Justin Bieber – Capitalism and Pop-Culture is an opinion-based article that tries to explain how popular culture is a byproduct of capitalist endeavours. It also tries to explain why Justin Bieber is stunningly reflective of our cultural practices and hence, the biggest representative of our popular culture. I wrote this article because I felt that we were overlooking our social contexts when we were essentially trash-talking our popular culture. I wondered if this dismissing attitude came about as a way of ignoring social responsibility; were we already aware of how we lived and didn’t want to confront it, when it manifested in pop culture?

by Adrija Ghosh | Calcutta, India

— —

Our popular culture is as reflective of our taste and cultural practices as our nation-state’s democracy. The democratic structure requires representatives, and pop culture requires icons. Undeniably, Justin Bieber is one of the most visible pop icons of, at least, my time. Our popular culture is replete with commercialisation, de-sensitisation and misrepresentation, and perhaps then the biggest hits that come out of it are so as well.

It’s easy to say that the media is spoon feeding us, but like Althusser had theorised there are a lot of apparatuses, otherwise, in function here. There is an anxiety for resources and how we can access them. It can be anything from cultural or capital, to economic. Think Zelda Fitzgerald giving the financial boost to Fitzgerald and his aspirations for inclusivity in the cultural circles of the ’20s – and what did he even write about? Debauchery, money, insecurities, infertile human relationships. His reality.

We haven’t been turned into bricks solely by external agencies. We have enough agency of our own to shrug off any form of social responsibility. This trial and error to achieve a more wholesome balance that is tolerant, self-critical instead of being self-indulgent can’t be achieved unless we realise that we are too damned complacent. We resist change. We are comfortable in claiming individual taste, and can’t criticise ourselves because that involves our time somewhere else other than pursuits of social, economic hierarchy. We are okay being rigid. We are okay when we are supposed to be questioning while retaining compassion.

So, maybe the “cultural paralysis” of recent times is reflective of how people would rather be ignorant and caught up in the bygone eras; to insult and dismiss contemporary popular culture at face value, but not confront why our recent pop culture is the way it is.

Your, mine, and our popular culture is reflective of what we are consuming as a society. There are more songs about money and hypersexualisation, because this is a money-obsessed society, steeped in capitalist interests that is mainly propagated through the ads you consume. It’s a form of self-fashioning. We can listen to the subversive, pop culture of the past decades, such as Morrison, Joplin, Presley, Hendrix, The Beatles, Hendrix and we are willing to analyse their cultural, socio-political contexts, and assume ‘class’ or refinement in taste because they’ve been declared as classic owing to time. When Cobain did what he did, how many people took him seriously? When Michael Jackson became an icon, why did people try to reduce his credibility as a performer?

The first vehement contestation would be, that he’s not a part of “your” popular culture because you don’t ‘listen’ to him. I wonder if a generation’s popular culture can be located in a time that it does not occupy.

Isn’t our popular culture a representation of what we, as a generation, are consuming? Our popular culture is fueled by narcissism, self-fashioning in the virtual reality. Haven’t we collectively forgotten about social responsibility? When we are preaching to be “woke,” “politically correct,” and “aware,” how much is it to educate our immediate peers and family, instead of maintaining a carefully curated image?

If you listen to a particular genre of music, why hasn’t your “taste” been an influence upon your immediate peers who are perhaps listening to something you degrade? “Taste” is a social construct. It is reflective of your “culture,” which is different for each class. Your “culture,” your “taste” become testaments to your accessibility – your privilege; your class-sanctioned normative. Your idea of the cool, of the awareness becomes a force of Othering.

I was in my seventh grade when I first encountered the pop phenomena that Justin Bieber would be. It was one of his covers on YouTube that I came across. Then he released his first album. Then “Baby” happened, then the following World Tours, the teenage angst, the arrest, the sabbatical followed. He came back with “Sorry” and the world grudgingly, perhaps drunkenly, danced to his tunes once again. People have always been dismissive about this 23-year-old Canadian singer. They don’t consider him to be talented. His music is relegated to the people who have “bad taste” in music. He has been consistently criticised, misgendered, ridiculed, undermined. He himself has consistently made a lot of mistakes that perhaps, are characteristic of his age. But, all this is rhetorical. As much as the world dislikes Justin Bieber, he is never invisible. People are always talking about him, passing judgement… you know what the story is. You never stop discussing him. He is, after all, a huge representation of our popular culture.

How does it reflect the society you are located in? Well, give a 14-year-old child, who is ambitious for social mobility and economic development, the amount of money, endorsement, attention you associate with pop-culture, and what happens? Justin Bieber becomes an example of what this money-driven, American dream-chasing society can be. You socialize a kid into the context where he becomes a machine that perpetuates wealth, take away the normalcy of a teenager, and you get a troubled child. Bieber sings about money and women, he exoticises, he shows off, because that is what we as a society are doing: Objectifying women, appropriating others when necessary to our convenience, and chasing the good old paper. Success has become about how much popularity one has, and how it is reflected through the commodities you use. Think Marx and his idea of commodity fetishism.

We created a Justin Bieber. He became the first popstar of the social media generation. Don’t deny your popular culture, because then you’re perpetuating the ideas you so ideally oppose. You turn a blind eye to your popular culture and it gives you byproducts that you can’t claim, because you never had the courage to fix the flaws, to accept the course it’s taking.

So, what could Justin Bieber do? He took this harsh judgement and decided to dismiss the world as it dismisses it, and continued what he wanted to. He doesn’t have to be responsible for an audience that refuses to see how ideologically flawed it is; he can just make money. But he is still doing positive things, bringing about positive changes. He’s doing his part. You, perhaps, are doing yours. All of us have let Capitalism trick us into believing in the invisible hand. Well, Adam Smith was wrong. Unless we look beyond ourselves and our individual contributions, bubbles, we cannot improve ourselves as a community or as a culture.

It is our popular culture. If we want something more from it, we need to make it more accommodating of all kinds of narratives and languages, the unheard and oppressed more than others. Maybe we wouldn’t hate Justin Bieber so much if we could see that he’s singing about his reality, which is money obsessed, superficial and shallow. Maybe that’s why he, too is inclining towards spirituality to understand his context better.

Analyse your ideology, see what kind of life you live and what kind of life you want – what are you running towards? – and then see if it has resonance with your popular culture. If it does, then the fault is not without, but within.

Popular Culture exists because of Capitalism. You follow the contemporary trends, and it becomes a part of your consumption and your social context. One singer isn’t the representative of the entire popular culture, but all of our perspectives, lifestyle, and desires, are.

— —

:: about Adrija Ghosh ::

I am from Calcutta, India. from Calcutta, India. I am currently pursuing English Honours at LSR, Delhi University. I am an enthusiast of indie rock, and the 60’s-70’s. I have been heavily influenced by the Lost Generation and the Beats.

— — — —

photo © Def Jam Recordings

You May Also Like….

Understanding the Importance of Father John Misty's 'Pure Comedy'

by Mitch MoskSuccess and Sacrifice: Cold War Kids Discuss 'LA Divine'

Editorial: Justin Bieber, Popular Culture, and Capitalism

Justin Bieber – Capitalism and Pop-Culture is an opinion-based article that tries to explain how popular culture is a byproduct of capitalist endeavours. It also tries to explain why Justin Bieber is stunningly reflective of our cultural practices and hence, the biggest representative of our popular culture. I wrote this article because I felt that we were overlooking our social contexts when we were essentially trash-talking our popular culture. I wondered if this dismissing attitude came about as a way of ignoring social responsibility; were we already aware of how we lived and didn’t want to confront it, when it manifested in pop culture?

by Adrija Ghosh | Calcutta, India

— —

Our popular culture is as reflective of our taste and cultural practices as our nation-state’s democracy. The democratic structure requires representatives, and pop culture requires icons. Undeniably, Justin Bieber is one of the most visible pop icons of, at least, my time. Our popular culture is replete with commercialisation, de-sensitisation and misrepresentation, and perhaps then the biggest hits that come out of it are so as well.

It’s easy to say that the media is spoon feeding us, but like Althusser had theorised there are a lot of apparatuses, otherwise, in function here. There is an anxiety for resources and how we can access them. It can be anything from cultural or capital, to economic. Think Zelda Fitzgerald giving the financial boost to Fitzgerald and his aspirations for inclusivity in the cultural circles of the ’20s – and what did he even write about? Debauchery, money, insecurities, infertile human relationships. His reality.

We haven’t been turned into bricks solely by external agencies. We have enough agency of our own to shrug off any form of social responsibility. This trial and error to achieve a more wholesome balance that is tolerant, self-critical instead of being self-indulgent can’t be achieved unless we realise that we are too damned complacent. We resist change. We are comfortable in claiming individual taste, and can’t criticise ourselves because that involves our time somewhere else other than pursuits of social, economic hierarchy. We are okay being rigid. We are okay when we are supposed to be questioning while retaining compassion.

So, maybe the “cultural paralysis” of recent times is reflective of how people would rather be ignorant and caught up in the bygone eras; to insult and dismiss contemporary popular culture at face value, but not confront why our recent pop culture is the way it is.

Your, mine, and our popular culture is reflective of what we are consuming as a society. There are more songs about money and hypersexualisation, because this is a money-obsessed society, steeped in capitalist interests that is mainly propagated through the ads you consume. It’s a form of self-fashioning. We can listen to the subversive, pop culture of the past decades, such as Morrison, Joplin, Presley, Hendrix, The Beatles, Hendrix and we are willing to analyse their cultural, socio-political contexts, and assume ‘class’ or refinement in taste because they’ve been declared as classic owing to time. When Cobain did what he did, how many people took him seriously? When Michael Jackson became an icon, why did people try to reduce his credibility as a performer?

The first vehement contestation would be, that he’s not a part of “your” popular culture because you don’t ‘listen’ to him. I wonder if a generation’s popular culture can be located in a time that it does not occupy.

Isn’t our popular culture a representation of what we, as a generation, are consuming? Our popular culture is fueled by narcissism, self-fashioning in the virtual reality. Haven’t we collectively forgotten about social responsibility? When we are preaching to be “woke,” “politically correct,” and “aware,” how much is it to educate our immediate peers and family, instead of maintaining a carefully curated image?

If you listen to a particular genre of music, why hasn’t your “taste” been an influence upon your immediate peers who are perhaps listening to something you degrade? “Taste” is a social construct. It is reflective of your “culture,” which is different for each class. Your “culture,” your “taste” become testaments to your accessibility – your privilege; your class-sanctioned normative. Your idea of the cool, of the awareness becomes a force of Othering.

I was in my seventh grade when I first encountered the pop phenomena that Justin Bieber would be. It was one of his covers on YouTube that I came across. Then he released his first album. Then “Baby” happened, then the following World Tours, the teenage angst, the arrest, the sabbatical followed. He came back with “Sorry” and the world grudgingly, perhaps drunkenly, danced to his tunes once again. People have always been dismissive about this 23-year-old Canadian singer. They don’t consider him to be talented. His music is relegated to the people who have “bad taste” in music. He has been consistently criticised, misgendered, ridiculed, undermined. He himself has consistently made a lot of mistakes that perhaps, are characteristic of his age. But, all this is rhetorical. As much as the world dislikes Justin Bieber, he is never invisible. People are always talking about him, passing judgement… you know what the story is. You never stop discussing him. He is, after all, a huge representation of our popular culture.

How does it reflect the society you are located in? Well, give a 14-year-old child, who is ambitious for social mobility and economic development, the amount of money, endorsement, attention you associate with pop-culture, and what happens? Justin Bieber becomes an example of what this money-driven, American dream-chasing society can be. You socialize a kid into the context where he becomes a machine that perpetuates wealth, take away the normalcy of a teenager, and you get a troubled child. Bieber sings about money and women, he exoticises, he shows off, because that is what we as a society are doing: Objectifying women, appropriating others when necessary to our convenience, and chasing the good old paper. Success has become about how much popularity one has, and how it is reflected through the commodities you use. Think Marx and his idea of commodity fetishism.

We created a Justin Bieber. He became the first popstar of the social media generation. Don’t deny your popular culture, because then you’re perpetuating the ideas you so ideally oppose. You turn a blind eye to your popular culture and it gives you byproducts that you can’t claim, because you never had the courage to fix the flaws, to accept the course it’s taking.

So, what could Justin Bieber do? He took this harsh judgement and decided to dismiss the world as it dismisses it, and continued what he wanted to. He doesn’t have to be responsible for an audience that refuses to see how ideologically flawed it is; he can just make money. But he is still doing positive things, bringing about positive changes. He’s doing his part. You, perhaps, are doing yours. All of us have let Capitalism trick us into believing in the invisible hand. Well, Adam Smith was wrong. Unless we look beyond ourselves and our individual contributions, bubbles, we cannot improve ourselves as a community or as a culture.

It is our popular culture. If we want something more from it, we need to make it more accommodating of all kinds of narratives and languages, the unheard and oppressed more than others. Maybe we wouldn’t hate Justin Bieber so much if we could see that he’s singing about his reality, which is money obsessed, superficial and shallow. Maybe that’s why he, too is inclining towards spirituality to understand his context better.

Analyse your ideology, see what kind of life you live and what kind of life you want – what are you running towards? – and then see if it has resonance with your popular culture. If it does, then the fault is not without, but within.

Popular Culture exists because of Capitalism. You follow the contemporary trends, and it becomes a part of your consumption and your social context. One singer isn’t the representative of the entire popular culture, but all of our perspectives, lifestyle, and desires, are.

— —

:: about Adrija Ghosh ::

I am from Calcutta, India. from Calcutta, India. I am currently pursuing English Honours at LSR, Delhi University. I am an enthusiast of indie rock, and the 60’s-70’s. I have been heavily influenced by the Lost Generation and the Beats.

— — — —

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

You May Also Like….

Understanding the Importance of Father John Misty's 'Pure Comedy'

by Mitch MoskSuccess and Sacrifice: Cold War Kids Discuss 'LA Divine'

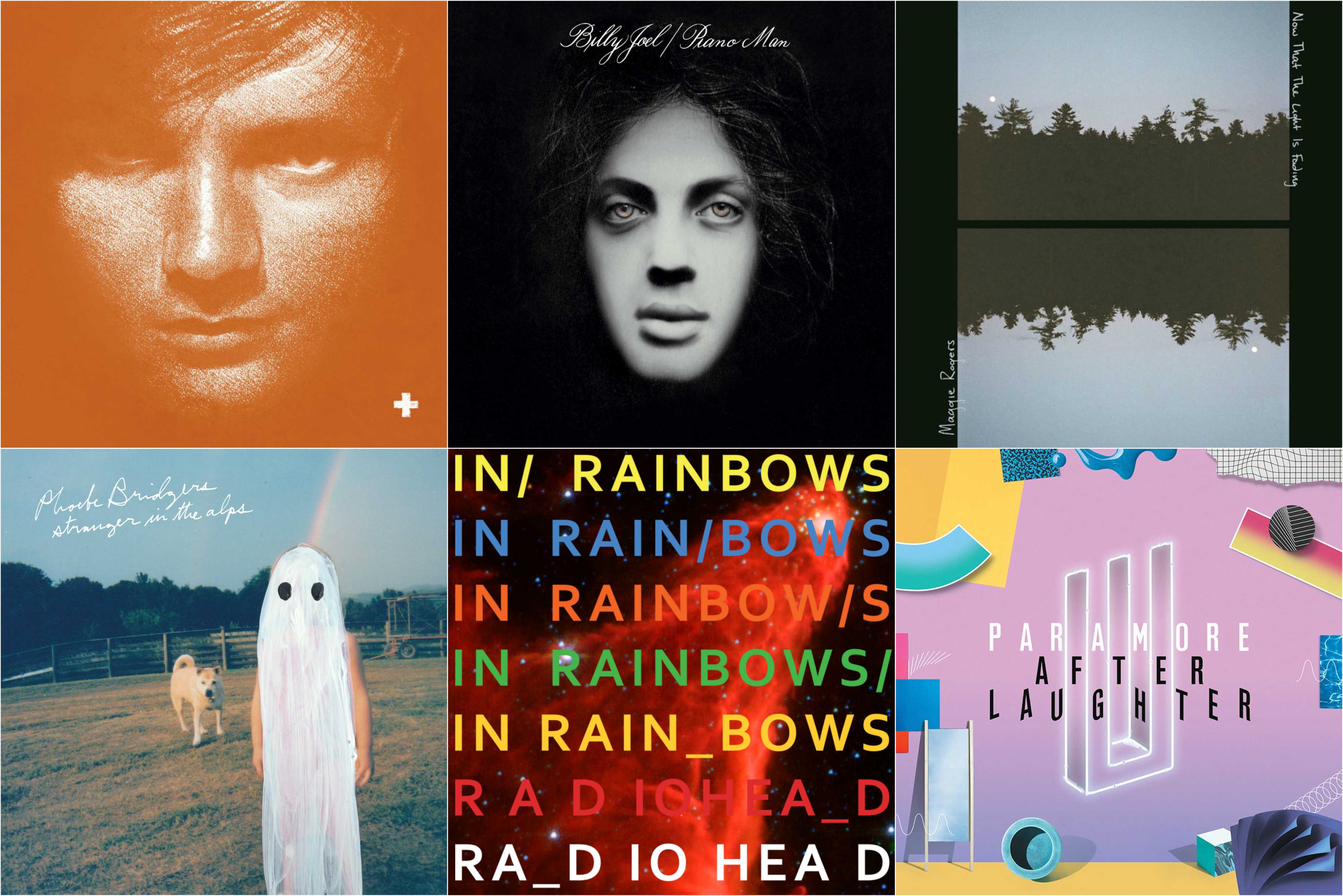

Our Favorite Albums of the Decade: 2012

You may also like

Premiere: A Deeper Love in Forest Blakk’s Moving “Where I First Found You”

BETWEEN FRIENDS Prioritize Thinking Less & Enjoying More, Generating Their Most Authentic Music to Date

Video Premiere: Greyface Get Along on the Feel-Good Warmth of “Delilah”

Fruit Bats’ ‘A River Running to Your Heart’: A Journey of Geographical Emotion

Album Premiere: Gizmo Varillas Shines a Light in ‘Dreaming of Better Days’

Atwood Magazine’s Thanksgiving 2017 Albums