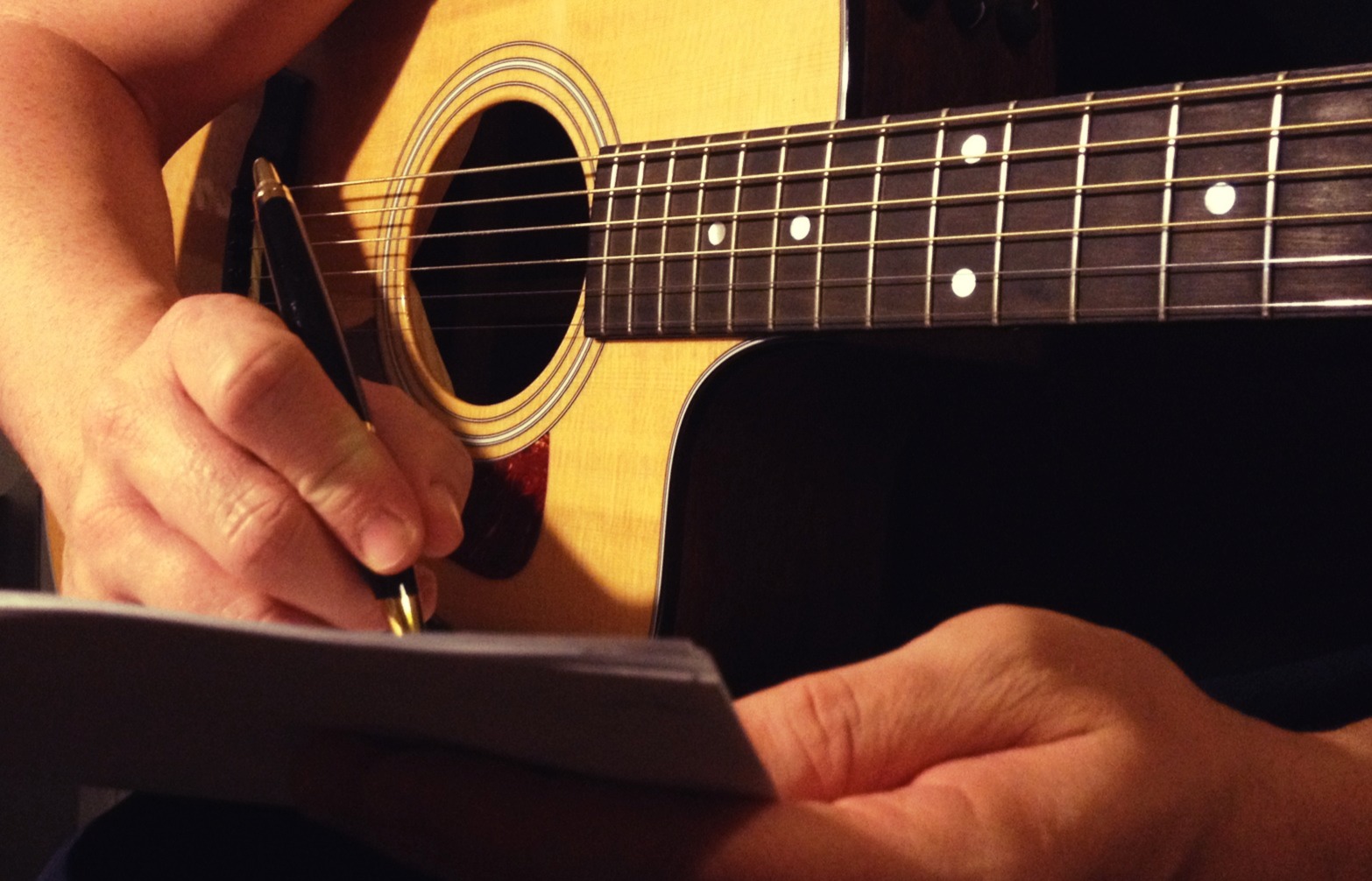

When I was twelve years old I decided to learn to play guitar. I chose guitar class as my musical elective and absolutely hated it, and for about a year the guitar was something nothing more to me than a homework assignment. Then, as soon as I left the guitar program at my school, I began to truly love playing for the first time. I printed every free music sheet I could find of my favorite songs (mostly Metallica at the time, somehow) and spent every spare moment after I got home from school practicing and drilling and bleeding on that guitar.

Eventually guitar playing became a conduit for songwriting, the outlet that would become my true musical passion. I wanted to become like the great songwriters whom I idolized, the brilliant artists who transformed the potential of music and lyrics to become a transcendent force in peoples’ lives. I signed with Warner Brothers Records when I was 20 years old and released my debut album Great Falls in March of 2015.

By that point, having found that my interests were straying beyond music, I had already begun nurturing a desire to write prose — I started working on a novel (which I’m sure will be read by seven people, including my parents) and penning columns.

Throughout this process of discovery when it came to studying the crafts that interested me and trying to better myself, I obsessed over the greats in whatever field I pursued. I scoured the internet for quotes and anecdotes that would let me into their process, and I obsessed over the work habits of my peers, particularly when they didn’t seem to match my own. My songwriter friend routinely works until 4am, but I lose the ability to focus well by about midnight. What’s wrong with me? I need to train myself to stay up later so that I can achieve greatness. And this legendary guitar player used this method to become great, so I should use precisely that method to develop my own playing. I found myself in this mindset time and time again, and each time I became frustrated by my inability to successfully apply the habits of those I studied to my own development.

Over the course of this cycle of obsession followed by frustration, I learned the most important professional truth I’ve ever stumbled into — that the habits and methods that others employ to achieve greatness are relevant to me only as inspiration. I was looking at each person who did what I wanted to do, who became what I wanted to become, as a direct road map to success. If someone was a great guitar player, and I wanted to become a great guitar player, or songwriter, or writer of prose, I had to emulate their process exactly.

But one instrument in the hands of two different people is actually two instruments. Why? Because the real instrument is each of us. And we are all of us tuned a bit differently, built from unique materials, played with a distinct technique. What works for someone great might in fact be the exact opposite of what you need to thrive.

Want proof? Whatever your area of focus, find quotes by the five individuals you consider to be the greatest to ever work in your craft. Read the strongly-worded statements each one makes about how to excel. Chances are there will be at least one piece of directly conflicting advice. These quotes and directions are well-meaning, and they may work well for someone, somewhere. But it may not be you, and it’s important for us all to recognize that that’s okay. I know very little about how Stevie Wonder composed Songs in the Key of Life, an album I consider to be one of the greatest in history. But I learned what I could from it by studying the product itself, and that is what I suggest as the most effective way to learn from our idols.

Search more for the why in the greatness of their creations, and perhaps focus a bit less on the how. If you are most creative when you work for two short hours right at the start of the day, then ignore the laughter of your peers who begin at 3pm and go on into the middle of the night. It might lead to success for them, but that does not mean it will for you. Don’t be discouraged if your habits and approaches and personal keys to progress aren’t recognizable to each of your peers, or relatable to those of your idols. Your path is your own and your instrument is perfectly tuned. You just may not be in the same key as everyone else.

If I had to boil down my advice to something a bit more concise, I suppose it would be this: Ignore this article and articles like it.