Peter Rowan speaks to Atwood Magazine about his tutelage under Bill Monroe, his solo career and collaborations with other artists, and his Fall 2021 tour with the Free Mexican Airforce.

by guest writer Mike Fiorito

Stream: “Vulture Peak” – Peter Rowan

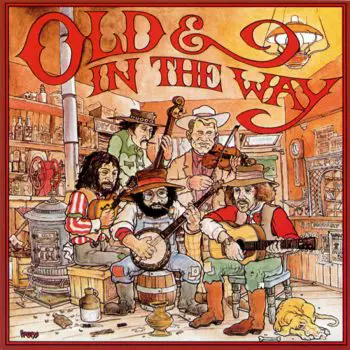

I’ve been a fan of Peter Rowan since listening to the Old & In the Way album when I was in my teens in the seventies. As a kid from Queens, NYC, I didn’t grow up listening to bluegrass and country. Old & In the Way exposed my generation, especially people from the cities to the bluegrass music of Bill Monroe, The Stanley Brothers, Roy Acuff, and others. Old & In the Way was so explosive, so full of joy and energy it appeared to come screaming out of the sky on a chariot of fire. Featuring Jerry Garcia on banjo playing, Vassar Clements on fiddle, David Grisman on mandolin, the Old & In the Way album blasted open a portal to another universe for me and many others.

It’s hard not to tap your foot to the quicksilver speed of the instrumentals and sing along with the otherworldly angelic harmonies on Old & In the Way. Like all American music, bluegrass is a composite of the many cultures that came together on American soil. Bluegrass reaches far back beyond Bill Monroe, into what Greil Marcus called that “weird old America, a playground of God, Satan, tricksters, Puritans, confidence men, illuminati, braggarts, preachers, anonymous poets of all stripes.”

Since hearing Old & In the Way, I’ve begun a musical journey that’s never really ended.

If Bill Monroe is considered the Father of Bluegrass, Peter Rowan is its international ambassador.

And although there is a plumbline of bluegrass spanning over the six decades of his career, Rowan has continued to reinvent himself. He’s composed and recorded reggae, rock, Hawaiian, psychedelic, and country music. And he’s collaborated and performed with the best musicians of our time, including Clarence White, Buell Neidlinger, Ricky Skaggs, Mike Auldridge, David Grisman, Jerry Garcia, Tony Rice, Flaco Jimenez, Vassar Clements and many others. Rowen’s extensive discography reflects the incredible breadth of his career.

A Grammy award winner and a six-time Grammy nominee, Rowan plays guitar, mandolin, yodels, and sings. He has written too many great songs to mention. Some of my favorite songs are “Vulture Peak,” “While the Ocean Roars,” “On the Blue Horizon,” “Midnight Moonlight,” “Medicine Trail,” “Sweet Melinda,” “The Light in Carter Stanley’s Eyes” and “Panama Red.” A more comprehensive list can be found here.

Rowan doesn’t have a single bad album in his entire catalog, in my opinion. Some of my favorite Rowan albums are The Medicine Trail, The First Whippoorwill, Texican Badman, Yonder (with Jerry Douglas), and You Were There for Me (with Tony Rice), Dharma Blues and Carter Stanley’s Eyes.

Born in Wayland, Massachusetts to a musical family, Rowan learned to play guitar from his uncle. He spent his teenage years absorbing the sights and sounds of the Hillbilly Ranch, a legendary Country music nightclub in Boston frequented by acts like The Lilly Brothers and Tex Logan. In 1956 Peter Rowan formed his first band, the Cupids, while still in high school.

I had the honor of speaking with Rowan in early April 2021.

Let me give a little back story. I had interviewed Yungchen Lhamo, the international Tibetan singer who had performed and recorded with Rowan. When I asked her about how she’d met Rowan, she asked me if I would like to talk to him. Not wanting to sound too eager I meekly said yes. A few minutes later Yungchen texted me Rowan’s mobile number. He’s waiting for you to call.

I have to say that I was a little nervous. I’d long been a fan of bluegrass, but I wouldn’t say that I’m an expert. I’m moderately knowledgeable of the genre. My friend Greg Grady, who turned me onto his vast record collection in the nineties, knows a lot more than I do. Spending time with Greg was like getting a certificate in music listening. I went to jazz, folk and bluegrass music shows with Greg when he lived in New York City. His wall-to-wall collection was something to behold, as was his vast knowledge of who played with who, when, on what label and so on.

After arranging a time, Rowan and I spoke the next night.

It was magical to listen to the voice I’d heard sung in my head for nearly forty years speak softly on the phone line. Rowan was easy to talk to, funny and very smart.

“How did a kid from Wayland, Massachusetts get an audition with Bill Monroe?” I asked.

“There was a big bluegrass scene in Harvard Square starting in the fifties. And there were also pickers in the country, just outside the city. In about 1962, I met Joe Val (real name Valiante), who was passionate about bluegrass. Joe was the link between college kids and bluegrass lovers. Joe had met Tex Logan when Tex was a student at MIT. Tex was kind of a technical genius, but he also loved bluegrass and country music. Tex and Joe played at the Hillbilly Ranch, a legendary Country music nightclub in Boston. I spent my teenage years absorbing the sights and sounds of this scene.”

Tex could not pronounce Valiante’s Italian last name, thus introducing Joe onstage as Joe ”Val.”

Rowan explained that Joe and Tex were about fifteen years older; he was about sixteen at the time. Though he also played with his rock band, the Cupids, Rowan then turned his attention more to bluegrass.

“Tell me about Joe.”

“Joe was down to earth; he was a typewriter repairman. He searched out the essence of bluegrass. Joe became an emanation of Bill Monroe in mandolin and vocal style. Of course, he gave it his own lifeblood. In this circle of players was Bill Keith, who had played banjo with Monroe as a Bluegrass Boy on the Grand Ole Opry. Bill (Keith) lived in the Boston area and often got together with Jim Rooney, guitarist, singer, and music producer. They were both studying the origins of the ancient ballads and had a deep appreciation for string band music.”

Rowan said that the corridor of bluegrass music went from Boston to Pennsylvania, down Highway 81 (formerly Route 17) to West Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. From there, the circuit continued into Kentucky and Tennessee. For some reason, it skipped the thriving New York City folk scene. Val went on to play with the Charles River Valley Boys, a group formed in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the time, Keith and Rooney needed a mandolin player. Since Rowan had been playing around the scene, Val eventually asked him to take his place with Keith and Rooney. Afterwards, they toured for a while as Keith Rooney and Rowan.

With the folk revival in full swing, groups like Flatt and Scruggs immediately recognized the potential for a lucrative new audience in cities and on college campuses in the North, but Monroe was slower to respond. Under the influence of Ralph Rinzler, a young musician and folklorist from New Jersey who briefly became Monroe’s manager in 1963, Monroe gradually expanded his geographic reach beyond the traditional southern country music circuit. Rinzler co-wrote a lengthy profile with Mike Seeger in the influential folk music magazine Sing Out! that first publicly referred to Monroe as the Father of Bluegrass.

Intending to bring visibility to Monroe, Rinzler put a band together for Monroe that included Keith. As Rowan had played with Keith, Rowan was hired to sing lead and play guitar.

“We did a long weekend of gigs all over New England. During this time, Bill Monroe asked Bill (Keith) to help me. Bill Keith then invited me to (what they called back then) the DJ convention in Nashville. The event was just for musicians and DJs. There weren’t any fans there. The convention was very eye-opening for me. I met icons as they sat around and played. And I learned that, despite the formulaic Nashville style, there were a lot of jazz musicians in Nashville. With jazz and big band on the decline, musicians switched over to bluegrass and country. There were countless studio musicians in Nashville like Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland, Roy Huskey Jr., and guitarist Chet Atkins who were schooled in jazz. Keep in mind, people like Patsy Cline and Jim Reeves were jazz influenced singers. “

“Why did you leave Bill Monroe?” I asked.

“You have to remember I was about twenty-two; Bill (Monroe) was about fifty-five at the time. I could have just stayed and played with Bill. But first, Bill had problems paying sometimes. And – this was more important – I had to feel the fire in my own engine. I was bursting with songs and ideas. Let me also add that Bill was grooming his son, James, to be the lead singer. I didn’t want to stand in the wings. I wanted to stake out my own direction. The last show we did was at Whitey’s Lounge in Baltimore, which was also the first place we’d played together. Richard Greene on fiddle, James Monroe on bass. People said the music was so elevated, it felt like Bill was giving me a sendoff in a rocket. But Bill had his own arc, his own agenda. And he understood me.”

“What was one of the most important things you learned from Bill Monroe?”

“Everyone played to the time of Bill Monroe’s impeccable mandolin and stark tenor voice,” said Rowan.

After leaving Monroe, Rowan teamed up with Grisman to form Earth Opera, a psychedelic group that frequently opened for The Doors.

“What was it like leaving Bill Monroe to play in Earth Opera? You wrote all the songs. It was like, as you said, you had socked away a whole bunch of ideas and had them at the ready,” I said.

“I wrote all of the songs in Nashville. Then I showed them to Porter Wagoner. Wagoner had taken a liking to me. One time we’d gone drinking moonshine with Roy Acuff. Acuff told me you know when the moonshine is good because it bubbles up a certain way. They call it frog’s eyes. Then you know it’s good to drink.”

When he played the Earth Opera songs for Wagoner, Wagoner said that the songs weren’t for a country audience; they were for listeners of Rowan’s generation.

Rowan then went on to make a slew of records with various groups.

“I was always a seeker of different kinds of music. I wasn’t content to keep doing the same thing repeatedly. I had heard (from David Grisman) about Ry Cooder playing with Flaco Jimenez, a Tex-Mex (Tejano) accordion player. I loved that sound. I then went to Texas to meet and play with Jimenez. He was already renowned. He had me come out to a gig out in the Texas Hill Country at a place called Irene and Fidel’s. The venue had chicken wire windows; it was an outdoor/indoor dance hall.”

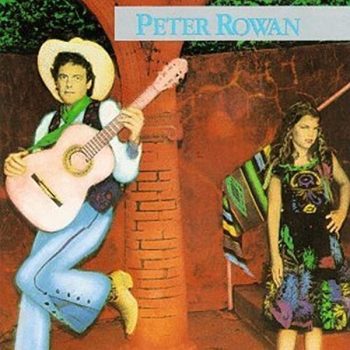

The result of these sessions was his first solo album, entitled Peter Rowan. It showcased a mix of country, Tex-Mex, rock, and bluegrass. Featuring Richard Greene (fiddle), Flaco Jimenez (accordion), Tex Logan (fiddle, violin) and Buell Neidlinger (bass), the album has iconic versions of “Free Mexican Airforce,” “Midnight-Moonlight,” “Land of the Navajo” and a breakout live performance of “Panama Red.” Half of the album was recorded in Texas and the other half at a guitar shop in Los Angeles.

Over the years, Rowan’s musical adventures have led him to explore other genres, as mentioned. A self-professed Buddhist, Rowan recorded Dharma Blues in 2014, showing just how far he can stretch. The songs on Dharma Blues are fresh, original, and new. Featuring thoughtfully written tunes like “River of Time,” “Wisdom Woman, “Raven” and “My Love Will Never Change,” Dharma Blues includes guest appearances from Jack Casady (Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna) and vocals from Gillian Welch, with instrumentation ranging from banjo and pedal steel to harmonium and water drum. In many respects, he’s a world music performer.

I asked him about his performances with Yungchen Lhamo.

“Yungchen blew everyone away. She has no barrier to the audience. When we’d go into an instrumental, she’d amble out into the audience and get everybody dancing. It was magical. Imagine a relatively tame Florida audience that came to hear bluegrass. Suddenly this beautiful Tibetan dakini comes out to them in their seats and leads them by the hand into ecstatic dancing.”

Yungchen and Rowan did several radio shows and outdoor festivals together. The song “From My Mountain to Your Mountain” features the dynamics of how their voices work together.

“She was brave. And incredibly compassionate. When we were on tour, Yungchen would go shopping for groceries and give them all away. While we were playing honky-tonks in Georgia, she’d minister to people. You must stop drinking. She’d do things like take a cab or a bus to the airport. She didn’t drive a car. But she was incredibly dedicated. This was tough on her. I don’t think chasing the dragon of music around the world is Yungchen’s thing. As for me, this is all I’ve ever known.”

“What are you working on now?”

“I’m playing with Los Texmaniacs; they are proteges of Flaco Jimenez. We are called the Free Mexican Airforce.”

The Free Mexican Airforce performs some of Rowan’s most beloved songs: “Come Back to Old Santa Fe,” “Ride the Wild Mustang,” “Midnight Moonlight” and “Free Mexican Airforce.”

In the group is Max Baca, a legend on the bajo sexto, a twelve-string guitar-like instrument, and his nephew, Josh Baca, who is fast attaining legendary status on the accordion. Together they create the core of the lively conjunto sound.

“I met Max when I was on the road with Flaco (Los Texmaniacs); he was twenty-two at the time. It’s like I’ve come full circle. We expect to go on tour in the Fall 2021.”

In addition to playing and touring with The Free Mexican Airforce, Rowan plays with other configurations such as Peter Rowan’s Big Twang Theory, Peter Rowan’s Twang an’ Groove and Peter Rowan & Crucial Reggae. He’s also making another traditional bluegrass record for Rebel Records.

I can say one thing for sure, we’ll continue to hear more and more from Peter Rowan. I don’t see any end to his musical adventures.

— —

Mike Fiorito’s fourth book Falling from Trees published in early February 2021; his other books are Call Me Guido, Freud’s Haberdashery Habits and Hallucinating Huxley. For more info, visit: fallingfromtrees.info

— — — —

Connect to Peter Rowan on

Facebook, Linktree, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Amanda Rowan

:: Stream Peter Rowan ::