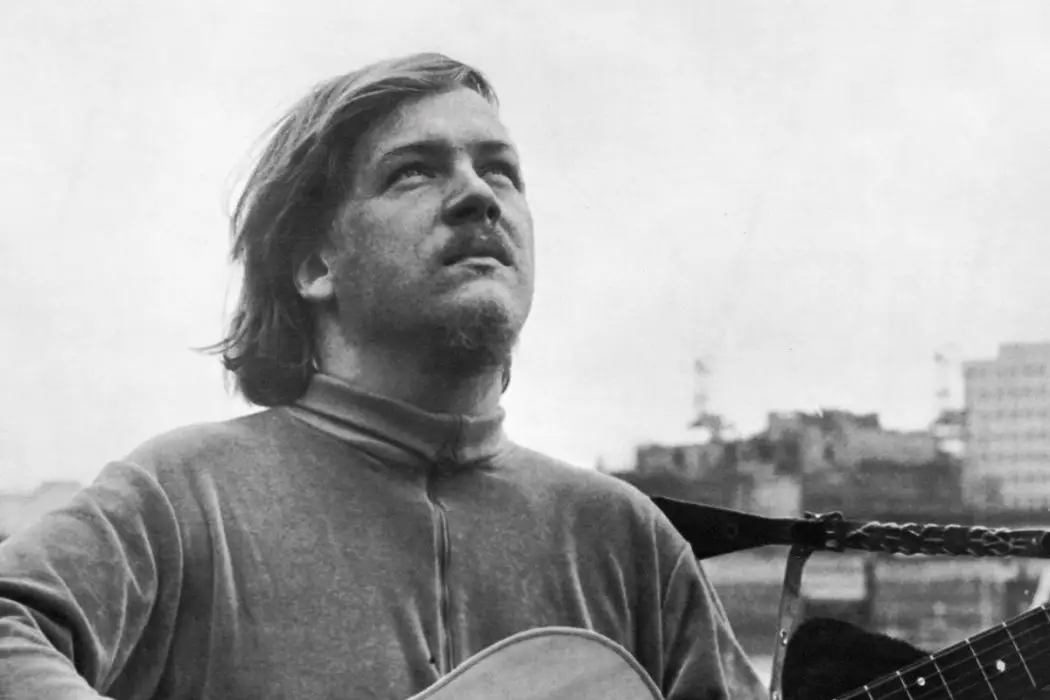

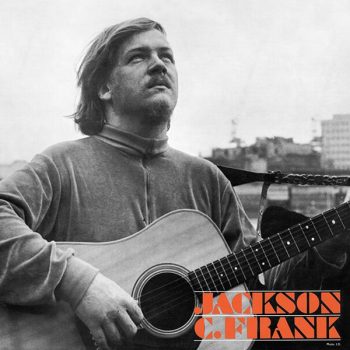

An in-depth listen of the 1965 self-titled album by Jackson C. Frank, one of folk’s most brilliant and forgotten records.

Listen: ‘Jackson C. Frank’ – Jackson C. Frank

In the field of creative endeavour, anything that can confuse us totally is generally given over to rejection or abject praise.” This quote appears in the back cover of Jackson C. Frank’s self-titled long-forgotten folk masterpiece from 1965. It’s the first sentence in a long text written by Frank himself as a sort of introduction for anyone that is about to listen to the ten songs contained in the record. His words continue for several paragraphs shifting between poetic rants, personal tales and philosophical explorations about the human expression. It’s hard to follow exactly what he is trying to convey but the text serves as a perfect presentation for the cryptic run-down beauty that awaits inside the album. In another sentence he brushes over his relationship with his own music:

Songs that I write aren’t mine to admit to. They dwell a little too heavy on the grey area behind my eyes to become my friends, and with that pat explanation you can judge them yourselves.

More than an introduction, it reads like an artist questioning what the act of recording and releasing music is all about. How can compositions that come from such deep experiences of pain and struggle hold their meaning once they are packaged and sold? Is there an intrinsic value to art regardless of how many copies are bought? And what if its true message is never really understood by the audience? These dilemmas were particularly interesting in the old-school music industry in which there was only one path to “making it”. You were either on a label and on the radio or you weren’t at all.

Jackson C. Frank fits the archetype of the shy performer torn between the shadow of failure and the weight of success. Two poles so well represented by Nick Drake (who we will return to in a bit) and Elliot Smith. One second-guesses how good his music is, discouraged by the lack of conventional milestones of success; while the other is never able to trust his songs, always suspicious that they’re just being used by the industry. Either way, the purity of creation is lost; the relationship between writer and song, broken.

In the hall of tortured singer-songwriters (as tragic as Drake’s and Smith’s fates were), Jackson C. Frank might just have the saddest life of all. However, that’s not what we’re here to discuss. You can read his biography on Wikipedia and pretty much any other article written about him. It’s a heart-breaking story of childhood trauma, mental health issues, and just straight up bad luck but in it there’s one particular day that ‘shines like silver’: The day in July 1965 he recorded his one and only album in a studio in central London with a young Paul Simon financing and producing the session.

The record begins with “Blues Run The Game”, one of the smoothest openings to an album you’ll ever hear. Much like in Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” or “Place To Be”, the combination of chords and melody are enough to transmit a deep sense of longing. It gets you into a feeling straight away and then the lyrics hit like a punch to the heart. Frank takes a simple catchy phrase and turns it into an inescapable truth: that no matter where you go ‘the blues are all the same‘ and no matter how much you try to break even in love and life ‘the blues run the game‘. It’s melancholic and comforting in the way that only very few great works can be.

“Don’t Look Back” is a protest song that references the death of Medgar Evers, an African American civil rights activist murdered by a white supremacist in 1963. The theme rings painfully true and current today but the tune has that unmistakable idealism of sixties counterculture. In a parallel universe it could have easily been sung by Richie Havens during his opening set at Woodstock. This is the only political track in Jackson C. Frank, which for a folk record at the time seems strange. However, the first half of the album is still very much something you’d expect from an American singer-songwriter living in London.

There’s “Kimbie”, a traditional piece rearranged by Frank with easy flowing and mesmerizing vocals. Followed by “Yellow Walls”, a powerful song with an all verse structure that once again showcases his brilliant lyricism:

No one knows me

In the morning

No one sees me go walking by

And if I listen while no one answers

The winds can only echo a goodbye

Side A finishes with “Here Comes The Blues”, which lightens the mood with mellow riffs but hides a darker message about depression and addiction beneath its bluesy sound. The first five songs have a lot to unpack, but only hint at the depths that the album will reach on Side B.

The sixth track, “Milk And Honey”, has a mysterious and gloomy atmosphere. There’s a version of Nick Drake covering this song, which was included in a compilation of demos and rarities. It sounds like a home recording and starts with Nick saying “Let’s see.. What could I do… what would be interesting”in a funny voice before jumping into a beautiful arpeggio that would fit perfectly in one of his studio albums. There’s three other Jackson C. Frank covers in that same compilation and listening to Drake play them makes it clear just how much of an influence the American was on the Englishman, perhaps the biggest.

I don’t pretend to be able to explain the genius of “My Name Is Carnival”, a track that reaches near Dylan levels of rhyme, poetry and delivery. One could spend a lifetime interpreting its symbolism and as with so many Dylan songs, once you think you have a grip on it, it slips away again, its meaning forever changing. The strange mythical imagery rides a galloping melody that doesn’t leave time to really process what has just happened. It is the type of song that is meant to be experienced more than understood.

At this point in the album, there’s a tension already building and it doesn’t help that the next words are the following:

I want to be alone

I need to touch each stone

Face the grave that I have grown

I want to be alone

A slow song with the spirit of an old English ballad, it’s hard to tell if “I Want To Be Alone” is about making peace with death or loneliness. Perhaps both. Another text by an author only credited as “C.G.J.” in the back cover of the album interprets that the lyrics are trying to express that ‘one must be alone by choice or he cannot give of himself to anything or anyone’. Combine that with a haunting delicate voice and it’s enough to leave you shaken.

This streak of three songs from “Milk & Honey” to “I Want To Be Alone” reminds me in a weird way of The Cure’s Disintegration. There’s a point in that album when I can start to feel claustrophobic with two songs still remaining. After such an intense row of emotions, the final tracks feel like a comedown. That’s exactly what happens here. Jackson C. Frank poured a big chunk of his soul into this record and gazing at it can be draining. By the end, you sort of forget the songs and are just left with a raw human connection that sticks with you long after listening, like a balloon tied around a children’s wrist.

After writing this I kind of understand why Frank felt the need to address the listener in the back cover. I imagine he was anticipating that connection, not knowing who would be on the receiving end, but aware of how vulnerable he had made himself in the songs, and so trying to justify why anyone should lend their time to that exchange. Recorded music (especially an album as personal as this one) becomes a ghost. Once it is out there it doesn’t care about commercial success or failure, it’s just always ready to manifest itself whenever someone summons it.

I like knowing that Jackson C. Frank was recorded in just half a day because it makes it easier to grasp the idea that there was a real moment, an actual time and space in which the artist lost himself in the song and nailed the take which was captured by the microphone and caught on tape. Rare and forgotten albums have the special quality of making incredibly evident just what a weird magic spell it is to be listening to them fifty five years later, in another format, six thousand miles away. And I like to believe that Jackson C. Frank knew that even then. This is the final sentence in the back cover introduction; he is referring to the songs:

“If they communicate to you any measure of something valued, or remembered, or recognised in the streets you have just walked, then they are a success within very limited qualifications; that is, you and I have met once more…”

If you have made it this far, I invite you to pay a visit to the ghost of Jackson C. Frank. Or at least the ghost of a certain productive day in July 1965. Before it all went bad.

— —

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

Jackson C. Frank

an album by Jackson C. Frank