In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Atwood Magazine has invited artists to participate in a series of essays reflecting on identity, music, culture, inclusion, and more.

•• •• •• ••

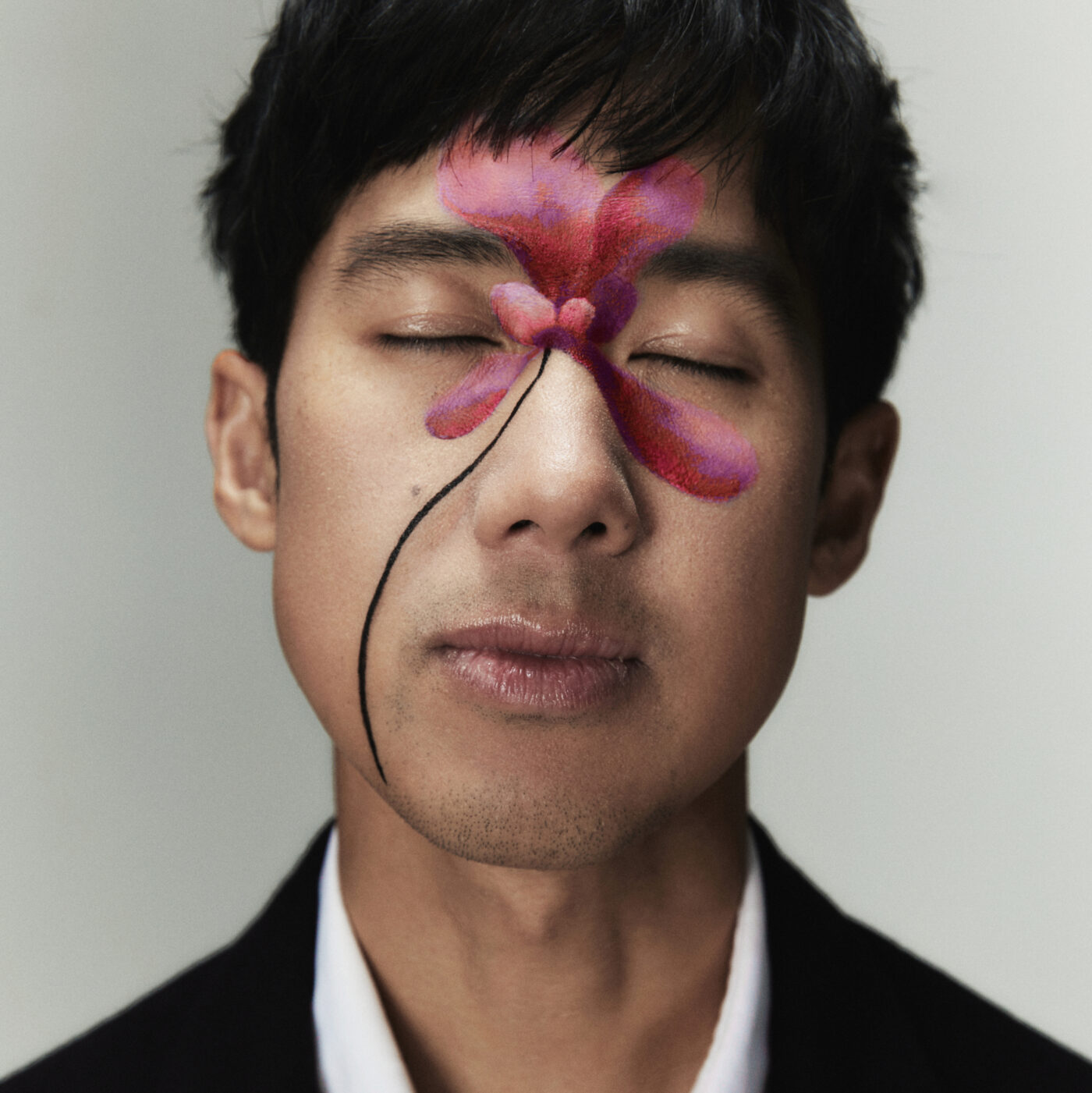

Today, New York City-based multi-disciplinary artist, musician, and writer John Tsung shares his essay, “Car Radios in Texas,” as a part of Atwood Magazine’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month series!

Tsung released his solo debut ‘Empire Postcards’ last year via Broken Stone Records. As an artist, he has collaborated extensively with Asian immigrants and Asian Americans in New York, across the US, and Asia. In addition to his solo albums, he has written for theater, film, and dance. His works have been featured in BOMB and Interview, and performed internationally. As a writer, he has covered the immigrant experience for Daily Beast and Eater, among other platforms. His forthcoming project is a music collaboration with a collective of young Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrant poets and musicians called GATSA!–chronicling their experiences as young Asian artists exploring new sounds and language.

Watch: “Pale Horses” – John Tsung

•• ••

“CAR RADIOS IN TEXAS”

by John Tsung

If you were blasting down I-45 in Houston sometime in the ’90s, you may have passed a Toyota minivan filled with Taiwanese kids, driven by a mom singing at the top of her lungs, going 80 in a 60 zone.

On any given blistering Saturday, we would have been completing an orbit between piano lessons, Buddhist temple, and our regular errands in Chinatown.

Little from the outside would distinguish us from other immigrant families on a weekend–brimming with aspirational brio and grit-your-teeth determination. But from inside, our minivan was an ark, piloted by enthusiastic explorers, amateur ethnomusicologists, my mom and my aunt, mapping this new world that we had crash landed in, song by song, band by band.

Being an American immigrant is to be a particular kind of American, one that comes with complicated blessings. You get to see this country with fresh eyes, in all of its terrifying splendor. The infinite aisles of fruit juice at Target. 31 flavors of ice cream whenever you want. Swimming pools the size of apartments back home. For me, America, and Texas, was amazing, confusing, and overwhelming all at once.

Mostly though, America felt like a house in which we were unexpected guests. We were very lucky–our neighbors were largely welcoming, and the kids at school friendly. But it felt like there was an unspoken code, a shorthand of belonging, and a comfortableness with being that, as an immigrant, you can get close to but never truly inhabit. Or worse, that the options were to try to assimilate and erase yourself, or to hold onto your culture and remain an outsider. As an adult, these are feelings one can name and even derive power from; as a kid, it just felt shitty.

But music was different. Music didn’t require you to choose an allegiance. Anyone with a car stereo could listen. And in listening, find your own way through this mystery of America.

If it was my Taiwanese-born and raised aunt driving, we’d most likely be listening to country music. I don’t know when she discovered Garth Brooks, but our cassette of “The Dance” had practically melted into the dashboard. Music didn’t need you to know all the words to sing along to “Friends in Low Places,” and Garth often took us to school and back. Sometimes he would be replaced by Gypsy Kings, if it was my NPR loving mom, or Madonna if my sister or cousins got the dial.

The hours that we spent in that minivan was an education on American culture for me.

From country, I learned about Texas swing. From Texas Swing, zydeco, and zydeco to norteño. Music showed me a way to understand my adopted homeland. Note by note, it mapped out a different topography and history of this land, one that is tangled and intertwined and appropriated and reflected across cultures and time. I learned that my violin can also be a fiddle. That my mom’s beat up nylon guitar could help me talk without talking. That the manager of the local guitar store cared less about where you were from and what you looked like than if you could play a good line–and would tell you stories behind the autographed Telecaster guitars if you stuck around.

Gradually, I found bands that I fell in love with, that were personal, and that felt like mine. Artists like Los Lobos, Living Colour, and Arto Lindsay. Artists who were bold and loud and brilliant, who defied expectations and crossed genres, who brought their respective culture to music in a way that seemed to me to represent all of who they were, and who did so without self-consciousness.

Today, we are living in a world where boundaries are more fluid than ever, where the most streamed band sings in Korean, where Rosalia and Blackpink top the charts, and Mitski and Japanese Breakfast are household names. In many ways, as artists, we are more free to do what we want. But in other ways, there is sometimes still the expectation, especially as an Asian American artist, that you either color within the genre lines or namecheck the most familiar aspects of your culture.

In an interview for my last album, Empire Postcards, which was drawn from oral histories of Asian immigrants, I was asked, with well intention, whether or not I had considered writing more songs in a Cantopop style, in reference to the Cantonese pop genre popular in the ’80s and ’90s from Hong Kong. In another interview, someone off-handedly said, “This album wasn’t what I expected when I heard that these were Asian stories.”

I was once standing in Waterloo Records in Austin, after my first SXSW show, holding a copy of “La Pistola y El Corazó,” by Los Lobos, their Spanish language tribute to Mariachi/Tejano music. Next to me was an old-timer with a long gray beard, rainbow colored suspenders, shitkicker boots, and a classic Sun Records T. Looking over my shoulder, nodding with approval, he said with a pitch perfect Texas twang, with no qualifiers, “now that is a great fucking album.”

I hope that, as we write our songs, sing of where we’re from, and bring all of ourselves, that we continue to expand what American music can be and what stories we tell. A world where Asian Americans, and all artists who stand across two cultures, don’t have to choose which side of us we show. In Toni Morrison’s words, “to carve out a world both culture specific and race-free.”

A world where the highest compliment is that this “a great fucking album.” Full stop. – John Tsung

— —

:: connect with John Tsung here ::

— — — —

Connect to John Tsung on

Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© James Bee

:: Stream John Tsung ::

© James Bee

© James Bee