Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon’s sophomore album is an aching, vivid portrait of a person in phases.

Stream: ‘Wake Me Up When It’s Over’ – Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon

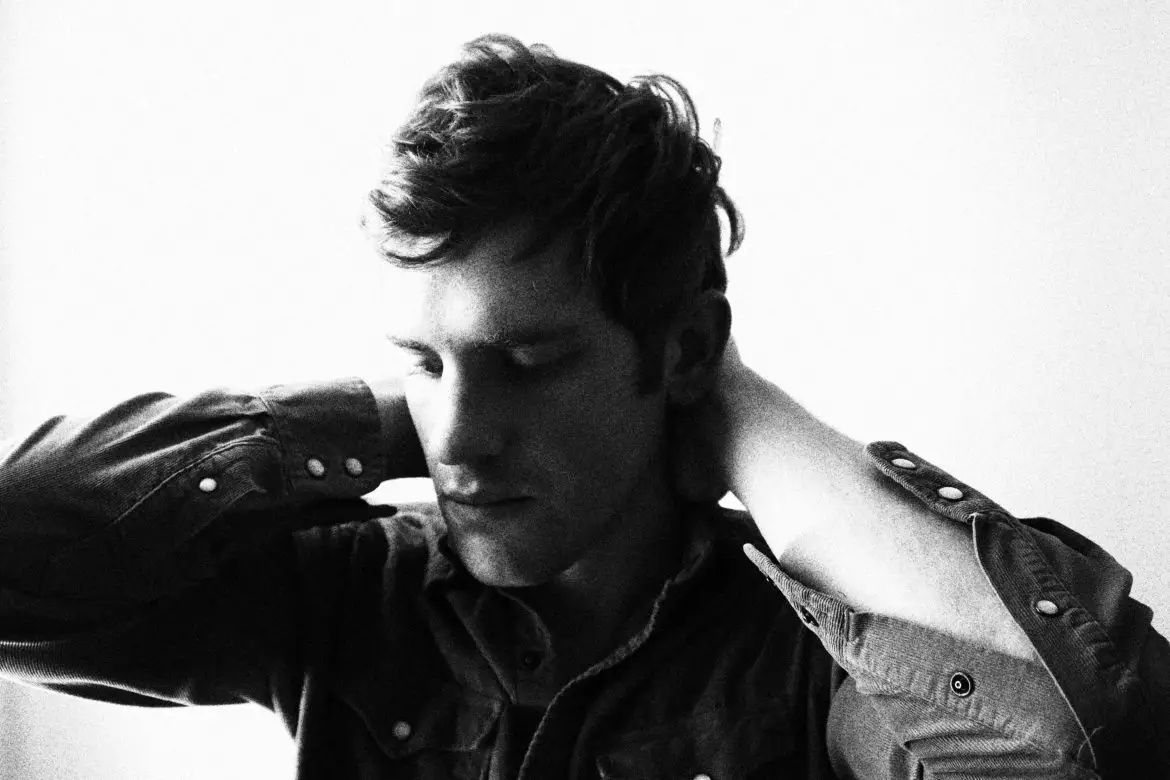

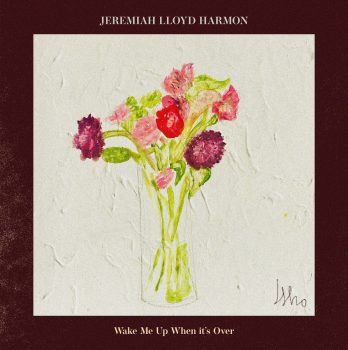

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon is the type of musician who feels classic from the moment you hear him sing. Despite being obviously inspired by artists like Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell, Harmon’s work is anything but pastiche. Like his predecessors, he possesses a keen and poetic eye for stories; his songs are vivid and surprising, expanding moments into worlds. His arresting tenor carries each song as if on wings, from near whispers to soaring heights. Harmon’s catalogue mirrors his wide instrumental and vocal abilities — though his earliest released music is influenced by jazz and R&B, his newest record Wake Me Up When It’s Over (out June 11, 2021) is a masterpiece of subtle folk.

After the recording of his follow-up to 2020’s Namesake was put on hold due to COVID, Harmon went home to Baltimore to record. “I feel like this is the folk album I always wanted to write,” he says. Quarantine, and a quiet need to exorcise past versions of himself, gave him the freedom to do so. Wake Me Up When It’s Over, which was written, recorded, and produced by Harmon himself, is a collection of songs that find him moving through different phases of his life.

After the recording of his follow-up to 2020’s Namesake was put on hold due to COVID, Harmon went home to Baltimore to record. “I feel like this is the folk album I always wanted to write,” he says. Quarantine, and a quiet need to exorcise past versions of himself, gave him the freedom to do so. Wake Me Up When It’s Over, which was written, recorded, and produced by Harmon himself, is a collection of songs that find him moving through different phases of his life.

Not wanting to deal with the rigmarole of LA show business, Harmon has stayed in his Baltimore home and volunteers at a farm down the street. Album opener “Mama, I Don’t Wanna Go to Nashville” finds Harmon wrestling with the pressures of seeking fame after his stint on American Idol, while “Alaska” (which also once appeared on a demos record) details off-the-grid months spent on a fishing boat where he came out to himself as gay for the first time.

I want to go to Alaska

I want to see the Milky Way sky

I want to jump into that water

I want to learn how to be afraid for a while

For a record whose only instrumentation is an acoustic guitar, it contains a stunning amount of variety. Harmon is a master at the subtly unexpected, slipping in chords and melodies that flow seamlessly while also taking a song to someplace new. Wake Me Up When It’s Over is a finely drawn series of portraits, each examining a brief but potent moment in time.

The album’s cover is a painting of Harmon’s, whose paintings typically favor the abstract — while working on his still life skills, Harmon was struck by the idea that the prettiest flowers are always cut first. But it’s the ones who stay behind that get the most sun.

— —

:: stream/purchase Wake Me Up When It’s Over here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH JEREMIAH LLOYD HARMON

I was reading the interview you did with Billboard last year about the “second album” – but this doesn’t seem like the same album.

Maybe you just answered this question, but this album is so hushed and intimate compared to Namesake. What led you to this? You said this is the folk album you always wanted to write.

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I felt like some of these songs were songs that I needed to publish before I die, not to be super morbid. I write a lot of songs, and some of them survive the passing of time and most of them don’t. There were a couple tunes on this record that kept coming back to me years after having written them and it just felt like I should give them a proper release. They had been released on demo albums on Bandcamp in the past and the response was really positive for those songs. They’re deeply personal songs about some pretty transformative periods of my young adult life, and so this felt like a swan song to a previous version of myself. Writing these songs was a form of closure and releasing them made me feel like, “Okay, I can really move on from that season in my life.”

“Alaska” was on the Souvenirs demo record that you released a few years ago. Why did that one make the cut for this album?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: That one cuts deep for me. It was about this really transformative period of my life. I was deeply entrenched in the world of conservative Christianity before I wrote that, feeling numb and kind of being suffocated by that Christian bubble that I was living in. I decided to just drop out of school and go work in Alaska for like, five months, completely off grid. It gave me the first real opportunity to shut out the world around me and listen to myself a little bit. I came out to myself for the first time when I was in Alaska. When I came back home, I was a different person and I needed to document that. There was a lot of existential angst happening during that time, and that song is about one of the most defining experiences that I’ve had so far in my personal life.

I know from hearing you talk on American Idol and your song “Almost Heaven” that spirituality is a complicated thing for you. What’s the relationship between music and spirituality for you? You grew up singing in church, right?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: Yeah, I did. They feel inextricably bound, music and spirituality. Maybe I’m biased because I grew up in such a religious environment, but I think music is inherently spiritual. I guess my experience allows music to be spiritual without being religious, but it started off as very religious for me. It’s been my tool to navigate the changes in my life regarding my relationship to religion. I’m a pastor’s kid, which I’m sure you know if you followed my story, and it just comes with a whole thing I’ve been trying to grow out of. The way I grow personally is largely through music. The moments of realization that I have are in songs that I’ve written. And when I’m not contextualizing my life through music, I feel like I’m floating. I feel lost without that tool. It’s been my little sailboat through this ocean of consciousness [laughs] — like the unconscious is trying to swallow me constantly and music helps.

Chris Thile said something to me in an interview that's really stuck with me: that music is better at asking questions than answering them. From what you're saying, I get the sense that that's how it is for you. It's like posing questions to yourself.

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: Music gave me the freedom to ask questions for the first time. I was sort of surrounded by answers to life growing up; everything was figured out in a way. But I was still so confused and I had many questions. [Music] was a safe space for me to ask those questions. I really try to not be preachy in my music. I think that’s because I was under so much preaching growing up and I was like, “Why am I always being told what to do?” I probably have a hypersensitivity to that

Your music has gotten Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell comparisons, both of whom write from such seemingly personal places but also have created these amazing characters. You said your music is very personal, but I’m wondering: are you always the speaker in your songs? Where is the line for you?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I think generally what I do is take real life circumstances and real life me and exaggerate them a little bit and fictionalize them slightly, so that it feels separate enough for me to not be so — I don’t know. I guess you can never be objective about your own work, but it feels like that level of separation gives me some objectivity. I do feel like especially when I’m performing live, I kind of channel this performer person. Maybe that’s a little bit of the same character that I take on when I’m writing. I’m kind of pretending to be a future version of myself. Or I’m almost pretending to be one of these people that I admire. I think a lot of songwriters do that. Personally, I don’t know exactly what the character is, but it does feel like some level of channeling and stepping into a different role.

Are there non-musical writers you carry with you as you’re writing your own music?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: Khalil Gibran is a huge inspiration for me. He wrote “The Prophet” and a lot of other short stories and poems. His stuff touches me on such a soul level. I feel so seen by his work; it’s very mystical and romantic. I think part of the reason I like him so much is that he uses a similar model to a lot of passages in scripture. He’ll speak in parables and he’ll have the same sort of poetic rhythm and meter as like, Book of Proverbs or Psalms, or something like that. I’ve got this book of collected works by Kahlil Gibran and it’s kind of like my Bible.

You’re a painter as well. How does visual art and music intersect for you? How does one inform the other?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I don’t know exactly if it comes from the same place or what, but actually, I feel a struggle to allow those two things to live in the same world. I did paint the cover art for this album. I was really trying to practice my fine art skills [laughs]. It’s just this normal picture of some flowers that I had painted. The story behind that is that it’s become this meditation for me about cutting flowers, the prettiest ones. Then they slowly die, and it’s just very sad and romantic [laughs]. That might be the closest that the visual and sonic arts have come together for me. I have a lot of paintings that feel like they come from a different place, and I wouldn’t know how to marry my music and visual art.

You mention a vase of flowers several times in “Consider Me the Loser.” Is that coincidental or...

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: “So I breathe a sigh / take a little time / to observe a vase of flowers on the table / how they slowly die / in a fashion that reminds me / that winning only means they cut you sooner / and if that’s really so / consider me the loser.” I would rather be the flower that’s not been cut, and is living its best life in the sun, than be some trophy on somebody’s table. That whole thing was a metaphor for the [music] industry for me, and having gone through this really bizarre reality television experience, and then having all these expectations to jump into the industry and get signed. I was planning on moving to Nashville after all that, and then this huge blessing in disguise happened. I wasn’t really prepared to leave my home and I started volunteering on a farm down the street. It really was the time and space that I needed to process the last two years.

Your earliest released music has a big jazz influence – can you talk about genre fluidity and where you see your music going in the future?

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I’ve always been a little self-conscious about not fitting into one particular box. Not just musically, but when I was growing up too. I moved so often that I never found my clique or whatever, my people. It was like, “Oh, I’ll be like them for a little bit and see if I feel at home or accepted.” Then I move two years later and I shape shift again. That became a part of my personality and that still lives in my music. It’s hard for me to live in one place for very long; it’s hard for me to play the same kind of music for very long. I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s wanderlust. What different places could I go musically? How can I reinvent myself again and take on different characters? I feel like some of it is this playful, childlike spirit of pretending. But there is a very real aspect of searching for myself in the music. I’m searching for a sense of self and a center. I think you kind of see me going through these phases, looking for what feels most true.

That’s a process that is always evolving for me. I do one thing and it feels good and then it’s done. Then I’m like, “Well, on to the next thing, that doesn’t feel like me anymore. Where am I again? I have to go find myself in this different costume or something.” I think we all do that in different ways. Not to pretend like I know everything about human nature, but I think we’re all looking for ourselves in different ways. We live in these outfits that make us feel like ourselves, that make us feel affirmed and seen and comfortable. I don’t know if that answers your question, but it’s something that I’m trying to make peace with and not be so self-conscious about. I think that’s why I look up to artists like Joni Mitchell. She constantly reinvented herself. It’s artists like her that make me feel affirmed in my own process.

Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I wanted it to feel centered around this idea of sleeping or escaping through the unconscious. It just sort of appeared as a common thread in the songs that I’d written. I never write with an idea that I’ve pre-determined. It always comes after the fact. It’s the same with the albums. I write a bunch of songs, and then I see what fits together and what feels like a theme. To me, this album was about escaping and finding solitude, and yeah, an absence. That’s demonstrated through different stories of encounters with other people and different kinds of parables of escapism, tales of loneliness. This whole last year was like, if I could be unconscious for like a year and come back, that would be preferred [laughs]. I think a lot of people felt that way. For me, writing this album was a form of escape but also a way of confronting some of the harsh realities, with the music as a sort of buffer. Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon: I want people to feel like they can apply these songs to their personal lives and feel like they have a space to escape to themselves. That’s what the album provided for me: a safe space where I can fantasize about different things and be free to explore and express myself. I hope that people can listen to this album and find their own version of that space for themselves. — — — —

I know that this isn’t a concept album, but I feel like there’s a thematic thread of absence and return on this record. Can you expand on that?

What is the ultimate sentiment behind Wake Me Up When It’s Over?

Connect to Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon on

Facebook, Twitter, InstagramDiscover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon

:: Stream Jeremiah Lloyd Harmon ::