In his sophomore LP ‘Orca’, Gus Dapperton forgoes lovestruck odes for an honest, bittersweet take on our less forgiving emotions.

Stream: ‘Orca’ – Gus Dapperton

I think I’ve seen my life flash before my eyes a lot in the past year or so.

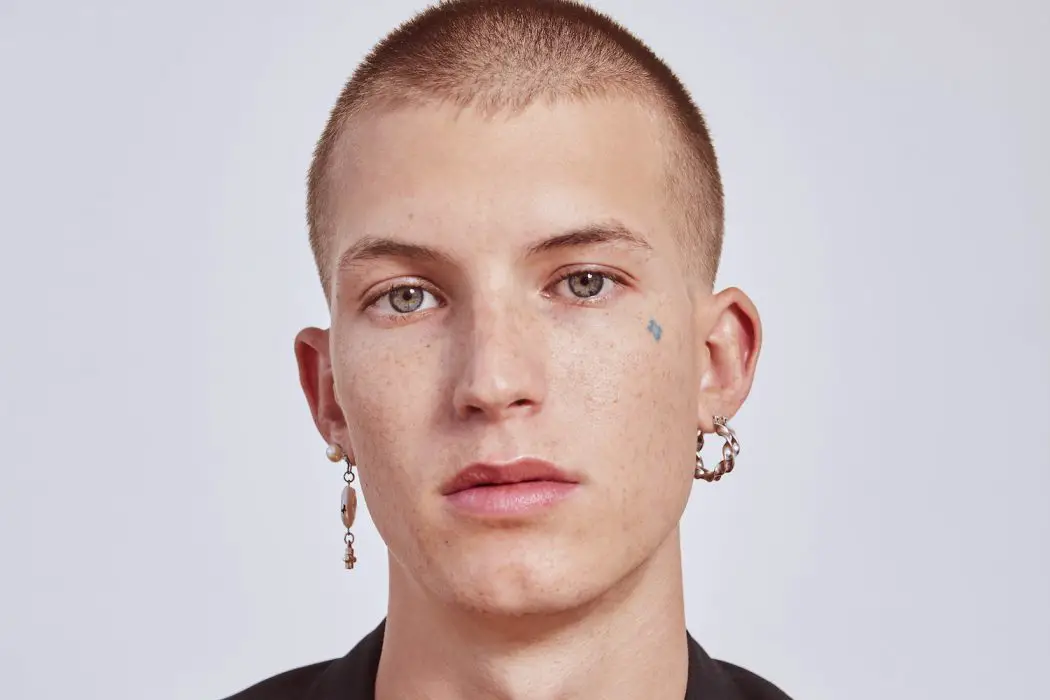

Gus Dapperton is speaking to me from his Bushwick apartment. For our talk, he’s traded in poppy colors for casual grayscale streetwear, opting for an airy hoodie, a black cap, and one silver double-hoop earring. It vaguely evokes his beginnings in the New York hip-hop scene. “We got a loft space in Brooklyn,” Dapperton tells me, “and so I have a proper studio here, which is nice. But in the past it’s always been just a bedroom setup. A couple speakers, microphone, and interface.”

Gus Dapperton was born Brendan Rice in Warwick, NY, a conservative-leaning town he describes with the term “structural functionalism,” a place where “they fear change so much that they stick to these traditional values, and there’s just this cycle of it.” In his hometown, he explains, people would go to college in upstate New York and come back and teach, “which is cool. My mom did that. She grew up in Warwick, born and raised there, went to Cortland, came back as a teacher. And I think that’s super awesome and my mom’s a great person. But I didn’t want to do that.”

Now, after couch-surfing in his early days in the city, sharing bills with rappers and folk musicians alike, Dapperton has emerged as the evergreen it-boy of indie pop and swagger Lorem aesthetics.

He has his own studio setup in Brooklyn and prefers to go by his stage name. His given name, Brendan, would appear lyrically in his music for the first time in his recently released sophomore album, Orca (“His name is Bren, don’t forget / an irrational lament,” “First Aid”). “I sort of referenced those two eras of my life. The start of a new era being me, Gus, this is my music, this is how I’m gonna express myself for the rest of my life, and Brendan being someone who is more neglected and discouraged from that.”

“Adults aren’t gonna encourage me to play the guitar if I suck at the guitar, and they’re not gonna encourage me to play the piano if I suck at the piano,” he elaborates. “I pretty much did suck at all those things, but the one thing I did have was I had a vision, and I knew how to accomplish that. And the guitar and piano and singing and production are just all tools to get one vision across. I think it’s hard for adults to see that, and so I always resented that a bit and regretted that a bit.”

You never let them get to you

You never let them get to you

You never let them get to you

I always let them get to me

I don’t know if I’ll last until tomorrow

It’s such an arduous task to always bottle it up

If you could lend me a breath that I could borrow

Then I could give it my best and try to swallow it up

– “Bottle Opener,” Gus Dapperton

An emotional aperture with a pop-rock sheen, opening track “Bottle Opener” acts as a kind of prologue to the psychological portrait of Orca. With elements of acoustic guitar, symphony, and choral incantations, the song is like a gradually brightening light, ready to spill over. Each repetition of “You never let them get to you” and each admission of “I always let them get to me” disarm us. On Instagram, Dapperton describes the music of Orca as conceived solely by the heart. “There was no rhyme or reason except that I would let its condition overcome me. I am just the mouthpiece,” he writes. Performer as vehicle, vessel, or bottle. We’re asked not only to listen to the music, but to really hear its content. Clocking in at just over two minutes, “Bottle Opener” is the only track that begins immediately with the joint vocals of Dapperton and his sister Ruby Amadelle (though she will reappear often, a continuous presence in the album). It feels, in some ways, like an initiation.

In a previous statement, Dapperton spoke of unbalanced touring experiences that gave rise to heavy alcohol and drug use. “On this album I’ve been able to reflect on more personal struggles I’ve had, and so I guess I made this music to put my words and feelings into a physical form as sort of a self-release,” he says.

Orca, instead of waxing sweet poetics about love, crushes, jealously, or feeling “fa-la-la-la” (“My Favorite Fish”), is about a lone emotion, of a darker nature, sprawled out across ten songs. “It’s more of one feeling, of feeling in my head and feeling isolated and feeling lost in the world. Once I started exploring it that way, I really thought it was important to keep going. And it’s something I never really had done before.”

Dapperton often explains his songwriting process in terms of a “divulging.” There is a sense that the way he writes is a way of making himself known. In tracks like “Antidote,” lasting guitar and bass strums seem to suspend time. With a slow-moving, sedative pace, looping beats, and teary-eyed articulations of “But you said, ‘What about our past?’” “Antidote” takes on the confessional quality of a one-man show.

“First Aid,” similarly vulnerable, deals with depression, while “Bluebird,” one of the more freewheeling tracks on the record, is all energy and touching melodicism with an old-world charm. Third track “Post Humorous” is a pun off the word ‘posthumous’ and about someone who treats life like a joke, because they feel like they have nothing to lose. A fan of comedy, Dapperton says that he’s always the one making jokes, especially around people he’s comfortable with. “I’m obsessed with humor,” he says. “I love laughing. I love when my mouth hurts from smiling so big, you know?”

I don’t ever wanna let you go

You’re the only one who lets me in

But every time I try to hold my own

Yeah, I can never seem to get a grip

And I don’t ever wanna give you up

I always say I’ll get ahead of it

But every time they try to fix me up

I get addicted to the medicine

– “Medicine,” Gus Dapperton

It’s more of one feeling, of feeling in my head and feeling isolated and feeling lost in the world. Once I started exploring it that way, I really thought it was important to keep going.

To Dapperton, “Medicine” is the most important track on the record. “It talks about how someone is self-destructive because they know that they have a lot to fall back on. They know that the consequences of their actions aren’t great…and they get addicted to the healing process.” Dressed up in pomp, “Medicine” begins with a grand piano theme and heavy reverb. “We’re the product of a crowded youth,” Dapperton sings, all radiant and just a bit melancholic. There’s something evanescent about the song, like a soundtrack you’d imagine hearing at the cinematic denouement. And it makes you really want to cry.

“I think a lot of this album is just, it’s kind of like the phrase seeing your life flash before your eyes. I think I’ve seen my life flash before my eyes a lot in the past year or so, and that goes back to my youth and what I did to get to this point. I think that I don’t regret any of it or resent any of it even though I used to. I used to be like, I wish I wasn’t so discouraged by my community and my peers from doing the things that I do, and pursuing art in the way I wanted to…But this album is me reflecting on the fact that if it didn’t happen that way, maybe I wouldn’t be so passionate about this or the things I do. I think…it encouraged me to get out of that town, it encouraged me to leave, it encouraged me to go explore the world.”

Please don’t take me back

Though you said that it’s okay

You’re under attack

Almost every single day

– “Antidote,” Gus Dapperton

In the album cover for Orca, Dapperton, who’s generally handled his persona with great panache, stares us down in a tussle of red hair that seems motivated more by inner emotion than style. Parted down the middle, it accentuates the visual duality of the artwork: one-half of his face is in the shadow; the other is in the light. “It’s supposed to be two halves to a whole,” Dapperton explains. “It’s supposed to be you can’t understand some things, mental health, based on their physical appearance.”

Three crosses are stamped to the upper-left hand corner of the cover art, and they appear on the single covers for “Medicine” and “First Aid.” Dapperton refers to them as first aid signs and as plus signs: they are meant to represent hurt, heal, and help, though their religious undertones are hard to overlook. While Dapperton isn’t religious, he explains that he’s always been, in a way, jealous of the community of religion, of “people who can go pray and hold something close to them, hold an icon close to them that make them feel closer to something positive and to something safe.”

Dapperton has a first aid tattoo, and his sister and bassist also share tattoos based on Orca. The album is, in some ways, born out of a collective spirit. “A lot of these songs are really personal to me, but it almost makes them more personal having all of these different voices on them that are people that are close to me, people that have experienced a lot of these same things that I’m experiencing and have been there through this time.” The choice of Orca as the album name comes from orca whales, animals that experience strong emotional distress when they’re separated from their family and kept in captivity. “I don’t think I could’ve toured so extensively if it wasn’t for my sister being with me, my best friend Tommy, my best friend Ian, and my band. And when you’re separated from those people, you know, it can be tough.”

“I think it all means something to us, although we had different parts in it,” Dapperton says. “It all means something to us.”

I’ve got no car

I’ve got no ride

I’ve got no head

To hold up high

But you’ve got heart

And, boy, do you got drive

It’s not that far

It’s worth a try

– “Bluebird,” Gus Dapperton

For Dapperton, the making of Orca was a deeply therapeutic process, and though he has written many more tracks since, he is no rush to pursue another project straight away. “A lot of times people are asking where I want to be five years from now, and I’m like, honestly, my whole dream growing up was to move to New York City. Ever since I was able to do that, I’ve accomplished my dream.”

A pin-sized, blue first aid sign tattoo rests on Dapperton’s upper left cheekbone. He had blue stitches in the same spot a couple years ago. It’s a rare hint of color amid the monochromatic outfit he’s chosen for today.

“I have a lot of faith in humans and progress, and I wanted to come up with something that is more universal for what my beliefs are,” Dapperton explains, when I ask him about the meaning of his tattoo near the end of our conversation. “I believe in outward expression, and I believe that in order to have emotional highs you have to have emotional lows. I believe that humans can learn from their mistakes, and I believe in love.”

I believe in outward expression, and I believe that in order to have emotional highs you have to have emotional lows. I believe that humans can learn from their mistakes, and I believe in love.

— —

:: stream/purchase Orca here ::

— — — —

Connect to Gus Dapperton on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Jess Farran

:: Stream Gus Dapperton ::