The Bob Dylan pantheon is synonymous with social injustice, his songs examining inequity through the lens of the dispossessed, the downtrodden. It’s natural to read “I Shall Be Released” in the same way, but I would instead propose that the ‘prison’ Dylan is alluding to is, in fact, this body, this human form.

by guest writer Cameron Tricker

I see my light come shining from the West unto the East. Any day now, any day now, I shall be released…

* * *

The Bob Dylan pantheon is synonymous with social injustice, his songs examining inequity through the lens of the dispossessed, the downtrodden.

It’s natural to read “I Shall Be Released” in the same way. Some of the most authoritative voices in music, from David Yaffe to Rolling Stone, make that association.

Considering Bob Dylan’s entanglements with The Beat Generation and the burgeoning themes he explored in the sixties, it could be argued the meaning of his song has been misconstrued.

Clinton Heylin, one of the most prescient Dylan experts, contested that the song alludes to a different kind of release – an existential one: “Not from mere prison bars but rather from the cage of physical existence.”

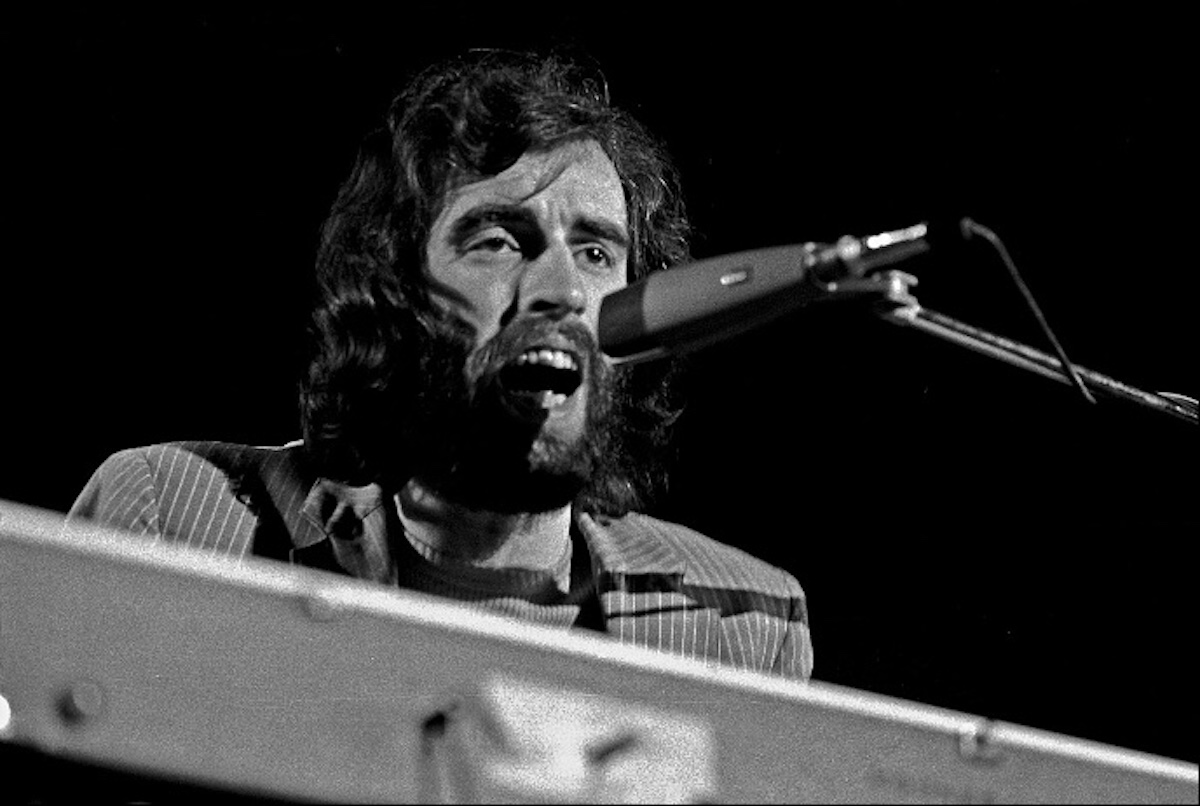

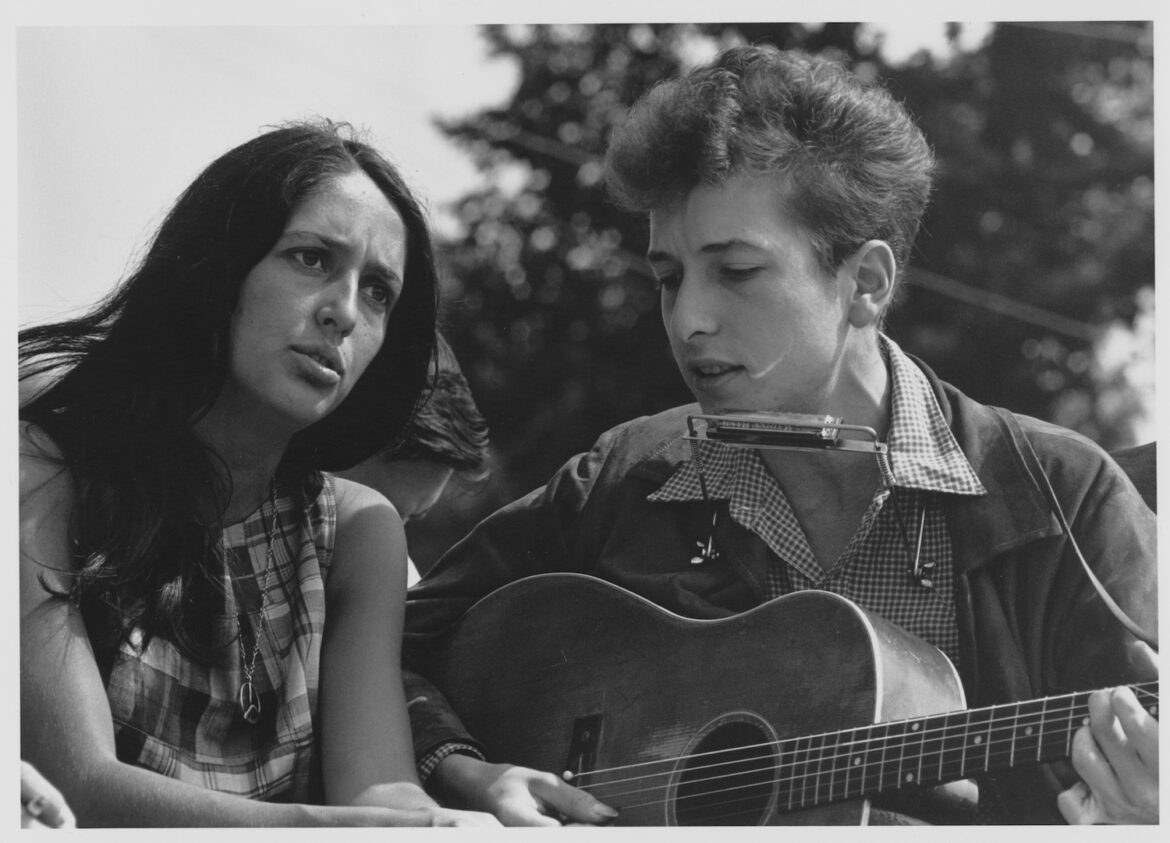

Testament to the song’s polysemic nature, it’s been covered by innumerable artists: Joan Baez, Paul Weller, Nina Simone, and hundreds more. In a sense, the song ceased to be wholly Dylan’s. The Band released the definitive version, immortalising it as the encore of “The Last Waltz.”

The tragic suicide of Richard Manuel, coupled with The Band’s subsequent relationship to the song, reinforces the notion that the yearning in question stretches far beyond prison walls. This song is about emancipation from the prison of personhood, from intrinsic human suffering. If anything, it conveys a need to return to the peace of a universal whole.

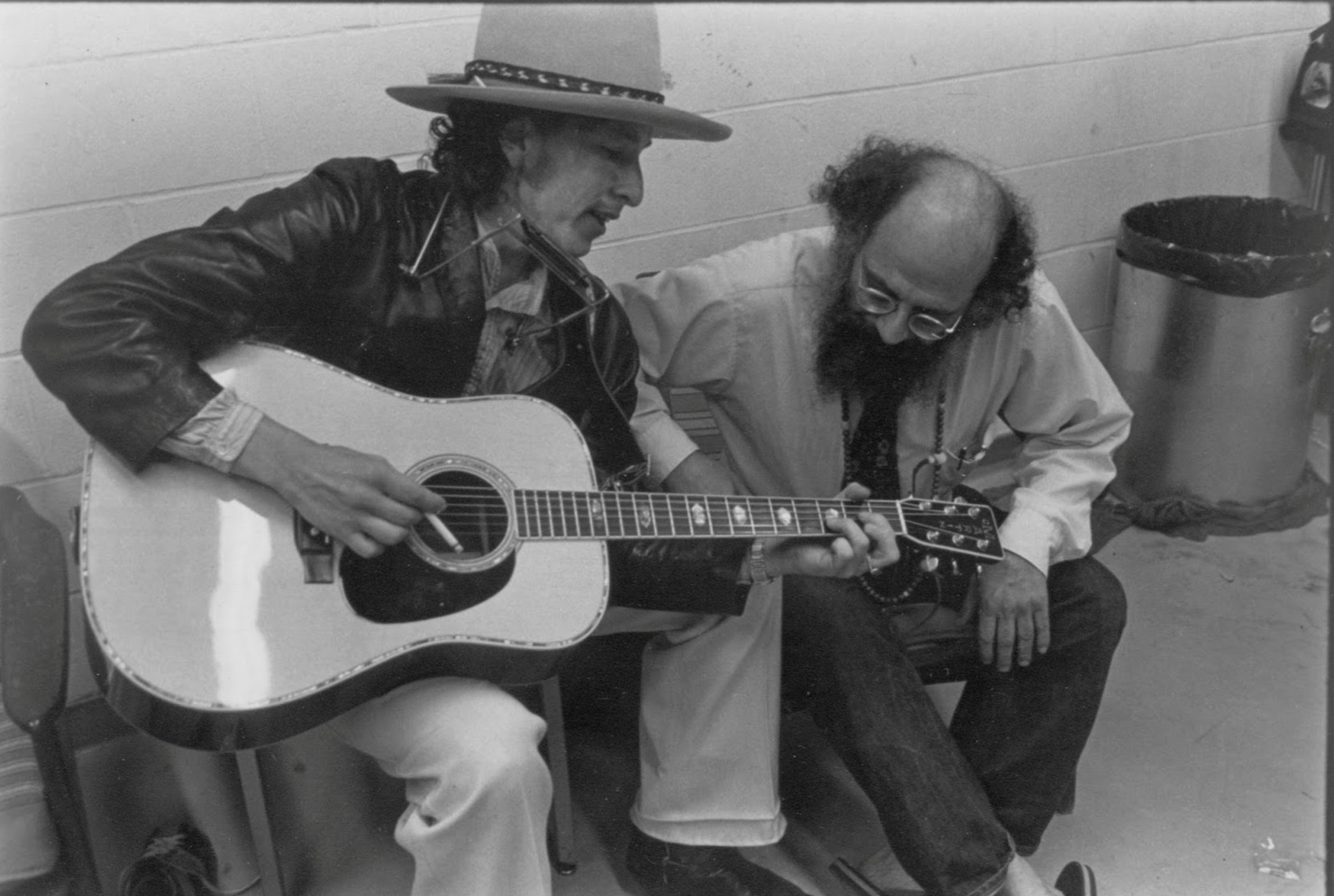

Dylan’s association with The Beats must be explored in order to comprehend the principles that informed his sixties output. “I Shall Be Released” was recorded in the infamous basement sessions of 1967, the undercurrents of the song may serve as a capsule of Dylan’s worldview at the time. His friendship with Allen Ginsberg (whom he met in 1961) is well known. It’s also evident Dylan venerated the work of other Beat giants like Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso. He went as far to say that Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues outright ‘blew his mind’ when he read it during the twilight of the ‘50s. Beat thought was clearly flowing through his veins during the decade that followed.

What did those writers believe? How does that relate to the song in question? The main intersection hinges on The Beat’s exploration of Eastern thought – namely, Buddhism. Kerouac would oscillate between Catholicism and Buddhism during his life – returning to Christianity long before his premature death in ‘69. For a while, during the fifties, Buddhism seemed to be the antidote to the inherent pains that he felt pervaded existence. For Kerouac, the dharma cut through the dreamlike nature of existence and gave him a sense of clarity. He wrote to his confidant, Ginsberg, in 1954 – ‘‘I always did suspect that life was a dream, now I am assured by the most brilliant man who ever lived (The Buddha) that it is indeed so.”

Kerouac built on this conception of the ‘flesh’ prison when he relayed to Escapade Magazine: ‘‘Life is nothing but a short vague dream encompassed round by flesh and tears.”

This may sound dreary, miserable, and frankly alien to many in the western world. To participate in capitalism, it’s integral that we identify explicitly with the self. Notions of individualism, progress, commerce and legacy are all entwined with the conviction of a fixed ‘self.’ We work, we contribute, accumulate and die. We meet our death hoping our name and achievements continue on; giving a fleeting sense of life beyond our end. Buddhists contend that the realisation of ‘no-self’ is, in fact, liberation. The clinging to the self is the prison that many find themselves in.

These are some of the ‘thought processes’ that Dylan was exposed to through his association with The Beat movement. His lyrics in “I Shall Be Released” evoke the dreamlike nature of existence and an unfixed self:

“Yet I swear I see my reflection

Some place so high above this wall.”

A reflection is ephemeral and intangible; not a ‘subject’ in itself. Reflections are devoid of substance, a mirage. It’s unclear where the narrator finds themselves. Are they a projection in the sky? Are they free? There’s a sense that they want to be disembodied from the physical space they describe, perhaps the vessel they were born into.

“Standing next to me in this lonely crowd,

Is a man who swears he’s not to blame.”

The contradiction of “lonely crowd” might indicate that when wrapped up in the conceit of the self, we make ourselves islands – becoming inherently isolated from one another. Rejecting blame does feed into the incarceration narrative, but, in an existential reading – it speaks to the sentiment that none of us are to blame for being here. Nobody asked, consented, but we must navigate suffering (and beauty) regardless.

Other Dylan pieces from this era further crystalise the links between the songwriter, The Beats, and the metaphysical reading of “I Shall Be Released.” In the opening stanza of “Visions of Johanna” (Kerouac had published his novel, Visions of Gerard, three years earlier) Dylan espouses: “We sit here stranded, though we’re all doin’ our best to deny it.” Again, he illuminates a loneliness inherent to the human condition. There’s a sense of isolation, entrapment, one that the song’s subjects can only combat with denial.

Released the year before Visions, the resounding “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (Kerouac published a novella, The Subterraneans, in 1958) manages to surmise the conceit of self, pursuits and life’s entire arrangement:

“Ah – get born, keep warm, short pants

Get dressed, get blessed

Try to be a success

Please her, please him, buy gifts

Don’t steal, don’t lift

Twenty years of schoolin’

And they put you on the day shift.”

Stumbling into birth, trying to be ‘somebody.’ Acquiescing to societal expectations, pleasing others, materialism. All must be endured before ending up in an unfulfilling job, one you’re chained to for the remainder of your healthy life. It’s all laid out.

It’s no coincidence that both of these songs are linked to Kerouac’s work. It’s testament to the synergies of the beliefs that The Beats and Dylan held. “I Shall Be Released” speaks to the same truth, or, perceived truth: Enduring the life we’re thrown into entails demoralisation, suffering. Once released from the flesh that binds us to this false sense of self, we might know freedom.

It would be negligent to examine the song without returning to The Band’s version. Richard Manuel’s ethereal voice motors the cover. Unfortunately, his angelic register hid latent demons. Manuel was dogged by the twin phantoms of depression and substance abuse for the majority of his adult life. In spite of his struggles, he played a pivotal part in producing art that stands the test of time. He gave joy to countless people by sharing his gift.

Despairingly, Manuel committed suicide in 1986. Rick Danko, bassist and another integral voice in The Band, played a rendition of “I Shall Be Released” at his friend’s funeral. It’s clear he read the song in the same way. He wanted Richard to return to that shining light, to be ‘released’ from the form that he often found so painful – to find a peace he couldn’t seem to uncover in this life.

It’s just another indicator of Dylan’s magnitude that the song could be interpreted in a myriad of ways by those that covered it, were moved by it, and penned discourse around it.

Whist an existential reading of the song may feel like an indictment of life, returning to the wellspring from which Dylan drew influence combats this notion.

The Metta Prayer is a Buddhist hallmark, designed to generate compassion for oneself and all beings by illuminating our commonality. We’re thrown into this life, without choosing, and therefore – we are, all of us, the same. “May all beings be happy. May all beings be well. May all beings be at peace.”

Hopefully, we find ‘release’ whilst still in the workings of the life we’ve emerged into. Perhaps release via the knowing smile of a friend, a ripple of feeling to music, or the savouring of a coffee as we make it through the day-shift.

— —

Cameron Tricker is a writer that is lucky to hail from the same town as Thomas Paine. His prose writing was shortlisted for Bloomsbury’s Writers & Artists Working-Class Writers Prize, 2024.

— —

— — — —

Connect to Bob Dylan on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© courtesy of the National Archives

:: Stream Bob Dylan ::

© courtesy of the National Archives

© courtesy of the National Archives