Nostalgia Tracks is Atwood Magazine’s column dedicated to the power of memory in music, diving into the songs that shape who we are and remind us of where we’ve been. At once personal and universal, these essays explore how certain tracks continue to resonate with us across time, bridging the past and present while tracing the threads of identity and culture that shape our lives.

•• •• •• ••

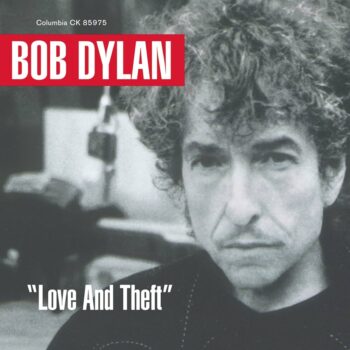

From his 2001 album ‘Love and Theft,’ “Mississippi” stands as one of Bob Dylan’s most seminal works, full of well-honed wistfulness and cultural quotation.

•• ••

Stream: “Mississippi” – Bob Dylan

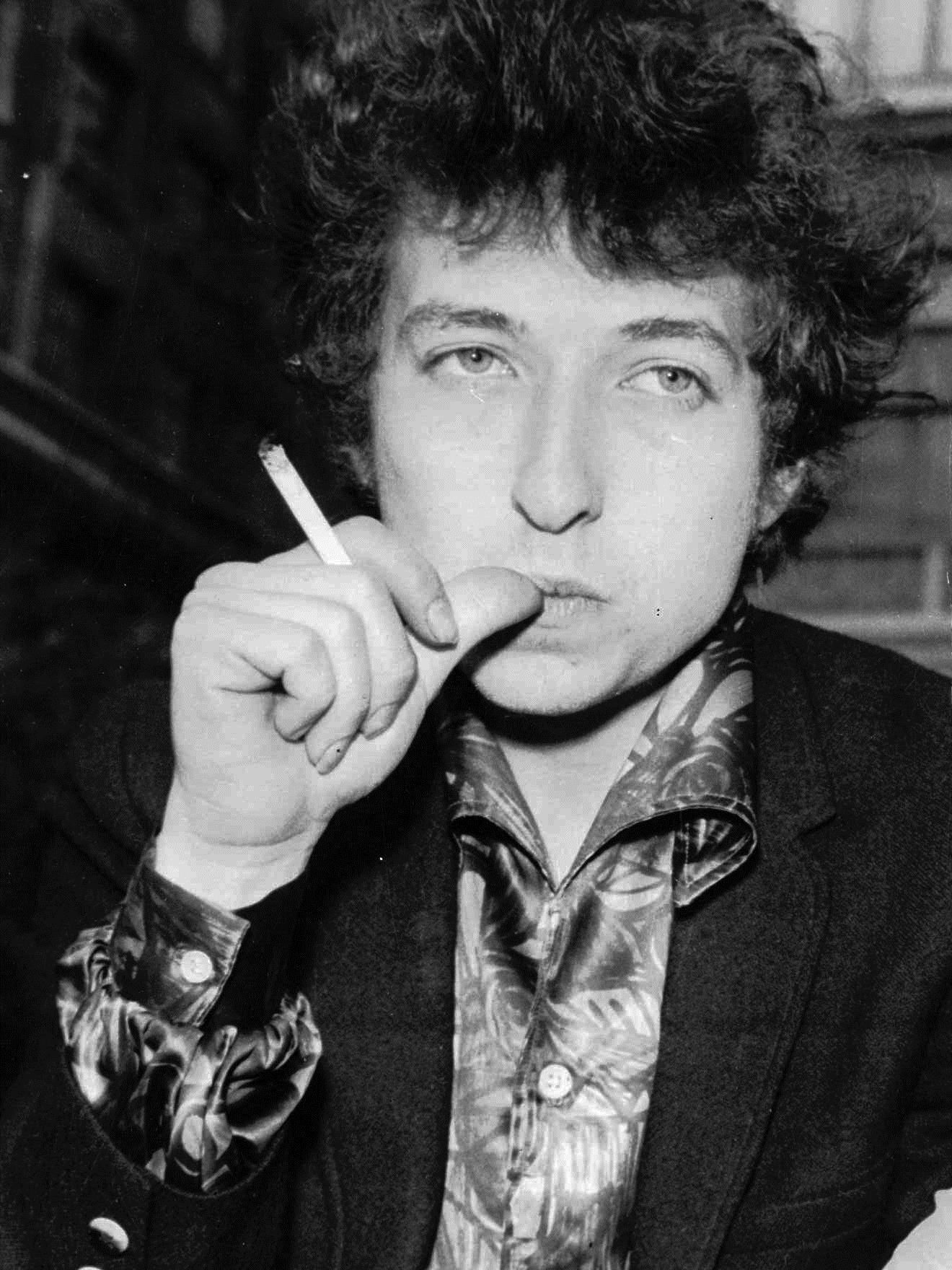

At age 84, Bob Dylan is a man who has been a lot of things and gone by a lot of names: Poet, prophet, Nobel Laureate, painter, ringleader, Judas, Jack Fate.

Above all, though, he’s the ultimate scavenger.

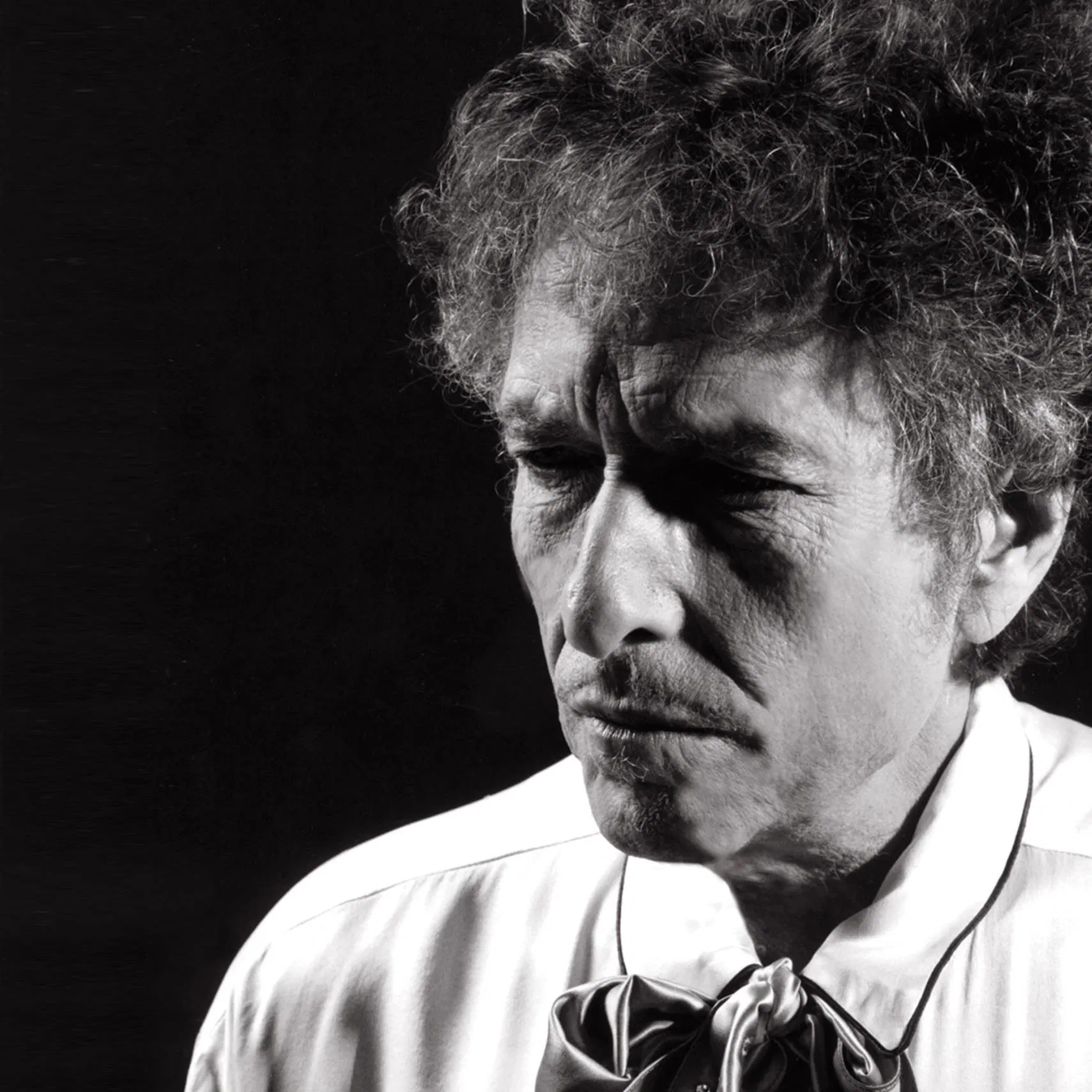

To scroll through his Instagram feed is to avalanche oneself in curated chaos: Old movies, a clip of “Hot for Teacher,” and recently an AI-read clip of Aaron Burr’s Art of Survival (I’m picturing a very chaotic YouTube watch history – maybe the stars really ARE just like us!). He offers no commentary on the videos, just these breadcrumbs. In a post-Taylor Swift world, it’s like he’s leaving a trail and we get to decide if it leads to a new record, a second memoir, or just a beautiful dead end.

You’d be forgiven for calling it archiving or homage. What I think it really is, though, is the byproduct of a mind in a constant state of reinvention. I’ve always been taken by the way Dylan excavates and reshapes culture in his music. It’s not just a nod, but an act in communion with those he borrows from. This scavenger’s approach to songwriting is what makes tracks like “Mississippi” from his 2001 album Love and Theft a colossus in his discography. It’s a true tapestry of a song that combines borrowed feelings, chain-gang field recordings, Shakespeare, a Yakuza memoir, Johnny Cash, and the Bible. For my money, it’s up there with “Tangled Up in Blue” and “‘Cross the Green Mountain” as some of his finest storytelling. (I know a lot of people say this about a lot of his songs. They’re usually right.)

Dylan is hardly the first to sing about Mississippi. Many others before him and since have invoked the state as a shorthand for their longing or grief or desire – Bobbie Gentry, Jesse Winchester, Loretta Lynn, Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, and many more. In Dylan’s “Mississippi,” the pastoral tableau of the American South meets the weariness of the new millennium. It’s expressive honesty from a man who has shrouded his life in mystery since he was a teenager.

He first recorded the song in 1997, during the Time Out of Mind sessions with Daniel Lanois. Lanois offered drums that Dylan later groused about (somewhat theatrically) as an “Afro-polyrhythm” misstep that was ill-suited for his knifelike lyrics. Oy! The outtakes, later released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs, show interpretations of the track that are beautiful but tentative.

“I’ve been criticised for not putting my best songs on certain albums,” Dylan noted later, “but it is because I consider that the song isn’t ready yet… We had that on the Time Out of Mind album. It wasn’t recorded very well but thank God, it never got out, so we recorded it again.”

Dylan would return to the song a few years later and by 2001, had re-recorded it for his next studio album, Love and Theft.

This version has a loose swing he surely felt better suited the lyrics, including an ascending bass line (rare for Dylan) that gives the song a surprising buoyancy. For many, this song and both albums associated with it were all a welcome return to the elemental songwriting of his early work. The ornate and synthy lab experiments of the ’80s (which, to be fair, are fun for what they are and spared very few aging ‘60s and ‘70s rock stars) had fallen fully away and left his voice standing.

The song is made up of twelve verses. They are separated into three sets, each ending with the chorus:

Only one thing I did wrong,

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

This line is a more-or-less direct lift from “O Rosie,” a traditional chain-gang work song. In the original, it’s a cry of exhaustion and rage, of men trapped by authority. Dylan turns the words into a broader reflection on his life, the condition of humanity, the state of the world. The narrative opens between city and country, with Dylan turning them into psychological realms of present and past:

City’s just a jungle,

more games to play,

Trapped in the heart of it,

trying to get away,

I was raised in the country,

I’ve been working in the town,

I been in trouble since

I set my suitcase down

The city is confining and hostile, the country a pastoral memory of freedom he’s carried since he left. In the third line, he’s likely nodding to Lead Belly’s song “Goodnight Irene”:

Sometimes I live in the country,

sometimes I live in the town

The song, naturally, operates on a small and grand scale. On the surface, it’s the story of a man confronting his regrets: love lost to time, some bad timing. But it also gives us feelings that reflect broader literary and cultural traditions. Take this line, for instance:

I know that fortune is waiting to be kind,

So give me your hand and say you’ll be mine

The latter line of the verse echoes Shakespeare’s Measure by Measure pretty much verbatim. His wholesale use of others’ words can feel like he’s assuring us they are, indeed, universal and always will be – someone has felt these things before, and they will continue to feel them after the last one of us is gone.

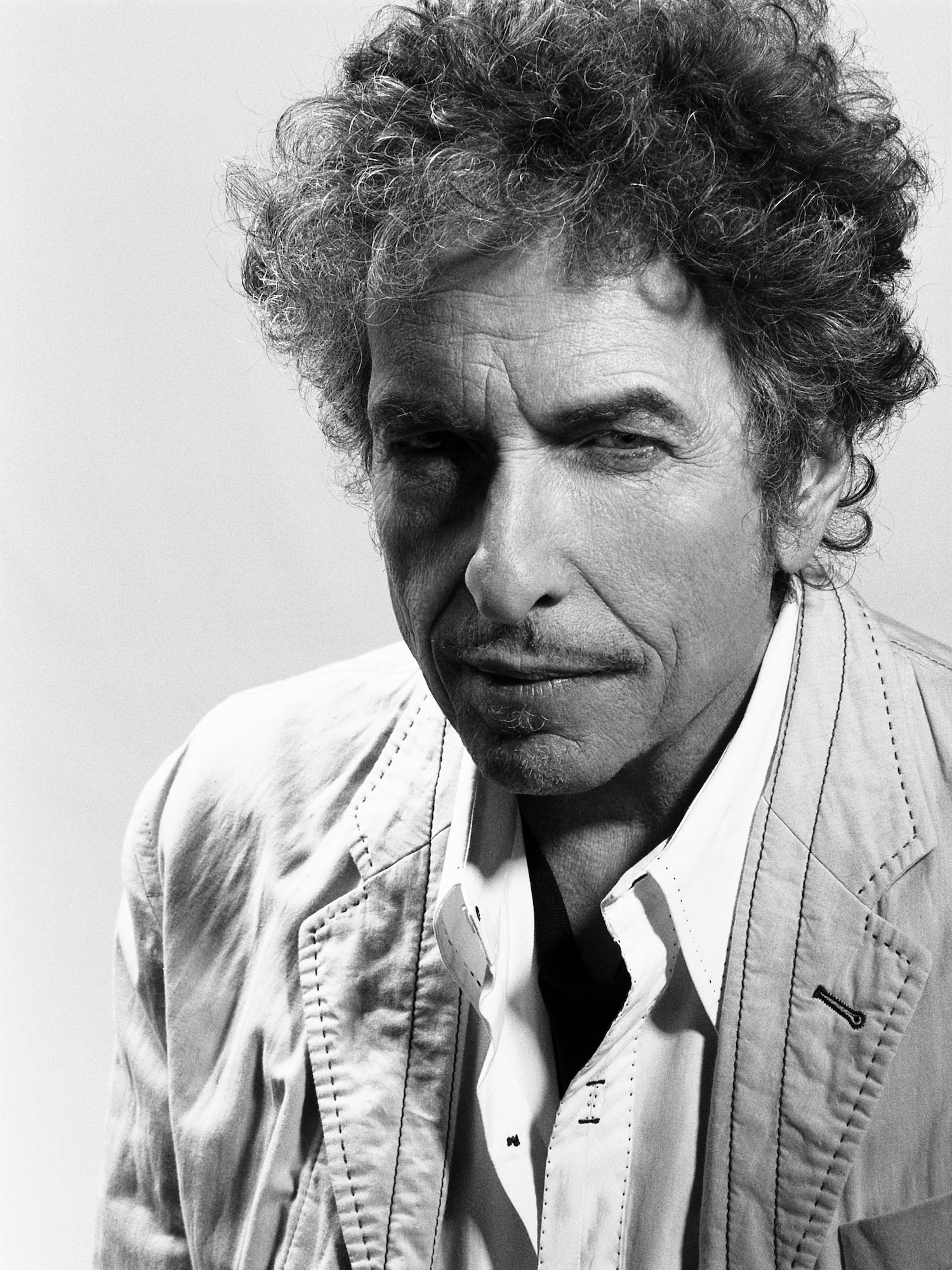

The process of borrowing (love and theft, if you will) is the heart of Bob Dylan’s genius, and part of the reason that “Mississippi” endures for many as a true masterwork.

In a culture where intellectual property has become a kind of sacred cow, Dylan doesn’t hide behind nostalgia. He’s not shy about resurrecting the past in lieu of worshipping it. He’s a walking, talking anachronism who knows that the best stories are the ones that are always being retold.

And every performance of “Mississippi” since its release has reshaped the meaning a little bit. He’s played it loud, soft, and loud again, proving, as always, that his old and new songs alike are gloriously and stubbornly alive.

A song this good, it turns out, can never truly be finished. It can only get better.

— —

:: connect with Bob Dylan here ::

— —

Stream: “Mississippi” – Bob Dylan

— — — —

Connect to Bob Dylan on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© courtesy of the artist

:: Stream Bob Dylan ::

© courtesy of the artist

© courtesy of the artist