Some of the best music from the past 20 years has come from artists coming off debut success, hungry for more. Contributing writer Leo Culp’s The Sophomore Series column looks at 21st century albums that prove the phrase “sophomore slump” is outdated.

Sophomore albums like Frank Ocean’s Blonde and Adele’s 21 are the truest examples of artists in their element. Each song moves along and builds on the enormous reputations of their artist’s debut. The last edition of The Sophomore Series looks at two of the most iconic projects the 21st century has to offer.

— —

If you had to name the two most iconic voices of the 2010s, it would be difficult to find two more iconic than Adele and Frank Ocean. Though they have only released five albums between them, they have been defining presences in the music industry this century. Channel Orange (2012) and Blonde (2016) redefined what R&B/ neo-soul albums could be (and I’m not even sure we should qualify them as such; they often drift outside the genre). And Adele could exist in any decade; 19 (2009), 21 (2011), and 25 (2016) are a different breed of singer/songwriter albums. They could slide into the catalogues of greats like Amy Winehouse and Aretha Franklin and no one would be the wiser.

Sophomore albums like Blonde and 21 are the truest example of artists in their element.

Each song moves along and builds on the enormous reputations of their artist’s debut. Nothing major changed, but slight additions to Adele and Frank Ocean’s formulas yielded immense returns. These albums are defining moments for the artists. Adele could live multiple lives off the royalties that came from 21, and Blonde is an album that explores solitude and inner conflict better than any other. For the last edition of the Sophomore Series, it seemed fitting to pick two truly iconic albums. Debuts very often mark important ground, but second albums are a space that set important precedent for artists as they figure out who they are and what they want to be. Adele and Ocean wanted to define this generation of popular music.

I know I have a fickle heart and a bitterness

And a wandering eye, and a heaviness in my head

But don’t you remember?

Don’t you remember?

The reason you loved me before

Baby, please remember me once more

– “Don’t You Remember,” Adele

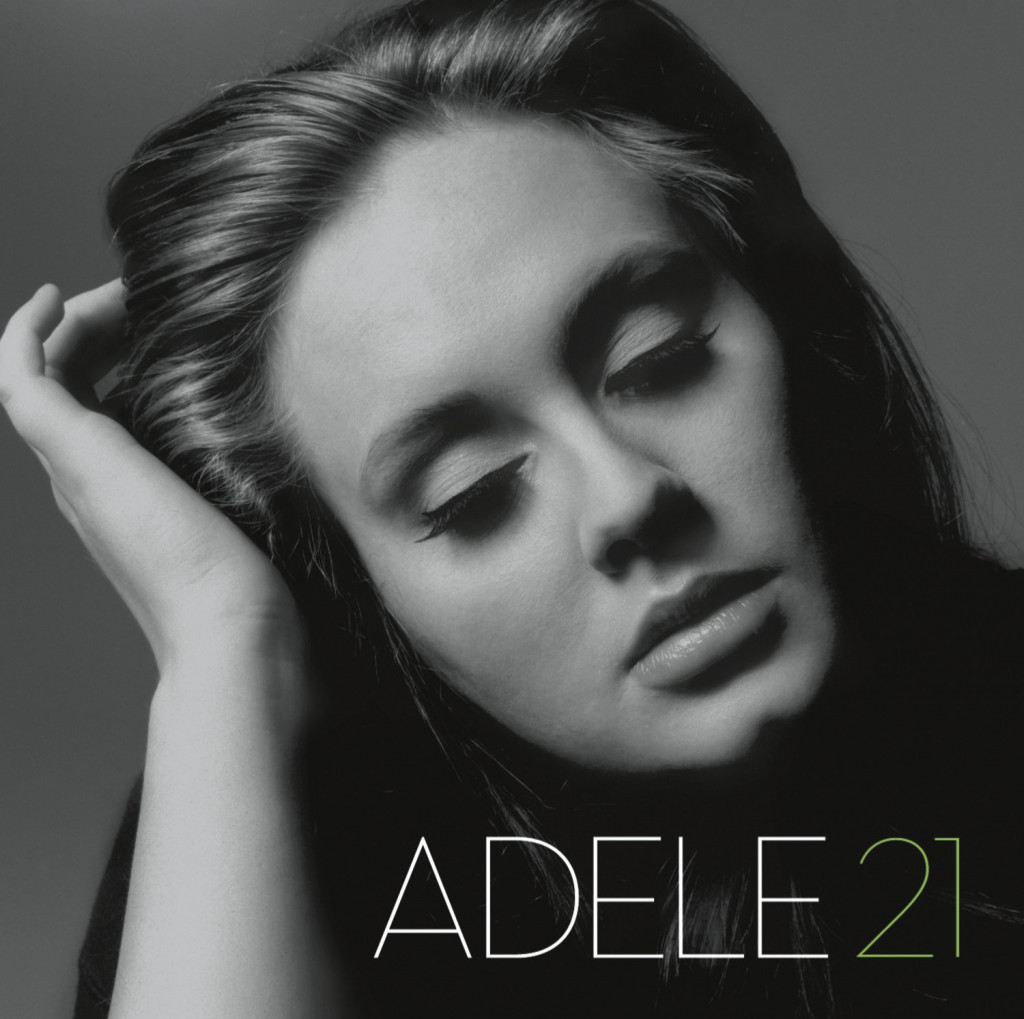

You know those movies you’ve basically seen because you’ve caught enough snippets to get the gist? That was what I thought Adele’s 21 was, but then I listened to the whole project. I constantly found myself saying, “Wait, this is also on here?” I had a similar experience with Pulp Fiction. I’d sit-in for a scene while my dad watched, but the totality of the experience when I watched it start-to-finish was overwhelming. 21 is the same way. “Rolling in the Deep” is the opening diner scene, “Rumour Has It” is the Big Kahuna Burger scene, “Set Fire to the Rain” is when Uma Thurman snorts John Travolta’s heroin, and “Someone Like You” is “the path of the righteous man” (don’t worry, I’m not going to find a parallel between this album and the gimp scene). They are greater than the sum of their parts, even if their parts could stand alone beautifully.

The point is, this album is so much more rewarding to listen to in the context of its commercial success. Without it, it’s a great album; with it, it’s a piece of history. Since her debut 19, people have been drawn to Adele’s authenticity (oh, and the fact that she has a voice like Aretha Franklin and Amy Winehouse). 21 is autobiographical, and while the lyrics of the album singe with disdain and remorse, it’s the recording of Adele’s voice and the stripped away feel of the songs that make the biggest impact. This was Adele at her most raw, her most exposed. 19 might have been full of rich songs that showcased Adele as a gifted singer, but 21 showed she was be one of the most captivating songwriters of the 21st century.

One of the defining differences between 19 and 21 is its recording style. Whether it be lyrical or instrumental, 21 is vastly different from its predecessor, and played on the vibe of people like Winehouse and Franklin. It had a distinctly folky feel, as Adele referenced in a piece by Interview Magazine. She said, “I did get really into country, which was a brand-new style of music for me, because it’s not a part of my culture in the UK. I got into blues, I got into rockabilly.”

The result of these influences is an album that feels like you’re hearing it in a small club. 21 shows firsthand the importance of production and recording styles. While multiple songs were scrapped from his recording with Adele, people like Rick Rubin were vastly important in giving it an in-person vibe. On the recording of The Cure cover “Lovesong”, Rubin said, “Today, most things are recorded as overdubs on track. This was truly an interactive moment where none of the musicians knew exactly what they were going to play and all were listening so, so, deeply and completely to figure out where they fitted in. It’s almost like a psychic connection needed to occur so the musicians didn’t step on each other’s licks, and all of the playing was keying off the emotion on Adele’s outrageous vocal performance.” If you look around on the internet, there’s a lore to this album that doesn’t follow many others. Everyone who recorded with Adele for 21 was somehow changed by the experience, and it shows.

From four to one, the most popular songs of 2011 were Katy Perry’s “E.T.”, Katy Perry’s “Firework”, LMFAO’s “Party Rock Anthem”, and Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep”. If you look around at the rest of the songs on that list, the majority are pop-bangers marked by echoes and club bass. By contrast, “Rolling in the Deep” is genuine, it connects. Truth be told, I was tired of Adele after 21 got released because it was overplayed on the radio, and didn’t make my way back to it until after it had been filtered off the radio. While it brought me back to 2011, it also seems totally disconnected from that year. Songwriters that transport like Adele are limited to the Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan category. She may not have the track record and long-term pedigree of those artists, but it’s the connection that Rubin noticed, and the connection she had with millions in 2011, that speaks for itself. 21 is an album that exists outside of time, yet seems refreshing with each listen. It’s an album every artist wishes they could make, but only a handful do. It shows what can happen when something personal meets the unfamiliar.

All my night, been ready for you all my night

Been waitin’ on you all my night

I’ll buzz you in, just let me know when you outside

All my night, you been missin’ all my night

Still got some good nights memorized

And the look back’s getting me right

– “Nights,” Frank Ocean

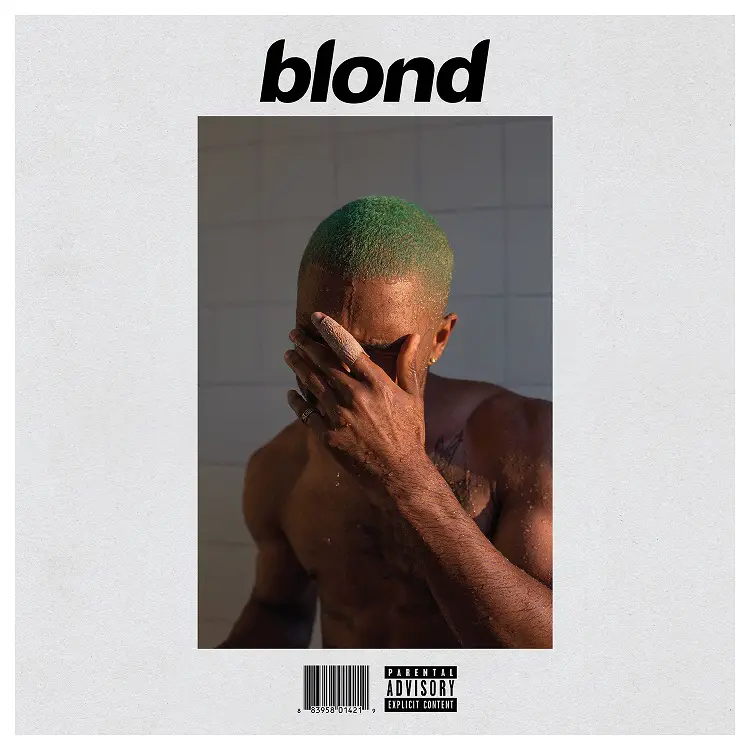

There’s a point in the middle of “Skyline To” when you realize Blonde is a perfect album. You aren’t even halfway done yet, but from what you’ve heard so far Ocean is pitching a perfect game. You have been captivated for eighteen straight minutes, each minute as inspired and beautiful as the ones before and after them. Ocean is the logical successor of Prince. In the same way Prince built mystique through odd stories, prolific releases, and label disputes (oh, and ridiculously good music), Ocean has stayed as in-the-shadows as any celebrity this century. With interviews rare, and new music even rarer, it seems a running joke in music that Ocean may never drop that ever-sought-after third album. And still, week after week, message boards are filled with people trying to find the clue that will lead to his next album’s release date. Few artists captivate like Ocean, Blonde shows why.

Like 19 and 21, Blonde seemed like a continuation of Channel Orange, its focus was just shifted. While the album was recorded in similar fashion to the debut, the rough edges and mixtape vibe of Channel Orange got smoothed over. Blonde, as I mentioned above, is a masterpiece, just as Channel Orange is, but it has an indistinct musical narrative that very few artists have been able to achieve. Ocean’s process is one that could only be achieved in the 21st century. Producers and musicians and engineers the like work relatively independent of Ocean, as he crowdsources ideas to fit into his master plan. As producer Buddy Ross said about Blonde, “No, I don’t think he wanted to let people have full context. He’s like a collage artist in a way. We were all these bits and pieces that he’d send off to do our thing on. But we’d never see him putting it together.” This was similar to his process on Channel Orange. In an interview with Complex, producer Malay said, “He’s the true storyteller. I don’t think anyone during any given point during the creative process knew what was happening.” Ocean has long been known for his reclusive nature. This headfirst dive into mystery is, if anything, the natural progression of his artistry. Channel Orange was a revelation, and was made by Ocean through the help of others. Blonde, on the other hand, is merely complemented by the help of others.

There’s an amazing amount of maturity that typifies Blonde. In an interview with the New York Times, Ocean talked about the impact of voice effects on the project: “Sometimes I felt like you weren’t hearing enough versions of me within a song, ’cause there was a lot of hyperactive thinking. Even though the pace of the album’s not frenetic, the pace of ideas being thrown out is.” Nikes goes from Ocean reflecting on his own mortality seen through his resemblance to Trayvon Martin to delving into narrating a dwindling and toxic relationship to reflecting on how despite his younger age he’s taking care of his partner. Each idea is looked after with care (so much that UC Berkley even hosted a class on it the album), and those vocal effects serve as the medium for his conflicted thoughts. It’s easy to get lost in the album, but everything comes back to Ocean. There are times you forget there’s a man behind the music, but you’re quickly brought back to reality.

My personal favorite moment on Blonde is when Frank Ocean sings on “White Ferrari”, “I care for you still and I / will forever / That was my part of the deal, honest / We got so familiar / Spending each day of the year, White Ferrari / Good times”. This “Here, There, and Everywhere” Beatles referenced sealed my love of Ocean. Spending a chunk of his recording time at Abbey Road in London, he was inspired by the Beatles, Stevie Wonder, and the Beach Boys. The sprawling Blonde focuses on Ocean in all his forms, carrying on the legacy of perfection the above artists mastered. When artists open themselves up, beautiful things happen, and what made Blonde different from Channel Orange was Ocean’s willingness to make this project more personal. As Buddy Ross said, he’s a “collage artist”; this album that is connected by its fragmented nature. You never know what is around the corner, but it’s often music as you’ve rarely heard it before.

Pieces of History

Nothing monumentally changed on these artists’ sophomore albums. Instead, Ocean and Adele look further within themselves, shifting their focus to match what they found. Adele dove into what happens when you strip everything away. She almost erupts out of 21, breaking the already fantastic mold of 19. Ocean found himself grounded in the conflicts that defined him, making an album that flows between these thoughts. Channel Orange was an amazing album, Blonde is an experience. Both artists had successful formulas, they just widened their comfort zone on their second time out.

An artist’s second album says a lot about how they view themselves. Throughout the course of this column, it’s clear the most notable trend set on these albums is the idea of change. This does not mean change for the sake of it. Rather, an artist developing the understanding of their brand yields the greatest return on investment. 21 and Blonde exemplify this perfectly. You would be hard pressed to find a better voice than Adele’s, so molding the music to the sentiments expressed by her voice made 21 so special. And Blonde could only improve Channel Orange if we delved deeper in what makes Ocean tick. There’s no tried-and-true method to nailing these projects, but artists that understand their own path to growth are most primed to make a long-lasting career. Blonde is the last Ocean project we’ve gotten, and Adele has only released 25 since 21, but it’s clear these artists will be in our lives for a long time. After these projects, who’s going to complain?

— —

Leo Culp is currently a junior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill studying Media/Journalism. He hosts a local radio show in Chapel Hill, and loves watching Liverpool soccer and Carolina basketball. He is always trying to find something new to learn about music, and is a proud Atlantan.

— — — —