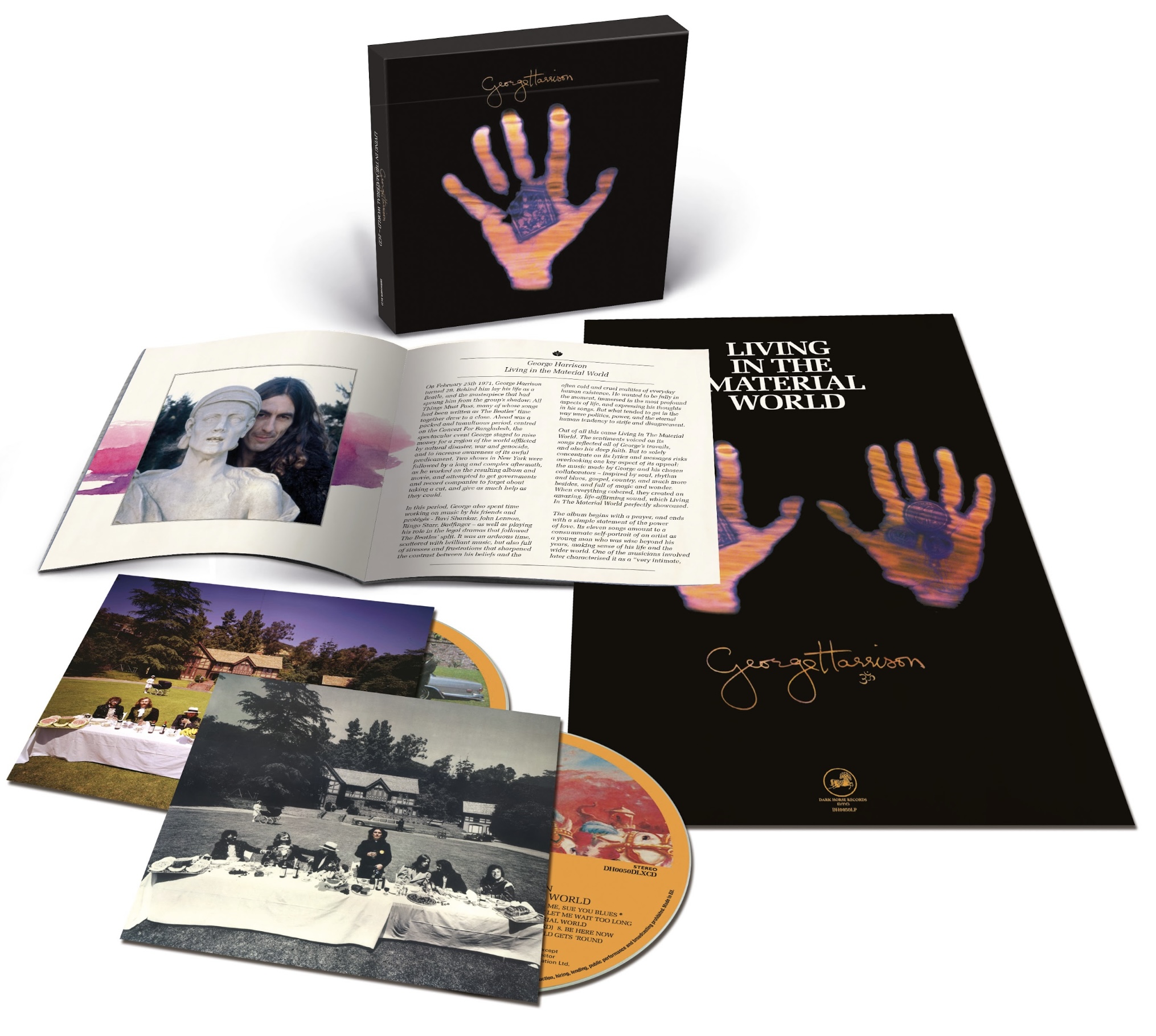

In a long-awaited follow-up to 2021’s Grammy-winning ‘All Things Must Pass’ box set, Paul Hicks revisits George Harrison’s ‘Living in the Material World’ with a remastered collection overseen by Olivia and Dhani Harrison.

Stream: “Be Here Now” – George Harrison

At the turn of the millennium, George Harrison donned a familiar jacket, hat, and gardening boots and ambled across the gardens of Friar Park.

Pulling up a stool, he assumed the same spot on the grass as he had 30 years prior, flanked by three mischievous gnomes. This photoshoot commemorated the “Pearl” anniversary of All Things Must Pass, the behemoth debut post-Beatles triple album from Harrison. A sprawling, career-defining collection of indelible songs, as of this writing it has crossed the threshold of one billion Spotify streams. Harrison’s intention was for this 2000 edition to be the first in a series of remasters overseen by himself. Instead, a year later he was gone.

The entire Harrison catalog was remastered for streaming in 2014 and, most recently, adapted for Sony’s Dolby Atmos system. In 2021, George’s son and Grammy-winning musician Dhani Harrison revisited All Things Must Pass with frequent collaborator Paul Hicks. The result was a box set featuring reams of demos, alternate session takes and material that didn’t make the track-list that was shelved for future installments. Living in the Material World is a more intimate record, and the new box set reflects this framing; in addition to the remixes, each of the eleven album tracks gets one alternate airing, plus two B-sides and a genuine oddity that ended up on ‘Ringo’ (by Ringo).

Some may prefer the approach of the Dylan archive team- essentially unedited session tapes that span countless hours – or the Lennon archive team’s Evolution Mixes that chart the songwriting metamorphosis of an entire record. In this instance, the ‘less-is-more’ approach serves the material. These songs are carefully-hewn gems and each outtake is a rare glimpse into Harrison’s process. It’s impossible not to smile when George counts off the title track with “A-one, two, buckle-my-shoe!”

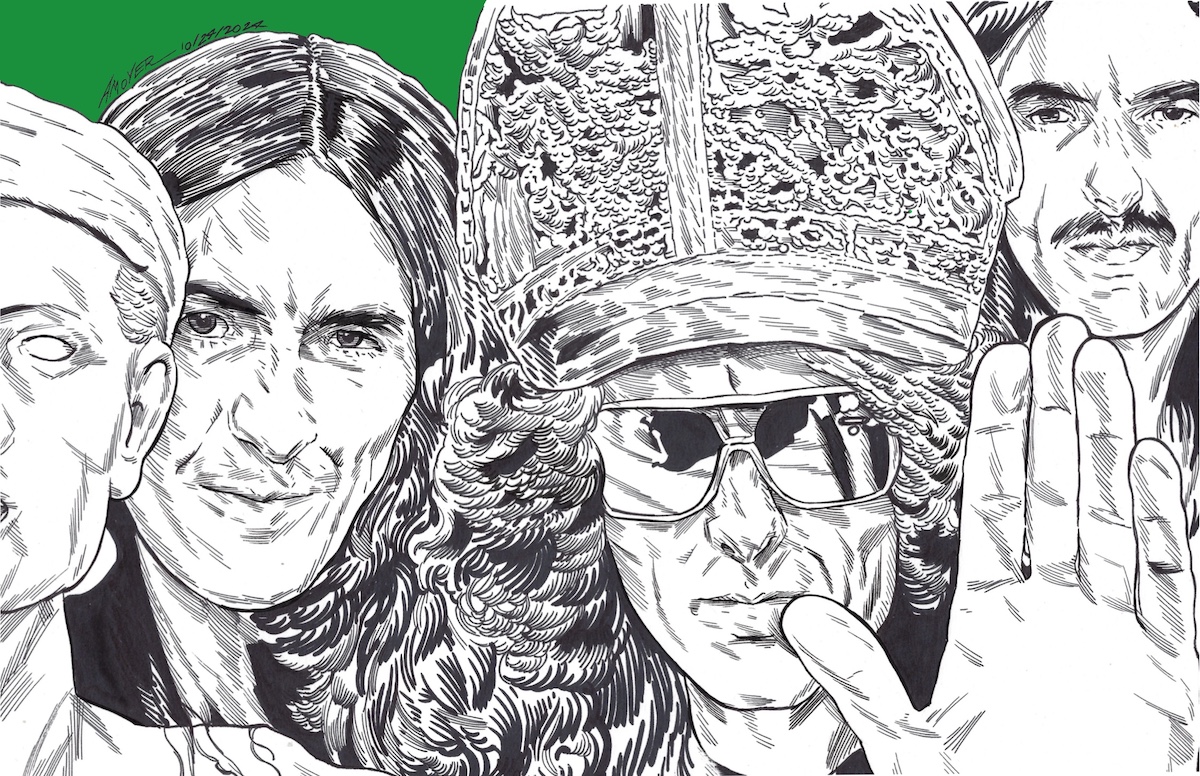

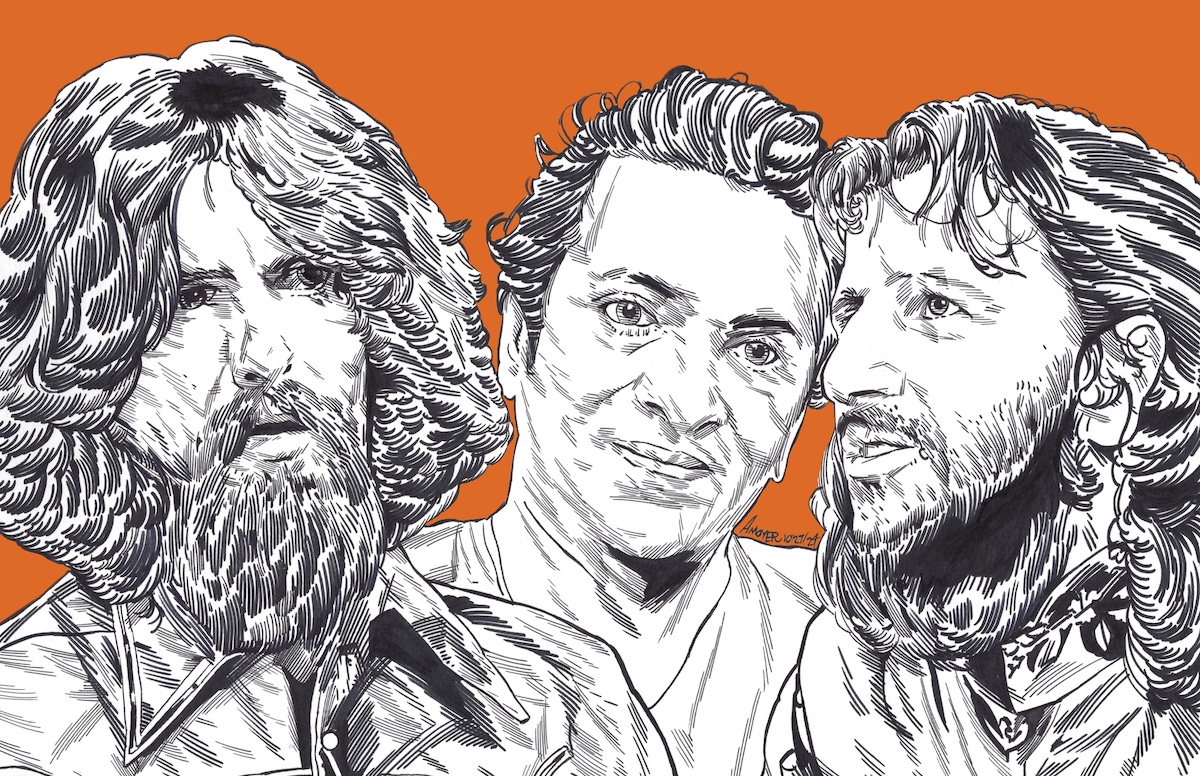

‘Material World’ came in the wake of the Concert for Bangladesh, the forebearer of all-star charity gigs like Live Aid and Amnesty International. Organized by Harrison as a personal favor to his friend and mentor, legendary sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, the effort sought to raise money for ailing refugees in Bangladesh. A lineup of rock titans including Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, and Leon Russell convened at Madison Square Garden for two shows on August 1st, 1971.

The subsequent film and double album was conceived as a purely charitable effort, through UNICEF; record executive profiteers and Allen Klein’s ABCKO stalled the cash flow. Fed up of waiting, Harrison established the Material World foundation and filled the coffer with the sustained proceeds of his next record – including this latest iteration.

The first record partly recorded at home in FPSHOT – Friar Park Studios Henley-on-Thames, Material World was initially supervised at Apple Studios by Phil Spector, in the loosest sense. After deciding that “eighteen brandy alexanders” to coax Spector into barely participating in the sessions was a liability, George helmed the remaining sessions with a lean, mean lineup: Bangladesh holdovers Jim Keltner and Klaus Voorman, keyboardists Gary Wright and Nicky Hopkins, the aptly named Jim Horn and Ringo tabla player.

This ‘skeleton crew’ worked through the fall of 1972 on a tight collection of intimate spiritual tunes. While ATMP is undeniable in its scope and replete with classic tunes, ‘Material World’ is “all killer, no filler.” Each track is meticulously arranged, replete with time signature shifts, flips into falsetto vocals and traces of the Indian music innate to Harrison’s spiritual practice. The album artwork and the new deluxe booklet underscores another intrinsic facet of George’s work: a Scouser’s sense of humor.

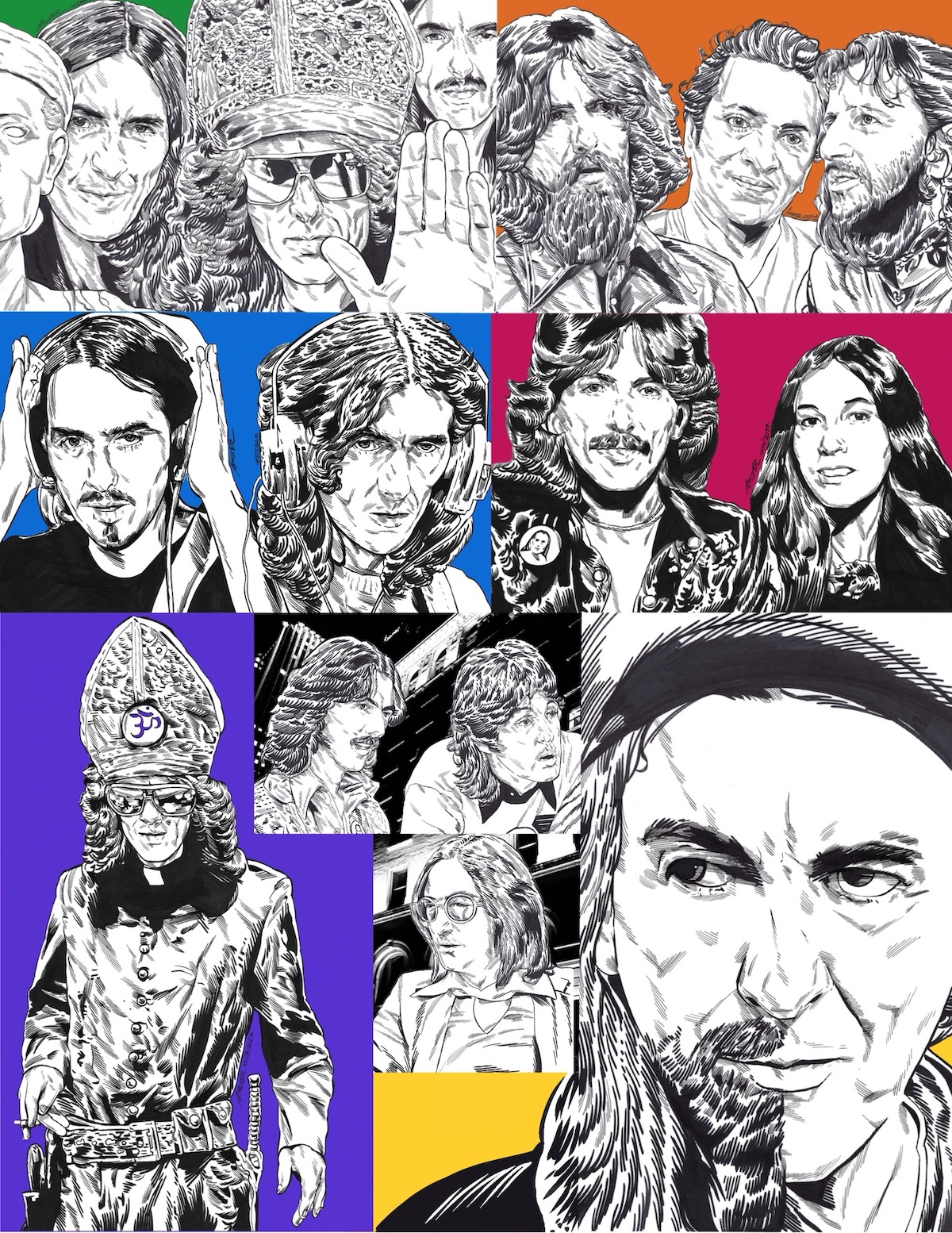

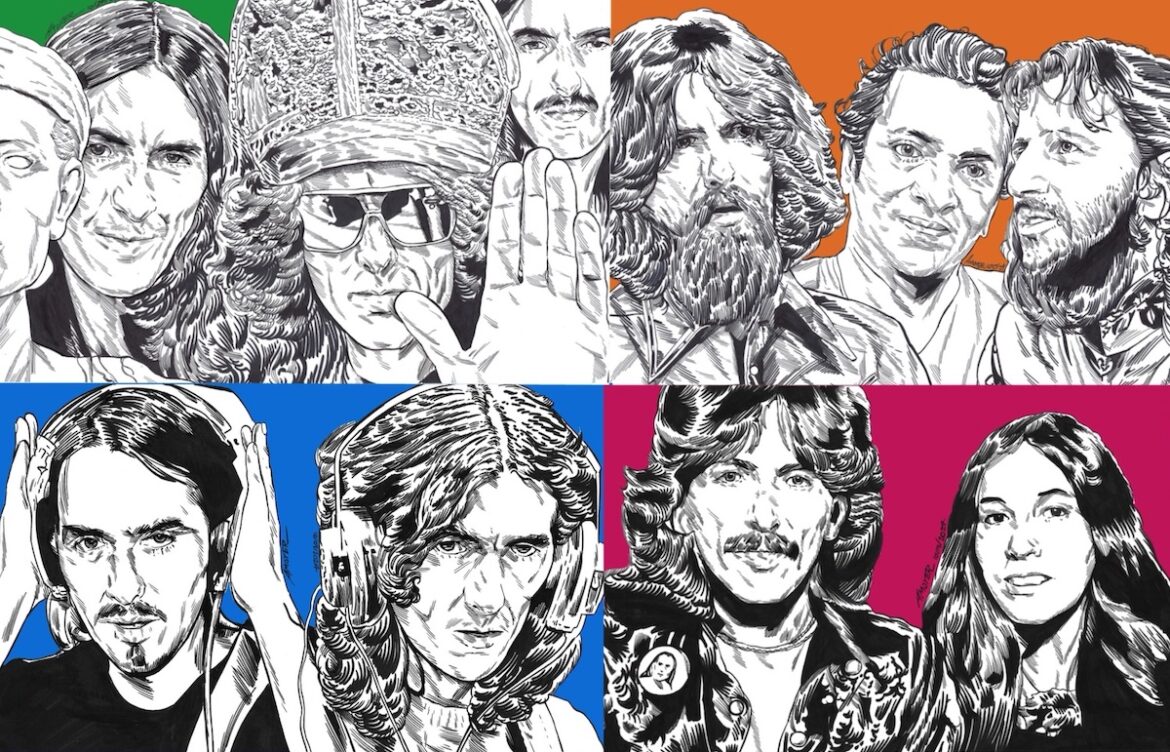

Harrison’s palm stretches over the front of the LP in an orange-purple tinged Kirlian photograph. He clutches a Hindu medallion, and the deities Krishna and Arjuna feature on the LP sleeve. The gatefold tells a different story. A decadent Python-esque spread of debauchery adorns a parody of The Last Supper staged at Friar Park. George, center, is clad as a cleric, flanked by the session musicians. A baby pram, an empty wheelchair and sleek sports car line the dirt path to the main house, where a promiscuous leg dangles from the window. In outtakes Harrison is wearing a Bishop’s hat, shades, a policeman’s belt and holstered club. The push-pull of the spiritual world and the perks of fame is on full display, and there are hints of discord in Harrison’s personal life.

Smudges, tears, and tape marks are among the archival artifacts of the scanned original handwritten lyrics throughout the deluxe book. Laid on end, the pages mimic the “Last Supper” spread, with prayer beads and strawberries adorning the corners. An intriguing alternate tracklist includes ‘So Sad’, one of the best tracks on 1974’s ‘Dark Horse’, ‘Beautiful Girl’ and ‘Woman Don’t You Cry For Me’ (both eventually on 33 1/3), ‘World of Stone’ (Extra Texture), and three mysterious titles- “All Over Love,” “Boxed in a Corner” and “Moonlight Faith.” None of these attempts are included in the set, but the carefully- crafted running order includes:

“Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth),” a long, plaintive chant with an unmistakable slide guitar hook, is one of George’s most timeless pieces of poetry. Bright acoustics and intimate slide interplay with an open hi-hat and an organ swirl, clearer than ever in the new mix. Hopkins’ piano on the second verse gets a real moment to shine. ‘Returning’ from the All Things Must Pass sessions, the George O’Hara-Smith Singers-George, stacking his own vocals- fill out the backup vocal sound. An outtake, released in advance of the album, highlights the strength of George’s acoustic songwriting and a more direct, playful vocal set against a shimmering guitar.

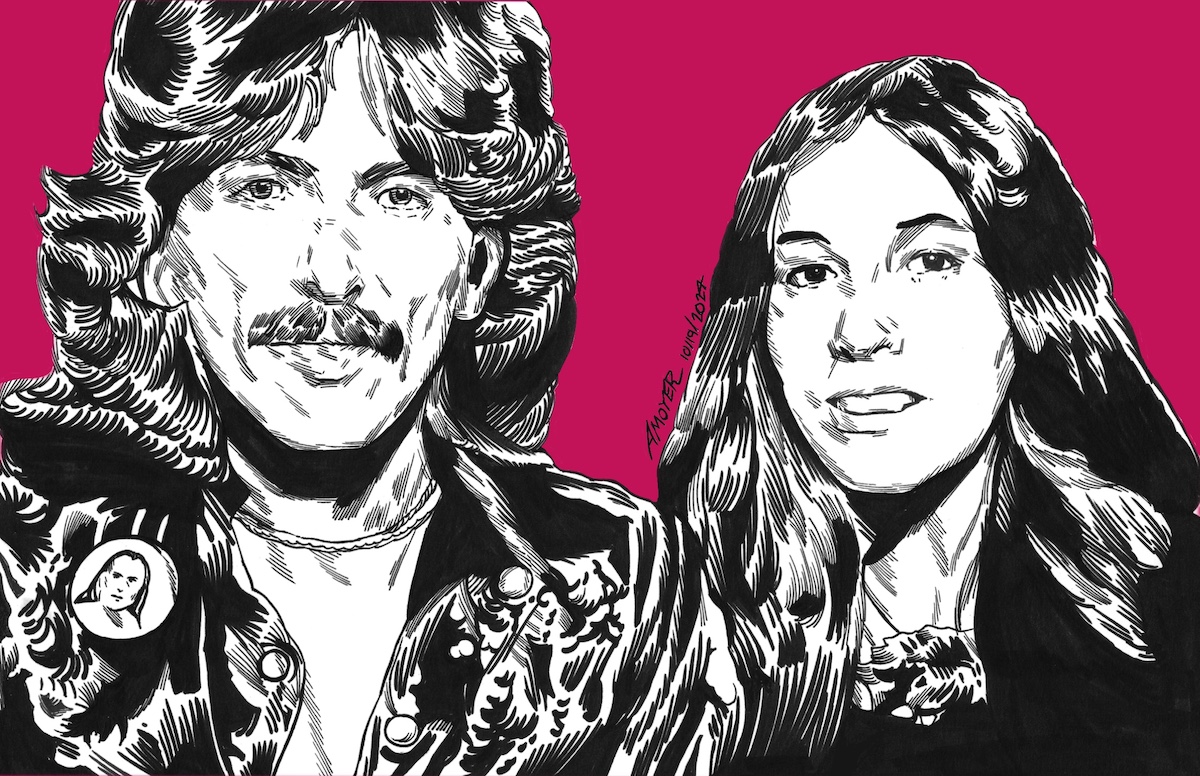

In the summer of 1973, “Give Me Love” took the top spot on the Billboard charts, replacing Paul McCartney’s “My Love.” Across the pond in LA, a 22-year-old woman was working A&R for A&M Records and hearing an unmistakable slide guitar over the airwaves. Not 18 months later, Olivia Arias would join Harrison on the Dark Horse Tour and remain his partner for the rest of his days.

A demented do-see-do rife with Harrison humor, “Sue Me Sue You Blues” is mired in the legal drama of Apple Corp., Bangladesh, and a dispute over My Sweet Lord’s resemblance to the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine.” The stars of the show here are the frenetic, skittish drumming from Jim Keltner and George’s biting bottleneck slide which was all over Lennon’s Imagine record in ‘71. It serves as a companion to Lennon’s How Do You Sleep: “hold your bible in your hand/all that’s left is to find yourself a new band.” Electric piano trills and tom-tom fills are clearer here, as is a groove ride cymbal pattern in the third verse. On the outtake, there’s a rare treat of hearing Harrison hashing it out as in- studio producer:

“Actually I think you’re going to have come in right at the top Jim, with at least something, or at least keeping the time or… ’cause I count in and you were going so much faster.”

The band is loose and playful, with George singing “a-sue, me, a-sue you” in a mock twang over a looser rhythm. When this track appeared in the Dark Horse tour set the following year, Harrison sang “bring your lawyer, and I’ll bring [Allen] Klein.” The various suits herein lingered throughout the 70s and, in a brighter moment, reappeared in “This Song.”

Shifting gears to the soulful, one of George’s standout slide compositions graces “The Light That Has Lighted The World.” Critics cited a ‘preachy’ streak to some of Harrison’s mid-‘70s songwriting, but there is a genuine pain as Harrison addresses the fallout of his post-Fab pursuits:

It’s funny how people just won’t accept change

As if nature itself they’d prefer rearranged

So hard to move on when you’re down in a hole

Where there’s so little chance to experience soul

Harrison pitched this as a B-side for Cilla Black, who came up with The Beatles under Brian Epstein’s management. None of them were kids anymore.

In the outtake, a control room voice coaxes “George can you possibly sing on it?” Harrison agrees and adds an effortlessly beautiful vocal over a descending piano line that didn’t make the final cut. The band did their homework on these tracks in the arranging stage and the semi-acoustic versions stand on their own.

“Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long” is perhaps the most confounding entry in the Harrison catalog. A perfectly ebullient sendup of the Brill building sound,its infectious kettle bell- timpani combos, tinkling organ flourishes and an all-time acrobatic and pleading vocal from George, had all the makings of a perfect single. Hicks brings up all the sugary-sweet touches- dual drums from Keltner and Starr, ‘varispeed’ backup vocals, an ascending electric piano, and protracted “ooooooh-aaahs” to round out the sound . There is a notable difference to previous mixes in the chorus; what once sounded like “so don’t let me wait too long, long” bouncing between channels is drawn out as “don’t let me wait to lo-oh-oh-ong.” While the strength of George’s falsetto is evident in plenty of these tracks, the alternate entry of this tune is perhaps its best showcase. Despite its buried placement as the fourth track on side one, it is a genuine classic deserving of a re-airing.

Thirteen years before they joined forces as Wilburys, Roy Orbison shaped George’s performance on “Who Can See It.” Spector’s influence is most audible in the choir, string section and trumpet leads. The tremolo guitar set against an orchestra is evocative of the ‘Let it Be’ album sound of three years prior, including the unmistakable Ringo tom-tom fills. In this instance, the alternate ‘no-frills’ version is the superior one, and showcases the mixed time signatures that George incorporated from the Indian classical tradition.

Harrison rarely gets credit as the first ex-Beatle to genuinely have a laugh about the mythmaking of it all. Yet, against a march tempo from Starr and Keltner, the title track “Living in The Material World” distills the entire saga to:

Met them all here in the Material World

John and Paul in the Material World

Though it started out quite poor,

we got Ritchie on a tour

[Ringo plays a fill]

Tabla player Zakir Hussein accompanies the airy flutes on the bridge, in an East-West fusion that shaped the sound of 1974’s Dark Horse and, decades later, the title track of Brainwashed. In stark contrast to the bombast of the ‘A’ section, Harrison falsettos:

From the Spiritual Sky

Such sweet memories have I

To the Spiritual Sky how I pray

Yes I pray

That I won’t get lost or go astray

Jim Horn’s blaring lead sax veers the sound into SNL house band territory albeit two years early. The blistering lead guitar lines layered with the chugging Voorman-Starr-Keltner rhythm section drive the track into its “blues bar band” outro. If the album version is chugging along, the alternate take is nearly a runaway train- even faster than the final, its grittier guitars and quick shifts to the bridge become all the more impressive. The outtake sounds a bit like Badfinger, whose ‘Straight Up’ features George co-production and slide guitar.

Harrison’s favorite number was seven, and he always slated his favorite album tracks in the seventh slot. It’s a bit curious, then, that the distinction should go to “The Lord Loves The One That Loves The Lord,” a breezy Wurlitzer-led blues with a ‘For You Blue’ feel and ‘Savoy Truffle’ saxophone stabs. The callow humor on display is nevertheless infectious, and an auditory joke newly emerges in the Hicks mix:

We all making out

Like we own this whole world

While the leaders of nations

They’re acting like big girls

With no thoughts for their God

Who provides us with all

But when death comes to claim them

Who will stand and who will fall?

On the word “faaaaaaal,” there’s an echo that evokes a trip off a cliff. Take 3, featuring George quipping “ “that part on the end could be a solo, ‘Que sera’. Could be a sax solo. “Are you rolling, Bob?” is bouncier and more keyboard heavy as the band has a blast. It’s brimming with a joy that cements it as a highlight of the set.

Only two mixes emerged in advance of the album’s release, take 18 of Give Me Love and the truly sublime take 8 of “Be Here Now.” Shaped by the writings of yoga pioneer Ram Daas and his eponymous book, a new lyric video illustrates a lovely and direct poem:

Remember now

Be here now

As it’s not what it was before

The past was

Be here now

As it’s not what it was before

Why try to live a life

That isn’t real no how

A mind that wants to wander ‘round a corner

Is an unwise mind

An ode to mindfulness with one of Harrison’s best-ever double tracked vocals , the song is largely built on an organ drone paired with an acoustic guitar . Eastern scales are woven into the sonic tapestry on the oscillating phrasing of “he-e-e-ere now”; Occasionally , tom-tom rolls and a twinkling piano fill out the mix and the warmth that George captures is reflected in reams of loving YouTube comments below The Newton Agency’s animation.

Clearly, the Gallagher brothers also loved this track. And, in the vein of famous admirers:

Bowie apparently didn’t realize this was a George Harrison composition when he fell in love with the demented carnival that is “Try Some, Buy Some.” Featuring an erratic chord progression and cryptic lyrics about finding God in the midst of alluring libations and full-blown Wall of Sound orchestration, the track initially took shape during the All Things Must Pass sessions. Intended and released as a comeback vehicle for Ronnie Spector, Harrison took a crack at the vocal himself in the original key. Omitted from the final mix but resurrected in its alternate take is a striking slide guitar.

“The Day The World Gets ‘Round,” much like “Who Can See It,” draws from the sonic well of the Let it Be album ; though Harrison often bemoaned the vibe of those sessions, this would not be out of place sequenced after ‘Across The Universe.’ Eschewing the horn stabs and bombast of the final version, take 22 showcases a powerful Harrison vocal on the bridge section. Stripped down to their essentials, the songs on LITMW stand as well-composed, well-sung and well considered in their arrangements and time signature changes.

This holds true for “That Is All,” a closing track with the loungey feel of 1975’s Extra Texture. There’s no more succinct mission statement for this record than ‘That is all I want to say, our love could save the day.” George’s falsetto is set against a tinkling harpsichord, Leslie-speaker guitar and floated-in double track vocals. Take 24 features an alternate opening lyric –

That is all I want to say, a smile from you each day/ that is all I’m waiting for when I come through that door

– which seems to be directed at a lover.

“Miss O’Dell,” AKA Apple Corps. secretary Chris O’Dell, gets a lovely send-up on a B-side that stands as a breezy contrast to the weightier themes of the album proper. Led in by a cowbell and harmonica, Harrison opines,

I’m the only one down here who’s got nothing to say

About the war or the rice

that keeps going astray on its way to Bombay.

That smog that keeps polluting up our shores

Is boring me to tears.

Why don’t you call me, Miss O’Dell?

The vibe is so loose that Harrison laughs aloud multiple times, immortalized in the final take alongside an offhand ad-lib “Garston six-nine-double-two!” This was the childhood Liverpool phone extension for Paul McCartney’s house.

One final surprise remains: A Harrison hoedown backed by The Band, “Sunshine Life For Me (Sail Away Raymond).” Peace and Love to Ringo, who recorded the final take on his eponymous 1973 LP, but the bevy of backing vocals and the plucked banjo and Gaelic fiddle combo cement this as the ultimate version. It’s harder to parse in its lyrics, but this is the sister to “Sue Me, Sue You Blues.” Raymond was a lawyer in Allen Klein’s employ, at the center of the London High Court acrimony as the Beatles dissolved. Harrison yearns for an escape:

Now most folks just bore me

Always imposing

I’d rather meet a tree

Somewhere in a cornfield

A quarter-century since George Harrison walked the grounds of Friar Park, the gardens remain immaculately preserved by his family.

Though he was unable to revisit his full solo catalog, the fruits of his musical labor are equally well-tended. Recently, Dhani Harrison confirmed that Peter Jackson is spearheading a remaster of the Concert for Bangladesh; there is a complete concert film of 1974’s Dark Horse tour in the vaults as well.

Hopefully this and the remaining entries in his canon are presented with the same care as Hicks provided this collection. These glimpses of George’s spiritual world and creative process are precious and rare, and his legacy could not be in better hands.

Living in the Material World is available to stream on November 15, 2024.

— —

:: stream/purchase Living in the Material World here ::

:: connect with George Harrison here ::

— —

— — — —

Connect to George Harrison on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Aidan Moyer

:: Stream George Harrison ::

© Aidan Moyer

© Aidan Moyer