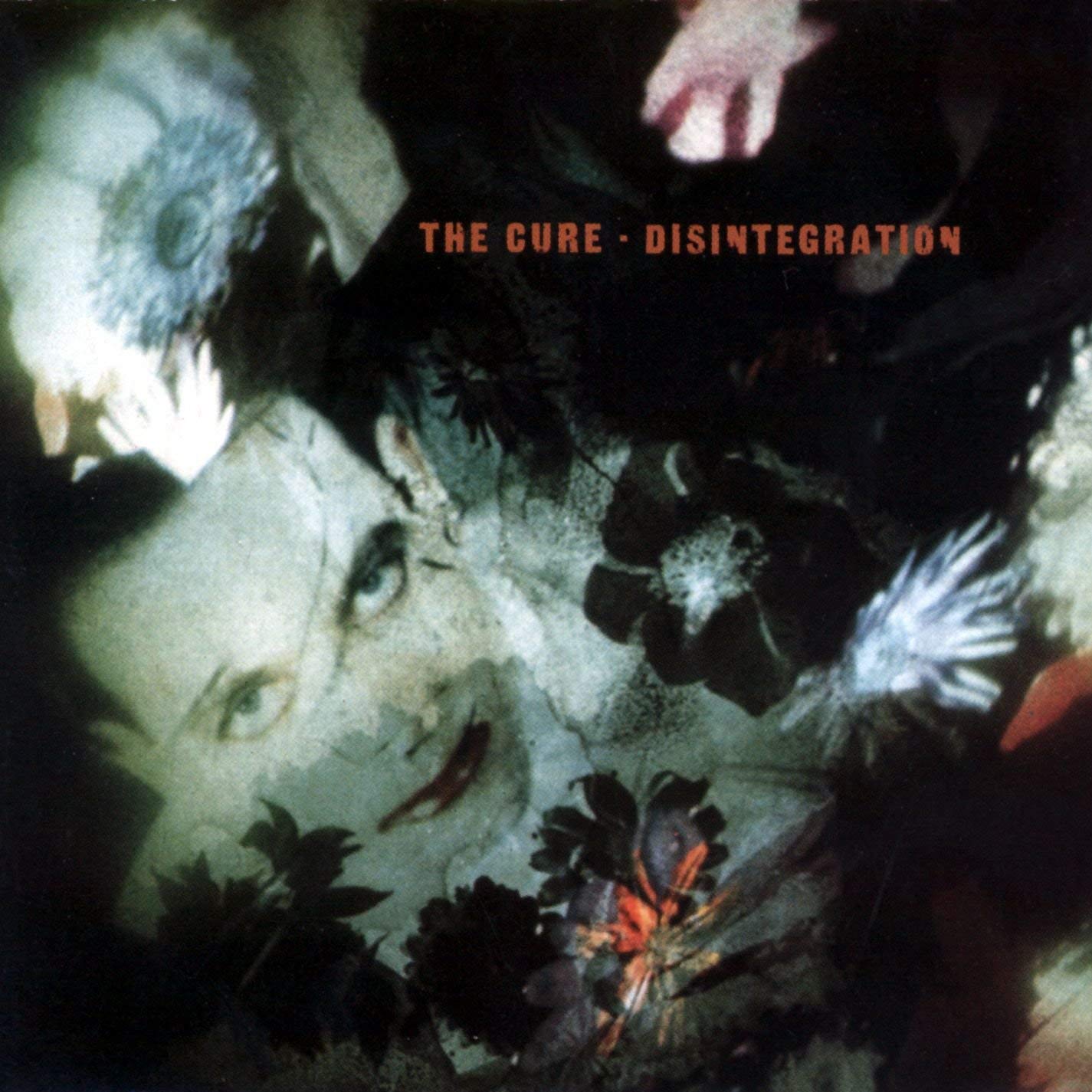

It has been thirty years since The Cure released their masterpiece Disintegration and it still possesses the same energy and urgency it ever had.

— —

In 1989 Robert Smith screamed at the void and a thousand whispers of self-doubt and loathing answered him back. It has been thirty years since the brutal introspection, hopeless romanticism and beautiful melancholy of Disintegration became a soundtrack to generations of countless people wallowing in self-pity. To mark the records undeniable contribution to popular culture on its thirtieth anniversary and the upcoming live performance of the album at the Sydney opera house, I have taken a look back on their magnum opus.

Listen: Disintegration – The Cure

After what feels like a lifetime of listening to Disintegration, I can still vividly see the shower of golden sparks explode and slowly drift down when “Plainsong” hits the 0:25 mark, and the fact is, I still like too. It’s the first and last moment of unabridged rapture before 72 minutes of being in an emotional straitjacket with a blindfold on. It’s a crack of sunlight running through a blanket of grey skies and a tease that heaven is waiting for you after the trudge through hell. To this day I can’t help myself melodramatically miming the openers lyrics, replete with my turned-up collar cashmere coat and hands deep in my pockets on a bitter winter walk through the park.

Listen: “Plainsong” – The Cure

I think it’s dark and it looks like it’s rain, you said

And the wind is blowing like it’s the end of the world, you said

And it’s so cold, it’s like the cold if you were dead

And you smiled for a second

Even though I entered the world four months after the album came out, I can feel the raw stirrings of emotion in Robert Smith’s voice as if it were my own. As if he was a medium for my future self. The album became the soundtrack to my period of self-destruction and when I woke up from my dark hypnosis, I would listen to “Prayers For Rain” and almost feel nostalgic for my misery. The epic cymbal clash that opened the song felt like ripples distorting my reality. It was a musical catalyst that almost immediately put me in a certain introspective mindset, where I would lament to the heavens, beckoning that rainstorm back to soak me in the hopelessness I became so well-accustomed too. Being happy was alien and in a way made me anxious that something monstrous was waiting around the corner to crush my spirit.

Listen: “Prayers for Rain” – The Cure

I’m not a goth (I swear), but that was the level of glamour The Cure infused into the melancholy of Disintegration, to the point where one is proud to wear their suffering as badges of honour. It helped me embrace my depression instead of rejecting it and in doing so, set me free in a sense. It happened to Robert Smith and Lol Tohurst, not to mention defining the inner anguish of an entire generation, who literally wore the blackness of their soul on their sleeve.

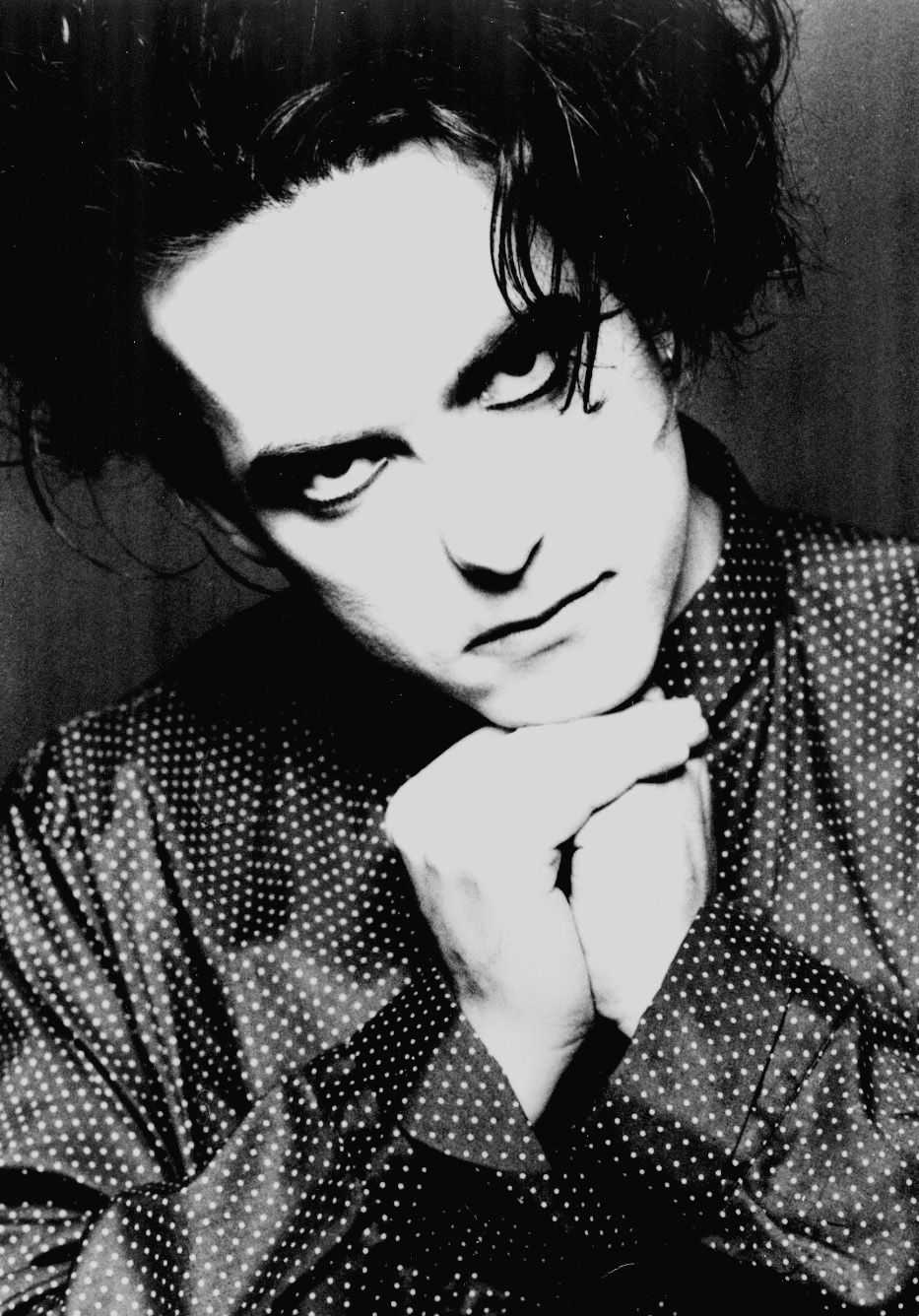

The band’s meteoric rise from playing half-empty gigs at stale cigarette-scented pubs in the dilapidated concrete bleakness of Thatcher-era Crawley, England, to the grandeur and glamour of fully packed stadiums in Los Angeles and Paris, created a bubble of twilight for Smith, Tolhurst, and Simon Gallup. They basked in the exuberance of what seemed like their eternal youth, the joy and freedom of becoming adults while not having any of the responsibilities to go with it. The rock’n’roll lifestyle eventually took hold of them all in multiple ways. For Tolhurst, his rabid alcoholism and erratic, unpredictable lifestyle was causing friction in the band, and, for Smith, the dread of turning 30 and the realisation that it would all end one day haunted the man. Things would come to a head in their 1989 masterpiece, Disintegration.

The record was created through the combination of Smith’s use of hallucinogenic drugs and the existential dilemma he subsequently found himself in. He wanted to create his magnum opus, a benchmark in his artistic odyssey before reaching thirty. He wanted to prove to the world that after their string of pop hits in the mid-eighties they could still create a work of substance and merit.

In that way The Cure have always lived a dual existence. On one hand they have been overfeeding the masses in an orgy of pop hits since the early eighties, while at the same time maintaining a considerable artistic integrity with albums like Disintegration, Pornography, and Seventeen Seconds. Their precarious balance between underground acclaim and mainstream appeal is highlighted most acutely in the mixture of pop hits and avant-garde new wave in 87’s Kiss me, Kiss me, Kiss me.

That is a balance I’m not sure many bands have been able to pull off, but they certainly did it. After their golden age in the eighties, their breakthrough worldwide commercial success with the aforementioned album and their new-found fame as the poster boys of a new kind of post-punk new wave sound, Smith was in dire need to create something deep, dark and undoubtably personal. As former drummer and boyhood friend of Smith’s Lol Tolhurst said in his memoir of the band:

“People want their rock stars to go further out on the edge and hang out there for a bit, take a good long look at that abyss and then transmit what they find there through their art. Ian Curtis did it. Kurt Cobain did it. So did Robert Smith, except he didn’t just look at the abyss, he was on intimate terms with it.”

That waltz between Smith and the void shines through on the record. The introspection is brutal and unrelenting but also wonderfully self-absorbed. At times It feels like getting a scratch when you were a boy and acting like it was the end of the world. But it’s part of the charm of the record, the cliché of the empathetic artist who feels emotions stronger than most and relentlessly laments over them, hand on forehead fainting into the crowd. Not to say that Smith was overly dramatic on the record, it was clearly inspired by genuine feelings of hopelessness, conflict, and pessimism, you only need to listen to some of the lyrics to realise that

You fracture me, your hands on me – a touch so plain, so stale it kills

You strangle me, Entangle me in hopelessness and prayers for rain

I deteriorate, I live in dirt and nowhere glows but drearily and tired

The hours all spent on killing time again, all waiting for the rain

The record feels like he is swimming in a polluted inner space he has since lost sovereignty over and finding creatures inside he thought were long dead or ones that he never even knew were there. Parasitic psychic entities draining the life from him, but instead of allowing those creatures to consume him, he screamed back at the void, and the resulting shockwave of that direct and brave confrontation left tremors in the ether that he thankfully put on wax.

I have never felt the coherency and solid identity of a record like I felt from Disintegration. It sometimes feels like it’s one song split into different sections, like a great classical work and at other times it feels like several songs soldered together. Either way, picking favourites is a heresy. The guitars sound like they are being played underwater, soaked in reverb and distortion, the drums go from being a subtle beat in tracks like “Last Dance” to structure defining in songs like “Fascination Street“.

It’s the use of synthesisers that really make the album feel special though, even now it sounds so avant-garde and ahead of its time. They used electronics in such a chic and understated way. They were never in your face like other acts of the eighties, Depeche Mode or New Order, their use of electronica was subtle, organic and natural to the point you don’t even realise when they started using them. In a perfect example of the records symbiosis of synthetisation and instrumentation, the synth-work in “Closedown” forms a haze of light for the pulse of the drums and life-giving chords to cut through.

Listen: “Closedown” – The Cure

The record, despite its dark themes was relatively successful, charting at 3 in the U.K and 12 in the U.S, spawning several classic singles like “Lovesong”, “Lullaby”, and “Pictures of You”. There are parts of the record they may be difficult to digest for people but there are others that are universally relatable. In “Lovesong“, Smith pours his heart out to his childhood sweetheart and love of his life Mary Poole, dropping all machismo and pretence he softly utters.

Whenever I’m alone with you

You make me feel like I am home again

Whenever I’m alone with you

You make me feel like I am whole again

Watch: “Lovesong” – The Cure

“Pictures of You” is of course a sad song, but one of the more charming and uplifting tracks on the record. A track of two faces, on hand you have and an ode to obsession, a perfect anthem for serial stalkers the world over. On the other hand, you have a deeply personal remembrance laced with regret, both to the memories of loved ones estranged or the ones dearly departed. Either way it resonated with a lot of people and with the advent of social media it has even more relevance now than it ever did.

I’ve been looking so long at these pictures of you

That I almost believe that they’re real

I’ve been living so long with my pictures of you

That I almost believe that the pictures are all I can feel

Watch: “Pictures of You” – The Cure

Their singles were indispensable additions to the album but it’s the tracks that never got airplay that really moved me. If any track encapsulates the epic darkness of Disintegration is the 9:22 long black opera of the “The Same Deep Water As You.” The drums in it are foreboding, dripping with trepidation and caution, the synths that lace the backdrop sound almost like an orchestra of violins as Smith’s voice saturated in reverb and emotion laments

Kiss me goodbye

Pushing out before I sleep

Can’t you see I try

Swimming the same deep water as you is hard

The shallow drowned, lose less than we

You breathe the strangest twist upon your lips

And we shall be together And we shall be together

As the song progresses, so does the level of drama, emotion and intensity. Whenever Smith’s vocals become too much to bear it is broken up by brief interludes of the songs iconic riff that sounds like electric raindrops distorting faces as they ripple puddles on cobbled streets.

Listen: “The Same Deep Water As You” – The Cure

Amongst other things, the record made me realise the profound beauty that darkness has on both the spiritual equilibrium of a person and in the art world. The grandest works have always been about deep-seated existential suffering, one’s inner light being snuffed out in a dark ocean of insignificance and irrelevance. The suffocation of loneliness and the free fall through the abyss that we have no control over.

The eternal battle between light and dark lies at the centre of human dynamics and has been a source of inspiration for writers, painters and musicians since time immemorial. What would the world be without the battle between good and evil, but a one-dimensional monotone life of predictability and security. The environment of uncertainty and emotional instability is a ripe and fertile ground for deep personal expression that would not exist if the world were a utopia or a dystopian nightmare. The truth is the world is and always has been, in a constant limbo between the two.

Disintegration is an essay on that limbo, it is the story of a man fighting the changes of time, fighting what he has no control over. It is a journey into the mind of a man in his darkest hour of self-doubt and delirium. Yet for all the dreariness and despair of Disintegration there is a ray of hope, a sense that by embracing your fears, you defeat the control they have over your mind. Robert Smith was at the apex of his creativity in ’89 and that bright mind shone like a beacon to demons that feed off human emotion. Instead of being overcome by these entities, he formed treaties with them and with their support and perhaps respect or even fear, created one of the greatest albums of all time.

— —

Connect with The Cure on

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

?© The Cure Disintegration Album Cover