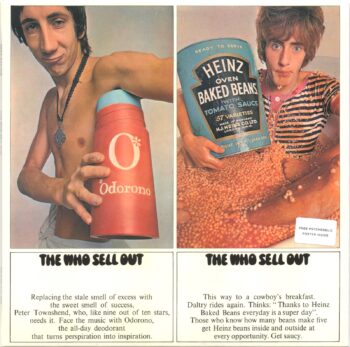

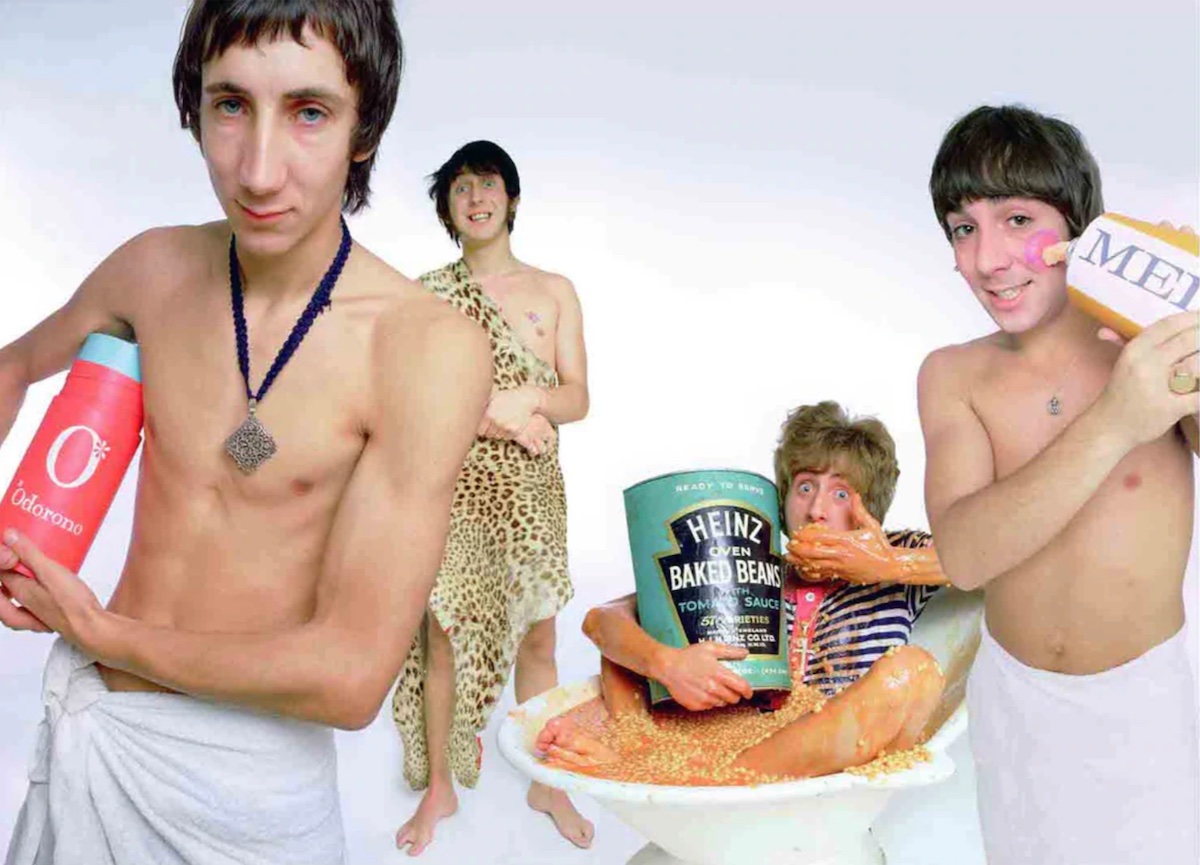

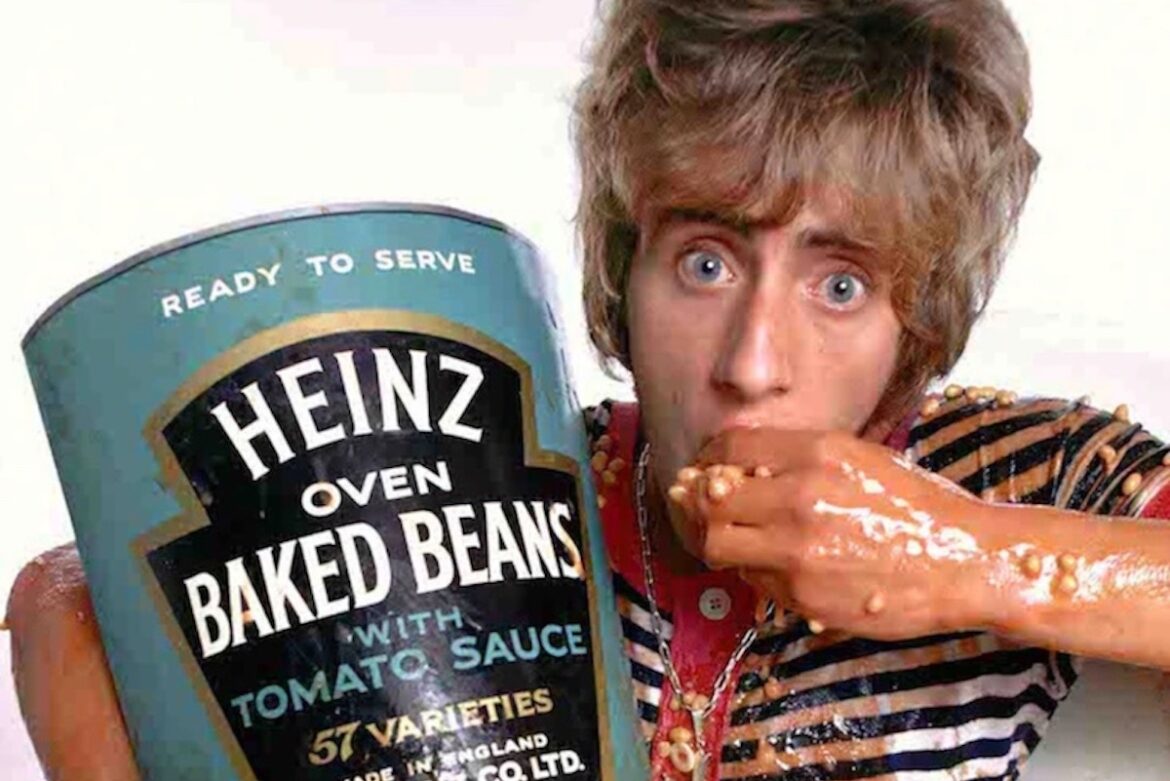

The Who, bombastic chroniclers of rebellion and repression, never addressed society’s struggles more forcefully – or efficiently – than in “Heinz Baked Beans,” the fifty-nine second opus from 1967’s ‘The Who Sell Out.’

by guest writer Robert J. Binney

Stream: “Heinz Baked Beans” – The Who

With the recent Broadway run of Tommy and a ballet interpretation of Quadrophenia prepping its London debut, Pete Townshend’s grandiloquent ambitions to elevate The Who’s legacy continue unabated.

There were rock operas – and operatic rock (Google the original Nirvana) – before any deaf, dumb, and blind boy played a mean pinball, but there’s never been anything that can truly compete with The Who’s own “Heinz Baked Beans,” from 1967’s ersatz pirate radio broadcast album, The Who Sell Out.

Some might dismiss bassist John Entwistle’s effort as less than a song. A mere novelty.

They’re wrong. It’s one full minute of tuneful perfection.

“Heinz Baked Beans” has your mini-operas and bloated sagas beat. Sure, you can have four album sides of some git popping pills and not getting laid, but Quadrophenia lacks genuine dramatic conflict – what’s Jimmy’s motivation? What obstacles are truly in his way? He sings, “Is it in my head?” Yes, it is, Jim. Now get on with it already!

In “Heinz,” you have clearly defined struggles cutting across generations of family dysfunction. On their face these struggles should resolve easily, yet still they escalate. Hostility remains buried as characters ask simple questions; the listener must parse the dialectic tension between the melodic whimsy and the tragically headstrong family. For an added bonus, there’s Keith Moon attacking a bass drum with the reckless abandon denied the song’s protagonists.

We’re first introduced to the Young Lad. He’s nameless (“Billy,” “Jimmy,” “Tommy”), because he’s all of us. He’s a good boy: He’s home when he’s supposed to be, he’s well-mannered, he minds his teachers – isn’t that the ideal? He upholds his side of the social contract, and in return all he wants is to know what’s for tea.

His friends – those whom he was just outside playing footie with – have all gone in for their tea. They will enjoy nice cakes, or maybe chocolate and lemon biscuits. Some – the poncey ones – will have those little crustless sandwiches. It’s always a surprise, and always a welcome one. So it’s perfectly natural for the Young Lad to be curious what’s in store for his tea.

There’s a small part inside him that’s disappointed when he doesn’t get sweets like the other boys, but he’s still too young to understand why he’s denied such basic pleasures. Some of the others wear finer, fancier, cleaner clothes – but none of that matters. At his age, a roof overhead and food in his tummy is all he needs. Yet. Still he yearns for knowledge. For certainty. Stability. Exactly what’s withheld, by Mum, the very woman who gave him life. But here he is.

He wants to know what’s for tea, and she’s not spilling.

* * *

Then there’s the Husband. He’s resigned to being ignored all day, but it shouldn’t be that way in his own home. Not from his wife. At the plant, he’s surrounded by the tough steelworkers and dock hands that bullied him in school. He tends to the accounts, sheltered in the office; he can mostly avoid such rough characters, but can’t ignore them completely.

Okay, sure, he’s intimidated. They’re not just blokes, they are Men. Real Men. They go to the pub and they drink and they laugh and they fight and they wench. He worked so hard to get away from a life like that, yet he can’t help but envy it a little. Does he want to be one of them? No, not really. Of course not.

But when he comes home, he wants his needs to be met. He’s not a demanding man – a clean home, a dutiful and quiet son, maybe “Coronation Street” or that new programme about the prisoner on the telly. He once pictured a larger family, but that would involve he and his wife, well, you know…

One thing he will not abide at home is ignorance. Whether that means being kept in the dark about crucial domestic information, or whether he himself is being ignored. So when he asks what’s for tea, he – by right as Man of the House, as the breadwinner – he should get an answer. He should not have to repeat himself.

He’s home, right? What more does this woman need? He brings her everything – he pays the mortgage, the license fees, he even fixed up the closet for her bloody father. He doesn’t understand why she’s like this. He doesn’t mean to be stern, but…

But here he is, standing in what passes for a foyer, he’s peckish, and he wants one thing: To know what’s for tea.

And to not have to repeat himself.

So, two things.

* * *

About her Father. Sure, now, he’s a doddering old man. This is how we treat our heroes.

He was at the Somme in 1916; when not gasping for air or struggling with the bolt-action on his Enfield, he was buried under the bloody carcasses of friends and brothers, hoping no one would notice he’d pissed himself. For this, he was given a piece of tin on a ribbon and sent back out – to Arras, where he knocked down doors to homes much like this one, rooting out Germans just as young and scared as he.

And for what? He came home and his best girl had married. He joined the merchant marine, abandoned on some coast after a drunk Belgian let go of a windlass and crushed his left arm. Tried to make it as a bootmaker, an impossible task for a cripple, so he set to work as a shopkeeper. He married the idiot butcher’s idiot daughter only after he knocked her up one night behind the Owl and Gloucester. She lost the baby, but it was too late. Vows had been made.

When the Germans came again, he knew what he had to do. He still shook in terror – and still soiled himself – recalling the Great War, but he felt this overwhelming need to protect his growing family. They had a daughter now, and she was the absolute light of his life. Thanks to that Belgian’s carelessness, he was rejected for active service, but still he was patrolling neighborhood streets every night, making sure lights were out and doors were locked. London got the headlines, but Jerry bombed all of Britain. Nowhere was safe. There wasn’t much he could do, other than stand there in his steel helmet and blow his whistle, but that was enough. A patriot through-and-through.

The worst of war, to him – whether choking on gas in the trenches of the Western Front, or inhaling the detritus of his hometown’s bombed-out pubs and dancing halls – was never knowing what was next. Even when he was sailing the Atlantic between the wars, as hard as that life was, he knew what to expect, day in, day out.

And now? He has no clue what was happening. One day his Martha was gone and he was living in a closet. This so-called man that married his little girl – he was nothing. He pretended to be so high and mighty, but he wasn’t much at all. Sure, his daughter tried to take care of her family, but she wasn’t ready. Martha hadn’t taught her how to be a wife, or how to be a mother.

And now here he was, broken body wrapped in a blanket that smelled of cheese, and mildew, and piss. All he wants to know is that he will be safe. That someone is taking care of him.

Truth is, he doesn’t care what she serves. He’s grateful just to be having tea. But that fear of the unknown, of a bleak future deprived of all true satisfaction, stared him in the face. If only his daughter would comfort him, tell him what they were having for tea, then, he suspected, things would be alright.

* * *

Personally, she has had it. All her friends are out in Swinging London, having the time of their lives.

They went to secretarial school, she got pregnant. They wear boots and dance at go-go’s and smoke American cigarettes and laugh; she makes tea. At home. If it weren’t for that one night she hiked up her skirt, she’d be with them right now. More likely, she’d be Mrs. George Harrison, taking tea at the Savoy or maybe even Buckingham Palace. She heard they did that.

But here she is, trying to make the best of it. With a leaky kettle and an oven that will never be clean – everything tastes vaguely like kippers – but she’s trying.

And they keep asking her – what’s for tea? What’s for tea? What’s for tea?

For heaven’s sake. It’s not like she can just whip up a cake – they can’t afford to waste eggs or butter like that! And cucumber sandwiches? You want me to do what with the crusts?

Has no one heard of fiber? Protein? The other kids don’t eat vegetables because they can afford to scrape them into the bin; she can’t afford fresh greens at all. It’s not easy to be economical and still provide a nutritious snack.

That brat she once suckled runs in, tracking mud on the floor she just mopped. That idiot she married, smelling like stale office sweat and flat beer – she doesn’t mind his going to the pub on the way home, but she resents wasting money. And always asking the same thing, over and over and over again. And that lame, withered shell who treated her mother so poorly? She tries to take care of him, but he just sits there, shaking and pissing himself, drool running over his lip.

But she has her radio, her only escape. The sounds of far-off places. Liverpool. Chicago. Wandsworth.

Standing here in the kitchen, she can almost hear it. First a horn, plaintive yet inviting. Then the horn again and a banjo, an amuse-bouche. And drums! Now a full brass marching band! Building and swelling, punctuated by the boom of a bass drum surely bigger than her couch. The sound of jubilee. Celebrating her. Her motherhood. Her dedication. Crescendoing in an explosion of joy, recognizing and validating the sacrifices she makes to feed and protect three generations – the Heroes of Our Past, the doldrums of the Present, and the Hope of the Future.

And yet they interrupt this parade, this cavalcade of horns and elation, to ask the same question, over and over and over.

What’s for tea?

* * *

The wide-eyed optimism of Youth. The not-so-casual disdain and misogyny of the Middle Class.

The disposability of the sacrifices of our Elders. The tragic invisibility, vulnerability, and powerlessness of the Modern Woman. This is the tableau we are presented on the second track of the LP.

The drudgery. Tragedy. Hunger, the barely controlled rage at demons personal and universal. Are these the stories of postwar England, nearly 60 years ago, or of today’s America?

It’s turmoil and prescience, brought into stark relief and all-too-honest reckoning by The Who.

Maybe it’s only when Pete puts down his guitar – picking up his banjo here – that he truly invests his emotions, his humanity, in the music. Or maybe, liberated from songwriting duties, he can forge a connection with the rare song penned by his mate. Maybe Keith, limited to just one piece of percussion, allows himself the freedom to express the wayward spirit that illuminates us all. Maybe it’s the complete lack of restrictions on John’s horns and orchestration that expands this micro-opus and, within its perfect 60 seconds, contains multitudes.

But there she still is: Mum. Darling. Daughter.

I’ll tell you what’s for f*ing tea, she wants to scream. I’m opening up the god-damned tin already.

Heinz Baked Beans!

— —

Seattle-based screenwriter Robert J. Binney has written about Joe Strummer, James Bond, joyriding with the Salt Lake City police, and his relationship with President Jimmy Carter (though not all at once) for the Los Angeles Times and other fine publications. Most recently his fiction was published in Down & Out Books’ anthology The Killing Rain.

— —

:: connect with The Who here ::

— —

Stream: “Heinz Baked Beans” – The Who

— — — —

Connect to The Who on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© David Montgomery

:: Stream The Who ::

© David Montgomery

© David Montgomery