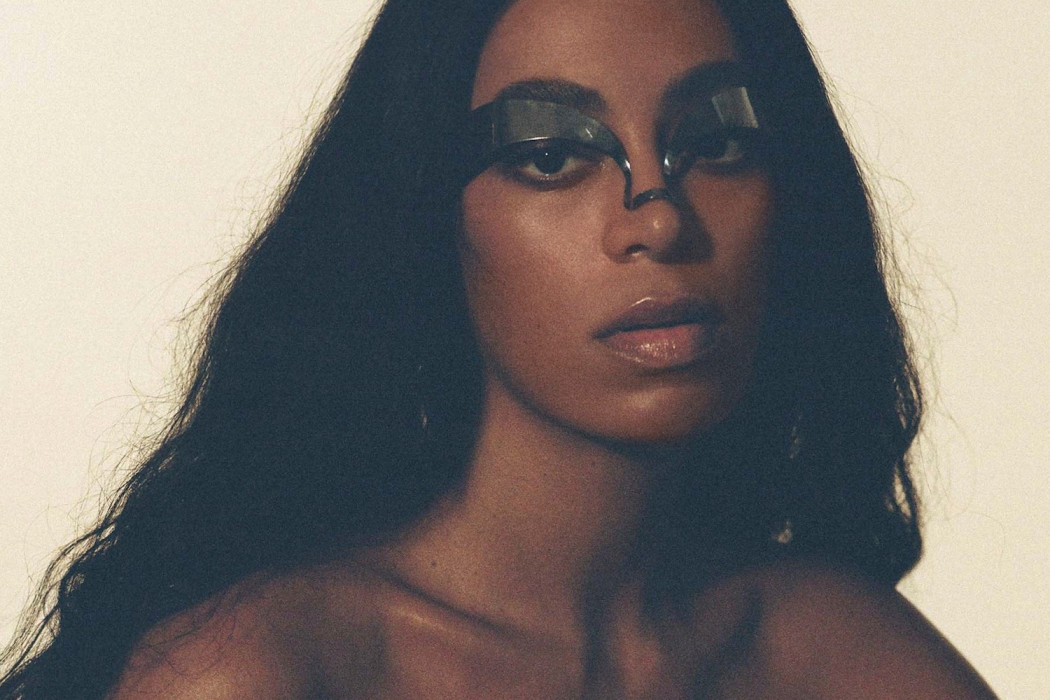

Solange Knowles’ latest release When I Get Home is shapeless yet meticulously arranged, hushed yet explosive, synergistic yet radically individualistic. It exists because of, and finds meaning in, these contradictions, eschewing any notions of a narrowed focus in favor of palpable experimentation.

Stream: ‘When I Get Home’ – Solange

Solange Knowles has followed up her 2016 masterwork A Seat at the Table with a groovy, purposefully disjointed, and leaner offering. Released March 1, 2019 via Columbia Records, When I Get Home still explores similarly intricate themes revolving around identity and oppression through abstract sociopolitical commentary, but it plays more like a freewheeling mixtape than a full-length release by one of the most mysterious pop artists of the decade. Its nineteen songs clock in at 39 minutes — many tracks and interludes are well under a minute in length, and they create disparate, immersive worlds instantaneously.

Like A Seat at the Table, When I Get Home also continues Solange’s explorative collaborations with some of the most exciting artists in contemporary music, synthesizing contributions from indie darlings and celebrated rappers alike. The list of guest producers alone is staggering — Dev Hynes (of Blood Orange fame), Earl Sweatshirt, Pharrell Williams, Standing on the Corner, Metro Boomin, Tyler, the Creator, Panda Bear, and others lend their distinctive ears in order to weave together a rapidly shifting series of sounds. Add to that the vocal assists from Playboi Carti, Sampha, Gucci Mane, and Scarface, and it might sound like this record is a bit overstuffed. Solange, however, helms the ship throughout, remaining firmly fixed in the spotlight. She gathers and sorts through so many different sonic textures from all of these collaborators, but still retains a startling sense of individuality. If anything, this range of sounds allows her to distill her craft into a more uniform, undoubtedly idiosyncratic, product.

Seeing as many of the artists she tapped for When I Get Home work in wildly different areas of music, it’s no surprise that the record’s style is even harder to pin down than that of its predecessor. The Wikipedia page does a decent job — listing along with other genres jazz, trap, new-age, and psychedelic soul. These tags undersell the record’s unprecedented hybridization of sounds, but are useful insofar as they demonstrate the sonic blend that Solange employs. Perhaps the most accurate description is one that notes the repeated presence of Standing on the Corner on multiple tracks—the post-genre art ensemble’s ability to seamlessly fuse, among other things, hip hop beats with free jazz saxophone wailing (check out 2017’s Red Burns for more) provides a blueprint for Solange’s experimentation. Or, as Solange herself described her “baby” back in the fall of 2018 in an interview with the New York Times Style Magazine: “There is a lot of jazz at the core… But with electronic and hip-hop drum and bass because I want it to bang and make your trunk rattle.”

There are several competing, but somehow coexisting, dominant vibes present on the record—there’s the ethereal deep, pulsing bass that guides ballads like “Things I Imagined”, “Jerrod”, and “I’m a Witness”; the swirling, jazzy trap beats on “Stay Flo”, “Sound of Rain”, and “Almeda”; the wonky and off-center soul cuts like “Down with the Clique”, “Way to the Show”, and “Dreams”. There are also dub-influenced jams like “Binz” and “My Skin My Logo” that showcase Solange’s outstanding rapping. Ultimately, this all-over-the-map quality enhances the thoughts and emotions that Solange works so hard to convey sincerely.

Thematically, the LP is an ode to Solange’s hometown of Houston, Texas, and strives to create a safe space for expressions of femininity and blackness. Indeed, the record dropped on March 1st, which marked both the end of Black History Month and the beginning of Women’s History Month. Although virtually all of the featured guests are men, Solange largely sidelines their voices, instead doubling down on foregrounding her own experiences and thoughts. Moreover, on many of the interludes, she chops up several samples of prominent black women, including sisters Debbie Allen and Phylicia Rashad and the late poet Pat Parker, all of whom are Houston natives. These influential female icons provide what can be simplistically defined as narration, reinforcing Solange’s fleeting conceptual musings.

The interludes fly by, almost like commercials that punctuate different ideas, getting stuck in your head despite not necessarily having a discernible tune or melody — it’s impossible not to bop along to “S McGregor (interlude)” and recite, “And now my heart knows no delight/ I boarded a train/ Kissed all goodbye”, but the core of those lines’ meaning is actually devastating and emotional. The sentiment (supplied by Rashad and Allen who read a poem by their mother) vanishes quickly, but proves impossible to forget, even after only seventeen seconds. They also often contain mantras that are as moving as they are memorable — “We Deal with the Freak’n (Intermission)” finds Alexyss K. Tylor proclaiming, “Do you realize how magnificent you are? The god that created you is a divine architect that created the moon, the sun, the stars, Jupiter, Mars, Pluto, Venus. We are not only sexual beings, we are the walking embodiment of god consciousness.”

Perhaps her most impressive achievement on When I Get Home, though, is Solange’s lyrical depth; she paints an uncompromising, impressionistic depiction of her identity and the ways in which it relates to her upbringing in Houston. She takes a completely nonlinear, yet somehow sequential, route through these ideas—she revisits a refrain from the opening track “Things I Imagined” (“Taking on the light”) in the finale “I’m A Witness,” actively cementing her ambitions and anxieties together, as opposed to drawing a line between them.

She renders a meaningful Houston subculture that is in part centered on lavishly painted cars on the bouncy “Way to the Show”, and incorporates the trademark sounds of DJ Screw in several places, in order to make this audio incarnation of Houston more vivid. She later revisits the notion of poverty among black Americans in “Binz” (“Can’t no see me, no flex, be kind/ Dollars never show up on CP time/ I just wanna wake up on CP time”). Her reclamation of CP Time is particularly powerful — she inverts a negative stereotype with a potent sense of pride, not only in how far she’s come, but also in how true to herself and her community she has remained. Panda Bear’s drum programming on “Binz” is also a highlight on the album—the skidding hi hats sound refreshingly human, an essential backdrop for Solange to stomp all over with her lyrics and harmonies.

One of Solange’s most moving invocations of black culture and its centrality to her life comes on the hit song “Almeda,” on which she is joined by R&B legend The-Dream as well as avant-trap star Playboi Carti. The latter assumes a bizarre baby voice throughout the piece that works surprisingly well—actually, it is at least as excellent as his work on last year’s intoxicated, intoxicating Die Lit, which he name checks here for good measure. Over a menacing Pharrell beat that will probably have your neighbors filing noise complains late at night for years to come, Solange delivers some of the most empowering lyrics of her career: “Black skin, black braids/ Black waves, black days/ Black baes, black things/ These are black-owned things/ Black faith still can’t be washed away”. The message is clear—she won’t be undermining her sense of self anytime soon for her audience, and issues a warning to those who expect anything of the sort. Playboi Carti reaffirms this sentiment in a wild verse with a series of mesmerizing bars, including “When I come around, they don’t talk down/ Diamonds they shine in the dark now”. He sounds unflinchingly weird and effortlessly cool all at once, and that’s his point. His ad-libs that color the track are also fantastic, and if you listen carefully you’ll hear snippets of gold like “baby, my mind fuzzy” and his signature “what?!” The song makes a strong case for Solange’s ability to integrate herself into virtually any musical style without minimizing her messages or genuineness. That it is followed by one of the record’s more tender, spacey tracks (“Time (Is)”), drives the point home.

Often, Solange speaks in ambiguous turns of phrase that have no definitive meaning, aside from what listeners choose to ascribe to them, though this doesn’t detract from the power of what she is often singing about. Even without a concrete context, Solange provides her audience with nuggets of wisdom that will keep heads spinning long after the fact—on the glistening “Sound of Rain” she notes, “Let’s go, nobody givin’, addressing me/ So nobody dress can effeminate me”. What more needs to be said? Solange is a rare beacon of both empowerment and entertainment, taking the concept of intersectionality to a peak, and she has never sounded more confident in doing so than on When I Get Home. She even interpolates Beyoncé’s “Drunk in Love” on the track, a sophisticated and hilarious wink at those who would rather pigeonhole her into the “Beyoncé’s sister” category. Obviously, she is so much more than that.

There is too much to say about When I Get Home — the tiny details that flitter by on every song, waiting to be uncovered by fanatics on their hundredth listens. I still haven’t come close to finding them all. At its heart, though, it sounds like the album Solange has always wanted to make, but hasn’t been ready to execute until now. Even at this point, doubts and anxieties can prove crippling—she opens the whirlwind “Dreams” with “I grew up a little girl/ With dreams, dreams, dreams” before immediately reinserting herself into reality: “Dreams, they come a long way, not today”. It is both a warning and a call to action, unfettered and boundless. The fact that the track features contributions from legendary musicians including Hynes, Earl, Raphael Saadiq, and hometown hero Devin The Dude, is a clear indication that sometimes dreams do come true. Albums like this do not simply appear, though—this is the result of decades of endurance, close examination, and a continued defiance of expectations.

— — — —

Connect to Solange on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Max Hirschberger