In this unflinching account of an album release gone terribly wrong, Indiana-based Joey Walker describes his struggles as a solo artist, living within the cultural periphery, and why he’s ultimately leaving music behind. Atwood Magazine chose to share this essay not only because it highlights an all-too universal issue, but also in the hopes that those who read Joey’s story know that they’re not alone in what they’re going through.

Stream: ‘Inferno’ – Joey Walker

On January 28th, 2022, I released Inferno to absolutely zero fanfare.

Despite months of unsolicited emails to small record labels and even smaller music publications, nobody responded. It contained three songs and its total runtime was 13:28. And it cost me about $5,000.00 altogether. Oh my god, where did I go wrong?

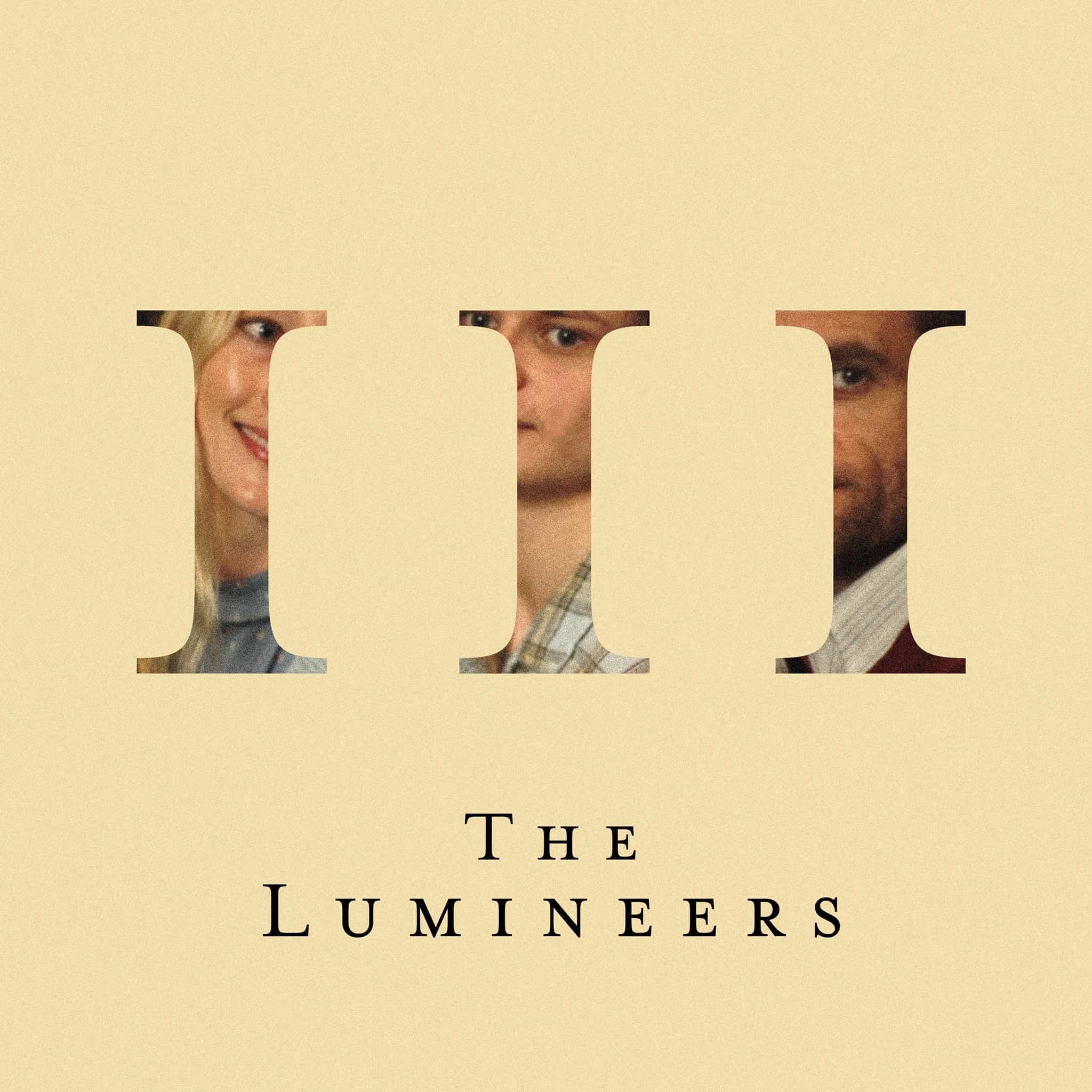

I think I could’ve lived with the comparisons to Xiu Xiu, (a band I’ve never listened to), or Perfume Genius, (a musician I respect but ultimately don’t enjoy all that much), if it meant I could attain a modicum of listeners and a few engaged fans. Those comparisons came as a result of my second full-length album, Supersoft, which was released in January 2019. We, (being myself and my former label), dubbed it “twink rock” as a marketing ploy. It was a half-hearted joke about my own body and homosexuality that I thought might turn a few heads and playfully nod to the libidinal economy that ruled over much of the music business.

Armed with this fake genre, I also had a publicist for the first time ever. We managed to get a few reviews and a couple interviews here and there. It was the first time anybody truly critiqued my music, and despite it costing more money than was probably worth, I grew to be thankful for this experience. I must give props to Leah Levinson at TinyMixTapes for picking up on my little joke and giving an entirely fair assessment of the music. But I felt rather limited in the immediate aftermath. I thought any momentum I had hoped to build for my music career was going to be based around a silly joke, (or even worse, my sexuality); that it would be a constant game of marketing strategies to carve out the tiniest of niches. Once an internet commenter earnestly declared my music as “fantastic twink rock,” I knew I had made an error I would later need to rectify.

Stream: “The Light” – Joey Walker (from ‘Supersoft’)

On a regular basis, I would come up with concepts for future albums and songs amidst my daily daydreaming. I stored them away in my notes as [TO DO ONE DAY] and usually never returned to them. However, there was one idea that always stuck with me; I wanted to make an album that dynamically started soft and ended as harsh as possible. I imagined an album that would span across genre — from orchestral ballad to harsh noise — to leave the listener with a memorable, albeit linear, experience. I wanted to span the facets of chamber pop to indie rock to post-rock to drone metal, ultimately to prove that my chops as a musician and songwriter could handle any aesthetic clothing I wanted to wear. And eventually I did write that album.

It was called Oblivion and a few individuals out there have heard that demo album. (What a cruel joke it must be to have your greatest artistic failure literally be titled Oblivion.)

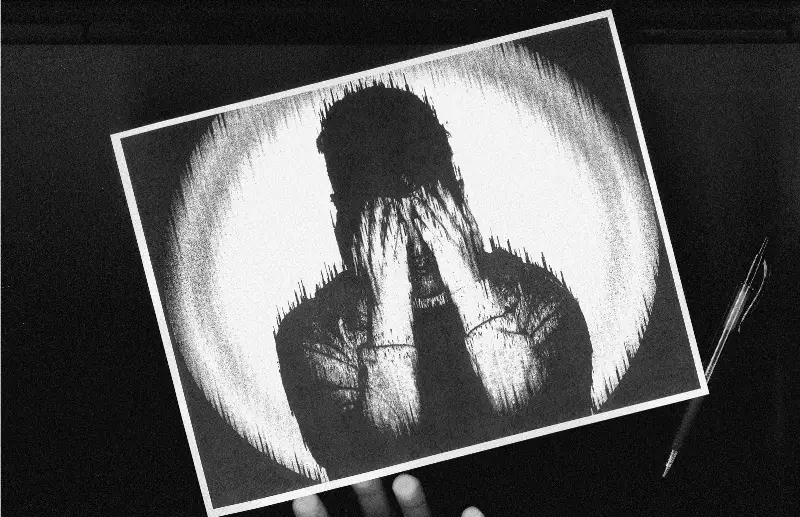

Describing the album in this way makes it all sound a bit corny, but it was a journey through hell , the kind of existential hell you might experience when you realize that all the love in the world will never fix you. Through those songs, I confronted my demons and entered the death dimension—the nihilist abyss—and mined myself for all I was worth, which ended up being nothing. The album was to culminate with so much noise that the self and all its detritus was erased, proving that the resetting of identity was, perhaps, possible if only through death, artistic or otherwise. The epic spanning of genre was also to further this point — that no matter where I tried to hide, the conclusion would always reach the same logical end. If Supersoft limited my own experience as a songwriter through its fabricated genre, then Oblivion would completely untether me, to allow the freedom to go wherever the music would take me. I didn’t know of any other albums that had attempted this concept; it felt like uncharted territory, which I knew would turn many people away. I believed, with the right amount of development and support, it could be a standout in the indie music realm.

In all fairness, my demos were not very good. All my placeholder orchestral arrangements were midi instruments, the lyrics weren’t finalized, and all my rough takes sounded akin to exposed cracks in foundational concrete. I forwarded them to record labels and others in the music industry anyways. I didn’t expect any responses, but the few I did receive plainly refused to listen. Though I wasn’t quite deterred yet, since the demos were only sketches of what I intended to create no matter what.

I had countless conversations about Oblivion with my then record label, Darling Recordings. Eventually we reached the conclusion that it was going to be a lot of work and would probably be very expensive. If I had asked, perhaps they could’ve helped achieve my vision, but I wasn’t sure how to ask a one-person operation, struggling to run their own passion project, to help fund mine. So I eventually came up with the idea to record and release the first three songs of the album as a teaser for the full-length record, entirely by myself. Since the album’s tracks were so linear, presenting these songs in order wouldn’t be out-of-place and could theoretically be appreciated as a complete statement all its own. Since I had been inspired by Dante’s descriptions of hell in Inferno, I decided to borrow this title for the EP. At this point in time, it was early 2020 before the world really fell into an inferno. And just as I had started to get everything aligned, I realized it would not be happening as I envisioned; nevertheless, I was stubborn and determined.

In April 2020, I met (over Zoom) with a local Ph.D. student in music composition whose name I had found on a program from a concert in 2019. I intently listened to his work and felt resonances within his vision and hoped he would work with me. He agreed to help flesh out my rudimentary orchestral arrangements for $500 per piece, and this was the best investment I made during this process. It was extremely gratifying to work with someone who understood the aesthetic world I was attempting to create, as I never had that in my 15 years of being a songwriter. Those arrangements took the better part of the year and weren’t completed until January 2021. Suddenly, it was then my responsibility to get everything recorded — except I didn’t play violins or flutes or saxophones. I had never asked other musicians to ever play on any of my music and I did not realize how expensive this would eventually become.

After scouring the internet for musicians who could record themselves remotely with high-quality equipment, I found someone who could do all the woodwinds and saxophones at an unbelievably reasonable rate. He also helped me find someone to record the brass parts on the third track, “Evangelist.” The string quintet for the first song definitely wasn’t as expensive as it could’ve been. And a friend recorded the drums for me for a small fee. I’m glossing over much of the monotony involved with each of these because it isn’t particularly interesting — I reached out to musicians and paid them for their work.

Individually, everyone I worked with set reasonable prices, but this contributed to the bulk of my expenses. A new sense of dread set in — if I still needed to arrange orchestration for the other 6 songs on the LP and it had already cost me $3,500.00 for this 3-song EP… things weren’t looking great. I tried to suppress my anxiety but I burst apart— I would continue work on the music, but I had to accept that my full-length album would never see completion. There was a flicker of hope that Inferno would attract decent press and perhaps more support and development for the album, but my pessimistic mood persisted. I tried to move on and maintain the best outlook I could, but I knew I was already too deep into my mistake.

The next part of the process was the production and mixing of these three tracks. I had previously worked with my old internet pal Nick Pitman on a one-off single in 2020, so I knew I wanted to continue this work with him. Since he had a home studio, we didn’t have to arrange professional studio time or even be physically present. We used the advances of modern technology to collaborate by streaming our computer screens via Discord so I could hear mixes in real-time and suggest adjustments. We started mixing in June 2021 and finished at the end of October 2021. Mastering was completed quickly after I had the final mixes.

Stream: “Evangelist” – Joey Walker (from ‘Inferno’)

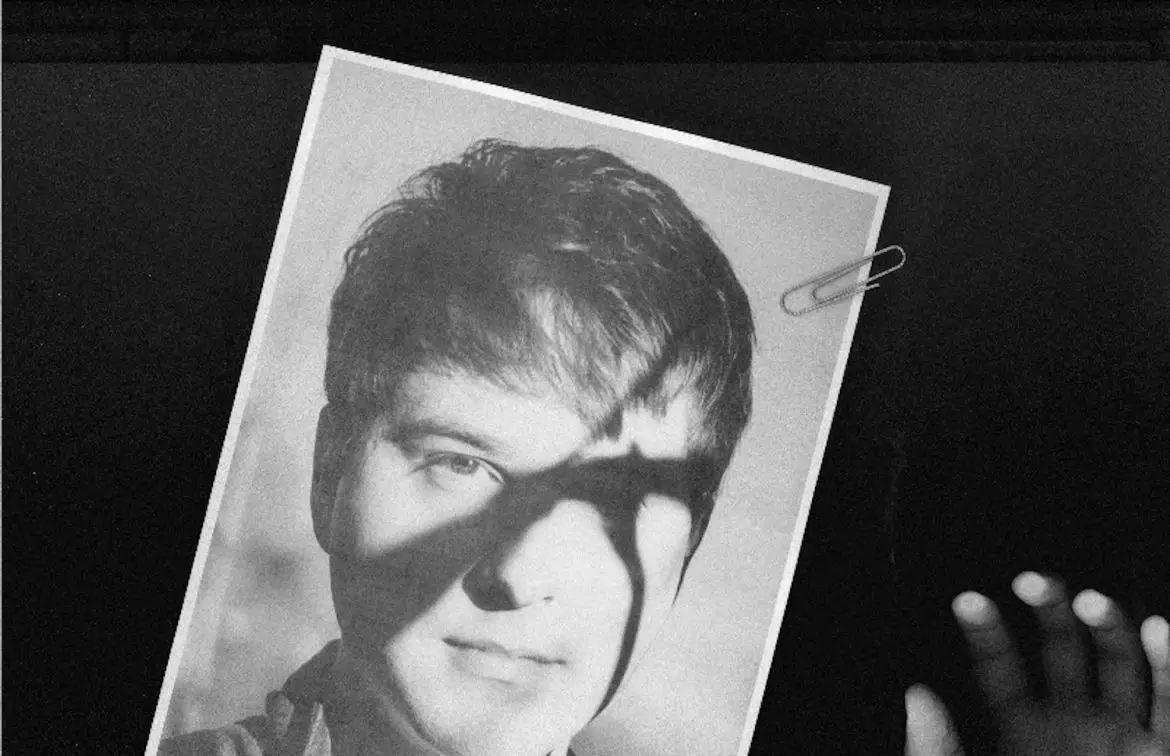

Then came time to create the visuals to my musical creation.

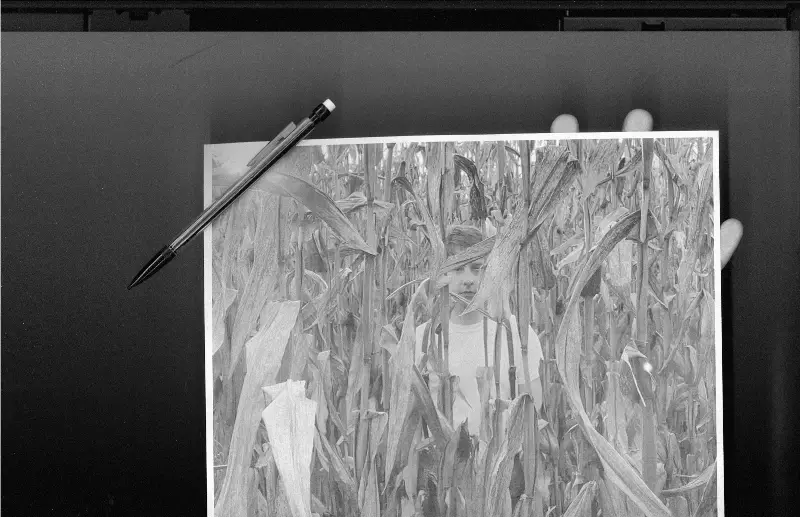

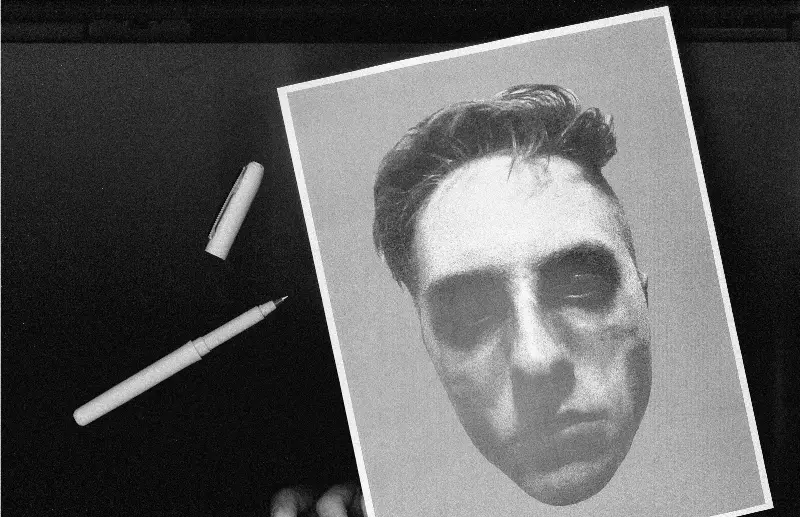

I’ve always struggled with putting my face to my own music — something about a desire to let it speak for itself on its own terms. Supersoft was an exception that I did not want to repeat. I recall being inspired by Children of the Corn and also Days of Heaven, wanting to replicate the sense of dread both films brought in their own special way. My home state, Indiana, is filled with cornfields, so I thought I would represent my own midwestern hell in this way. I bought black fabric and a mask and evoked my strange dance in front of my iPhone camera. At this point, I was too depressed at my lack of prospects to be as visually creative as I wanted to be. I edited the footage myself, learning Premiere Pro as I went.

Was I happy with how it had all turned out? Mostly ; after all was said and done, I was pleased with the music itself. There were things I wish I could’ve changed about the visuals, but they were either minor or unrealistic. Inferno contained my best songs to-date and my voice had never been better. Music that I had begun to envision back in 2018 was finally reaching completion just before 2022. Four-or-so years I had been planning for this moment. I planned a January release date, since I didn’t want to linger on these songs for longer than I had to. But how did I feel at that moment? Immense regret. Impostor syndrome. And it was going to get much worse.

Once the music was finally done, I genuinely had to stop and ask myself, “How will I afford to do any promotion… or can I do that on my own?”

Hiring a publicist would cost at least another $500 to $1,000 on the low end, and my previous PR experience was somewhat fraught. When would it be enough? Already indebted by $5k from this project, I decided to do my own promotion.

It had always been progressively getting to this point, but in 2022 you would never get a response from a music journalist or a music publication if it wasn’t through a publicist. Perhaps independent musicians still had a chance in the early 2010s when the blogosphere was hungry for the next hooky song to feature. But that was then; musicians now are essentially self-start-up businesses where you need a cash influx of thousands — if not tens of thousands — to jumpstart a career beyond your zip code. And even if you are able to secure that, either through lots of work or your wealthy family, it’s not guaranteed that you will be much of a success. To quote from an article on the ‘blog era’ by Tim Larew writing for Complex:

The currency in the blog era was press coverage, interviews, and general chatter. Today, it’s attention by any means necessary… As the blog era has become increasingly distant in the rearview, I’ve found many upstart artists and managers feeling increasingly helpless or on their own when it comes to trying to get music off the ground.

The era I started making music in was far gone, but I was still operating as if it never left. I also wasn’t sure how to market songs about loving the devil on TikTok and other platforms. Ultimately, as a working class, nearly-30-nobody living in a midwestern flyover state, the cards were likely always stacked against me – they were when I started on this musical journey as a teenager – and that haunts me irrevocably.

I reached out to those who had written positively about Supersoft, but none responded. I tried to contact my former publicist for advice, but he never got back to me. I got a Mailchimp account and put together the best press release I could, writing all facets and blurbs myself. I started by making deliberate choices, emailing sites and writers that I was familiar with and thought might listen. After I was ignored by those options, I turned to SubmitHub. For those who haven’t had the displeasure, SubmitHub is a promotion website where you can submit your music to blogs and publications by purchasing credits. The publications get a small percentage of those credit sales by listening and responding to submissions, with most submissions being 2 credits. It essentially attempts to erase the publicist out of the music industry and allow musicians to also become their own spokesperson, (which is obviously a recipe for disaster.)

I was rapidly descending through the stages of grief. I was purchasing credits on SubmitHub in $10 increments, submitting to any place that covered music remotely close in genre to mine, obsessively checking if a publication had clicked through or hopefully listened. The rejection feedback I received was sometimes positive, sometimes misaligned, but usually generic. I started pleading, “I just want one publication to give me press for my EP. That is all I want.” After spending about $70 on submission credits, and in a very miserable state, I gave up. I wasn’t going to be granted any respite — nobody was going to review the music.

I was heartbroken. Supersoft got press on the back of a joke — the feigned display of a stereotype and trendy sexuality. When I tried to present the truest distillation of myself on Inferno, nobody cared. Middling, inaccurate, or even negative criticism would’ve been better than the nothing I went so deeply into debt for. It felt like a full and unwavering rejection of my identity as a person. Which is sort of funny, because that was the goal with Oblivion all along.

For a while, I maintained that my lack of funds was the main issue for why Inferno was a failure. The music industrial complex, with its networking and nepotism and money, was the problem, while I languished in the cultural periphery of queerness and the American Midwest. It took many months to realize that I could deflect blame onto all my external encumbrances until the end of time, but the core was myself and my foolish passion for music. Simple music.

I eventually found the unfortunate truth Jenny Hval sang on “Jupiter”:

Sometimes art is more real

More evil

Just lonelier

Just so lonely

It is very difficult when your failures collapse on you all at once with nowhere else to hide. It was worse for me, then, when I realized that my art-making, my pointless creative endeavor, was the very cause of my misery. It always had been. When I made music under a different name in high school and early college, I was always disappointed in myself when I couldn’t accomplish what my imagination invented. My previous musical output was always marred from my lack of quality equipment. I had to use the sound recorder on my cheap digital camera to record vocals. Everything I made had a strange hunger to it — desire to fully realize my potential; desire for critical attention; desire for musical connection. But the introverted and sensitive artist within me never was sure how to reach others—the ambivalence to criticism and creation wrestled within me.

Why music? And what even was music? For 15 years I tried to be a conduit to that angelic source of inspiration. To paraphrase a conversation between Fiona Apple and Quentin Tarantino, creativity was like holding an antenna up to the sky and hoping lightning would strike.

But I didn’t want to hold up my arm any longer. I decided to quit.

On July 21st, 2022, I released the final song from Oblivion as a goodbye to anybody out there still listening , a farewell transmission.

I had traveled through the death dimension and come out the other side of hell — the roof of the world studded with stars — and realized that music just wasn’t worth it. Nothing would ever be worth that much personal misery again. I never cried while writing this; in fact, I felt overjoyed to exorcize this from my life.

I would like to say I’m forever closing the door on music and walking away from it for good, but that’s a cliché I try to avoid. Perhaps I’d like to leave the door open, just a little bit? But maybe it’s for the best that I don’t.

What if I simply vanished instead? Into thin air.

If I vaporized while taking a shower? Like nothing was ever there.

If I started walking and never turned back? Like we never knew.

Joey Walker was the moniker of musician, poet, and writer Joey Wańczyk from 2013 to 2022. He previously made music as The Audacity of Youth from 2007 to 2013.

His music is available at joeywalker.bandcamp.com and on any streaming service of your choice.

— —

Stream: “Death Dimension” – Joey Walker’s final single

— — — —

Connect to Joey Walker on

Bandcamp, YouTube

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

? © Anna Powell Denton

:: Stream Joey Walker ::