The KPI obsessed model of music streaming cheats artists and listeners. Is there an emergency exit to this stupid, tawdry ride?

I hate music streaming.

That might seem odd – I’ve written about music for years, surely the unprecedented access to artists should fill me with joy, not dread. Let me explain.

It is 2010 and I am downloading Franz Ferdinand’s debut album from Mediafire. I searched “franz ferdinand franz ferdinand rar mediafire” on Google (before a billion LLM articles descended on it like carrion crows) and then I clicked download. I was a hopeless pop culture contrarian for six years before that, refusing to listen to anything aged less than 40 years – a middle schooler that pretended to listen to Bach but at the 7th grade dance felt something sexy and decidedly contrary to his Catholic upbringing gurgle in his stomach while “Take Me Out” was bumping. I had finally given into the gurgle.

My ritual that summer was to go to Wikipedia, find a genre, grab a few representative albums off of Mediafire, sit, and listen. Until around 2020 I managed to keep up the basic shape of the ritual. If you named a year and a season between 2010 and 2020 I would be able to tell you, down to the track number, what music defined that epoch of my life. I could scroll through my music collection, sorted by download date, and see the gradient of my life reflected back at me.

But around 2020 streaming became too big for me to be stubborn. It swelled and smothered other listening options, and the convenience to cost ratio of maintaining my own collection of music on my hard drive flipped in streaming’s favor.

A few people accused me of being obstinate and one person gave me an earful about “Apple is the future!” but the ritual, for me, made me focus on listening. I had started writing about music as a journalist and reviewer in 2017, so it made sense for me to want to take some ownership of the process. Standardizing artist info? Yes please. Tediously correcting track names because xXanaxRavenXx botched them making the .RAR? Chef’s kiss. It was all part of rooting myself in the music, like cooking a meal or taking longhand notes.

The switch to streaming was a genuine disruption for me and, I argue, the shape of music listening in general. Why? Well, in 2022 my interest in music almost entirely collapsed.

* * *

Streaming platforms dominate music listening, but I don’t think they’re particularly well designed for the task.

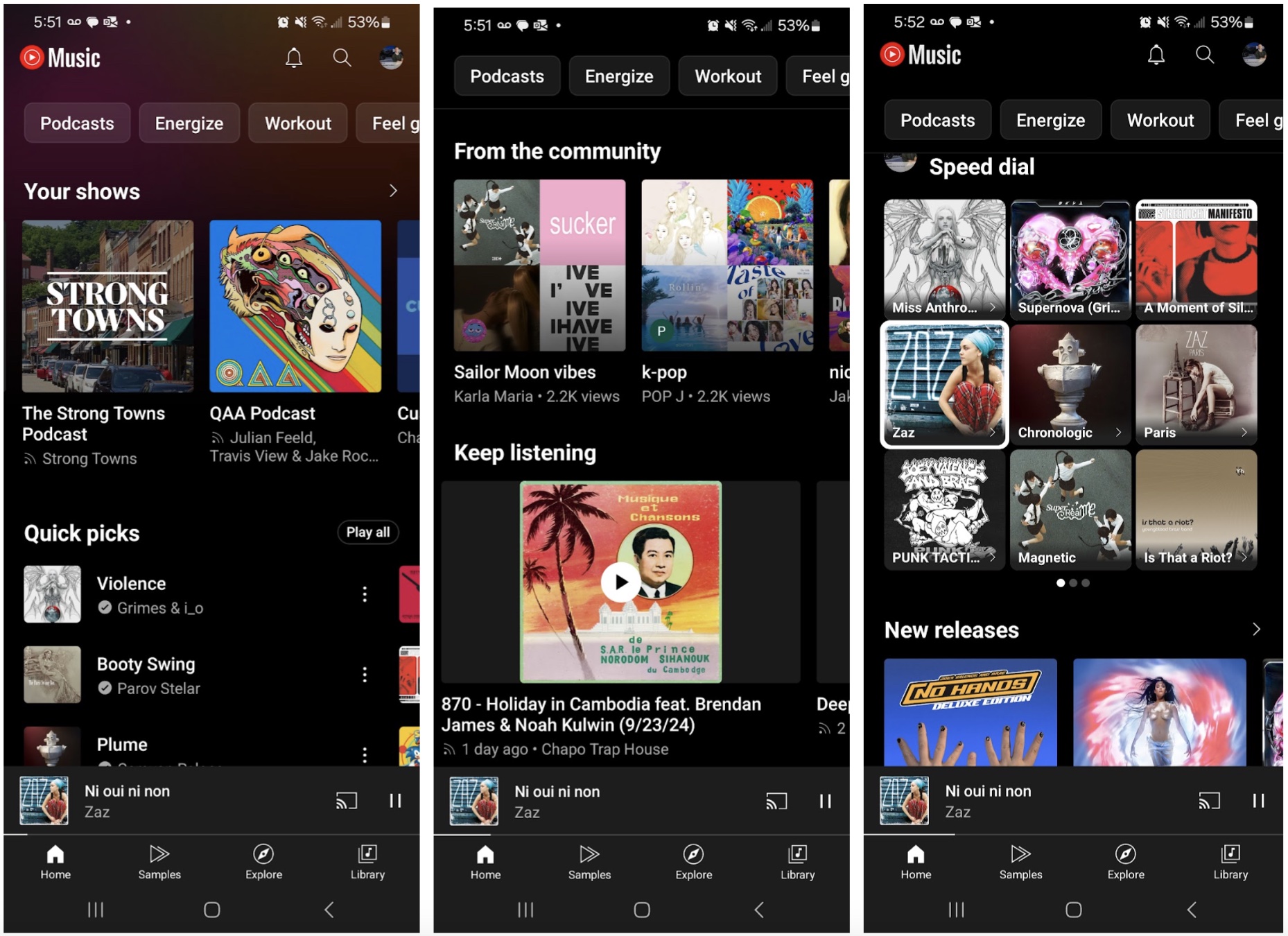

Let’s talk first about user experience. Despite how obtuse my formative listening routine was, it was fairly streamlined – nothing took me out of the process. Download, extract (close WinRAR popup), listen. Streaming, for its alleged convenience, complicates this. I use YouTube Music. Every time I open the app, I am immediately bombarded with a user interface that looks like this.

Podcasts! Energize! Workout! From the community! Even the categories that I find occasionally useful are in cloying Millennial Marketing Language. Not just Recent, but Speed Dial.

I think the argument that streaming UX design reduces deep focus is fairly straightforward – half the time I open the app I forget what I meant to put on to begin with, and apps are in the business of keeping you inside them for as long as possible. The argument that streaming is actively disrupting music listening habits is a bit more complex. For this, I turn to Liz Pelly, who will eternally lap me as a thinker about the intersection of music and technology. In her article The Problem with Muzak, Pelly argues compellingly that music streaming platforms strive to turn music into “emotional wallpaper.”1 As she says,

“[Playlists are] also tied to what its algorithm manipulates best: Mood and affect. Note how the generically designed, nearly stock photo images attached to these playlists rely on the selfsame clickbait-y tactics of content farms, which are famous for attacking a reader’s basest human moods and instincts. Only here the goal is to fit music snugly into an emotional regulation capsule optimized for maximum clicks: “chill.out.brain,” “Ambient Chill,” “Chill Covers.” “Piano in the Background” is one of the most aptly titled; “in the background” could be added to the majority of Spotify playlists.”

Music streaming apps, with Spotify being the disruptor in this regard, advance the playlist supremacy mode of listening to music. This type of listening, as Pelly says, creates (or at least captures and feeds) a demographic of “anesthetized” music listeners more attuned to affect and vibe than attachment to particular artists. The “always-on” nature of music streaming makes chill music particularly attractive and instrumentalizes music into something that is there to optimize productivity, block out distractions. This all turns the music consumer into less an agent and more a subject – even more so than comparable modes of listening like radio, because the curator goes from an individual DJ with individual tastes to a firm looking at trend lines and maximizing KPIs. All in service of streaming platforms’ great love, microtargeted and invasive data sets.

Spotify is somewhat of a black box when it comes to its data, though. In 2020, Spotify claimed that users spent 2.3 billion hours listening to their Discover Weekly playlists. As a number, this is basically meaningless beyond conveying something very large – it doesn’t describe what market share of people listen to platforms’ playlists, what percentage of their music listening habits playlists constitute, or any other crucial data we’d need to make specific deductions. What we can see, however, is that Spotify, platforms like it, and their leaders clearly see algorithmic playlists as the future of music listening, for better or for worse. And as Pelly argues, mood playlists in particular usually appeal to a lowest common denominator logic, much like the rest of the Internet being filled end-to-end with algorithmic ‘slop’ to attract clicks. It’s all fake and hollowed out, all the way down.

Worse than that, much like Netflix, where a dominant type of content emerges because it’s easy to produce and consume, platforms naturally push creators to prioritize whatever performs best. This, in turn, homogenizes content across all platforms. Everything starts to feel the same, indistinct, because at some point, that content delivered the most appealing KPIs. But that pattern is context agnostic. People tend to passively listen to Chillwave (the same is true of passive watches on Netflix like The Office), but the data interpret their behavior as proof of popularity, reinforcing the cycle.

Ultimately, this means that music is entirely incidental to the equation, and I don’t mean this in a non-specific “the problem is capitalism, money ruins everything” kind of way. This type of listening creates new types of music listeners and influences the type of music that artists can create and succeed with, creating a flattening effect for all types of music, not just chillwave.

The knock-on effects of this paradigm are myriad.

For me, streaming obliterates the sense of ownership and rootedness I used to get from downloading music. I’m going to talk about theory now, okay? I’m going to bring a tank to a playground fight, I’m going to say “Dostoyevsky” at the house party. Every time I open YouTube Music, the app all that is solid melts into airs my music preferences. The life gradient I used to see in clear relief on my Zune account is reduced to seasonal roundups and mood playlists. I don’t really remember what I was listening to last month because it’s constantly pushed out in an endless series of library refreshes.

In fact, my end-of-year roundup told me that in 2024 I had Main Character Energy because I listened to The Prodigy, but the aggregation of my data mostly made me feel like a statistical blip in a musically textureless year (except for about a month I spent listening to Japanese breakcore, which was in fact fairly textured). This is all to say nothing (although I have elsewhere) about the egregious privacy abuses and creepy “AI” streaming platforms do behind the scenes. (Eventually, all companies aspire to the defense industry, don’t they?)

But it’s not exactly clear that this is anything more than a nostalgic yearning for my dressed up peculiarities and even if it is more than that, is it even necessarily bad? Like, get over it grandpa, you’ve got more free music than ever before, it’s all at your fingertips.

* * *

I remember sitting in front of my computer in December 2022, trying to put together a year end playlist for a friend, and finding myself bereft.

Mostly, I had just let YouTube feed me genre playlists. Not for lack of trying, but I could only specifically remember a few tracks, many of which were singles divorced from a greater album project. A whole year of music, memory-holed. The texture I used to use to differentiate epochs of my life was flattened. Crucially, this was just one area of my life that felt like it had no discernible character – outside the semi-protected world of my degree, almost everything felt flat, overcrowded, dispassionate. Paradoxically always-on and stimulation rich, but utterly forgettable and without character.

There are a few points of discussion here. Even if I could still download music off of Mediafire like I did in 2010, I wouldn’t have had time to dedicate an extra 30 minutes of TLC to each album I downloaded. I wouldn’t have had time because I was working and in grad school. Pelly’s writing about Spotify turning music into “emotional wallpaper” resonated with me, but it wasn’t quite enough to explain what had happened. Coincidentally, my work in grad school put me into contact with Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society, and encouraged me to refresh myself on another formative text, Social Acceleration, by Hartmut Rosa. Both had something compelling to say about the ‘always-on’ state of an internet-and-achievement-infarcted world.

Rosa discusses a few ways of labeling life experience. He describes the short-long experience – an experience that is short temporally but profoundly remembered, like a particularly moving moment with a loved one. There’s the long-short experience – long on the clock, shortly after memory-holed, like a long retail shift. Modernity gave rise to the short-short experience – many, end-to-end episodes of experience, felt and remembered briefly. As he says,

“Moreover, the short-short pattern could prove to be very instructive regarding the (late) modern experience of “racing time.” It is conceivable that everyday experience in contemporary society increasingly produces this temporal pattern because the episodes of experience that densely follow one another display a tendency toward decontextualization: lived experiences that are short, stimulation-rich, but remain isolated from each other, i.e., without any internal connection, and replace each other in rapid transitions such that time begins to race in a certain way “at both ends…”

Spotify’s move to turn music into permanent, always-there emotional wallpaper certainly fits this description of fleeting, contextless time. There is no endemic superiority to the incredibly peculiar and specific way I used to listen to music, but it periodized my life in meaningful ways, and I think the same can be said of music listening in general before streaming. Before streaming, available mediums themselves prevented music listening from becoming a homogenized short-short experience. Playlists were finite and crafted particularly. You could make a mixtape for your friend or buy one at an underground show. Digital playlists were usually just shared between friends, not curated by a large firm.

Even radio, the closest to the infinite, sprawling algorithms of music streaming platforms, had medium specific limits, like DJ’s tastes, airplay rights, and so on. So, paradoxically, the infinite scroll effect of algorithmic playlists shortens and cheapens the listening experience, or makes it a background to whatever extractive labor you’re doing.

Byung-Chul Han claims we live in a society of excess positivity and achievement. That is not Adam JK style, “hey buddy you tried, you’re beautiful” stickers adorned on top of poorly-scrawled rainbows-style positivity, but positivity in the sense of positive action, an excess of doing and yes, and a lack of rest and no. He juxtaposes this to Foucault’s punitive society, and in the spirit of negativity, that’s all I’m going to say about Foucault. Han says,

“The exhausted, depressive achievement-subject grinds itself down, so to speak. It is tired, exhausted by itself, and at war with itself. Entirely incapable of stepping outward, of standing outside itself, of relying on the Other, on the world, it locks its jaws on itself; paradoxically, this leads the self to hollow and empty out. It wears out in a rat race it runs against itself.”

This is the oppression of the subject-turned-hustlebro, the dude who kills himself at 32 working in finance or, more likely, getting swindled by the smash and grab schemes of the financial class. Han also calls this state “hyperattention,” a broad attention state devoted to many shallow experiences simultaneously, like Rosa’s short-short. It’s using music, one experience, to maximize productivity, another experience – end to end, ad nauseam, rapidly and polychronically. And indeed, something I said earlier reads exactly like a depressive – “everything feels flat.” It’s unsurprising then that the collapse of my passion for music happened to me while working, while in a grad degree, during one of the most isolated periods of my life.

Burnout, as in Han’s The Burnout Society, has exploded into a mental health topic du jour, though our collective response to it has been predictably feeble therapy-speak. All of this is hardly a phenomenon unique to music and music streaming, but I think the way they interface has had a profound negative impact on music listeners. Sure, we’re losing agency in life to disruption and the precarious gig economy, but we’re also losing agency as consumers? What kind of raw deal is that? When the consumer turns into the product though – as data points to sell – companies no longer need to pander to them.

An anecdote. I recall seeing a thread on Facebook asking for comedy podcast recommendations, and somehow stumbled on a comment that baffled me. The commenter claimed that he listened to all podcasts at 1.5 speed, and not only that, but it felt like a moral imperative to do so, in order to fit in as much enrichment as possible into his daily life. I was repulsed. I immediately and reflexively called the man a psycho. I also realized I wasn’t far from this in a few areas of my life too, and the same pressure grinds at so many other people. Also, the podcast he was talking about having a moral imperative to listen to at 1.5 speed was My Brother, My Brother, and Me, so that made it really funny.

* * *

One bitter winter night I was sitting in a friend’s basement studio, listening to him and some other friends jam on some jazz standards.

Unusually for that night, I decided to join them. I am a decent musician, but far from a good jazz player. The session must have only lasted another hour after I joined, but it stayed with me. It was a version of Rosa’s short-long, and after that day I kept practicing and found myself rejuvenated enough to just let myself sit down and digest a few jazz albums waiting for the next session.

Around the same time, another subgroup of friends started collecting vinyl records. I already had my own collection, and we would sit around, idly listening to them and sharing favorites. The medium – highly finite – and the context of listening – idle, not trying to build or achieve anything beyond what was currently in the room – was immediately rejuvenating, in the same way that active listening during a jam session was.

This shouldn’t be shocking – I’ve just described “having friends” and “enjoying time with friends.” But in a moment where music listening has been so heavily instrumentalized, and streaming platforms have turned listeners into commodified subjects (a dream legacy record companies would’ve surely pursued if they’d had the tools), reclaiming listening, off the grid, felt like a small but meaningful victory.

Perhaps I’ve made the stakes too high. I started writing this because I thought it was cool that the collective listening experience during jazz improvisation activated me the way listening to music used to, and now I’ve referenced three different theorists from different disciplines.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to call Spotify, and Big Tech in general, cancerous. They seek to become everything, laid naked in Musk’s ambition to remodel the flailing Twitter as The Everything App. The culture they favor encourages us all to do the same – be everything, all the time, always-on, all positivity. I don’t believe music can thrive in an environment like that. Music can’t be an instrument to optimize productivity, and it can’t thrive between trendlines bent to maximize shareholder value. Spotify’s emphasis on playlist primacy and their opaque KPI and algorithm driven structure has destroyed the means with which most artists had potential ins to the industry, eviscerating indie labels that could advocate for artists and flattening music into progressively more homogenized output. Truly, we live in the era of Content™: context free, everywhere, undistinguished.

I don’t know what the Big Answer is2, but I know that this tech business trend is unsustainable, and I think more and more people are getting tired of being always on – how could they not? Burnout is baked in. Spotify Wrapped felt less fun this year and relied on AI (including an AI podcast), just like every single other stupid vacuous app in the world as companies try feverishly to cut costs in hopes that AI will spark a genuine revolution (it won’t). This is the logical endpoint of a society that treats the arts and humanities with the dismissive contempt of “learn to code.”

What do we do, then? I haven’t escaped burnout society – an escape from this short-short, burnout mode of existence requires, in my eyes, a broad social shift away from hustlegrind mindset towards degrowth and, frankly, way less work. But we can’t put the Spotify-brand toothpaste back in the Spotify-brand tube. We can’t just reject something that has swallowed the music industry whole. Even if we all threw our phones in the fucking ocean, now Spotify prints vinyl.

I have found things that help me restore that gut-felt love for music, the one that I first let myself indulge when I pirated Franz Ferdinand’s Franz Ferdinand in 2010. They aren’t enough to kill the behemoth, but tech is flagging. AI is lame outside of making pictures of Cloud Strife using a Buster Cigarette. The algorithm is losing its incisiveness. I hope that the tech and business sectors’ broken promises will offer the opportunity for music lovers and artists to build something real on the wreckage – something that brings the joy back to listening and finally gives artists the deal they deserve.

— —

1. Anecdotally, I’ve found this to be true. I still remember a snowy day in 2010 where I listened to track two, “Teddy Picker,” on Favorite Worst Nightmare on repeat, a lonely drive through Philadelphia in 2016 listening to RTJ3. When streaming, it’s not uncommon for me not to know the name of a song or even the artist.

2. Getting too off topic: China has laying flat (tang ping) and let it rot (bai lan). The US has Quiet Quitting. Han quotes Nietzsche, “All of you who are in love with hectic work and whatever is fast, new, strange—you find it hard to bear yourselves, your diligence is escape and the will to forget yourself.” If you believed more in life, you would hurl yourself less into the moment. But you do not have enough content in yourselves for waiting – not even for laziness!

— — — —

Connect to Atwood Magazine on

Facebook, 𝕏, Instagram, Threads

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine