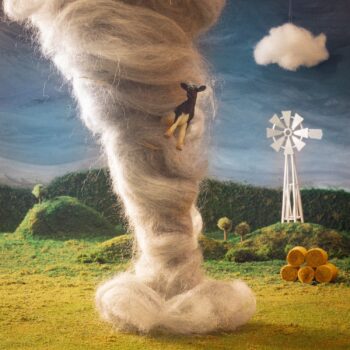

Brief and blistering, ‘Peak Experience’ finds Sydney Sprague and her band pushing their already exuberant sound to include synthetic textural elements and fascinating production techniques.

Stream: ‘Peak Experience’ – Sydney Sprague

If you don’t want me, what’s the point.

* * *

And it is a terribly bleak line.

No matter when it would arrive. Either within the context of an album, as a whole, or placed within the confines of a single song. It’s sorrowful. Dejected. I stop just short of saying it leaves one with an uneasy feeling, but there is a kind of uncomfortable shadow it casts, and we, as listeners, are left standing in it.

I think that’s the point, though.

And it is the last thing you hear singer and songwriter Sydney Sprague utter on her third full-length album, Peak Experience. It isn’t the very last thing you hear before the album’s final song, “Your Favorite,” comes to an end – no. That is the glitchy, jittering digital warbles and squiggles, organically finding their way towards a conclusion. But before that. Right before that. She quietly, morosely sings the last few lines.

“I can see your point of view,” she concedes in the final seconds of “Your Favorite. “Reading Rainbow context clues. I don’t think I’m paranoid – if you don’t want me, what’s the point.”

And that is a theme, or a concept, that Sprague has often written about in her previous efforts – or, perhaps, it is the place that she often writes from. One fraught with anxiety and self-deprecation. One plagued with an existential dread.

“What’s the worst that could happen,” she asked, four years ago, on the clattering “Staircase Failure,” from her enormous and bombastic debut, Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World.

“I just think the worst – think about it all the time,” Sprague confessed in the album’s stunning titular track.

And there is a playful, or sardonic kind of nihilism. It’s a joke until it is no longer a joke but it becomes increasingly difficult to tell where the line is supposed to be.

What’s the point.

And we laugh about it now, but my best friend more or less bullied me out of my nihilism. Or, at least, being as vocal, or as forward about it, as I had been for a number of years.

I understand why she did it. It was certainly one of my least charming, or endearing qualities. The joke until it is no longer a joke. My, at one time, well-documented flimsy relationship with mortality – sardonic and playful until it wasn’t. The kind of affect that found me, among other things, quietly scoffing at the notion of reaching the age of retirement. In the annual meeting between myself, my spouse, and our financial advisor, while nodding my head and trying to look interested in the charts and figures presented to me, and appear excited at the idea of working and saving and investing for another 30 years, my mind would slowly wander into the darkest corners.

“You’re on track to retire at age 70,” our financial advisor explains in a Zoom window on my laptop.

All I can think, though, is what are the chances I am actually going to make it that far.

What are the odds that this planet is going to survive, or be inhabitable, in another 30 years.

A joke until it is no longer.

What’s the point.

There were the years when, partially in jest, partially in earnest, I found myself saying things like, “Nothing matters, and we all die alone.”

And it is, of course, difficult to remain hopeful. Sometimes it feels like an impossible ask. That things, both at large, yes, but even just, like, personally, are going to feel different. Are going to get better. Be less heavy. Not as bleak.

There were the years when things felt the heaviest, and the bleakest. I turned 42 recently – another age I am surprised I made it to. Because there was a long time when I was simply uncertain.

I just think the worst. Think about it all the time.

A joke until it is no longer.

It is difficult to not even remain hopeful but to find a sense of hope, or optimism, at all, when what you have mostly known, for so long, feels so hopeless.

What’s the point.

* * *

Something that I find fascinating, and I think is one of the things that keeps me genuinely interested and often excited about contemporary popular music, is the opportunity to watch a relatively new or an emerging artist continue to grow.

A “career” or any kind of longevity in music is not assured, or promised. For myriad reasons, a band, or artist, can make only one, maybe two albums, and then disappear. So it is impressive, really, when you think about it, that it is something that can be sustained.

Sustainability, though, does not always mean growth, or development in sound, or scope, or even as an artist, which is why it is so exhilarating, and compelling, when you can tell, from album album, that the artist, or band, in question, is continuing to push, or challenge themselves in the art they make.

Peak Experience is Sydney Sprague’s third full-length, but it is the first she is releasing as an independent artist – following a series of self-released EPs, she issued both Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World and its daring follow-up Somebody In Hell Loves You, through the Italian imprint Rude Records. Peak Experience is also her shortest album – a spry eight songs total, it runs no risk of overstaying its welcome and arrives at, like, 20 minutes and change. But Sprague, and her band, waste none of the time they’ve allotted for themselves, because it is a collection of songs that continues to propel itself forward through a kind of blistering sense of immediacy.

Since her debut full-length, Sprague’s music has always had a kind of exuberance to it. That exuberance, or energy, makes it, at times, hard to describe or pin down, if you are looking to categorize. You could call it guitar-driven power pop. You could say that there is an emo-adjacency to it, at times – and this has probably helped Sprague land supporting slots over the last few years with Spanish Love Songs, Jimmy Eat World, and Dashboard Confessional.

You could, if you were so inclined, call it “bubble grunge.”

The songs, however you categorize Sprague’s aesthetic, are always meticulously crafted around an enormous hook – leading us towards an anthemic, shout-a-long chorus. And even though she has just eight songs on Peak Experience, there are plenty of these moments here.

Something that I find fascinating, and I think is one of the things that does keep my genuinely interested and excited about contemporary popular music is the opportunity to watch a relatively new or an emerging artist continue to grow. And there was enormous growth between Sprague’s debut and its follow-up. The songs felt tighter in their structure, and what I think was most noticeable, and is most resonant, is how high the stakes felt. Somebody In Hell Loves You was a gradual step forward, with things feeling a lot more focused, or precise.

Sprague has continued making those gradual steps forward in sound, and in scope, on Peak Experience. The album’s advance singles – three of the four released prior to the full record’s availability- find Sprague and her band continuing to push the guitar-heavy, pop-oriented sound as far as they can.

Elsewhere on the record, though, there is more experimentation – nothing drastic, to the point of alienating a listener. But there are places on Peak Experience that explore crunchier textures. It is by no means a “cold” album, but there is an iciness, or a chill, to the way that Sprague has started to incorporate more programming, synthesizers, and other assorted noises and tones. These songs create a kind of juxtaposition, then, in how the record is sequenced – the guitar-focused bombast that we are familiar with, and these more layered, inward-turned moments that show the growth, or development, that has occurred over the last two years.

Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World was, of course, an enormous and bold artistic statement upon its arrival – and Sprague’s work since then has remained bold, and only grown sharper in both how she uses the subtlest kind of humor in her lyricism, and in the arrangements she is favoring.

* * *

Peak Experience does open with one of its most blistering songs – the breakneck, self-effacing single, “As Scared As Can Be,” but it quickly takes a solemn turn with the melancholic trudge, “Critical Damage.”

It is the first of a few more insular moments on the record, it also is the place where she slowly introduces the more atmosphere, or synthetic textures and flourishes – here, they appear in the form of a rushes of noises that flutter in between the first chorus and second verse, as well as a very intense, dramatic synthesizer tone that rings out early on, punctuating Sprague’s lyricism.

It is a song that, across its two-and-a-half-minute run time, hinges itself on a sense of restraint, or tension, that is never really released. And this is something that Sprague started to explore more on Somebody In Hell Loves You, and continues to do so here – this kind of sorrowful, gritted teeth Sprague uses throughout Peak Experience. Her voice is gorgeous – delicate, full of character or charm, she does know how to make it soar, which is what she opts to do less of on this record. So as the percussion snaps and clatters, and the slow rhythm chugs forward, both with thick bass notes and the bright clanging of the synthesizer, and the distended crunch of the electric guitar, Sprague does sing in a kind of deadpan that does, at least, serve these lyrical observations well.

Sprague can often be direct, or at least a little less ambiguous in her writing, but here, there is an intentional vagueness as she begins. “Cover up my eyes – I can’t watch the car chase,” she begins. “I need to sweat it out,” she continues, before slipping in the subtlest, very niche joke. “I need to call it by its name – by its government name.”

And it is kind of introduced in the album’s opening track, but by “Critical Damage,” she returns to an idea, or an expression, that is something mentioned in a few other places on Peak Experience. “Could it be worse,” she asks in the chorus. “Yeah, I guess. It’s the corruption and I’m just a girl in distress – too dumb to function. Taking critical damage, I’m facing certain death.”

Just a girl.

She uses this self-deprecating line, word for word, in the glitchy, skittering “Dead’s in the Van,” the album’s third track.

“Dead’s in the Van” is a surprisingly tightly wound song, musically – it doesn’t feel like it is going to burst, or anything, but there is like, very little room to breathe in how meticulously it is constructed. But even in that tightness, what makes Sprague such a clever and thoughtful songwriter and performer is the sense of whimsy that still has the chance to ripple through the pinging of the drum machine’s rhythm.

The tension, and sadness, or at least melancholy, that “Dead’s in the Van” strikes in tone – both in Sprague’s writing, and in how these verses are underscored, lifts slightly in the chorus, where there is a mid-air collision between something dreamy, and something a little dark. The dreamy, or hazy feeling, comes from a little rush that occurs at the start of the chorus – an atmospheric element that quickly dissolves, and the vocal melody, too, adds to this with Sprague still singing quietly, but in a higher register. Her voice though is manipulated through production effects – there is a slight metallic clang to it, reverberating through, and it is mirrored in an additional layer where the pitch has been lowered, which sounds both a little silly, and a little ominous.

Even though it is dressed up with a little theatrical exaggeration, there is real poignancy to Sprague’s writing here in how she dissects her experience as a woman in music, but she does so, again, with a kind of deadpan and satirical vacancy that adds to the weight of the vignettes depicted.

“Load down the stairs onto the sidewalk, down about six blocks,” she begins while the drum machine and keyboard lock into a groove underneath her. “I don’t know, man, I’m just a girl,” she continues. “Some goblin says, ‘I don’t know if you’re supposed to be here.’ I show my badge – he rips my head off.”

She returns to a similar setting in the second verse. “Some lady says, ‘I’m not gonna let you back in there.’ I show my badge – she sets me on fire. It’s not that bad,” she continues, before reaching the punch line. “‘Do you want check or wire?’”

In the chorus, as best as she is able, Sprague tries to find some figurative distance from both the monotony described and her growing disdain. “I’m alright,” she begins. “It depends who is asking – who’s asking? I don’t mind. I just think it’s interesting.”

As the song skitters towards its conclusion, Sprague makes one final observation, or rather, a kind of resignation – something that in an idea presented, connects slightly to one of the songs on the second side. “And what’s time – I just blink and I’m somewhere else doing the same thing.”

And maybe there is no need for a resolve to be found as these songs come to their endings – because both “Critical Damage” and “Dead’s in The Van” both end not with unanswered questions exactly, but there is no clear resolution arrived at. Sprague, at least here, is crafting these very meticulous moments. Moments of feeling dejected. Moments of exhaustive minutiae. The moment ends. The moment passes. Everything keeps moving.

* * *

And something that I think about, and it is perhaps because I am chronically online, often scouring music news outlets or social media for the next thing I should find myself interested in,

but something that I think about is the way artists, or performers, have to promote themselves – it seems endless if you not even want to “make it” as a musician, but even for it to be an arguably sustainable decision.

The idea of the traditional cycle is, of course, practically a relic. And because everything moves so quickly now, I am not confident that kind of model works for everyone – but the notion of writing and recording an album, releasing it, touring in support of it, and then even taking just a little bit of time away before it all begins again, is something that a number of newer, or younger, artists, for whatever reason, opt not to do.

In the year that followed the release of Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World, Sprague released a single, the blistering and explosive “Think Nothing,” which at the time, I had presumed would find a home on the soon-to-be-announced full-length. It proved to be a one-off, as another year elapsed before she announced her second LP, and “Think Nothing” was not included in the tracklist.

But this is how it works now, I think. Or what has to occur. To fight for relevancy in what is a certainly overcrowded market. To be remembered when music is something that is seemingly less experienced and enjoyed and returned to and more of a disposable product.

I tell you all of that to tell you this – the rollout to Peak Experience started in March of this year, with the arrival of the unrelenting, rollicking, and dreamy “Fair Field,” and at the time, because of Sprague’s ability to continue fighting for relevancy and recognition, I did not presume it would eventually signal the arrival of a new album.

“Fair Field,” like two of the other singles released ahead of the album’s arrival in full – the punky “As Scared As Can Be,” and the bombastic and slinky “Flat Circle,” are truly Peak Experience’s most exuberant, or enthusiastic sounding, or I would go so far as to say the most fun songs included among the eight. And it does feel weird, though, sometimes, to describe Sprague’s music as “fun,” but it is because of the way she carefully walks that line and creates such a surprising and effective contrast.

Because that is one of the things that is a marvel about Sprague as a songwriter – and one of the more impressive techniques that a songwriter can pull off, and pull off well. Taking something bleak, or dark, or sad, or whatever, and putting in the effort to dress it up, or disguise it enough with an infectious melody or genuinely interesting arranging, so that we, as listeners, do need a moment before the weight of the song does settle in.

Arriving at just a little over two minutes, “Fair Field,” as do many of the songs on Peak Experience, has no time to waste in both setting a tone, and then getting right to work. Beginning with the quick chug of an acoustic guitar, which is then strummed intently with a warbled, dreamy effect applied to it as the song quickly comes to life with a crisp rhythm, a briskly moving bass line, and atmospheric punctuations.

This kind of momentum is sustained until the first verse is finished, and the pacing slows down as it glides into reserved, woozy instrumental break – there is no real chorus to “Fair Field,” and maybe there just simply isn’t time for one, because it does just unfold with a kind of dizzying relentlessness with Sprague’s existential crisis providing the backdrop for further observations and some uncomfortable personal revelations.

Sprague explains her circumstances very plainly in the opening line. “I’m too high at the Fair Field,” she proclaims. “Going fast as fuck on a Ferris wheel. It’s a long way down to the parking lot – there’s a voice in my head, and it never stops.”

The seriousness, or at least the dread, comes creeping in right after this. “We lost time on our long drive, and now I thought too much, and I can’t decide if I’m too turned up in the plot twist,” Sprague sings, with a natural rise and fall to her voice, as she delivers every syllable so it falls into just the right place. “What if we kissed at the free continental breakfast,” she asks, then, trying to find the humor in her circumstances before adding, “Could I face up to the consequences.”

Her internal spiraling continues in the second verse, and as she has demonstrated elsewhere on Peak Experience, “Fair Field” is a song with no resolve in the end, and Sprague is literally just left with her own thoughts to ruminate on.

“I can sit in this chair and think about your face – it’ll probably pass a couple of days, but I won’t ever know if you ever felt the way I did,” she sings somberly.

And that is another theme that Sprague writes into her lyrics – not often, but often enough, for me to find the ways she writes about longing. Sometimes it isn’t subtle – there are a number of songs about love, and romance, and a kind of yearning that occurs, where she’s pretty direct about it on Somebody In Hell Loves You, but here this kind of fluttering, one-sided feeling she describes comes slowly into the song.

“I should probably die of embarrassment,” she admits quietly, before the song careens into its big, musically cathartic conclusion. “You won’t ever feel the way that I do. I think I’m gonna cry.”

I hesitate to refer to Peak Experience as a “transitional” record for Sprague, but is a collection of songs where you can very clearly hear her artistic growth and development taking place – and yes she does wish to push things, as she is able to, in previously unexplored directions, you can hear her connections to the past that she is at least right now uninterested in shedding, specifically in both the straightforward nature of “Fair Field” and in the third single issued off the album, “Flat Circle.”

Arriving after the album’s halfway mark, lyrically “Flat Circle” finds Sprague ruminating on the existential dread that ripples throughout her writing, while also returning to the depiction of an unrequited kind of longing that she alludes to in “Fair Field.” Musically, it soars explosively – opening with an incredibly crunchy and distorted guitar riff, the entire song is built around his balance of tension and release, allowing things to ascend and expand at just the right moment in order to punctuate the seemingly emergent nature of Sprague’s lyrical delivery.

When it isn’t soaring, though, “Flat Circle” tumbles itself into an impressive, slinking groove that then slides effortlessly into a hypnotic moment of restraint before Sprague lets it go.

“Flat Circle” isn’t, like, paced at a breakneck or frenetic speed, but it does move quickly, and in the way it gathers momentum and is always propelling itself forward, even when the arranging is pulled back slightly, there is an urgency to it – something that is emphasized by the nearly breathless way Sprague sings, really working with her delivery so that it does weave itself into the fabric of the song, creating something a song that is remarkable in the way it remains accessible and even infectious in how it is structured, and while walking that line, gives space for thoughtful, rather evocative observations.

“What if this was in the past – what if time’s supposed to be flat,” Sprague asks in the opening line. “If I throw it in a circle, will I ever get it back?”

“I’ve been sleeping, but I’m still tired – you’ve been running around my mind all night,” she continues before making a humbling, self-effacing reflection. “Walking on a thin line, but it’s fine.”

The emergent nature of “Flat Circle” comes out in the moment when the instrumentation underneath Sprague begins churning around, preparing itself to lift off on command, but in how it swirls, it lays the ground for this surprisingly fun, slinky groove to form – the kind that you do wish to move your entire body in time with. Sprague surrenders herself to this rhythmic pattern in how she, with precision, allows her words to tumble out into all the right places.

“Just because I want it doesn’t make it mine,” she admits, in another extremely humbling, and human observation. “I’ve got the feeling you’d look the other way. I can’t say it ‘cause my tongue’s too tied – blink twice if you know what I’m saying.”

And here, again, is this subtle sense of longing that Sprague peppers into her lyricism – the kind of flustered, emotionally heightened state we can find ourselves in, unable to say what we really want to, and just desperately hoping the other person understands somehow. Something she reiterates in an additional portion to this part of the song. “I’m not really trying to make it hard. You don’t have to come, but I’m getting the car. Doesn’t matter if we make it far – blink twice if you know what I’m saying.”

And as it teeters between the more explosive moments, and the places where it works from restraint and allows a little bit of playfulness to come in, there again is no resolve for Sprague in what she depicts on “Flat Circle” – she ends with still just as many existential questions and no answers in sight.

* * *

And something that I find fascinating, and I think is one of the things that keeps me genuinely interested and often excited about contemporary popular music, is the opportunity to watch a relatively new or an emerging artist continue to grow.

A “career” or any kind of longevity is not assured, or promised. And for myriad reasons, a band or an artist can make only one or maybe two albums, and then opt to disappear. So at least for me, and maybe for you as well, it is impressive when you give consideration to someone seeing it as something that can be sustained. But sustainability, for an artist, does not always mean, or include, growth, or development in sound, or scope, or even as an artist.

So it has been exhilarating, and compelling, to see and hear Sprague’s development over the last four years, and what she has chosen to focus on within her songs because, like, the writing was always there, from the very beginning. It is really this push for bigger and sharper or more dense arranging that could catch glimpses of on her second album, and you can really hear coming through on Peak Experience.

And that growth, or development, is what she wants you to understand right away, from the moment the album begins, on the punky, brash, and briskly paced “As Scared As Can Be,” another one of the songs issued ahead of Peak Experience’s arrival.

“As Scared” opens with a very quickly strummed acoustic guitar, but the additional layers, and meticulous production techniques pile on before she’s even sung the first line – there is the little guitar riff that comes at the end of a phrase to punctuate it, or the subtle percussive shaker sound giving everything just a little guidance into an organized rhythm, or the slightly warbled effect that creates a subtle atmospheric current underneath everything as it all converges.

There is Sprague’s voice, too, which at least in this introductory part of the song, is actually played like an instrument, with specific words at the end of lines then being repeated and bent in tone, sliding up and down, resulting in something that is both genuinely interesting and also very whimsical to hear – all before the rest of the band arrives to kick the song into a more exuberant and crunchier gear.

For the two minutes and change it is given, “As Scared As Can Be” takes off and never looks back – frantically careening towards a finish line, and at times, as it propels itself forward, it feels like a collision of sorts, just in terms of the textures that are being contrasted and then mashed together, specifically in the second verse, which skitters with a quickly programmed drum beat, and on top of it is a very dreamy, delicate electric guitar progression. It doesn’t feel out of place, but it is a little disorienting – but I think that’s the point. At least in this song. To just keep running through different soundscapes, like the searing (and memorable) guitar melody that pops up in between the chorus and the verse, or the dizzyingly fast, warm synth tones that oscillate in the bridge. It’s a restless song, musically, and it remains restless until it slams headfirst into the finish line.

Within the top half of the album, there are the aforementioned places where Sprague sardonically references this theme of identity by saying, “I’m just a girl.” This idea is not introduced, exactly, in “As Scared As Can Be,” but there is this very self-effacing nature to how she depicts herself here, especially the further into the song we get.

“I’m a bitch – I’m annoyed and I don’t know when to quit,” Sprague exclaims with a smirk early in the song, before adding. “I always start the argument but I never want the smoke – I can’t finish.”

And there is a kind of frantic nature to the way the song arrives at its chorus – again, like the way it careens through different sounds and textures, the noisy, crunchy, and uneasy nature here is the point. “I’m so small and as scared as can be,” Sprague shouts. “I taste salt – I’m pretty sure that you hate me. I’m so caught up, I can’t fall asleep.”

And it is a bold opening track – one that is honestly hard to keep up with at times because of the unrelenting nature. And even with as emergent as it is, from beginning to end, it is not the most immediate song on the album. But it is a song that, with enough subsequent listens, you do warm up to because of its ramshackle charm.

* * *

Feels good being down bad sometimes.

Across Sprague’s three full-lengths, what I have realized is that yes, of course, I appreciate and enjoy the guitar driven power pop exuberance that she most often leans into, but I think the songs that are the most fascinating to me, or the ones that resonate with me longer, are the songs where she plays against type – the moodier, or slower songs that can adopt a sense of drama or intensity to them. I am thinking of the smoldering centerpiece to Maybe I Will See You, “Quitter,” as well as, again, that album’s stunning titular track.

I am thinking of the glitchy, emo-adjacent swooning of Somebody In Hell Loves You’s closing track, “Sketching Lessons,” which includes a phrase turn that two years later, I still think about regularly – “It’s gonna be alright, kid. If it’s not, we’ll pretend like it is.”

And it is at this point – the point we do always arrive at, however many thousands of words it takes to get there, where I first must ask for permission to break the fourth wall and address you, the reader, directly, and where I feel compelled to discuss the song that I have saved analysis of for last, and why.

Because there is a rhythm to all of this. Perhaps you understand that. Perhaps it is anticipated. The rhythm, however predictable or familiar it ends up feeling, is always working towards something.

I will regularly refer to the song, or songs, that I have saved until the final act as an album’s “finest” moment. And there is, of course, regularly an overlap here. Between “favorite” and “finest.” I would contend that they can be but do not necessarily have to be the same thing. Perhaps you understand that.

An album’s finest moment is one that I believe to be its most genuinely interesting, or compelling, for whatever reason. Maybe it is the most emotional. The most evocative in its lyrics. The most daring or risky in terms of its arrangement or soundscape. And it is often the case that it is the song in which I will catch the most unflattering reflections of myself within.

The penultimate track on Peak Experience, “All Covered in Snow” is the longest song of the eight included on the record, and it is the most genuinely interesting and compelling to me – certainly the most insular in sound, and moodiest in tone, it slowly lurches forward free of percussion, the only guidance or structure offered is the steady strum of the acoustic guitar, underscored by the occasional flutter or surge of atmospherics and the low rumble of bass notes. And given the glitchy production techniques throughout the album, and the overall energy many of Sprague’s songs have, “All Covered in Snow” is the moment when she does play against type, surrendering to a self-aware, emo-inspired earnestness that is remarkable in just how vivid of a portrait it paints.

“All Covered in Snow” walks such a line of tension, and Sprague sustains that for almost the entire song – really only giving into any kind of release when she allows her voice to rise in the final moments, creating a chilling, incredibly human moment that accurately conveys the mix of longing and desperation that she slowly stirs within the lyrics.

Her writing here is both vague and not – I say that because there is, like, a directness to some of the phrases, or a clarity, but what she writes unfolds in these vignettes, or moments, and we are slowly guided through them, which is what makes it so effective and vivid. And it is revealing, in a sense, but it never plays the entire hand.

“I like girls from Rochester, Michigan,” Sprague begins, quietly. “With brown hair and mutual friends. I like you, but you’re back with your ex again,” she continues, dejected. “And I’m out of town until the year ends.”

And what I think, outside of how literate of a portrait this paints with just a few words, is that “All Covered in Snow” works so well because it operates in this space that is so fragile. Certainly aided by how sparse the arranging is, there is this extremely delicate balance in each verse, and Sprague is cautious not to tip it out of her favor, continuing to long for someone that is seemingly just slightly out of reach.

“Feels good being down bad sometimes,” she continues in the second verse, which is one of the more difficult to hear, but truly identifiable, or humbling lyrics on the album. “But I get so sad when you cry. ‘Cause I could be your angel, and you could be mine.”

And in the tension and fragility that Sprague works from here, it does seem that she, at least by the final verse, has inched closer to the object of her longing. Or, if anything, finds a kind of comfort in where she is with this person. “I like when we’re on the phone for seven hours,” she confesses. “I’m outside, all covered in snow. In my mind, you’re a springtime field of flowers. It’s so nice, I don’t ever get cold.”

However, that sense of longing and desire remains as the conclusion without real resolution, but rather, a sense of want, as Sprague repeats and howls the brief, sorrowful chorus. “Maybe someday I could be your angel, fall right into place. Oh, maybe.”

* * *

If you don’t want me, what’s the point.

It is a terribly bleak line. And it could arrive at any point within the confines of a single song, or within the context of an album, as a whole. And in being the very last thing we hear Sydney Sprague utter before Peak Experience comes to an end, I stop short of saying that it leaves us, as listeners, with an uneasy feeling, but there is an uncomfortable shadow that it casts, and we are left standing in it.

That’s the point, though. I think.

To understand that there are uncomfortable or difficult feelings and sometimes we do just have to sit in them. Sometimes we do, despite our best efforts, find ourselves embracing them.

This has been a theme that Sprague has written about throughout her three full-length albums. Or maybe it is the place that she is writing from, rather than about. A place fraught with anxiety and self-deprecation. A place that is plagued with unshakable existential dread.

“I just think the worst,” she sang on the title track to her debut, Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World. “Think about it all the time.”

There is a playful or sardonic kind of nihilism. The joke until it is no longer a joke but part of the joke is how increasingly difficult it is to tell where the line is supposed to be.

We laugh about it now. My best friend, Alyssa, and I. But she more or less bullied me out of my nihilism. Or, at least, being as vocal or as forward about it as I had been for a number of years.

And I mean, I understand why she did it. Because it was certainly one of my least charming or endearing qualities. The joke until it is no longer. But the joke wears thin. The joke was never funny. My well-documented flimsy relationship with mortality – playful and sardonic until it wasn’t.

I just think the worst.

What’s the point.

And it isn’t fun to hear – I get it. Ruminating on how long the planet would last. On how long I was going to last. But it is difficult to remain hopeful. I understand why people wish to, though. It feels like an impossible ask sometimes. To believe that things, both large and small, are going to feel different. Are going to get better. Be less heavy. Not as bleak.

There were the years when things felt the heaviest and the bleakest. And in turning 42 very recently, I am surprised to have made it this far because there was a long time when I was simply uncertain.

A joke until it is no longer.

It is difficult to not even remain hopeful but to find a sense of hope, or optimism, at all, when what you have mostly known, for so long, feels so hopeless.

Peak Experience comes to an end with the jittery, ominous, and noisy “Your Favorite,” where against crunchy drum machine programing and the eventual arrival of a sharp, bashed out rhythm from behind a drum kit, and amidst a number of atmospheric effects and tones, and manipulations of her voice, the song finds Sprague lamenting about the end of a relationship. She’s not bitter, exactly. But rather just exhausted and deflated. And still harboring some anger.

“You were the one, I didn’t lie,” she proclaims in the first verse. “You were the one, I let it die,” she continues, before retreating behind the subtle sense of humor she tries to maintain throughout the album. “Screaming, crying, hissy fit. You can’t fire me – I quit.”

In her deflation, “Your Favorite” does become an exercise in self-deprecation the further along it inches, continuing to shift in its tone. “Guess nobody wants my love. Guess you don’t want me – no one does,” she pouts. “I don’t ask a lot. Just want to be your favorite girl. I know you said ‘Uh huh,’ but I can tell you’re not so sure,” which does recall, and perhaps it is done so intentionally, a lyric from the searing, shuffling single, “Smiley Face,” from Somebody In Hell Loves You,” where she sings, “Baby do you love me now – you hesitated.”

“I can see your point of view. Reading Rainbow context clues,” she deadpans in the final moments. “I don’t think I’m paranoid. If you don’t want me, what’s the point.”

And there is a multitudinous nature in all of us, isn’t there.

For as bleak, or riddled with anxiety as Sprague still is, but certainly on her debut, there was also the incredibly bold, and defiant way that it opened – the enormous, thundering anthem, “I Refuse to Die.”

Maybe I Will See You At The End of The World came out near the top of 2021 – a tumultuous, difficult, uncertain time, still, simply in terms of navigating how our lives had shifted over the course of 2020. But it was an album that found me when I needed it – a difficult time, personally, as I faced, amongst other things, an unanticipated loss and subsequent grief, and a continued slow descent into a deep, dark depression.

And I hadn’t thought about it for a number of years, but at the time, in 2021, when I had immersed myself in Maybe I Will See You and in a sense sought comfort in it, in thinking about the bombast and the audacious nature of the album’s opening track, what I had said was, “I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I have ‘refused’ to die, but maybe, in thinking about it, the act of getting out of bed, going to work, and jus pushing yourself through, even when it seem impossible – especially within the last year – is a small act of refusal against simply giving up.”

I don’t think giving up was ever, truly, an option, but I also never viewed what I was doing as the refusal of death.

The well-documented flimsy relationship with mortality.

The joke until it no longer is.

And there is a multitudinous nature in all of us, isn’t there. I mean, there has to be. We are contradictory. It can be frustrating, or maddening at times. But it is part of the human condition.

We laugh about it, but Alyssa, my best friend, more or less bullied me out of my nihilism. Or, at least, being as vocal or as forward about it as I had been for a number of years. And, I mean, I understand why she did it. It was certainly one of my least charming qualities.

The playful and sardonic kind. The joke until it’s no longer a joke but you see part of the joke is how increasingly difficult it is to tell where the line is supposed to be.

The joke wears thin. The joke was never funny.

I just think the worst. I think about it all the time. What’s the point.

And I mean, I understand why she did it. Alyssa. Why she, over the course of our friendship, continued to point out how she disliked this part of my personality. The penchant for questioning how long the planet would last. On how much longer I was going to last. Because it is difficult to remain hopeful. And what I didn’t get before, but I think I understand a little better now, is why people do want to remain hopeful. To tightly clutch the fraying thread of something good. Something to look forward to. To be optimistic about.

It feels like an impossible ask sometimes. To believe that things, both large and small, are going to feel different. Going to get better. Be less heavy. Not as bleak.

I hadn’t thought about it in awhile. The way Sprague repeats that line in “Sketching Lessons,” at the end of Somebody In Hell Loves You. “It’s gonna be alright, kid. If it’s not, we’ll like it is.” And at the time, it made me think of the expression Joan Didion used at the start of her essay “The White Album.”

“We tell ourselves stories order to live.”

And that’s the thing. The multitudinous nature we contain. The contradictions we are. Things feel bleak. Heavy. The impossible ask. But we want to find the reason to continue. The shred of optimism we are hanging onto with both hands.

We can feel dejected. Deflated. We keep going, despite it all.

To my surprise, I am still here. An act of refusal, I suppose. Or the stories we tell ourselves.

Admittedly, at eight songs, and 20 minutes, Peak Experience is, perhaps, shorter than you may wish for it to be – especially if you are a longtime fan of Sprague’s output. But its length lends itself to its urgency. It is an album that demands not to be restrained – and it does demand your attention. And for the urgency that Sprague and her band have packed into these songs, and the enthusiasm they are bursting with at times, there are moments when it is not as immediate of a listen. There are tunes here that do require some patience, and some time, for, if nothing else, an appreciation for the infectious nature with which they are written to reveal itself more and grow on you.

Sydney Sprague, since releasing her debut full-length in 2021, has been a sharp and bold artist, and Peak Experience is a documentation of an artist continuing to grow sharper and bolder with each step forward.

— —

:: stream/purchase Peak Experience here ::

:: connect with Sydney Sprague here ::

— —

— — — —

Connect to Sydney Sprague on

Facebook, 𝕏, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© courtesy of the artist

Peak Experience

an album by Sydney Sprague

© courtesy of the artist

© courtesy of the artist