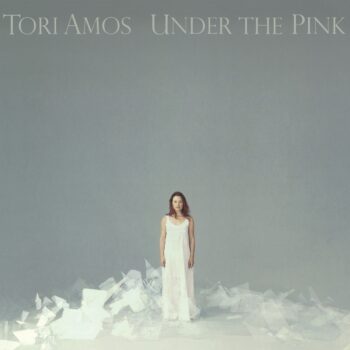

Singer/songwriter Tori Amos tackled themes of sexual violence, religious allegory, and anti-victimization with cool conviction in her second studio album ‘Under the Pink,’ released on this day in 1994.

by guest writer Emma Schoors

Stream: ‘Under The Pink’ – Tori Amos

In February 1993, Tori Amos moved into a New Mexico hacienda with her then partner and producer, Eric Rosse.

Just a year prior her debut record, Little Earthquakes, soared to #1 on the UK charts, landing her smack dab in alternative music’s fickle epicenter. Following the likes of “Silent All These Years” and “Crucify” would be a challenge without some preemptive grounding – the vast Southwestern desert was where she would find it.

It was here she would develop a lung infection that threatened to take away her singing voice for good. On the flip side, a local Indian tribe would take her under their wing as an honorary member. “There was something about it… something really rugged and raw,” Amos told the Baltimore Sun of her time out west. Detached from the hustle and bustle of major music scenes, the record that resulted, Under The Pink, drew from a deep well of literature, cinema, and her own experiences.

Opening track “Pretty Good Year” was written when Amos received a letter from Greg, a slender man with scrawny hair, glasses, and a “great, big flower” drooping in his hand, as per the enclosed pencil self-portrait. “Greg is 23, lives in the north of England, and his life is over, in his mind,” Amos recalled in a 1994 interview. “You don’t really know what my role is [in the song.] Am I Lucy, or am I that eight bars of grunge that comes out near the end?”

Tears on the sleeve of a man

Don’t want to be a boy today

I heard the eternal footman

Bought himself a bike to race

“He writes letters in his birthday pen,” Amos sang, tangible proof of Greg’s life continuing aimlessness and all. Oscillating between a soft, walking piano line and Amos’ fraught pleading atop Carlo Nuccio’s apocalyptic beat, the track lent a heaping spoonful of strength to his precarious situation. “I care about Greg, you know I do. But there’s no pity in the song,” she told The New Review Of Records. “If I pitied him, then that’s really condescending.”

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar explored the paralyzation that comes with young adulthood with the use of her fig tree metaphor. In many ways, Greg saw his life branching out in front of him, too, each possibility seemingly withering as time marched on. “Pretty Good Year” addressed his evergreen potential with the utmost care and attention.

With “God,” Amos turned her pen to the muzzling of Mary Magdalene in modern religious teachings. “Nobody wanted to talk about Mary’s true role. And people don’t really think about how that affected an entire planet, to have the most populated religion worshipping a sexless being,” she told B-Side in 1994. Its goddess narrator consoled God with a few constructive footnotes. “It’s honest and loving, and it’s sensuous,” Amos said to Creem. “It’s the goddess coming forth and saying, ‘Come here, baby. I think you’ve had a bit of a rough job, and I don’t mind helping out now.’ Which I think is really cute.”

Will you even tell her if you decide to make the sky fall?

Will you even tell her if you decide to make the sky?

“Tell me you’re crazy, maybe then I’ll understand,” she offered, describing the heavenly father as having his “nine iron in the back seat,” ready to jump ship “just in case.” In the record’s liner notes, Amos explained the track was written with the intent of questioning the beliefs, as well as the interpretation of God, that rewarded violence and hatred among his children.

“Bells For Her” was recorded with Rosse’s help after a particularly tense day of waiting. The words and music finally came to Amos in a frenzy, inspired sonically by the detuned acoustics in the studio, and conceptually by the dissolving of a friendship she held dear. “You don’t need my voice, girl, you have your own,” she sang, pounding at an upright piano altered by Rosse and Phil Shenale, once again pushing the boundaries of what the instrument is, and what it can withstand.

There’s nothing we cannot ever fix, I said

Can’t stop what’s coming

Can’t stop what is on its way

Upon first listen, “Bells For Her” encroaches on off-putting. The piano is modified beyond recognition, marrying the grace of church bells with the dust and distortion of an instrument long abandoned, yet nearly failing to make sense of the combination. Amos’ challenging of the piano is to her music as a creak is to a step on a staircase, however, armoring it with character and body.

Backed vocally by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails and recorded at the site of the Charles Manson murders, “Past The Mission” saw Amos discover a path forward from sexual violence. “The idea is to rescue myself from the role of a victim. That I have a choice left,” she told the St. Louis Dispatch. “Though I can’t change what has happened, I can choose how to react. And I don’t want to spend the rest of my life being bitter and locked up.”

Hey, they found a body

Not sure it was his, still they’re using his name

And she gave him shelter

And somewhere I know she knows (She whispers again)

Somewhere I know she knows (She whispers again)

Some things only she knows

Where Little Earthquakes’ “Me And A Gun” spoke of survival, “Past The Mission” proved, in Amos’ words, that everything is reclaimable. It also expanded her instrumental repertoire – Amos played a Vox organ during the bridge, paired with Rosse pushing styrofoam underneath the piano strings to create a “strange bassoon sound.”

“Baker Baker” helped Amos admit she was the emotionally unavailable half, the vampire, of her relationship with Rosse. With a passing mention of Los Angeles and a thematic focus on the healing powers of a baker, she reflected: “Well, I ran from him in all kinds of ways. Guess it was his turn this time.”

She shakily resolved that there “must be something here,” that maybe she “can change his mind.” Gutting and gorgeous in equal measure, Amos’ tenor wavered between acceptance and bargaining, sometimes channeling them both in the same breath.

The story behind “The Wrong Band” was that of a sex worker fleeing to Japan after being involved with a Congressman, and becoming privy to information that threatened her life. Seeking to shed light on the danger posed to those in the industry, Amos told the Illinois Entertainer: “When people start judging [them], they should just shut up, because they have no idea what it’s like to be on the other side.”

She’s got a soft spot

For heels and spurs

And there’s something believin’

In her voice again, said

There’s something believin’

Instead of just leaving

Turning quickly from empathy to murderous intent, “The Waitress” came from the shocking realization that Amos could, and for a split second wanted to, kill someone. Engineer Paul McKenna had told her the record was incomplete, and within just 48 hours the events that inspired the track transpired, sending her right back into the recording booth with lyrics that verged on criminal.

If I did it fast, you know that’s an act of kindness

But I believe in peace

I believe in peace, bitch

While not entirely reactive, (she “can’t believe this violence in mind”) “The Waitress” built upon the rancor harbored by Amos at the subject at hand. Just before the chorus, she delivers an off-tune, breathy handful of notes, mirroring a siren or chilling warning bell. This pause makes the payoff even greater, and leaves one wondering just when she’ll return to the thundering main event.

Possessing The Secret Joy by Alice Walker, and its gruesome depiction of women selling their daughters to butchers, inspired mega-hit “Cornflake Girl.” The track completed the trifecta formed by “The Waitress” and “Bells For Her” in their exploration of betrayal within female circles. “One always feels safer when there are good guys and bad ones,” Amos explained to The New Review of Records, “but there are no good guys out there, and it’s not as if one sex can make it okay.”

Rabbit, where’d you put the keys, girl?

And the man with the golden gun

Thinks he knows so much

Thinks he knows so much, yeah

Suffused with rich, multicultural influence, the main groove of “Cornflake Girl” came to Amos on a warm day in England, live reggae pouring through her open window. The Meters’ George Porter Jr. and Brazilian percussionist Paulinho da Costa layered the track with “big sleigh bells” and New Orleans voodoo for some extra flavor.

“Eric was laughing his head off, and the mixer, Kevin Killen, said to me, “This whistle is naff, Tori,” Amos said of a whistle she was dead set on including in the mix, “and I said, “Well, guess what, Kevin. When you make your own song, you can put your own mandolin on it. This is a whistle. Fucking put it in. Put the sample in.”

Arguably the most on the nose track on Under The Pink, “Icicle” plainly described masturbation as a liberating countermeasure to a repressive environment. “Anyone who sees that as blasphemous can go to hell,” Amos told Hot Press.

Greeting the monster in our Easter dresses

Father says, ‘Bow your head like the Good Book says’

I think the Good Book is missing some pages

Considering Amos grew up a minister’s daughter, it wasn’t uncommon to have theologians at the dinner table. While these discussions were happening, Amos was upstairs, as she explained to Oor, “exploring the divine light within [herself].” Self-pleasure isn’t a taboo concept in popular music by any stretch of the imagination, but combining it concisely with religion was sure to step on a few toes within the church.

“Cloud On My Tongue” followed, written for a man who’s let into a sacred corner of the narrator’s heart, only to seek fulfillment in other women. “Even if they’ve never physically touched,” Amos wrote in the album’s liner notes, “he exists within her. Her hope seemed to be that he would value that she had him orbiting.”

Got a cloud sleeping on my tongue

He goes then it goes and

Kiss the violets as they’re waking up

Leave me with your Borneo, I said

Leave me the way I was before, but

You’re already in there

I’ll be wearing your tattoo, yes

What made this song almost unbearably emotional is how simple it was. “The girl’s in circles and circles and circles again,” she sang, submitting to the futile yet endless devotion of having him “already in there.” She assured she’ll be “wearing [his] tattoo,” hinting at being physically intertwined by having slept together, possibly even scarred or made pregnant by him.

In stark contrast to “Cloud On My Tongue,” Amos loosely described “Space Dog” as a vision given to her by a dog painted in mud. Yes, really.

On a flight over Chicago, engrossed in a romance novel, Amos was figuratively spoken to by the dog and shown a boy “talking into his peas” about his dysfunctional family, as she explained during a live show in Holland. The song that came from this vision also mentioned Neil Gaiman, Amos’ friend and author: “Where’s Neil when you need him?”

“Space Dog” is one of the more nonsensical tracks lyrically, but once given some research and thought, a personalized narrative can exist within each listener.

Sick with food poisoning in Richmond, Virginia and visited by Anastasia Romanov’s “blueish-greyish light” of energy, Amos concocted Under The Pink’s last track, “Yes, Anastasia.” Stylistically influenced by Debussy and Russian composers, the song originally included a 50-piece orchestra, which was erased by Amos to the disapproval of her collaborators.

Thought I’d been through this in 1919

Counting the tears of ten thousand men

And gathered them all, but my feet are slipping

There’s something we left on the windowsill

There’s something we left, yes

As an album closer, “Anastasia” left a bit to be desired. Bookending such a personal collection of songs with someone else’s channeled story seemed a misguided move for an artist so in touch with, and so capable of relaying, her own experiences. But to discount “Anastasia” would be to discount “Jackie’s Strength” and “Josephine,” and that would be throwing away three glimpses into the universal throes of femininity.

They aren’t just tales pulled from the bottom of a pile of books. They’re parallels to the ways in which all women exist, and the hurt we all endure, both at the hands of others and of ourselves.

When Riot grrrl giants Hole, Bikini Kill, and Sleater-Kinney overtook the punk underground in the early ’90s, vengeance was at its forefront.

Brash guitars and full-throated screams bought back the power stripped from female-fronted acts by a largely male-dominated scene, and for good reason. The one thing an album like Hole’s Live Through This, released the same year as Under The Pink, sometimes failed to recognize, was the inner child cowering under that bloodlust.

Anger is a valid stomping ground for a little while, but it gets old. Amos met that temper with a kiss and a practical solution. She sang as if it was a cloud passing through, or rushed straight to sadness’ side, understanding the road leads there anyway.

Amos is capable of singing of rage, of course, and there were a handful of songs on Under The Pink that provided it room to roam, like “God” and “The Waitress.” B-side “Honey” was “the blood” of the record, for example, though it was booted in favor of “The Wrong Band.” But the empty space left by “Honey” – or by fellow rarity “Daisy Dead Petals,” for that matter – gave it an echo that has reverberated through three decades.

Turn one last time

Love to watch those cowboys ride

But cowboys know cowgirls ride on the Indian side

And you know what you’re doing, so don’t even

You’re just too used to my honey now

Under The Pink was hyper-specific in its truth-telling, but it also came equipped with a fascinating required reading list.

It wasn’t the first time Amos would step into the shoes of historical figures or close friends in order to tell a story, and it wouldn’t be the last, but it was the first time she was able to look back on a section of her career and write about it.

With one body of work under her belt, Amos could’ve easily settled into the safety net of sound Little Earthquakes had created. Instead, she challenged everything she knew – about herself, and about her work – to create something extraordinary. Thirty years on, it stands as a sonic testament to adaptability, strength, and the power of womanhood, for better or worse.

— —

Emma Schoors is a 20-year-old music journalist and writer based in Southern California. When she’s not interviewing rising names in alternative rock, Schoors can be found on the open road exploring countrywide music scenes, food, and culture.

— —

:: connect with Tori Amos here ::

— — — —

Connect to Tori Amos on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© Tori Amos

:: Stream Tori Amos ::

© Tori Amos

© Tori Amos