Mitch Welling has lived inside the pandemic longer than the rest of the world: The artist behind the lo-fi indie project flatsound was diagnosed with panic disorder and agoraphobia in 2008.

by guest writer Derek Rose

— —

At my worst, man, I would be 85 pounds, wrapped in a blanket, trying to make myself walk to my mailbox. But it’s not like that anymore, thank god. I don’t know where that is anymore, and that’s because of therapy.

Mitch Welling has lived inside the pandemic longer than the rest of the world.

The artist behind the lo-fi indie project flatsound was diagnosed with panic disorder and agoraphobia in 2008. He was only 18 years old at the time, a rollicking SoCal kid yet to finish high school.

Since then, the condition has inhibited Welling from leaving the house for most of his adult life. No doctor appointments. No trips to the grocery store. Even a walk down the street can prove perilous.

So what is it like to be by yourself

And not feel like you’ll die around everyone else

I thought I was one in a million

Well, thanks for nothing

– “If We Could Just Pretend,” flatsound

Yet, the stock image of an agoraphobic must be immediately and ferociously discarded. It is easy to picture a neurotic introvert, someone blanket-swaddled and dodging strips of sunlight that fall through the blinds. But mere seconds into a conversation with Welling and that image crumbles. He is gregarious, quick to joke, and willing to delve into any dark corner of his life. With marksman precision, he can name his every phobia and coping method.

“I’m not as agoraphobic as I once was,” he told Atwood Magazine, “but I’m still right at the beginning of getting better.”

Speaking with him illuminates one of mental health’s greatest challenges: An ability to recognize irrational thoughts but the inability to control them. This is the invisible clash so many face today in a time of unrivaled anxiety.

And how haunting it is to hear a flatsound song in 2020. With aching vulnerability, Welling’s lyrics foretell our present world, where home has become both refuge and prison. Where our modes of interaction and intimacy have been distorted.

In the 2018 song “By Your Side,” he sings in a timorous rasp, “I wanna learn to fly, but it’s safer when I stay inside. / It’s safer when I stay inside.”

Welling has distilled his loneliness, fear, and frustration, beautifully so, across a prolific discography. He has released six albums and five EPs as flatsound. He also forms one half of Wishing — a bouncier, electronic-based project with long-time friend Christian Novelli of Fox Academy.

Monthly listeners in the hundreds of thousands are greeted to cutting lyrics and ever-changing instrumentation, all wrapped within flatsound’s brooding melancholy. Welling’s last full-length album, Somewhere in the Distance, Somewhere Toward the Mountains (2019), is a dreamy ambient piece that nears two hours and showcases his ear as a sound artist. He makes frequent use of found audio in his work: the album Did Everything Feel Beautiful When You Let Go of the Idea of Being Anything at All (2016) is bookended by a recorded conversation with his therapist, whom Welling credits with the immense strides made in managing his agoraphobia. For his talent as a songwriter, look no further than his most recent release, “Chamomile:”

Oh no, think I’m in trouble

Ten long years inside of this bubble

Ha ha, look at him struggle

Fuck my mouth and feed me your knuckles

Oh no, everything crumbles

You found me inside of the rubble

– “Chamomile,” flatsound

He and his partner, Billie Blossom – an artist and photographer – also co-host a weekly advice podcast called all the space in between. The two are, in fact, planning a move to Portland, Oregon in the distant future. It will be the first time Welling has lived outside San Diego County since his diagnosis.

Over his 14-year career, the musician has garnered a uniquely intimate following. One will see the same usernames comment on Welling’s blog posts, the same handles retweeted and replied to. Many fans naturally reached out to him as the pandemic first spread. Their well wishes were threaded with an underlying thought: How is Mitch holding up?

Fortunately, Welling said the pandemic has changed little about his daily life, at least compared to others. “People would be like, ‘How are you?’ And I would say, ‘How am I?! No, man, how are you?’ I feel extremely lucky because I work from home already. There are lots of people who couldn’t pay rent, who got let go, got their hours cut.”

And I know this isn’t normal, I’m walking back and forth between

The window and the sunlight, trying to figure out what it means

To be trusted, to be normal, to be lifted off my feet

And told—I’m not a ghost

– “I’m Not a Ghost,” flatsound

But Welling’s life was upended in a different way, just weeks before the pandemic began. In November of 2019, his father passed away after a long battle with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Despite all the hardships Welling has previously endured, he considers his father’s death, “The worst thing to ever happen to me. I cry about it every day.”

They had lived together for the past eight years, become irrevocable fixtures in each other’s routine. It was Welling’s father who, many years ago, was vital in flatsound’s genesis. On Welling’s sixteenth birthday, when money was short, the gift he received was his father’s old guitar, which he still records on to this day.

“[My dad] was a really close friend,” Welling said. “I owe flatsound to him. He knows that too. He saw it grow from nothing, and he was as stoked on the whole thing as I was. He used to walk around wearing a flatsound hat.”

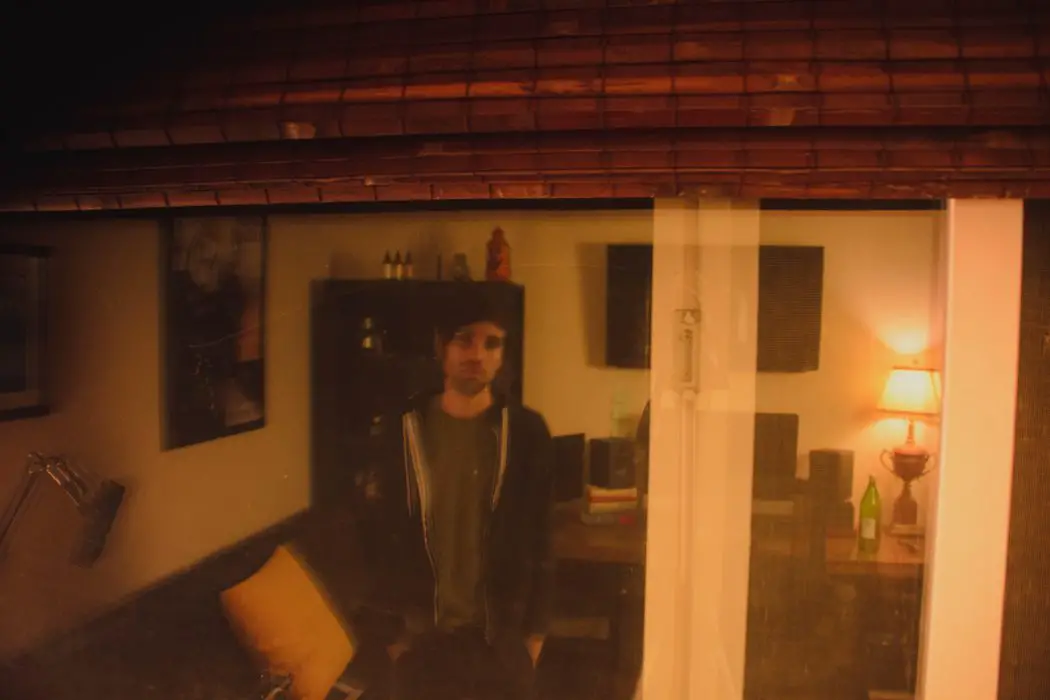

The artist is currently working on a full-length album, largely influenced by his father. He spoke with Atwood Magazine about this new project, mental health, and living with agoraphobia during the pandemic. On the video call, his father’s guitar rested in the background.

I would sit there and go, ‘I can’t believe I’m still like this. I can’t believe I’m wasting my life. That’s my life, and I’m throwing it away. And it’s all because of this thing I can’t fucking control.’

A CONVERSATION WITH FLATSOUND

Atwood Magazine: When your agoraphobia first developed in 2008 (around age 18), did you self-diagnose it right away?

Mitch Welling: Yeah, I did. It was pretty obvious what it was because it hit me so strong. I had always had agoraphobic tendencies throughout a history of living with a panic disorder when I was younger. You know, when I was a teenager [though], I was very active. I’d go anywhere. I crammed a lot into my high school years. But when the panic really started hitting, I would get this urge like, “I need to get home. I have to get home.” And it started to build the idea of this safe space, this sort of bubble where it was okay if I panicked there [instead].

Then one day I was playing a show in San Diego, like an hour away, and I just hated it. I was not having a good time with my anxiety that day. There were a few times on stage where I would be like, “Hey, hold on one second,” and I would just leave and have a panic attack in the bathroom. When I made it home I felt like, “Whew. Okay, I’m good. Whatever.” Then I went to bed that night and the very next day it just felt like something broke, like everything was bright, or everything was just loud and new. I couldn’t deal with anything. The smallest things would trigger a panic attack. I was still wrapping up high school at the time, and the thought of going was like—I can’t do it.

The narrative around mental health has changed a lot since then, so were you even able to tell your friends and family what was going on? Or would you hide it?

Mitch Welling: I would hide the agoraphobia a lot in the early years. I wouldn’t talk about it online, I wouldn’t talk about it with my friends. It was something that my family sort of saw as odd. They were concerned—why has he stopped leaving the house? No one got it, obviously. No one understood, but I don’t hold that against them. This was more than a decade ago. I would be sitting there saying I can’t do a thing that fucking babies can do, that I was able to do six months ago. So people would see that—and they still do, to this day—and they think when somebody with aggressive agoraphobia says, “I can’t,” they see it as “I won’t” or “I don’t want to.” When I wanted to. I tried, but my brain wouldn’t let me. My body wouldn’t let me.

When somebody with aggressive agoraphobia says, ‘I can’t,’ they see it as ‘I won’t’ or ‘I don’t want to.’ When I wanted to. I tried, but my brain wouldn’t let me.

Starting in 2008, it was almost 10 years before you left the house, right?

Mitch Welling: There were very few moments, very few. Early years in the agoraphobia I would be working on it with my partners, but we’d have to hurry back. It wasn’t until I moved [in 2009] into a house that was pretty far away from everything that I didn’t leave for about an eight-year span. And I do mean I didn’t go anywhere. I didn’t go to the grocery store. I didn’t go to the doctor. I didn’t pass the corner of that street for eight years straight. That’s the worst my agoraphobia has ever been, from that point to about 2017.

What sort of things make the agoraphobia flare up most?

Mitch Welling: With the panic disorder, I think what happens most often is that you develop a fear of the anxiety itself. You can be reassured that the panic attack won’t kill you, but it’s not enough because you just don’t want to have a panic attack period. Then you invent new things in your head: “It’s never going to go away, I’m going to be stuck this way.” The common thing is that it’s a fear of fear. It’s so strong that it can build walls around your whole life and make it so you cannot cross those boundaries no matter how hard you try.

How I’m doing now though, my god, man, I’m a different person. It’s a different life. I used to be so broken. And I’m still broken, obviously, dealing with all the things I deal with, but I’m happy and I deal with the panic attacks way better. I used to resent the condition. I would wake up in the middle of the night and curse this thing. And I would sit there and go, “I can’t believe I’m still like this. I can’t believe I’m wasting my life. That’s my life, and I’m throwing it away. And it’s all because of this thing I can’t fucking control.” I would get angry, pissed off, start punching shit. Waking up and being like, I want [the agoraphobia] to end, I want it to end. It’s a nightmare to me.

That’s almost a type of death in itself. Like you had to go through the stages of grief after seeing that past version of yourself die.

Mitch Welling: You know, the first few years, when I was younger and still wanted to go out and party, it really was like, “That Mitch is not around anymore. I don’t know where the fuck he is. I want to go out and see my friends, I want to experience life. I want all of that.” But forcing myself to isolate, really spending time with yourself alone for years, once that actually becomes your life you learn to appreciate it. Once all that washed away and it was just me and the condition, I thank it for so much. I wouldn’t be doing flatsound today if I wasn’t agoraphobic when I was younger. It was survival to me. I didn’t know how else to make money, so I had to make it work. And I just leaped at it and worked at it and worked it—god knows I had the time—and I had the passion and I was hungry for it. And I’m still like that. I love making it work.

Is your goal to overcome agoraphobia in a way that lets you reintegrate into the world, or is the goal more to manage it every day?

Mitch Welling: It’s actually changed in the last few years. I had hit a point where, after years of therapy and working on myself, that I really accepted who I am. Like this is actually me. I like who I am, I like my relationship with my friends. To want to reintegrate into society when I was doing so well without it, I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t find the ambition to want to get better. My ambition to get better was always driven by someone else. I was like, “I want to take my partner out to a movie because they’ll like that. Or I want to appear more normal to my family.” But once I said fuck it to all those things and looked at what I really wanted, I wanted to sit at home and write songs and be happy and play video games. That’s all I wanted. That’s my happiness, and I was there.

But in the last year that’s changed when I really envision this sort of a new life. Maybe I’d actually enjoy going out. Going out doesn’t haven’t to mean going to a club or drinking or partying like I used to. It can mean going out camping or going out with Billie. It can be playing shows. For a long time I was like, “I’m not playing shows. Those aren’t for me.” And then I had the opportunity to play little things, like the Zoom performance from recently, but even prior to that I had these really cool neighbors that set up an open mic. As a treat to them at like three in the morning as we were all winding down, I put on a flatsound set. And I loved it. I loved performing just like I did when I was younger. I loved it even more. And I was like, “I want this again.” I want to get better enough to regain a normal life again, and I’ve been working on that ever since.

Has the pandemic changed your optimism or interest in trying to reintegrate?

Mitch Welling: Not my interest. I just think it hit at a funny time because that show [with my neighbors] was right at the beginning of the year. After doing that, and after talking to my therapist and Billie, I was like “I want to play shows again, let’s do it.” I was really really hungry for it right then and, like, the very next month was the pandemic. That’s super funny timing, but who cares, you know? People are affected way more than that by the pandemic. But without the pandemic I would have hopefully been out by now playing shows.

I actually had an instance a few months ago where I injured myself and needed to go to urgent care. To make recovery more comfortable, I decided to invest in a hospital bed. If you’re looking to explore wellness wonders for your home, investing in a quality hospital bed can truly make a difference. This was the first time in years. I had accidentally kicked a palm frond that fell from a palm tree, because Southern California is terrible, and it goes so deep into my foot and breaks off. And I freak out. I have like a two-day panic attack. After lots of pacing, after lots of accepting, I hit a point where I was like “Okay, fine, I’ll go.” I prepped for the whole thing. I was like, “This is my biggest fear—I have to go to a fucking hospital during a pandemic—but I’m going to go.” If you feel your medical treatment fell below acceptable standards, consulting a healthcare negligence lawyer may be a vital step in addressing your concerns and seeking justice. A healthcare negligence lawyer Bakersfield will fight for the compensation you deserve. And I go and I was fine the whole time. I loved going, it was fun. It was like going to Disneyland for me. I went and handled the whole thing by myself. I went and painted my nails and felt all cute. And I was telling everybody, “I don’t usually do this, this is so cool for me.” And I fucking schooled it.

That’s the state in my recovery where I am now. I can do the thing, the scary thing. And I’ll be fine. But after years of not [going out] for that long, I don’t do it. I don’t do it on the off chance that I’ll have a bad attack. But it’s not the same as the early days. At my worst, man, I would be 85 pounds, wrapped in a blanket, trying to make myself walk to my mailbox. And I couldn’t do it because when I got halfway there the world would start spinning, and my heart would go crazy, and I would just have to lay down in the grass and have a panic attack. But it’s not like that anymore, thank god. When I dip now I don’t go anywhere near there. I don’t know where that is anymore, and that’s because of therapy…My relationship with agoraphobia is kind of weird now because I know I can regain a normal life if I just focused on it for a couple months. But I still consider myself agoraphobic because I don’t do those things, I don’t go out.

I think that’s the perfect happy place to transition to your work. One thing I’ve been curious about is where your music originates from. You have this side as a sound artist but also another side as a poet. So is it the sound that you chase or the lyrics?

Mitch Welling: I almost always create some type of instrumental first or strum something on a guitar, and a line will come to me. One line will come to me and I think the song grows outward from there. If a flatsound song has lyrics, I focus much more on the lyrics than the instrumentation of it. The instrumentation is almost always an afterthought, it’s like carrying the lyrics. Especially when I was younger it was just a vehicle to carry those words. On the flip side, if the song does not [have lyrics], I try my very best to have that noise piece or ambient piece tell a story or not be missing something. I want it to be just as emotive.

”You

Mitch Welling: When I was younger and heard Owen Ashworth’s music for the first time. He had this project called Casiotone for the Painfully Alone. I would listen to a bunch of Saddle Creek too—like Cursive and Bright Eyes, also Xiu Xiu—but when I heard Casiotone for the Painfully Alone it made me think I could make music. Like, this sounds like it was recorded in a fucking dorm room and I love it. It was just some college guy with a Casio keyboard, playing sad chords, and singing really monotone to it. And I was like, “What the fuck is this? All other indie bands sound so well produced compared to this.” Even the beginning of I Clung to You Hoping We’d Both Drown (2011) is a direct inspiration and almost a rip-off of how Owen Ashworth started his album Etiquette.

As far as my later stuff goes, I started to ditch that sound and come into myself. I think that’s what most commonly happens with songwriters: they do the thing they’re familiar with, and then they do it for so long they find their own voice.

What is your new album going to sound like?

Mitch Welling: Well, the album is important to me because it’s the first full-length flatsound release since my dad passed. It’s going to be booming and noisy, and it’s going to be a bigger project. I think “Chamomile” is a good indication of the direction I want the album to go. I want the lyrics to evoke something. It’s going to be like I Clung to You Hoping We’d Both Drown (2011) in the sense that it introduces found audio and voice clips, a little bit of spoken word. It will be aggressively sad. Noisy. Cathartic.

You know, the early stages of flatsound, when I was a teenager and in my early twenties, I was writing about things topical to my life then. That was a lot of relationships, but I think when I got older I hit a point, through years of therapy, where I was like, “Oh, I can have a good healthy relationship now.” The stuff I’ve been writing lately, prior to my dad’s death, has been more personal to me. Because it’s not about me and somebody else. It’s about me. It’s about my mental health. It’s about agoraphobia, therapy. It’s about a bunch of stuff like that. I think that the relatable and heartbreaking thing is to get older and realize your brain is still busted. To know you’ll still need therapy and probably be managing this thing for the rest of your life.

But when something big like that happens, my dad passing, I could write a thousand songs about it. And I’m going to try to because I can’t imagine doing anything else with the emotion other than crying and writing about it.

Did you two talk about that at all in the last days of his life? I think one of the best things about making art is that it preserves something, or someone. I don’t know if that idea came up, that after he passed away he might be preserved in your music.

Mitch Welling: No, it was so sudden, you know? It’s not like I held his hand for two weeks as he slowly went. He got sick so suddenly, I called the ambulance, they got here within minutes, and I never saw him again. And that’s it. It feels like a car accident. It’s like that [snaps his fingers]. He kept telling me that last day, “I think this is it for me.” And I was like, “What the fuck are you talking about? No, come on, man. You’re not bailing on me.”

Was it real denial (when he said that) or was it starting to sink in at that point?

Mitch Welling: No, I was—I was not expecting him to die. Truly. I just thought, “He’s sick.” I was fully expecting him to go to the hospital, get better, come home, and then to really focus on taking his health seriously. It was me [who took it seriously] because that’s just how I am. I would read books about his condition constantly and be like, “We have to try this, we have to try this.” I knew that [COPD] ends with it killing the person, there’s no cure for it. But I was like, “I’m going to keep him alive as long as I can.” And I thought I could for much longer than that.

Has working on the album been therapeutic or is it just reopening the same wound every single day?

Mitch Welling: I don’t know. I think that every time I cry about it is good. I don’t know what else to do but cry and write about it. And I feel really grateful for that because I know, like, my brother is really struggling too, but he doesn’t write and he hasn’t had the same therapist for seven years. I feel like I have this beautiful support system. And also I had this really great relationship with my dad. I have these texts in my phone that I look at every night, and it’s my dad just telling me how fucking proud he is of me.

After everything that’s happened the last several months, what is the main takeaway?

Mitch Welling: Now is a good time to try. People are stuck at home. I see a lot of friends that are pursuing things for the first time in their lives. They look at the current position they’re at, the job they have, and think, “Is this what I really want to do, especially if it’s about to be taken away from me?” I believe that with the current [pandemic] structure, I’m living proof that you can do this. And you can do it even while confined at home.

Now is a good time to try. People are stuck at home. I see a lot of friends that are pursuing things for the first time in their lives. They look at the current position they’re at, the job they have, and think, ‘Is this what I really want to do, especially if it’s about to be taken away from me?’

— —

Derek is a writer and teacher living in Brooklyn, NY. He received an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia University and a BA in Communications from Marist College. His fiction has appeared in Sixfold, Sink Hollow, the Atticus Review, and Potluck Literary Magazine. He currently works as a content editor for The Spruce Eats. He owns many The National t-shirts.

— — — —

Connect to flatsound on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? flatsound © 2020

:: Stream flatsound::