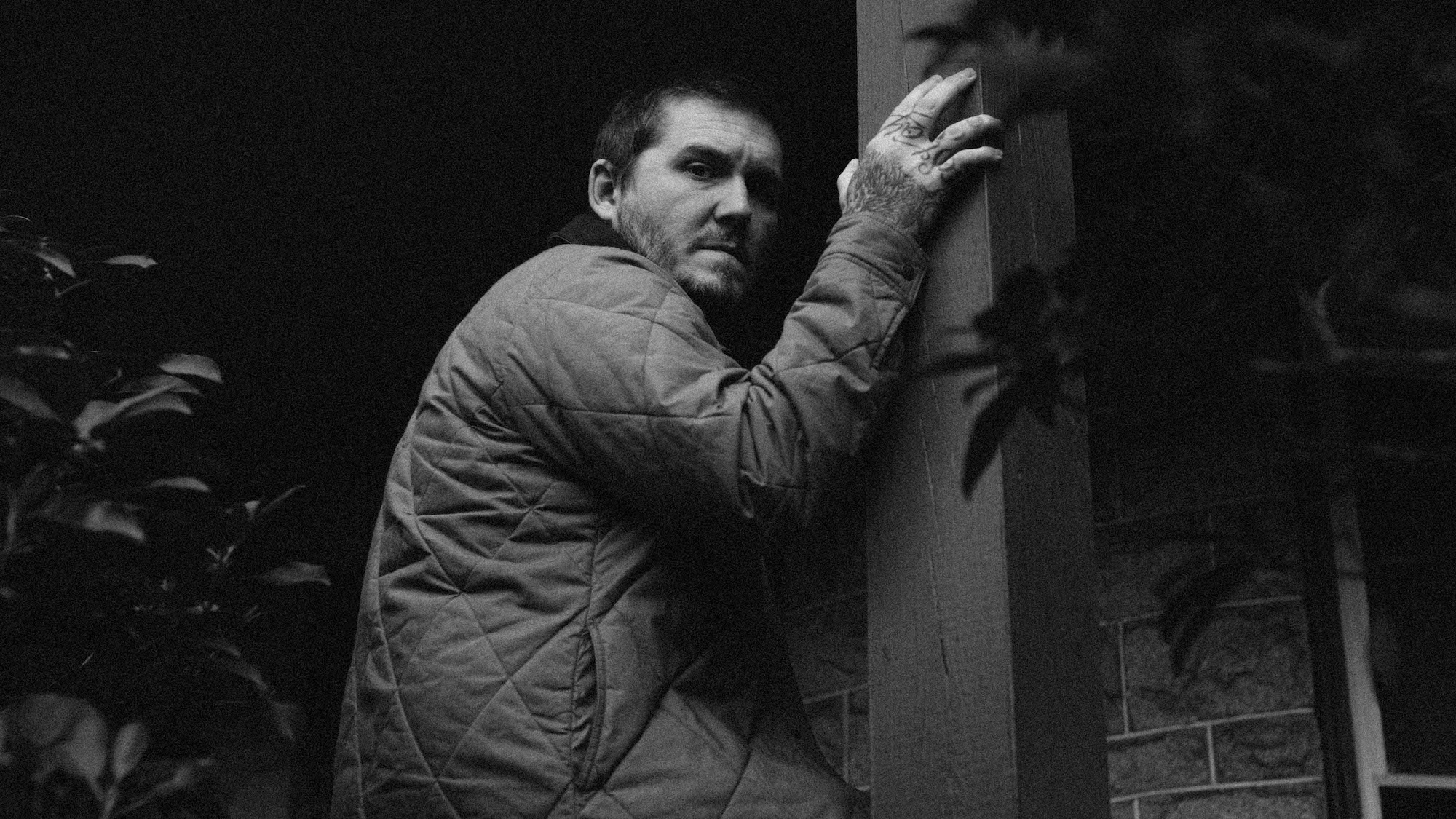

Since Americana isn’t a single sound but an amalgamation of American music, Brian Fallon’s ‘Local Honey’ is the embodiment of the genre.

Stream: ‘Local Honey’ – Brian Fallon

Brian Fallon always wanted to be a folk singer. Don’t take my word for it; the proof is in his music. Go back and listen to any of his previous records — Cincinnati Rail Tie’s The American Music EP onwards — and you’ll see it’s always been kicking around beneath the surface of his sound. It just took turning 40, having a couple of kids, and slowing it all down to get him there.

“You can see I was fishing around, I was trying to figure it out. I was like ‘I like these folk songs but I’m not old enough to be a serious folk artist,’ and I didn’t feel world-wise enough to be writing songs like Bob Dylan or Neil Young so I was trying to figure out the landscape,” Fallon says. “Even through the Gaslight records there’s always those songs, like “Navesink Banks”, or “Red At Night” or “National Anthem” or “Blue Jeans and White T-Shirts” where you can see that I’m really trying to craft this songwriter thing and I never could let it go. I always wanted to do it.”

His new record, Local Honey, feels like this dream is finally being finalized, like the ice shattering and the tide beneath flowing to the surface. And for those who have followed Fallon’s nearly two-decade career, it also feels exactly where you thought he would end up.

From his punk roots in the Gaslight Anthem through the artsy detour that was The Horrible Crowes’ flawless Elsie to his two previous solo albums — Painkillers and Sleepwalkers — there’s been a maturing and mellowing happening in both song and songwriter: “ I’m not going to write about busting out of your job and burning down the highway because that’s not what I’m doing. I’m raising kids and trying to pay my taxes and thinking about how I educate my daughter not to subscribe to this mentality that men tell you what to do — she has to listen to herself. How do you write about and then be like ‘but right after that I’m going to burn down the highway and kick open the doors’. That doesn’t make sense — I’d feel so fake,” Fallon explains of his evolution.

But don’t mistake this sense of inevitably for one of ease: This mellowing of sound and soul wasn’t bought easily.

***

You don’t have to talk to Brian Fallon long to realize he’s an incredibly humble guy. “It might be the humility of realizing you’re an idiot,” he says only half-jokingly. Considering he’s written the 2008 instant indie classic The ’59 Sound and has Springsteen in his phone contacts, he’s quick to the futility of ego: “It’s just not going to get me anywhere though. I’ve had an equal amount of being grounded into mush in the ground too — it’s been a lot of ups and downs.”

It’s this earnest nature that has kept his fans alongside him throughout his changing career. “They stick around. I don’t know why necessarily it happens, but I can see it and they’re on it for the ride which is really cool.” For a lot of these fans — myself included — his albums are like a check-in from an old friend, a semi-annual letter letting you know what’s new and where life is heading.

Fallon’s albums also serve as somewhat of a guide map, a reassuring voice about what he and his fans are going through or what’s to come. His ability to pour his heart into his work and to so deeply explore divorce, heartbreak, growing up or losing it all and starting again resonates with his listeners. Local Honey continues this trend.

But his appeal is more than the feeling of being validated.

What makes Local Honey — and all his previous records — so enjoyable are the obvious variety in influences. Even as a folk singer, he’s as much Joe Strummer as Bob Dylan; just like during The Gaslight Anthem’s gasoline match of a swan song Get Hurt he was as much Leonard Cohen as he was Eddie Vedder.

A student of music, the depth and breadth of his listening is very clear to see. “There’s a wide range of music I listen to; like how did I get from Minor Threat to Whitney Houston? It’s because I never put anything out,” Fallon says before adding “You don’t get cool points for listening to Don Henley’s nineties collection but yo, “End Of Innocence” is a good song. I probably wouldn’t have written the melodies I wrote had I not been so conscious of melody by listening to records like that.”

Nothing was off-limits, even if it came at a cost: “I lost a girlfriend once because I wore a Grateful Dead shirt,” he says with a laugh. “When I was a teenager there were the older kids who were really good at BMX and they would bring like Operation Ivy and all these cool punk bands and I was into it. So one day I roll up in a Grateful Dead shirt, tie-dye, and there’s the girl I just recently started dating and she was like ‘yo, I can’t have that, I’m out.’”

He laughs. “I kept that shirt though.”

In practical terms, without Etta James’ records, we would never get The ’59 Sound’s soulful follow-up, American Slang. Local Honey extends this logic, showcasing Fallon as Americana embodied as he digests the ever-growing songbook of a nation, before adding to it with the taste still in his mouth.

The “indefinite hiatus” of The Gaslight Anthem hit Fallon — along with everyone else in the world with taste — really hard. “It was super scary. I remember sitting on the bus when we had the meeting and I just felt a cold chill. I was thinking to myself ‘I’ve got a kid, I’ve got a mortgage,’ at the time I was going through a divorce. I don’t know what to do but this is bad.”

While many think the breakup was his doing, he quickly dispels that myth: “I think people blame me a lot because they think I wanted to go solo, but there was no plan for that. Like this stopped and then I had to figure out what to do. I had to go find a record label, the whole bit. I didn’t know what I was going to do — I thought I was going back to construction.”

Even the experience of creating the Gaslight Anthem’s farewell record Get Hurt was a tough one for Fallon, with himself not in a great mental space and the band pulling in too many directions. “I never really achieved what I was trying to do with that record. I was in such a chaotic personal place that I couldn’t see past what was right in front of me. There’s things I wished I had done more because I wanted to push all the way where we’re like, “we’re going out to Pink Floyd terrority” just to see what would happen. I don’t think I pushed far enough.”

Add in some label pressure and the end result is an album that, while it may have many high points, at other moments feels incomplete. “That record is just pure frustration. It’s frustration with ourselves, I was frustrated with my life at the time — I was fresh out of a divorce. I was just frustrated. Angry isn’t even the word because if it was angry it would have been a different record, it was just pure and utter frustration.”

This sentiment was shared by the other members of Gaslight Anthem too. “We felt like we were dogs that were being kicked. Nothing was good enough anymore. The band was just beaten down at that point,” says Fallon.

Taking this beating in his stride, Fallon used his next solo albums to try on different sounds.

While both efforts are stellar in their own right, it’s clear from the first listen of Local Honey that Fallon has found the sound he began searching for on 2016’s Painkillers — and by his own admission he’d been slipping into Gaslight Anthem records all along. Now that he’s found his sound, he’s not looking back.Gone are the old ghosts that haunted his previous records. Retired too are the references to previous songs, the “treasure map” of influences Fallon leaves his most dedicated of listeners. Gone even is the cloud of regret and backwards-facing lyricism that seemed to be Fallon’s distinct viewpoint.

The Gaslight Anthem’s time has passed, but Fallon’s pride of those days hasn’t and he won’t let them be sullied by anything “We could have just been like ‘der-der-der-der-der, the ‘69 sound’ but you know what that would do though? It would destroy the goodwill that we’ve built over the years making good music that we’re proud of. I speak for all four of us: We feel really strongly and proud of the stuff we’ve done and we can’t ruin that.”

Out of all this, we get Local Honey. It’s a stripped-down, vulnerable collection of songs about fatherhood, giving up old habits and of being a good human in the 21st century.

While this bare sound may feel like a big break for Fallon, it’s not a surprise to him: “In a way it’s what I’ve always been looking for. I feel like I’ve been building this up for many years and I’ve just been scared to jump off the diving board. It’s something I’ve always wanted to do but it took me this long because I was afraid to just strip it all down. As soon as you do a record like this the microscope goes one hundred times more on the lyrics.”

Fortunately lyrics have always been a strong suit for Fallon, although the endearing “Vincent” is completely different from anything Fallon has ever done before; it’s a completely fictional song. “I try to never be preachy in my music, so instead of writing it from that angle I was like “I don’t know what anyone should do, but I’ve got this character and I’ve been sitting with them for a month now and this is what they’ve decided to do.’” This storyteller approach is a clean break from Fallon’s heart-on-sleeve approach and yet, is no less personal. “It gives you freedom to express how you feel without getting on that holier than thou thing.”

Opening with a simple strummed acoustic guitar and quickly followed by Fallon’s trademark grizzle, it’ll bring tears to your eyes quickly.

I would fly solo

To the rodeo dance

Cover my bruises

In a Maybelline Mask

I’d wait till he passed out

He did it most nights

I’d go to meet Vincent

To come back to life

And nobody knew

But inside I would break

There always this screaming

In between, I’d just wait

One night I supposed

Finally drove me insane

I stabbed him once

And then I stabbed him again

This general tone of sadness pervades the album. It’s by design. While Fallon’s albums have never been the happiest, working with the legendary sad-boy Peter Katis (The National, Frightened Rabbit), seems like a match made in heaven. “He creates these worlds. I told him ‘we got to create landscapes and sounds’ and he said ‘that’s what I do, let’s do it. You sing, I’ll do that.’ And that’s what we did. I would go in and play piano or guitar and then we would just start building all these different things and sounds together,” says Fallon. “Peter is more like this is your expression, you’re a grown up artist and you know what you want to do so you do that and I’ll make it sound good.”

Described by Fallon as a sibling of Elsie, Katis helps bring this sadness to the forefront of Local Honey. A big fan of musicals, Fallon describes the play-like nature of his music that Katis helps accentuate. “Both Elsie and Local Honey sort of did the same thing of letting the lyrics tell the story and not being afraid to slow things down. I always thought of the instruments for this record as the scenery, and same with Elsie. The instruments and the notes that we chose in the music we all about setting the scene, and then the lyrics were the thing guiding you through. The lyrics are the actors and the music are the set.”

With Fallon’s career shifting from the high-octane fires of youth to the sobering, thoughtful wonderings of middle-age, he is reminded of another great Americana performer: “You know who I think did it great? Tom Waits. He was like ‘I’m the drunk piano player, I’m a vagabond, a sailor,’ but then he sobered up, got married and was like ‘I can’t be that guy anymore. I’m a sober weirdo and I want to write about circuses and banging on pots and pans because that’s who I am.’ And then he hard-cut the line between that stuff.”

While Fallon’s shift may not be as dramatic as Waits’, the message at the core of it is identical: “You have to just be who you are at the moment you are at.”

— —

:: stream/purchase Local Honey here ::

— — — —

Connect to Brian Fallon on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Kelsey Hunter Ayres

:: Stream Brian Fallon ::