As Nick Murphy once again immerses himself in being Chet Faker, the most important piece of the puzzle remains the authenticity of it all.

Stream: “Low” – Chet Faker

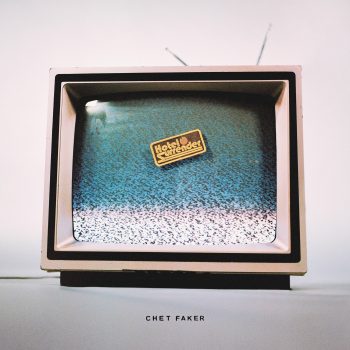

“Music does something; I just don’t know what it does. I just accept it as the sky is blue.” These words introduce – and thus, reintroduce – Chet Faker, (Nick Murphy) on the opening track of his latest album, Hotel Surrender (released 21 July via Detail Records). The lyrics, from the song “Oh Me, Oh My,” feel befitting as an overture for Hotel Surrender, but also categorically summate Murphy’s own feelings about music as a whole. The music is the meaning, and everything else simply follows suit.

The death of Chet Faker was relatively quiet, and ostensibly swift. Nick Murphy wanted to just be Nick Murphy. And then, he couldn’t: the music was leading him back to that old haunt – the ghost of Chet Faker could not be ignored. And thus, Chet Faker was reborn, and subsequently, his latest output, Hotel Surrender was born.

“I think as long as it feels natural, it’s the way it’s meant to be, because there’s a lot of confusing things out there,” Murphy explains to Atwood. “…I feel confident that as long as the music is always what leads me to these places, then it’ll always make sense to me.”

Hotel Surrender deftly navigates raw emotion and natural feeling, expounding on self-actualization and the necessity for being honest with oneself.

Songs like the aforementioned opening track, or the sensitively sentient “So Long, So Lonely,” or the empowering single “Get High,” all exemplify Chet Faker’s knack for curating narratives that are simultaneously self-aware and personal, and pervasive all at once.

And just because I tried, doesn’t mean I’m wrong

Just because I cry, doesn’t mean I’m not strong

Just because we lie, doesn’t make it wrong

– “Get High,” Chet Faker

As Nick Murphy once again immerses himself in being Chet Faker, the most important piece of the puzzle remains the authenticity of it all. Hotel Surrender exudes this wholeheartedly – surrendering, as it will, to redolence and the need for genuine feeling. It is an album teeming with copacetic catharsis, allowing for Chet Faker to exist freely and fully in creative expression.

“If I would have a message, it’s that the expression, no matter what, is sort of the tool for us for life, to help us through life,” Chet Faker says.

Read Atwood Magazine‘s full conversation with Chet Faker below.

Stream: ‘Hotel Surrender’ – Chet Faker

:: A CONVERSATION WITH CHET FAKER ::

Atwood Magazine: Obviously, you weren't Chet Faker, up until about maybe about a year ago. You were, and then you weren't? How does it feel sort of re-entering into that mindset, as Chet Faker, going from doing Nick Murphy and being yourself, back to this persona?

Chet Faker / Nick Murphy: Well, first of all, the way I see them, they’re not mutually exclusive. They’re different projects, which was always the intention, a little bit, I think just as a sort of self-freedom. Originally, I had to sort of pretend to kill it [Chet Faker], as a sort of point. Not to myself, but to everyone else, like: “I’m doing what I’m doing. Please don’t tell me what to do.” You know, I’m such a staunch — like, ever since I was a child, I didn’t like the seatbelts. I would scream the whole car ride. I need my freedom. But, yeah, it feels good.

I mean, everything I’ve done, literally, everything I’ve done, as a musician has always been led by the music. So it wasn’t like, “I’m gonna do a Chet Faker album,” you know? Or I want to do it, or anything like that. It was last year, I got this studio just around the corner at the beginning of 2020. My manager found it for me, it’s a tiny little space. But I hadn’t had a studio before, that wasn’t in my house, since Built on Glass. So it’s been years; you know, I other booked studios and stuff like that. Once I got this space, I didn’t realize that I missed it — but, once I had this place to go at any time, every day, I was going down there. I was just writing all these songs. And it’s just me, you know, I wasn’t working with an engineer or anything like that. And I remember around like, early summer and spring last year — I keep [the songs] all in playlists on my computer, and just sort of looked at them and [realized], “Oh, this is an album.” Like, none of this is filler. These are all totally, very clear songs that have a point to them. And then also just being like, “And this is a Chet Faker album.” It sounds like Chet Faker, to me. It feels like the way — it’s the same process as I wrote Thinking in Textures and Built on Glass, which was just me, you know, engineering, producing, and doing all that stuff. Versus like, with most of the Nick Murphy stuff, I almost always work with someone else.

So, yeah, I literally felt like I just woke up one day, and I was like, “Oh, I have a Chet Faker album.” And I sent it to Alex, my manager, and he obviously thought the same thing, but he doesn’t like to say that shit until I say it, which is good. You know, because I get really easily confused. But he was like, “Let’s just give it the weekend and chat.” And then on Monday, we both said it at the same time. So it wasn’t even like a choice. It was like, “Okay, this is where I’m at now,” And in a way, it was kind of like I didn’t really have a choice in it. I mean, sure I had the choice to not put it out, but that has definitely never really been my M.O. of creativity. It’s like, you share everything, you know? I’m like a chronic over-sharer; but that’s my whole message. If I would have a message, it’s that the expression, no matter what, is sort of the tool for us for life, to help us through life. So, yeah, it’s cool. I mean, a lot of what I needed to do, and what I will probably continue to do with the Nick Murphy project, was allowing me to kind of create some more freedom with the Chet Faker project. There was sort of like, too many conflicting needs in just one project. So I needed to kind of go over here to do this, so I could do that. So it really feels really fun, and light and fresh, you know? It’s good.

Do you think that you'll continue to oscillate between the two? You're just gonna just continue doing both?

Chet Faker: 100%. I mean, technically, I already have.

True!

Chet Faker: I put “Low” out in October, and since then I put out another cassette on the Nick Murphy thing. So yeah, nothing big, and I haven’t been super clear about it, but yeah, they’re separate projects. And they’re very much like yin and yang for me.

Streams : “Low” – Chet Faker

Do you think they intersect at all? Or have any overlap?

Chet Faker: I mean, they have to, because it’s me. So like, for sure. But I haven’t yet written a song where I’m like, it can go either way. I think the only place it would be both is in the earliest stages, you know? Because eventually, a decision is made that’s best for the song, and it just goes in one of the directions. The [Nick Murphy] stuff is very selfish music, it asks for a lot from the listeners. It requires a lot, and it sort of assumes that the listener has time and is putting effort into this journey. Versus the Chet Faker stuff, I’ve never been about that. It’s like, it’s always been very giving, and it’s like, “Yo, vibe, please enjoy it.” They’re just like different types of music, you know? And I like both types. Most people, the majority just prefer the one that just gives, because a lot of people are busy or, just like, they live their lives. They’re busy trying to live their life, you know, not everyone has the time to like, get into music. Some people are trying to pay the bills or whatever, and they just need a vibe, they just need a good vibe. So I think that’s where that kind of splintered off a bit where it was like, “Well, I want to go into this, like, deep, creative, spiritual journey.” But I also don’t want to — I’ve built this thing that has this sort of connection to other people, and it’s not really about me. It is, but it isn’t; it is bigger than me, so to speak. I think that’s kind of like, well, I need this, but I don’t want to ruin this either.

I feel confident that as long as the music is always what leads me to these places, then it’ll always make sense to me.

As long as it’s fun, and not too confusing for you!

Chet Faker: Well, even if it’s confusing, I think as long as it feels natural, it’s the way it’s meant to be, because there’s a lot of confusing things out there. Often things that are new or challenging, are confusing and feel wrong. But as time goes on, people are just like, “Oh, this made sense.” I feel confident that as long as the music is always what leads me to these places, then it’ll always make sense to me. And I have no regrets, you know?

So with this album, from listening to it, there's a lot of relatability to it. And I think it really strikes a chord. Were you trying to put any sort of like intention into that? Or was it just like natural flow that was coming?

Chet Faker: It was totally, definitely natural. Like I said, I really wasn’t trying to write a body of work at all. There was no — it was so unintentional. But that doesn’t mean it’s without a message. It’s the first full length album that I’ve written that just sort of unfolded, it just kind of came out. And I think it was because I was really going to the studio, and I wasn’t going there with the goal to capture hits or anything like that. I was going for the process of creativity, of making music as a kind of technique, or tool for just feeling a bit better in myself and in my life. And I started to discover that, or rediscover, I suppose, that there are types of music and ways of creating music and playing it, that can really help you tap into the present moment in front of you, and you can find a kind of joy in that. And that became a sort of North Star for this record. I was just sort of like, following where it went. And that’s where the title, Hotel Surrender, came from, you know, because there was just this theme of surrender to this kind of natural performance of things. And a lot of the songs — “Get High” was like, just me playing the piano, and that’s how I’ve always kind of played the piano, but I never really recorded it because I was like, Oh, it’s that’s super natural so therefore, it’s like, not good. You know what I mean? Often people deny the things they do.

Stream: “Get High” – Chet Faker

Yeah, you convince yourself that it's wrong.

Chet Faker: Well, we always associate hard work with quality of work, which most of the time is true, but it’s not always. So, yeah, I just started to play and was following that. And it was just really helping me tap into this joy, you know? I think it was really kind of, like, joyful. And when the pandemic hit, about three months into writing this stuff, it sort of stripped away everything. And then I just kept doing the same thing. I would just go to the studio every day, and it sort of focused that concept even more, and I felt like I really rediscovered just the joy in music. I mean, it sounds so simple, but it was just — it feels good to play music, and to listen to it, and it feels good to listen to music that was played that felt good to play. I was like, oh, this doesn’t always have to be some, you know, metaphysical meaning, some challenging thing. This is kind of a tool to ground us in what’s in front of us, and in our lives. And it doesn’t mean it makes life all good. We can still be in a bad place. And some bad things happened to everyone last year, including myself, but I felt like I discovered that this works. You know, this is tiny, it doesn’t fix everything, but it can temporarily put you in a really great place. And I gave that name, Hotel Surrender, that was the name I gave for that space. You know, “checking in,” that’s where the hotel bit came from, and sort of surrendering to whatever’s going on in front of you; like, “Oh, I don’t feel good.” But you check in, and you surrender to it; and then, on the other side of that, was this kind of joy of being, you know, that you’re fundamentally okay. So that was what drove and wrote all the songs. And then when I had it, I was like, I’ve got to give this to people. I’ve got to share this, because there’s probably — if it helped me, it’s surely going to help someone else. So that was the message behind it, even though it wasn’t necessarily like, “I’ve got this message, let me write songs about it.” It was more that the message itself wrote the songs.

That's great. I think specifically what comes to my mind is the lyrics of “Low,” they sort of touch on exactly what you're referring to. Do you have a favorite lyric on the record that you can pinpoint that you're proud of? Or one that particularly strikes a chord with you?

Chet Faker: I am actually so bad at remembering my lyrics a lot of the time [laughs]. Yeah, I’m not sure. I mean, “Oh Me, Oh My,” like some of the lyrics in that. It’s usually the first line of a song that is what I’m most excited by, you know? I mean, “Low” is pretty good. Like, “Look, whatever I’m good, it doesn’t mean that I’m perfect.” I like that line. That’s good; that’s very, very human. When you try to vibe with yourself, but it’s also like, look, I know I’m not perfect, but, you can still let me vibe out with myself a little bit.

Stream: “Oh Me, Oh My” – Chet Faker

Yeah! Do you have anything that particularly puts you into that creative mindset? Or is it just always an undercurrent, just when you're making music, whether it's Chet Faker, or Nick Murphy projects? Do you have something that sort of brings you into the creativity?

Chet Faker: Not really. I think it’s more of, I always think of creativity like a faculty, it’s an ability that everyone has. But unlike moving your hands or doing something, it’s like a space in your mind, and it requires a kind of mindfulness to recognize it, because it’s very, very fleeting. It’s almost like a whisper. So, to me, I think you can practice your creativity, but the trick with creativity is just expressing and creating just because. Once you start bringing reasons to it — everyone’s creativity is a child. It’s reverse psychology, and anyone who has a creative output will agree to this, that when you try to force it, it stops giving you the good stuff. And when you stop trying to force, it gives you the good stuff. So it’s literally a child, it’s your inner child. And like a child, you can’t bring this adult attitude to it; but that’s difficult, because also as an adult, you want to have a regular output. So yeah, it’s this compassion that you have to bring to yourself as a creative. And you’re constantly walking this razor-thin line between pressure and compassion for yourself, you know? But for me, I don’t know if I have something that gets me straight into that space, but there are things that I do regularly that kind of regulate my access to that space. I like drawing, and like, these are kind of pointless, completely pointless. But the pointlessness is really important in creativity, because you’re telling the child — you’re not putting pressure on the child, but you’re still making it work. So that’s my approach: you’ve got to be around it. And you have to always have that extension available and happening. So, you know, going to the studio is key; but sometimes it’s not going to studio for a while, and deliberately holding off. It seems to be about this ebb and flow of energy where it’s like, the energy needs to always feel special about its action. And it’s really a child, you just think of it like a child. But then also, the hard part is that there are some parts in a creative process that is the opposite: it’s technical, you’ve got to focus.

Do you find it easier to do production or lyric writing? What seems to come more easily?

Chet Faker: Probably lyrics; I only say that not because I think that all of this is easy when I’m doing it, but because I love production, doing production, but I think I love it because it’s difficult, you know? And that’s like what we were talking about before where it’s like, it’s not easy. So therefore, you feel the reward. You feel like it’s you, you know? Versus just singing and playing piano — I enjoy doing it sometimes, but I don’t just love doing it all the time — it’s just too natural, a bit. And that’s really what this record was about, it was me connecting with actually finding the joy in that naturalness, as opposed to what I was just talking about, which is having a kind of intellectual — bringing your mind to it rather than your heart and your body. But, I mean, I write poetry a lot as well, lyrics, and I have all this stuff on my notes on my phone as well, and I’ll never look at it. But, I don’t know if one is easier. You know, I would be hesitant to sort of use that language because the child’s listening, and then you put ideas in the child’s head. It’s like, “Ah that’s easy, then I shouldn’t try. Oh, that’s hard, then…” You know?

As a performer, you seem to put a lot of value into the way you structure everything in a live show, and it translates really well, from listening to the record on streaming, and then seeing it live. Is that something that you are conscious of? Do you always try to think about live performance as well?

Chet Faker: Absolutely; all the time. And it stresses me the fuck out, to be honest; because it’s not the 70s. It’s not four dudes, a drum kit, bass, two guitars and three mics. That’s easy to replicate. But I mean, especially with the Chet Faker shit, I’m like, reverse down-pitching, stutter-effecting 20 different plug-in effects on like, one part. How the fuck am I gonna do that live? It’s literally impossible. And you have a choice: either, you don’t do it like the sound it sounds like and people go, “It sounds shit,” or, you do do it, and they complain that it’s all playback. Like, yo, no fucking shit it’s all playback; it’s digitally manipulated. It’s literally impossible to do live. But people are never happy.

But I mean, that was a long time ago. So I’m not sure how or if I approach it the same way, because I really — even the past five years with the Nick Murphy touring, and like I even doubled down even more on the live stuff and it was really, I mean, I think the last five years I’ve put in some of the best live performances of my life. But most of it was — we were just at a crossroads as a species in terms of music, where you can balance them, and it takes a lot of work, and it’s good to try and balance them, but it’s not natural to the music, you know. But I definitely have to put all my energy on the stage, because I get very uncomfortable. I don’t particularly like being in front of people; that’s not my calling, performing. Expression is my calling, you know, and I have these feelings and I like expressing them; but doing it in front of like, 30,000 people — don’t get me wrong, it’s amazing, and I wouldn’t like to get rid of it. But I’m usually like, kind of stressed out and anxious when I’m up there.

And obviously, the last year the music industry has shifted so dramatically. Now that things are going back to quote unquote, “normal,” what do you think that's going to look like?

Chet Faker: Well, I’m already seeing it in [New York]. People are just being crazy. They are making up for lost time, and then some. And I think that’s what it’s going to be like, I think it’s going to be really messy. And I think it’s going to be hell on earth for introverts for the next 5 to 10 years. But I think as a species, we’re probably going to be after having a good time, and I think it might be a little bit manic, but I think there’s going to be some fond memories for everyone.

Is there anything that you think came about during COVID, with music, that will stick around? Like, things that had to be adjusted. Do you think that it's all gonna go away in time? Or do you think that people are going to stick with some of these new things?

Chet Faker: I mean, I think it obviously depends on person to person. It does feel like it feels to me, like 50% of people refuse to learn a lesson; because it was too uncomfortable for them and are obsessively trying to go back to normal. Right? And it feels like the other 50% are like, “Yo, we have to change the way we think, the way we’re doing things; the planet is speaking to us.” And it’s saying stop, you know? It’s like, the fucking universe is telling us, “You guys need to chill.” We’re actually killing the planet, you know? It’s not we’re not even just killing grass or trees or a species, it’s the whole fucking thing itself. And we look out with these crazy telescopes, and there’s like, nothing. I think there’s like, one Class M planet, that’s like 15,000 years away, right? I don’t know if there is one closer than that. Shit’s crazy, man. But I don’t know what might have changed. I do think for some people, there’s maybe a bit more love and empathy towards each other. For me, the big thing was just how short life is, and how fleeting, and also how much of a sort of constructed framework society is.

I think my biggest takeaway was just Mother Nature. And just that, like, she’s just the answer. And yeah, and I think the biggest shock I have walking around, especially in New York, I’m just like, “Why are there no trees? Why aren’t we planting trees?”

But, I think creatively — whether or not the pandemic affected it, I think it might have galvanized it — I do think we are in a new stage of what being a “creative,” and a musician means. I think the output is much higher. And you cannot simply just be a musician anymore either; you have to have a visual output. And I think creatives have become multi-disciplinary, it’s almost expected. I think that’s exciting; it’s more work, but it’s cool.

Do you think the increase in output is going to dilute the quality, or just the industry in general?

Chet Faker: I mean, I think it’s been happening for a while anyway. I mean, you don’t need labels, but that’s good. But I think the problem is, it’s good, and it’s bad. It’s good, because I think the concept of even really getting paid for music is ridiculous, on a big scale. But on a mid-to-smaller scale, it’s like, well, we should pay musicians, you know, because there are a lot of artists, historically, that didn’t tour; and to be a touring artist is not the same as a recording artist. They’re completely different. I actually think we’ve almost forgotten that one of the most common types of creatives, at least from the past, historically, are very introverted, sensitive individuals. But it’s almost like, now we think a creative is the biggest extrovert, you know, and that’s what it’s meant to be. And you see things, people saying shit about artists, like, “Oh, they signed up for this,” as if they wanted to be the center of attention; there are a lot of artists that never played a show their whole career, but gave us beautiful music, and those artists couldn’t get paid anymore in the world we live in; they can’t make money from it. They can still make music, and luckily, the technology’s better, but we’ve essentially limited the types of artists that can create because of this.

You really can't be an artist and not tour anymore, unfortunately. It's truly impossible, if you want to have a career.

Chet Faker: No, it is. Or even do it as a job, which, it’s fine if you don’t want to do it as a job, but that means it’s less time dedicated to the calling of music, you know? For me, if it was the 80s, I would tour a lot less. I would probably do 10 shows a year, maybe 20 max — probably less, actually.

But now you're obligated to book a tour.

Chet Faker: I’ve got to make the money to pay for the time so that I can explore making more music, But I think as a whole, like, I think it’s good. It will be good for us in the long run. I think right now, we just happen to be in this period of experimentation. You want to know what’s interesting? Audio quality, with streaming coming in, it’s the worst it’s ever been. They’ve done studies on the emotional response of people towards the resolution of audio files, and people who listen to lower res, there are certain emotions that are more highly stumped, like you react more to certain emotions in songs based on resolution. Basically, they found that the low resolution audio people were more likely to feel feelings of aggression, excitement, energy, anger, things like this, right? And then with high resolution, we’re more likely to feel things like sadness, happiness, you know, these kinds of things that you might argue maybe are a bit better for our spirit; less basic, less carnal, less violent, in a sense of the spirit, and more harmonious. Which makes sense, because the more information you remove from an image, harmony is built on interrelations of information; but rhythm is not, it’s just loud, soft, loud, soft, loud, soft, right? So it kind of makes sense; but if you look at that, and then look at the two biggest genres for the past 10 years, it’s hip hop and EDM, which are both built on energy. And, and it makes me wonder, like, how much that plays in terms of people getting that reaction. You know what I’m saying? I mean, the 90s was the last time we really saw ballads as a regular part of pop radio. They pop in every now and then, but in the 90s, it was like every second song was a ballad. And that was before we were listening to low bitrate mp3, we were still on CDs, which aren’t great, but they’re better than what we listen to now. Now, Spotify is doing it, and I know Amazon’s about to do it, these higher res — they’re about to start streaming music at a higher fidelity, again, we’re moving back up to it. I am really, really interested to see what that does, to people’s listening experiences. And what if, all of a sudden, everyone’s listening to pop ballads again, or something, you know, what different kinds of music?

But also, most people, when you play, can’t tell the difference. Sure, you can’t tell the difference, but you feel the difference. There are lots of things in our life where you can’t tell the difference, but you feel it — like with human relationships, you might not be able to tell someone’s lying at the time, but over time you feel that someone’s lying. That’s why people love vinyl, because it’s a really full spectrum.

I’m saying it’s better to fail doing it your way than to fail doing it someone else’s way.

That’s fascinating. But, you know, as someone who has experimented with different pools of music, and over the last 10 or so years done a plethora of different things, what advice would you give to someone who doesn't quite know where to begin? Or how to choose what lane they want to be in?

Chet Faker: Well, my advice would be to do everything, until one becomes very clearly the center of where you are, where you’re meant to be going. I don’t think choosing one, and focusing on one because we’re told that we’re supposed to focus on one is the answer. When it comes to creativity, I think you’re supposed to do it all, and it just becomes clear, or you find you’re drawn to one more and more. But I think with creativity, it’s just intuition; and, unfortunately, it’s not really something it’s designed for capitalism, so compromise is definitely a part of it. But like, I was doing everything, you know, and then when some songs got a bit of traction, then I doubled down and focused on that lane, but only when that happened. And now, I still try, and I draw and I do everything else because I think they all spring from the same well, and only you really know. I’m saying it’s better to fail doing it your way than to fail doing it someone else’s way. So you should follow your instinct; that’s kind of my point. I know that’s not a very fun answer.

I think really, at the end of the day, what I’ve found people appreciate and are excited about, is when someone fully commits to themselves and openly takes a risk creatively in a public forum. People almost always appreciate it. They will criticize you for it, that’s the trade off, but give them a little time, they appreciate it. And they don’t always tell you to appreciate it; so it’s actually kind of selfless in a way. But that’s always been the case throughout — I mean, when Kid A came out, everyone trashed it, you know, now it’s Radiohead’s best album.

I mean, it's always going to be uncomfortable, and people are going to feel some type of way about it.

Chet Faker: The trade off of being a creative is that you don’t get to know what you’re doing until after you’ve done it. That’s what being creative is; and I think that’s what I mean. It’s like, whenever I’m confused about who I am or what I’m trying to do creatively, I just know if I’m thinking about it and getting stressed, I need to go and do some work, any kind of work. I have to do a lot of it, and then it begins to make sense. Just get it out, you know?

— — — —

Connect to Chet Faker on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Jelani Roberts

:: Stream Chet Faker ::