Atwood Magazine reconnected with Jacob Allen, the singer/songwriter, producer, and poet also known as Puma Blue, to talk about his deep love of music, how his connection to his friends altered his approach to making records, and what darkness means to him.

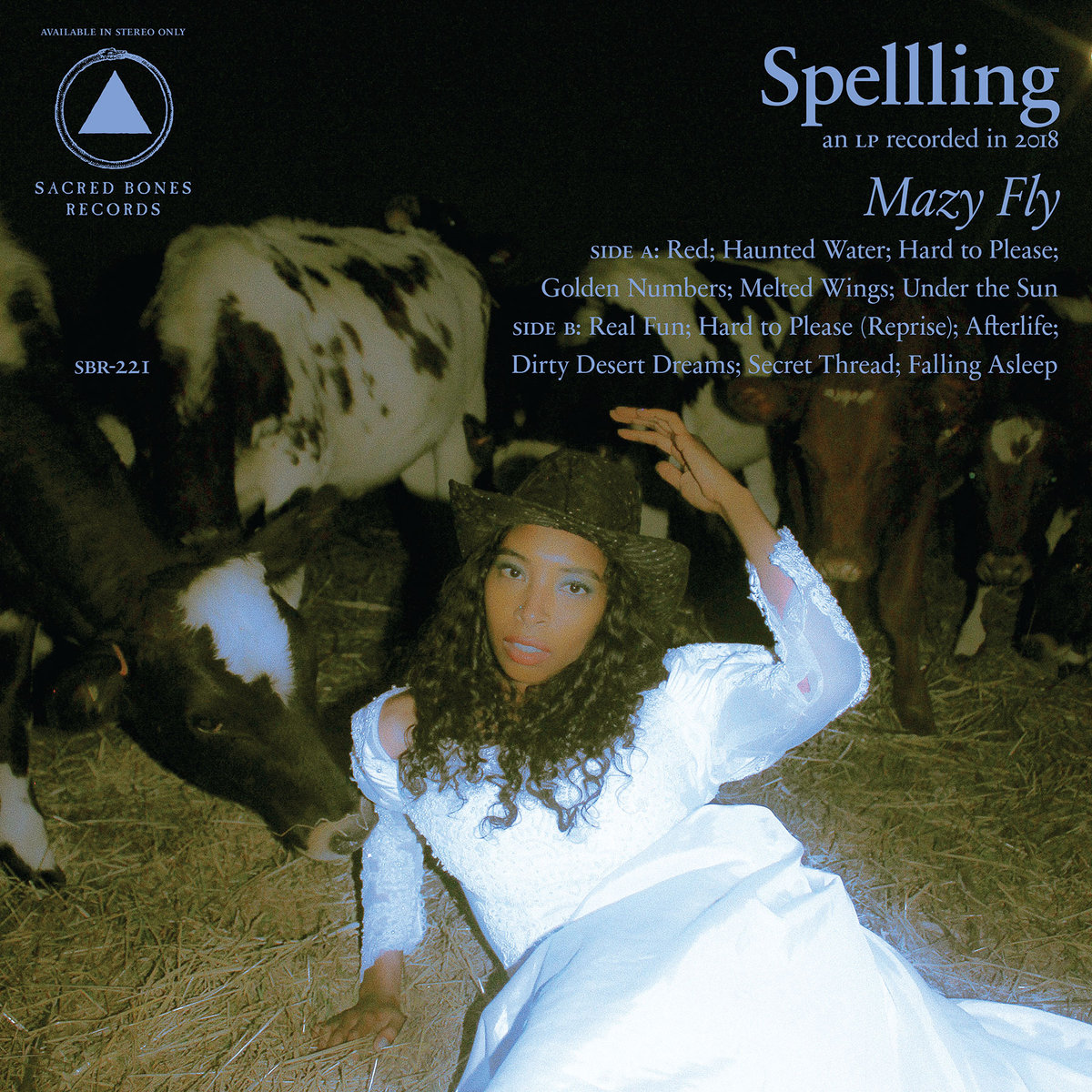

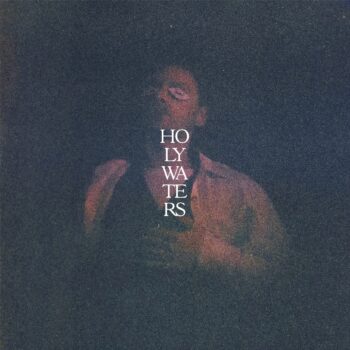

Stream: ‘Holy Waters’ – Puma Blue

Holy Waters, the newest album from Puma Blue, was born from exploring the realms of elation and grief, life and death.

Ever familiar with exploring shadows, in the time since releasing his first album, In Praise of Shadows, Jacob Allen, the creative force behind Puma Blue, has learned to appreciate the light just as much as the dark. Crediting his friends and bandmates as well as his partner as being the most important things in his life, it took the isolation of quarantine for him to put that feeling into perspective. During that time his appreciation for the music they’ve made together only grew stronger, which ultimately led him to shift how he approached his artistry. In the studio for his second album, Jacob Allen aspired to capture the alchemy of energy and charisma made when he and his band would riff off one another. The resulting album was inspired by and infused with the chemistry of their friendship.

In an effort to make a more collaborative record, the members that make up Puma Blue (now seen in Allen’s eyes as a band instead of a solo project) decided to make a band-led live album. The music made in the process of experimenting with their sound is a marriage of Puma Blue’s previous laptop-produced nocturnal music to the improvisation-heavy live performances the band has become known for over the years. Straying from his earlier approaches, Allen relied more on his band of friends to help make decisions while recording. No longer bringing near-finished demos to his band for them to record; now whole songs were given life in the studio from start to finish. Thus a new era of Puma Blue was born.

With growth came a deeper understanding of the world around him. For Jacob Allen, that meant a deeper exploration into the darkness he has always been so comfortable in. But recently having to come to terms with death gave Allen a whole new idea of what light and darkness could be. Holy Waters is the perfect example of that growth, with Allen even saying, “Sadness and darkness are necessary things; they don’t have to be so dooming.”

While his message remains the same – “that there can’t be light without dark” – Allen’s approach to conveying it to listeners has shifted, equally embracing the light and the dark. Holy Waters is an album that is as appropriate to be blasted with the windows down as it is to be played in the quiet of the night. Its duality in theme and tone only mean it never ceases from lingering in your mind.

Atwood Magazine reconnected with Jacob Allen to talk about his deep love of music, how his connection to his friends altered his approach to making records, what darkness means to him, and his new album, Holy Waters, released September 1st, 2023 via Blue Flowers.

— —

:: stream/purchase Holy Waters here ::

:: connect with Puma Blue here ::

A CONVERSATION WITH PUMA BLUE

Atwood Magazine: You mentioned before that the album cover is a reference to Cocteau’s The Testament of Orpheus, would you mind talking about the inspiration behind that?

Jacob Allen: Sure, this is a film that my partner put me on to during the pandemic. I guess what struck me was it was somewhat of a death scene for Cocteau himself, and these eyes are sort of representing the coins on the eyes that they used to do at funerals. When it came to deciding what this album should look like after much of it was recorded, the main thing that tied everything together was this sort of theme of death and that being both celebrated in some ways, like there are moments where I feel like I am coming to a place of accepting it and even making light of it, and then there are other moments that feel very painful. And this album cover, this reference as well, it felt like acceptance, it felt like a visual way of explaining – or just showing – that this wasn’t such a gloomy message.

Originally, I was looking at something a bit more like the cover of the Black Sabbath album, the original one [Paranoid], something that would say ‘Death’ instantly, that you would just get it without me having to explain. But the more I went down that path visually, the more I realized that was the wrong mood, it wasn’t the right color. So in the end, I went with something really colorful. And I felt the eyes: it was like capturing this moment of almost enlightenment, a sort of in the face of death just kind of feeling at one with it and just accepting it, and that being kind of this colorful moment, rather than such a moment of doom.

Speaking of color, I feel like your music is very colorful. Maybe because it’s literally in the name: ‘Puma Blue.’ But someone asked you this in a previous interview, so I thought I would do it again. What would you say is the color palette of this album?

Jacob Allen: Ooh interesting question, (pauses) I definitely feel like there’s a dark orange. I feel like orange is this very creative color, and this is my most collaborative album to date; I’ve really involved a band this time, which is something I’ve not really done before. They’ve played on a couple tunes here and there, but it’s usually just me alone with a laptop. And this time, it was like a melting pot of all our influences, we were just so close and intimate during the making of this album and really there were no wrong ideas. I feel like our time in the studio felt very orange, very kind of bubbly, dusky sky orange. But there’s maybe a pale blue or grey as well. There’s a tinge of sadness that runs through the record. I feel like sadness is even the wrong word; it’s not like melancholy or misery, it’s just like a cathartic sigh and I feel like that’s a very blue/blue-grey color. We recorded it in Eastbourne in England, which is a very blue-grey place as well. (laughs) Sort of the sea is always silver-looking.

So it’s kind of reflecting that area?

Jacob Allen: Yeah totally, but then all the liner notes and the videos, they’re all in black and white because I wanted it to be this kind of classic thing going on, so yeah there’s a little bit of that noir palette as well.

You talked about how you involved a live band a lot more this time. What brought you to do that, to make this big shift in creating music?

Jacob Allen: Well, we’ve always been really good friends, we’ve always been really close. We did this tour right before the pandemic, in the US. It was like November 2019 and it was just some of the best weeks of my life honestly. There was something happening in one of the band member’s personal lives that was very tragic, so I think in a strange way, although the timing of this tour was kind of awful, it was a very special time to us, as friends. We were just really sharing that grief together and going through it together. I think being able to play music every single night while a member of the band is grieving, it felt – I don’t know, you can’t really plan for that — it just felt really special. And I came off that tour feeling like the band was, maybe aside from my partner, the sort of best thing in my life; the most amazing vessel and vehicle for energy and magic and alchemy. Then we had that whole year following it where I couldn’t see them or play with them. So naturally when it came to working on album two, I felt like I had come around to thinking the most special thing about Puma Blue was us as a four-piece rather than anything I could do on my own. It just was really important to me to accentuate the size of the music as much as I could. The things that they’ll just do naturally — because I encourage a lot of improvisation on stage — the sort of organic moments that just happen, you can’t plan those when it’s just you and playing all the instruments and doing it alone on a laptop. I just really wanted to capture some of those moments we had live on a record. I hope that will come across when people listen; that it’s just a bit more about the chemistry between us. I just missed them a lot during the pandemic, and I’d also been meditating a lot before on the idea of doing something a bit more band-led. I think because I couldn’t for so long it just sort of felt like it had to happen on this next one.

I feel like “Hounds” really shows that, it feels very much like a full band kind of song, if that makes sense.

Jacob Allen: Thank you, that was the first one I wrote for the album. And I really just brought it to them as this very rough demo. So it was kind of the first time that I heard the idea of doing a band record, it was the first time that I felt that kind of come true. It was taking them this demo that sounded very much like my early stuff and then working it out together, like “how can we change this from a demo into an album recording?” Once that song was done, it was just like “okay, this experiment is gonna work.” It was the song that helped flip the coin.

Yeah, was that part of the reason for it being the first single?

Jacob Allen: Yeah it was. I just wanted to show people what, in my mind, was the most immediate version of the album, and that had to be like this sort of first thing we did. When I was working on the mix with Sam Petts-Davies, who mixed the record, we had this phrase that we would sometimes come back to. It wasn’t always appropriate, but this idea of “first thought, best thought” and sometimes your gut is right, you know? You can think about it and over-intellectualize it, but sometimes you have to kind of go with the thing that you saw first, like your gut instinct. I think “Hounds” was one of those. I wasn’t even sure if it was a song that would work under my umbrella of music. Or how it would work translating it with the band. Or whether it made sense as the first single since it was kind of long and – I hate this word – but like ‘rocky,’ I guess ‘heavy’ is a better word. But yeah, I just felt like as soon as I had that gut thought of “oh it should be Hounds,” I could think about it all I wanted, but that was obviously the gut instinct, so that’s why we kind of went along with that one.

That makes sense, “Hounds” was just kind of the first everything! (laughs) The first Holy Waters – “Hounds.”

Jacob Allen: Yeah the first of everything, exactly.

I saw on your artist bio that you guys had another saying of “every element should sound like the loudest element.” If you wanted to talk about that too? I think that’s kind of an interesting approach, and I feel like it applies to “Hounds” too.

Jacob Allen: (laughs) Yes, thank you! That was the first time we tried that method, so that’s funny. It really was the first for everything. I had help on the second EP [Blood Loss], but I mixed the first EP [Swum Baby] myself, and then Marta Salogni mixed the last album, and I was very proud of them at the time. But I think coming away from those three records I felt like something I could see, now that I had some distance, was something I’d treasured before being subtly and being delicate. I had gone too far and actually there were a lot of layers and attention to detail that I felt got lost in the mixes because I was being so subtle. It was too subtle. Now, I listen back and it’s like I can’t really hear all that stuff that I spent time working on, it’s kind of lost in the fog a little bit.

So when it came to this record, I just wanted to kind of slap people in the face with it a little bit, and just be really bold. I’d been listening to music that was doing that a little bit more, and when I was listening I was thinking, “God, all these paint strokes are very bold and striking, and even if something is subtle it’s making itself known. It’s not whispering, it’s just there in the distance, but clearly.” I didn’t want to make another record and get the band involved and go through all this effort of making something we really cared about only for it to kind of get lost a little bit in the whispery, faint version of how I would usually decide to mix a record. So yeah, when I was working with Sam on the mixes, we just had this idea of, “If something is there that can’t really be heard, then we should just scrap it completely. It’s clearly not important, and if it is important, then we should make sure it’s heard. And everything should almost be — not fighting to be heard — but everything should exist in equal importance.”

I didn’t want to make a record that was overly compressed and squashed and all the sounds were fighting each other, but I wanted to make sure that if something was going to happen it would take main stage. It would be front and center, and you would notice it because I think a lot of my stuff before has so much detail that no one probably hears because it’s so buried in the mix. So yeah, that was important to me. I think we applied that even in the compositions: like if there was going to be a part then we were like “let’s make that important” rather than it just being kind of a little side moment. Does that make sense?

Yeah that totally makes sense. I feel like even the songs that start quiet and soft, build up to the end. There’s always a big flourish at the end. So that kind of plays into the ‘loud element’ too, even if it’s soft, it will get loud later on.

Jacob Allen: Yeah, I’ve made a lot of stuff in the past that I could see – and to be fair I haven’t heard that criticism but I’m just sure it’s out there and we’re our own biggest critics anyway and that’s what’s important for growth – but I could see my older stuff being construed as hushed. I think fragility is amazing but the idea of it being weak or frail, that bothers me because fragility is actually really bold. But frailty: that’s the wrong impression. So I wanted even the gentle songs to feel like if they were going to be fragile then they had to be bold with it because there is a difference. I think with songs like “Epitaph” and “Light is Gone” I needed to make sure they felt important, otherwise they would just not make the record. There was no point on this album. I’ve done so much frail stuff over the years it was just like nothing can be that way otherwise I just don’t think it should be released. It was important to me that everything has an importance on the record.

Speaking of ‘fragile’ kind of, “Pretty,” the song you released recently is like that. It’s fragile but not in a frail way, in a way that’s stronger. It’s very raw.

Jacob Allen: Thank you, yeah it came from a raw place. It was one of those songs where as you were writing it you were sort of like “well this is just the first draft. It can’t be this obviously, I’ll have to change it because it’s too raw.” But then the more you fuss and edit the lyrics, like the more I was sitting with it the more I realized again it couldn’t be anything but the first thought. And I had spent time on the lyrics in a craft-like way to make sure they were right in terms of the poetry of them. But also in terms of the message and especially the chorus: there were like a million ideas I had to change it to be something less – to put me less on the fucking guillotine – but then I just thought “what would be the point?” And surely the music that we connect to the most is at its rawest form when we understand what the artist is saying to us because we sort of feel it too. I just thought I hadn’t heard anyone say that before, so I wanted to say it because it felt true, and it felt like you said, it felt raw. I was worried about putting myself out there that much, but now that it’s out there I feel like that’s really silly and I’m glad that I just did it.

And you said, in reference to “Pretty,” that you saw it as a sister song to “Want Me,” correct? Do you want to talk about that?

Jacob Allen: Yeah of course. It wasn’t something that I immediately felt when I was writing on it, but it just happened very quickly as we were working on the song. First of all, I’d written the guitar part like two or three years after I’d written “Want Me” so in my mind it’s from the same time in a way, just the instrumental side of it. So I was in the same harmonic mindset when I wrote both songs. I was listening to a lot of jazz back then and I can hear that in the music; when we were working on it, we were going for something more classic sounding. But more so I think why I said that was because both songs come from a place of rejection and feeling small. “Want Me” was a song about confessing feelings for someone literally on a dance floor and not hearing the response you were hoping for and then kind of going home and sitting with that feeling and feeling like “shit I thought I really had a chance but now I realize that I never did.”

Whereas “Pretty” is almost the flip side: Where it’s like you’re already coming to the party with this feeling of insecurity and smallness and feeling ugly – and unworthy is the word I’d use. But I think what’s really beautiful about this song compared to “Want Me,” all these years later, finding the lyrics now, is that the answer is you are beautiful, and I do love you. It’s a song about someone making you feel beautiful in spite of your insecurities. Whereas “Want Me” is the other way around, it’s like you arrive feeling like “surely this person wants me” and then they say they don’t and you have to work that out. But this song, I’d like to think I’m narratively coming away from it feeling better, even though the last line is “you make me feel so pretty and I’m not pretty at all,” I still feel like that’s the beautiful message behind it. It’s like I could be ugly, but it doesn’t really matter when you’ve got this person that loves you in your life, that thinks you’re beautiful because it’s their perspective that matters at the end of the day.

Yeah that’s really pretty.

Jacob Allen: (laughs) Pun intended? That was really smooth.

(laughs) Oh no I wasn’t actually trying to make a joke, but we can pretend like I did. But speaking of the songwriting a bit, we talked before about how this album was more collaborative with your band. Did that approach affect the songwriting as well, like with the lyrics or anything?

Jacob Allen: Yeah a little bit. It was interesting, there were some songs that we wrote completely together, like “Too Much, Too Much” and “Gates (Wait For Me).” And “Epitaph” I wrote with one person in the band. Those songs came out of jams. We sat down before there was even an idea of what we should do for the day and we would start playing; those songs were born from the jams we were having. And then I would go away and write the lyrics separately. But there are a couple of cases, like “Falling Down,” I had help with the lyrics from my friend Luke Bower, who is like an unofficial member of the band, he used to play guitar with us, but we don’t really have the extra guitar anymore. He was there when we were working on the album in the studio, and he played guitar on some of the songs and stuff, and we were all tracking it live. But then some songs like “Pretty” and “Hounds” which I mentioned already, “Mirage” even, “Holy Waters,” I had written the song and recorded a demo, and I brought it to the boys almost saying “this is finished, right? Let’s learn this and play it.” But then through the process, these songs would become completely different. “Mirage” for example, I was gonna leave it off the album. I felt like the lyrics were important to me — and they still are — and they felt like they occupied the right space in terms of what the album was about, but I didn’t like my demo, it was too grungy or something. I remember thinking, “I don’t really need this song.” But we had this idea to sort of turn the first half of it into a lullaby, which went with the song lyrics. Only through that process of working on it with the band, did I love and approve the song. It was like, once everyone figured out how we were going to make it sound, suddenly the song I had already written became something else.

So yeah, there were times where it was a bit more straightforward, like “Holy Waters” and “Oh, the Blood.” I just kind of produced those and wrote them on my own. But songs like “Mirage” and “Hounds,” they wouldn’t sound the way they do unless the band had affected the writing process. And then some songs like “Too Much, Too Much” and “Gates (Wait For Me)” wouldn’t even exist if we hadn’t written them in the room together from these kinds of improvised jams. There’s a whole mix across the whole album honestly, but the cool thing was even on the songs that I was working on alone, like “Oh, the Blood” and “Holy Waters,” I felt like the band still had a say because they were invested this time and they loved being part of the process. Everyone had an opinion which meant that it wasn’t only me making the creative decisions. So I feel like the filter as to what was good art was better because there were more people than me deciding. They steered me right.

Yeah right, it was more filtered I guess. Again talking about collaborations, I heard that you have also been helping co-write and produce with other artists. What was that like? What brought you to do that?

Jacob Allen: I’ve honestly always done that. It’s something I’m very passionate about because I love this world that I’m a part of, this Puma Blue project that I reflect — I wouldn’t say created — it’s something that I am participating in. But it’s just that I listen to so much outside of the sounds that I am making, so I don’t think I would feel musically fulfilled if I was only working on this music. I’ve always loved the chance to explore other people’s worlds and I like them taking me to their musical space and being able to explore that with them and hopefully bring something to their world that they didn’t have before. So it’s something I’ve done since music school when I was 16. These days it’s fun to work with people that really know what they’re doing, not in terms of their ability but more in terms of their vision. It’s fun to work with people that know who they are and have something to say, and you can kind of just show up and bring a little of what you do but also try and kind of meet them in their world. So it’s really fun being just a producer or just a guitarist, as opposed to a singer or the artistic voice. It gives me a lot more freedom to do stuff that I wouldn’t do in this project, and hopefully kind of just accentuate what they’re doing already. Yeah, I really love it. I’d love to do more, especially in the hip hop and R&B realm. I feel like that’s where my production lends itself better than say guitar music, which is kind of what I’m doing in this project, and maybe that’s why I don’t feel the need to do that so much. But yeah, when I’m home alone I’m mostly just listening to like Burial. So I love to make productions for people and to work on songs for other people and just explore their sound with them.

Yeah that’s really cool. And you had a radio show right? Like during this past fall was it?

Jacob Allen: Yeah I used to. I really miss it actually. You can put it in the article: if anyone wants to hire me. I was working with Worldwide FM based out of England, and that was a monthly show and just so fun to share music and to just sort of explore with the listeners the stuff that I find in my headphones every month. But unfortunately they had to stop their radio station, they kind of hit a bit of a financial wall. I think they’re still going in some capacity, but they had to let go of everyone. So yeah I really miss that, it’s really fun. I love to curate playlists and DJ. Sorry, what was the question?

It just came to me when you were talking about the other artists. There wasn’t really a question. Just hearing you talk about loving to share music with other artists reminded me of your radio show.

Jacob Allen: Yeah it’s great, I just love to put people on to good stuff just as much as I love to get put onto good stuff. I think there can be a little bit of a gatekeep-y thing when it comes to some of the DJ culture and some of the radio culture. I love when stations cater towards letting everyone in, like “come sit with us,” as opposed to “you can’t sit with us.” That felt like a really fun opportunity to explore that and put people in front of the music that inspires me.

It’s true, people do tend to gatekeep music! I think it happens in every genre too.

Jacob Allen: Yeah I agree, I don’t know why that is. I guess because music feels special and maybe some people feel like they’ve put in a lot of work into finding cool stuff, but I just don’t know why it has to be like that. I think if you’ve got something good you should share it. It’s too much of a sad world to gatekeep things.

With your debut album In Praise of Shadows, you talked about the title being a celebration of darkness in a way. But then with this one, Holy Waters, it ends with the message of “don’t let the dark take you whole.” Would you say your relationship with darkness has changed?

Jacob Allen: It’s just deepened. I don’t know if it’s changed. I still feel like in a way, this album is the same message: that there can’t be light without dark. I feel like in a strange way, that’s been my message this whole time, since the first EP, I just didn’t know that at the time. I think In Praise of Shadows was the first time I managed to articulate that, and with this album it’s just deepened. I just feel like the lights are brighter, there are some moments on this album that were genuinely some of my favorite moments I’ve experienced in music, like we were just all playing together and so present with each other and I hear that back and I can’t believe we managed to record it.

It just feels like a beautiful photograph of a moment that you’re so happy you’ve managed to photograph. But then the darks have so much more depth to them now. And I’m not just singing about heartbreak, I’m singing about death. Life just got more fucking intense since the last album. (sighs) Oh it’s just a lot more of a grown up feeling, you just get to this age and suddenly shit is a lot more real. I feel like that last line was my way of saying “don’t let it win.” After the first album, it was so important to me that people take away the message of: sure this can be your sad music if you want it to be, but only if you’re taking it away with this message of that that’s important as well as the other side of it. Sadness and darkness are necessary things; they don’t have to be so dooming.

So I guess for this album and the subject matter, I wanted to make sure I didn’t leave people with the wrong message that there is only darkness. I think that it was important to just have a footnote at the end of the record that just said, “these can be scary things to look into, scary tunnels to go down, but you can’t let it swallow you at the end of the day.”

Very well put. Is that what you’re hoping listeners will get out of all of it?

Jacob Allen: I don’t know, I think with this album I feel less pointed about what I want people to get from it. I think with the first EPs, I just really wanted people to get me generally; I just wanted people to understand the sound and the colors of the music and that shit. And then with the first album, it was like I really wanted people to understand what I was saying. And now on this record, I just don’t care. I feel like I’ve tried to paint it in this way that hopefully people should be able to take whatever they want from it and that would still be roughly within the parameters of what I was trying to express. It’s both less open to interpretation and hopefully more as well. I’m being more specific, these songs are about a lot more personal things, but I’ve tried to write it in a way that you could listen to and relate to a bit more openly. I hope what people feel is just catharsis for listening to it, like for any music honestly.

I just hope that when people are in the mood for this record, it’s the one that they think of and put on. But I don’t really mind how it makes people feel or what they take from it. Even to me it’s a record about death, but maybe to other people it won’t be, apart from maybe two songs that really particularly are. So yeah I don’t really mind. I hope people think that it’s a more mature record, that’s the only thing I’d like from this experience. I’d be really sad if people were like “this is a really immature album from Puma Blue.” (laughs) Other than that, I don’t really mind.

— —

:: stream/purchase Holy Waters here ::

:: connect with Puma Blue here ::

— — — —

Connect to Puma Blue on

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Olivia Han

:: Stream Puma Blue ::

© Olivia Han

© Olivia Han