An extraordinarily personal record, singer and songwriter Danielle Durack continues to develop her already robust, accessible sound and clever lyricism on ‘Escape Artist,’ the follow-up to 2021’s ‘No Home.’

Stream: ‘Escape Artist’ – Danielle Durack

In the stories that I tell, now, about that period of my life, I call her “Bible Girl.”

That is, of course, not her name, and the Bible itself was not exactly, like, a defining characteristic to her, as a person, when I knew her, and when we were in a romantic relationship, but rather, the punchline to one of the stories that I do find myself, more often than I thought I would be, telling about someone that I was involved with for three years, well over two decades ago.

She was religious — spiritual, whatever you want to call it. I can see that now, and have come to understand that now, as I have aged, and at the time, when I was all of 19, and 20, it was something that I don’t believe I really, truly, fully could comprehend, in terms of what it meant, and how, at times, it could complicate things within our relationship.

I don’t believe I really, truly, fully could comprehend how she was, perhaps, disappointed in, or frustrated by, my lack of interest and, at times, dismissiveness of religion — Catholicism, specifically.

I refer to her as “Bible Girl” because, towards the end, maybe three months before I broke up with her on a Sunday night (a Sunday! The Lord’s Day!), she had suggested that, during a summer we’d be spending away from one another, that we both read the same book, and then discuss it during our phone conversations.

When I asked her which book she wanted to read, she told me she wanted to read The Bible, and without missing a beat, I responded by saying, “Can’t we read a good book?”

This did not directly contribute to the end of our relationship.

Not directly.

And the reason that I am even referencing someone that I was, at one time, in a serious relationship with, is because Bible Girl, at some point, took ownership of a hooded sweatshirt of mine.

It was navy blue, and enormous—an extra large, purchased when I was all of 16 or 17, at a time when I was not at all comfortable or confident with my body, and was still, in some ways, growing into it. On the center of the sweatshirt, in bright yellow screen printing, was an image of a bomb—the kind that would drop from an aircraft, with three stars in the middle of it, and three interconnected circles surrounding it.

Underneath it was the name of the band The Get Up Kids, an emo band from Kansas that I discovered shortly after I turned 16, around the time they released their second album, Something to Write Home About.

And I think that maybe Bible Girl just liked the design on it, or the rich navy blue of the fabric. To my knowledge, I don’t think she had strong feelings about The Get Up Kids, one way or the other. But the sweatshirt became less something of mine and more something of hers during the three years of our relationship—and those things happen, I suppose, the longer you are involved with someone, and spending all if not most of your time around, or with, and more or less staying over every night.

I don’t even remember if it was a sweatshirt that, at any point, became a part of the rotation of things she would wear, even semi-regularly—it is hard to remember, of course. Or if it was just a a sweatshirt that she would occasionally wear to bed, or would live in the cumbersome laundry basket placed in front of the closet door in her dorm room.

When I ended things with Bible Girl, I think, at some point, she asked if I wanted the sweatshirt back, and at the time, I told her no, I didn’t. That she could keep it. And I wonder, and have wondered, off and on, especially within the last few years, if she did keep it. If she still wore it to bed, or if it was crumpled up and tossed into a closet somewhere.

I wonder if she just threw it out, out of anger, or resentment. Or if she took a pair of scissors to it and cut it up into rags.

If it wound up being donated to a Goodwill or someplace similar.

And I think about this now because of how singer and songwriter Danielle Durack opens her new album, Escape Artist – the first few lines of the album’s first single, and opening track, “Shirt Song.”

“Sleeping in my ex’s shirt—I honestly don’t think too much about him no more,” she begins, her voice robust and gentle, coasting gracefully and casually over the muted strums of the acoustic guitar.”Can’t count the ways that it doesn’t even hurt,” she continues. “A couple wash cycles, that sh*t don’t even smell like him anymore—and life goes on.”

Life goes on.

“I Cold Stone ‘Gotta Have It.’”

And the sign of a good songwriter – or, perhaps, an intelligent, or sharp songwriter, is when they pen something that is inherently clever, or something that serves as a little bit of a wink to the listener, and they know not to linger on it too long. Giving it space – just enough space – before moving onto the next line, often creating a kind of double take listening experience, where you have to play the song back, or scour the liner notes, to confirm that you did, in fact, hear it correctly the first time.

Danielle Durack is this kind of songwriter.

It’s a skill you can hear in the way she honestly reflects in her writing throughout Escape Artist, but it’s also a skill that Durack possessed when she released No Home, at the beginning of 2021 – a skill that, within a specific moment on the album, was what made me do that double take when listening, and truly take note of her as a singer and songwriter.

It happens within the shimmering, bombastic, soaring, and infectious “Broken Wings,” which, with a title like that, implies it might be much more of a serious, or a dramatic song than it actually is. In the hands of Durack, it is a self-effacing lamentation of a less-than-stellar boyfriend and the “I Can Fix Him” mentality that she is unable to free herself from.

“You’re a special kind of tragic, so naturally, I’m attracted,” she sings slowly as the song begins. “Don’t know what it is about those broken wings.”

“But I Cold Stone ‘Gotta Have It’ when they’re down and out and ragged,” she muses. “Honey, you can come home with me.”

And there is something, to me, a “lyrics person,” impressive and undeniably clever about finding a way to describe an attraction, albeit a perhaps unfortunate one, though using the metaphor of the largest size ice cream scoop possible offered at a very specific chain—and doing it so subtly. It’s just a little smirk, to the listener, one that barely even registers at first—because she gives it just enough space before pushing the song forward.

Ever insightful and clever, Durack takes her songwriting and her poignant reflections further inward across the nine songs featured on Escape Artist – it isn’t a “dark record,” per se, but it is one that finds her working within comparatively much more robust and daring arrangements for her songs; and lyrically, her writing exists in a self-aware, self-referential, incredibly thoughtful and thought-provoking space where she sifts through the wreckage of when a relationship goes south, and in a stark, fascinating turn, works through sudden grief and loss, and the kind of existential dread that is synonymous with the human condition.

Life goes on.

“A couple wash cycles,” Durack observes, casually, in “Shirt Song,” near the end of its first verse. “That sh*t don’t even smell like him anymore — and life goes on.?

Life does go on. And for as often, specifically within recent years, that I have wondered what became of my Get Up Kids sweatshirt that the girl that I now refer to, in stories, as Bible Girl, took ownership of at some point, early on, during the three years we were in a relationship, the truth is that it is not an article of clothing that, if I had happened to retain it, I would have carried with me for the next two decades.

It, at this point, would be entirely too big – comically oversized on the slender frame that I, over time, grew into. And I wonder what, in between my final year of college, and now, as I enter into my 41st year, would have become of it. Would I have held onto it – keeping it in a box, buried in a closet, or in the basement because I was too sentimental for myriad reasons and could not bear to part with it?

Or would I have donated it in a bag of other clothing that I was no longer wearing?

Or, would someone else have, eventually, taken ownership of it?

Life goes on. And it is the idea of that—that life, does, in fact, go on, regardless of the situations we might find ourselves within, that Durack explores throughout Escape Artist.

Life goes on, whether we want it to or not.

Escape Artist isn’t a “breakup album” exactly, but across its nine songs, Durack does depict, among other things, moments from both the highs, and lows, within the tumult that can often be found within a relationship. And “Shirt Song” isn’t a “breakup song,” exactly, either, but it is a song that places us well within the aftermath, and the complexities that come with that.

The relationship is over; the boyfriend, or partner, is long gone, but the shirt remains. The scent of this person washed away, yes, but the shirt itself, and the memory attached to it remain.

Though life goes on. Whether we want it to or not.

“Shirt Song,” in its structure, as well as lyrically, is the ideal opening track for Escape Artist. It is indicative of what the album sounds like as a whole, certainly, and it does not set the entire tone for the eight songs that’ll follow, but what it does is reveal hints of what’s to come, sonically, and it does, more than anything else, show what makes Durack such a compelling songwriter with a knack for clever lyricism and infectious melodies, of which there are myriad examples throughout the album as a whole.

Durack wastes no time with “Shirt Song,” taking a huge breath in and then exhaling on the first line, which begins immediately, over the top of her contemplative, muted guitar strumming—her voice full, soaring to just the heights it needs to while still maintaining a kind of fragile, or delicate quality, and allowing space for, as she reflects on the need to put her ex’s shirt through the wash a few times to get rid of his scent, a little smirking bitterness as well.

Musically, throughout Escape Artist, there are a number of places where Durack and her assemblage of musicians walk the line between restraint and release—and you can get a feel for that one “Shirt Song” starts coming together, with the steady rhythm tumbling in after the first verse, along with a dreamy, reverby electric guitar that noodles quietly over the top of it all.

And there are moments where Durack, and her band, achieve a kind of cathartic bombast, when the arranging within a song doesn’t get away from them, but they do loosen the grip on what’s holding it back—“Shirt Song” is not one of those songs, though there are implications and hints that it could go to places they do not wish to take it. The music recedes during the gentle, melancholic chorus—“One last call to calm me down,” Durack coos. “One last kiss and one more round. Now hand it off to time and space—oh, it’s doing its cruel magic…feeling better every day,” she continues, while the music swells back up around her, building up, and just a little bit louder or at least a little roomier sounding within the third verse, which is where Durack is the most self-effacing in her reflections.

“Don’t know why I kill myself over details,” she begins. “Always wishing I was somewhere else. But life has shown me I’m stronger than I thought—crueler than I ever want,” Durack observes, and then a few lines later, one of the most poignant in the song, certainly, but also within Escape Artist as a whole—“I’m left thinking maybe I’ve grown. Or, maybe, I just don’t feel anything anymore.”

And it, like the sly reference to a large scoop of ice cream, from Escape Artist’s predecessor, is not lingered on – Durack breathlessly sings that line, pushing her voice, and all of the syllables within the lyric, before the song slides back into the reserve of the chorus.

Lyrically and musically, “Shirt Song” is cyclical—a fascinating songwriting device to watch unfold as she leads us through the small ripples where the song builds up more momentum, before that all effortlessly evaporates, and we’re back to where we started, with Durack, strumming the acoustic guitar, musing about her ex’s shirt, detailing the minutiae of her day—which, if you listen carefully, is something that she references later on within the album.

“Sitting in my ex’s shirt—boiling water, making coffee, folding laundry, writing verse,” she lists off. “It all just feels a little too absurd,” Durack continues, this time, being a little more honest about the shirt, and her feelings that remain about the former partner she still associates with it. “We fell in love. A couple months. And now you’re nothing but another shirt.”

And life goes on.

Whether we want it to or not.

Later, in both the subsequent track, the charmingly titled “Ice Caps (Live Laugh Love),” and within the album’s second half on “The Door,” Durack, after spending time within the ruminative space that comes after the end of a relationship, she takes both forward, and back—back to when things were good, or just beginning, and even though there was uncertainty, there was still hope, and forward to the moment when someone knows that they need to leave.

And the appearance of one of the more cloying expressions in recent memory, “Live, Laugh, Love,” appearing parenthetically in the title of “Ice Caps,” it is done in a biting, sardonic way, and in its usage within the song, Durack takes it an unexpected but extremely welcome place when she sings in the song’s chorus, “And so it goes—you life, you laugh, you love, you die alone.”

Durack, both lyrically and within the song’s arranging, puts in a place of nervy tension—the percussion clatters and pulsates rhythmically, and there is, from the moment it starts, in the hush of the acoustic guitar string plucks, and urgency, or immediacy, that is only magnified once the rest of the elements of “Ice Caps” arrive, like a thick, rattling bass line, stirring, emotional stabs of piano keys, and layers of atmosphere that swirl around in-between and underneath everything else.

It isn’t ominous, exactly, but there is something unnerving that oscillates through the song, which mirrors the anxieties that Durack sings about—creating a stark contrast because her voice is honestly quite soothing at times, and often layered in a way that makes it very lush and beautiful, then it is drifting across the top of the churning of something a little dark, and a little pensive or inward in sound.

“Ice Caps” depicts a happier time in a relationship for Durack—near the beginning of something new when there the collision of excitement and uncertainty. “You say you really see me, and I don’t know what you mean,” she confesses in the moments that lead up to the chorus. “But it sure sounds lovely, and I like when you’re looking at me.”

“You told me you love me, and I believed,” she continues in the moments before the surging of the instruments swells and bursts in the chorus. “Nothing’s ever been quite this easy—god, it’s really something.”

And for as much hope, and slivers of optimism as Durack is able to muster in “Ice Caps,” it is a song that ultimately descends into an anxious spiral—“I don’t know when I got so scared of flying,” she begins, near the end of the song. “And started holding my breath. Never used to be so scared of trying. Been singing everything os quiet—I don’t know when it got hard to listen. Thoughts racing in an empty head,” she continues as a lead up to the final solemn lines of the song. “I don’t know how it’s gonna end, but I got a feeling.”

If “Ice Caps,” even in its anxieties, tracks the beginning stages of a relationship, Durack arrives at the moment right before it needs to end, and a change needs to be made, on the smoldering, twangy “The Door,” found within the final third of Escape Artist.

Structured around a steady rhythm from extremely crisp sounding percussive, and a mournful slide guitar that adds punctuation to the gentle, plaintive strums of the acoustic guitar, lyrically, “The Door” is remarkably vivid in what it depicts, in terms of the difficult end of something, but in its depiction, what is perhaps the most fascinating is how Durack plays with the point of view within the narrative.

There is a sort of kindness to the first verse of “The Door,” through the grace that is shown by the narrator to the protagonist—again, the song continues to shift, but within that kindness, there is an exasperation, that does quickly recede further and further away with each subsequent verse, and replaced with a visceral desperation, then regret, and then a sorrow.

“Tender-hearted darlin—keep your head above the water,” Durack begins quietly. “Keep swimming ’til you reach that shore. Pretty little mama—give it everything you got and keep fighting ’til you can’t no more.”

“Critical and cautions—think I’m running out of options,” she continues, moving into the second verse, with the song’s instrumentation smoldering underneath. “Might be time to pack my boxes and go.” And it is here, also, where Durack makes the shift within the narrative from a third person, to a first person, and it is also here where the lyrics become less hopeful, and much more bleak.

“Silly little dreamer. Almost made me a believer—been awhile since I’ve seen her now.”

Musically, “The Door” rises and swells, with layers of a sweeping string accompaniment and piano chords coming in as she reaches her reflections at the end. “It was everything I wanted. Oh I had it all, and lost it. It was right there in my pocket,” Durack explains, though quickly becoming self-effacing. “Had to see what else was out there—now I’m grasping at straws for any single sense of purpose. Laying face up on the carpet, landed right back where I started.”

“The Door” is not Escape Artist’s final track, but it is sequenced further enough into the album’s running that it does allow Durack to become self-referential, and she is able to do so with an intelligence and grace, creating an intentional callback to lyrics from “Shirt Song,” but because how emotionally heavy “The Door” is, comparatively, the callback is done in earnest, and without so much as a wink to the listener.

“I’m spending time alone, but it’s really not a problem,” Durack howls in the song’s crescendo. “Doing fine here on my own—finding ways to pass the time. Spending mornings drinking coffee, writing songs about nothing, screaming into the oblivion.”

And even with how stark of a portrait that is painted, and harrowingly delivered in “The Door,” there is the tiniest glimmer of something positive within the chorus, where Durack references the titular door. “I’m there waiting, right outside the door,” she says—the implication that, in your lowest point, you can find yourself again on the other side of it, but the steps you need to take to get there often seem impossible.

The rollout to Escape Artist began towards the end of 2023 – with the album’s announcement, accompanied by the release of the first single, “Shirt Song,” which, of any of the album’s nine songs, is perhaps the most indicative of Durack’s sound, overall. Accessible, firmly rooted in pop sensibilities, a knack for thoughtful lyricism, and a sound that is somewhere in the space between Top 40 and a coffee shop.

There’s a sensitivity, certainly, but there’s also an edge—which, at times, can be incredibly sharp.

The second single issued ahead of the album’s arrival in full, released a few days after the new year, is also Escape Artist’s first turn into a more hushed, insular sound. Slow, somber, and ultimately bittersweet, “Good Dog,” sequence third, is quite the juxtaposition in tone, both sonically and lyrically, from the songs that precede, but it is that juxtaposition, and the deliberately slow pacing, and the palpable sense of sorrow and heartbreak that surge throughout it that make it one of the album’s most fascinating and beautiful.

Beginning with a low synth ripple—a sound that is similar to the undercurrents that you can hear in Durack’s excellent, one-off cover of Abba’s “Dancing Queen” from a few years ago, “Good Dog,” like the tempo itself, is intentionally slow to pull all of its elements together. There is a steady percussive clatter that cements the rhythm, as mournful, restrained piano chords create the melody that Durack’s delicate voice gently float above.

And it does sell the album short, as a whole, to call Escape Artist a “breakup album,” because we do not always meet Durack within the moment that the relationship has ended. And like “The Door,” “Good Dog” is an extremely self-deprecating snapshot taken from another difficult moment within a relationship—on the cusp of a demise, with Durack as the narrator, questioning her worth, both within the context of the relationship, as well as how she may fare on her own.

“I have been waiting by the window in the dark,” she begins with her voice low and fragile. “Keeping quiet—sat listening for your car. A quiet panic that you’re never coming home. Don’t like how you make me,” she continues. “But I know it’s not your fault.”

Durack, within her songwriting, gets just about as much mileage as she tastefully can within the metaphor she uses for the kind of loyal companionship of a literal canine that is woven into the depiction of the relationship in the narrative. “Am I better off alone?,” she asks pointedly and exasperatedly in the first line of the chorus. “Give you up, and crawl back home instead of waiting at your door like a good dog that you don’t want.”

She perhaps extends the metaphor to its absolute limit in the song’s bridge, which she sings with enough somber conviction so that it lands, and works, because in the hands of a less confident songwriter and performer, might be a lot less successful. “And I know you think I’m some designer breed, but I’m just as rescue you’d find on the street,” Durack explains, with a voice full of sorrow. “I’ve been stretching at the door and making myself bleed, ‘cause everybody leaves.”

Durack, then, on the cusp of that demise, wrestles with what to do, and what comes with the decision—to preemptively leave, as she puts it, “Better to call it if I know it’s gonna go. Don’t want you to hate me when I get to be too much,” she concedes in the second verse, and is a sentiment she expands upon near the end in an altered version of the chorus—“Get on the phone and all my mom, let her tell me I f***ed up. That I was wrong,” or, to remain, and try her best to move through, or process the intrusive thoughts that keep her on the verge of self-sabotage.

“What I want’s a change of heart—be strong enough to bear it all,” she sings in the final moments of the song. “Not be so tortured by my thoughts about what can happen while you’re gone. What I want is you back home, wrapped in my arms, that’s what I want.”

And, like “The Door,” in her writing, Durack brings you right up to the point where there could be a resolution, or a clear ending within the narrative—but she does leave us right at that moment, where there are no easy answers, and no clear conclusions revealed for these personal stories that she’s sharing. And, like the often infectious nature of these songs within their melody and structure, the emotional heft and ambiguous endings remain with you long after Escape Artist has come to an end.

And it is hinted at, slightly, earlier in the album, when “Ice Caps” ascends to a bit of a controlled height, or release of tension if you will, but Durack does really let go in a surprising way as Escape Artist continues, with the downcast and surprisingly explosive “Worms.”

And what I have found, the more I have sat with Escape Artist, is that certainly, from beginning to end, it is a great record, and shows the continued growth and confidence that Durack has within her crafts, but there are specific moments where a song, from literally the moment it starts—you can hear something genuinely interesting happening.

Like, you know it’s going to be impressive, or special, or more surprising than the others. “The Door” and “Good Dog” were like that, certainly because of the emotional weight of their lyrics, and “Worms,” which closes out the album’s first side, is another one of those moments.

There is a dissonance, right away, in the sound of the guitar—a kind of sneer that only grows more confrontational and ferocious the further into the song we’re pulled. The chorus to “Worms” is wordless cooing, and it’s within the first round of that the song starts to build with the low rumble and shuffle of percussive elements and the cavernous plunking of ominous piano keys. The real moment of catharsis, and bombast comes with roughly a minute left, when the song detonates in a cacophonic peak—the guitars, crunchier and louder; the drums, pummeling; and Durack’s voice now soaring and absolutely howling over the noise.

It’s a kind of effective and surprising darker aesthetic that, placed where it is within the album’s running, really makes you take notice of it.

Durack, as a lyricist, is often very direct, which is one of the things that does make her such an accessible artist. But within “Worms,” another element that does make it such a standout on the album, outside of the visceral ferocity that it builds itself up to, is the kind of ambiguous, fragmented narrative strung through the verses.

“I think this might be my exit,” she begins quietly, through almost gritted teeth. “I think I’ve had enough. You know you lost me there—I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I clipped your piece from the paper—hung it on my wall,” she connotes. “Still don’t know what it means to me, if anything at all.”

The imagery, as vague as it is, does grow bleaker with each verse, with a sense of something borderline menacing just underneath. “Opened up your can and let out all these worms,” Durack reflects by verse three. “Heard you’re moving on while I’m still sifting through the dirt.”

“Worms” is another song within the album that, by the time it reaches its ending, there is an end to the song, per se, but there is no conclusion within the narrative, or resolution between Durack and the off-stage antagonist, save for a sardonic, biting final line that occurs moments before the climax. “Maybe there’s a time for us in another place,” she muses. “Maybe on a some grassy hillside or swallowed up in space.”

I just want you to know who I am.

And if you will humor me, and allow me, I would, as I often do, and often around this point when I am writing about an album, break the fourth wall, becoming a little self-aware, and addressing you, the reader, directly.

In 2021, Danielle Durack was a guest on the podcast that I launched in 2019—The Anhedonic Headphones Podcast. Regardless of who the guests have been—my spouse, former co-workers, friends, writers, musicians, et al.—what I ask is that they pick up to 10 songs that they are comfortable discussing at length. Songs that they have a memory attached to, or a story they are willing to share, or that it is representative of a specific time in their life.

Among the songs Durack picked to discuss was “Iris,” the 1998 single from The Goo Goo Dolls, originally written for the film City of Angels, then later included on their full-length, Dizzy Up The Girl.

It isn’t a pre-requisite of being a guest on to share something deeply personal, or perhaps difficult to talk about, but the more interviews I did, and the more I learned about how music stays with people, and has affected them, throughout their lives, people do end up divulging personal or difficult things, often about losses they’ve experienced.

I just want you to know who I am

Durack selected “Iris” as one of the songs she wished to speak on because of the connection it had to Dean, who, for a number of years, was her stepfather.

“From my perspective, he was the love of her life,” Durack said during our conversation, adding that Dean struggled with both mental health issues as well as substance use disorder, which did lead to her mother separating from Dean eventually.

“We remained a part of each other’s lives,” she continued. “He was good to me and my brother, and I saw him as another father.”

I recorded the interview with Durack in the late summer of 2021, and during this part of the conversation, she said that while the song “Iris” had been on the list of songs she had sent me well in advance, Dean had died by suicide a week earlier, and she said that “Iris” was a song that reminded her mother of him.

At the end of the song, the line—arguably one of the more poignant and iconic lines from the chorus—is repeated to a point where there is an implied desperation. “I just want you to know who I am.” And it is this line that Durack specifically referenced in our conversation. “Now relating it to this man who was in my life, and his struggles with addiction, and wanting things to be real, and not being able to cope with the harsh reality of life, and this game we all play.”

I just want you to know who I am.

And I tell you all of that to tell you this – Escape Artist’s penultimate track, and truly the album’s finest, most gorgeous, and devastating moment, is called “Dean.”

I have spent over a decade trying to find articulate, thoughtful, and honest ways to write about grief and loss and the way those things affect us, and I can assure you that it is not easy. And I am sure that, for Durack, it was not easy. But even with as difficult as it might be to revisit loss, and grief, and try to find the place where those things can intersect with a kind of joy, or fond remembrance, she does it here with a remarkable tact and grace, creating something absolutely stunning and moving in the process.

And for as surprising of an inward turn as a song like “Good Dog” was to be issued as a single ahead of Escape Artist’s release date, it is equally, if not more, of a surprising turn – bold, actually, the more I think about it, to also share “Dean” ahead of the rest of this record.

Durack explained in a lengthy post on Instagram about the development of the song – that, roughly a month after Dean’s passing, she had a dream about him, where she said that he was, “The healthiest, happiest, and warmest I had ever seen him. I got to hug him, and thank him, and see him one more time.”

“I woke up,” she continued. “Cried, talked it over with a friend, cried some more, and wrote this song.”

Structurally, Durack knows precisely what she’s doing, and knows how to tug at your emotions, in how “Dean” begins with a slow, deliberate simmer, before she conjures it up into something much lager, and much more powerful. Opening with the delicate strums of the guitar, and the low ripple of atmospherics cascading in underneath her, which usher in the steady, punchy percussion, and somber piano chords ringing out.

“Dean,” like other songs on Escape Artist, doesn’t exactly return to a chorus, but rather, the verses just continue to unfold with more urgency, pushing Durack’s narrative of joy and grief forward, and with that in mind, the song’s arranging, with ease, continues to grow to a point where it does take off – not as viscerally as it does in a song like “Worms,” certainly, but rather it soars just high enough, and there is enough tension released to create a beautiful, terrible, noisy moment that is representative of the power within that collision of joy and grief, and the space that exists where those two things meet.

“I had a dream I was flying,” Durack begins in a hush, over the contemplative sounds of her guitar strings. “Mother said you were alive again – more alive than you’d ever been. I sprinted out to the water’s edge.”

I have spent over a decade trying to find articulate, thoughtful, and honest ways to write about grief and loss and the way those things affect us, and I can assure you that it is not easy. And, a number of years ago, I had been assured by someone that there was, in fact, a space where grief and joy could co-exist, and I had, for a number of years, been looking for that space – I never found it. Not really. And it was less than a year ago when I realized that, much to my surprise, I had stopped looking.

The thing about grief is that it can, at least for me, and perhaps for you, too, make you feel a lot of misplaced regret – the things you should have done. The things you could have done differently. What you should have said but didn’t. You blame yourself. For something that you had no control over. And it is this part of grief that does make it an awful, and lonely place to find yourself in.

And there is hope, yes, and surprise, within the writing of “Dean”’s first verse, but it isn’t too long before Durack pulls us into that place of regret that always lingers in the face of loss. “You didn’t say you were leaving, but looking back, I guess you did,” she confesses. “And god, I wish I had heard you then – guess I wasn’t listening.”

As the song builds up to the moment of emotional release, Durack, in her words, refuses to hold back – there is an unabashed earnestness that is admirable and necessary as she continues to find that space, for herself, where joy and grief are able to co-exist, and the hope that there is something better for someone once they shed this mortal coil. “I hope that little lake house wasn’t only in my dreams,” Durack exclaims. “I hope where you are is kinder than this earth could ever be. I hope when you took that final leap of faith, it felt like flying.”

Around ten years ago, I was not doing well, and that was, at least in part, because I was finding it extremely challenging to process grief that I had been carrying around, uncertain what to do with it. Out of desperation, I found myself trying out an, at the time, somewhat unconventional method of therapy called E.M.D.R. And in doing it, the thing that I was supposed to take away, or use as a means of talking myself out of the grief, and everything that came with it, was to remind myself that who I was grieving the loss of was loved.

That they knew they were loved. And that the love was allegedly enough.

And I tell you all of that to tell you this.

“Dean,” between its third and final verse, reaches its absolute peak, as Durack ruminates on this very notion – the notion of love and where that falls within grief. “I hope somehow you finally know how much we really love you,” she pleads. “And that any doubt about it is left in this world behind you.”

That emotional build then recedes and leaves Durack, and the strums of the acoustic guitar, as the final thing we hear – her voice, much more fragile than anywhere else in the song, quietly singing the final lines, where her experience, within the dream, offsets a little bit of the pain that comes with unexpected and sudden loss.

“I got to look in your eyes again. I got to say goodbye.”

Life goes on. Whether we want it to or not.

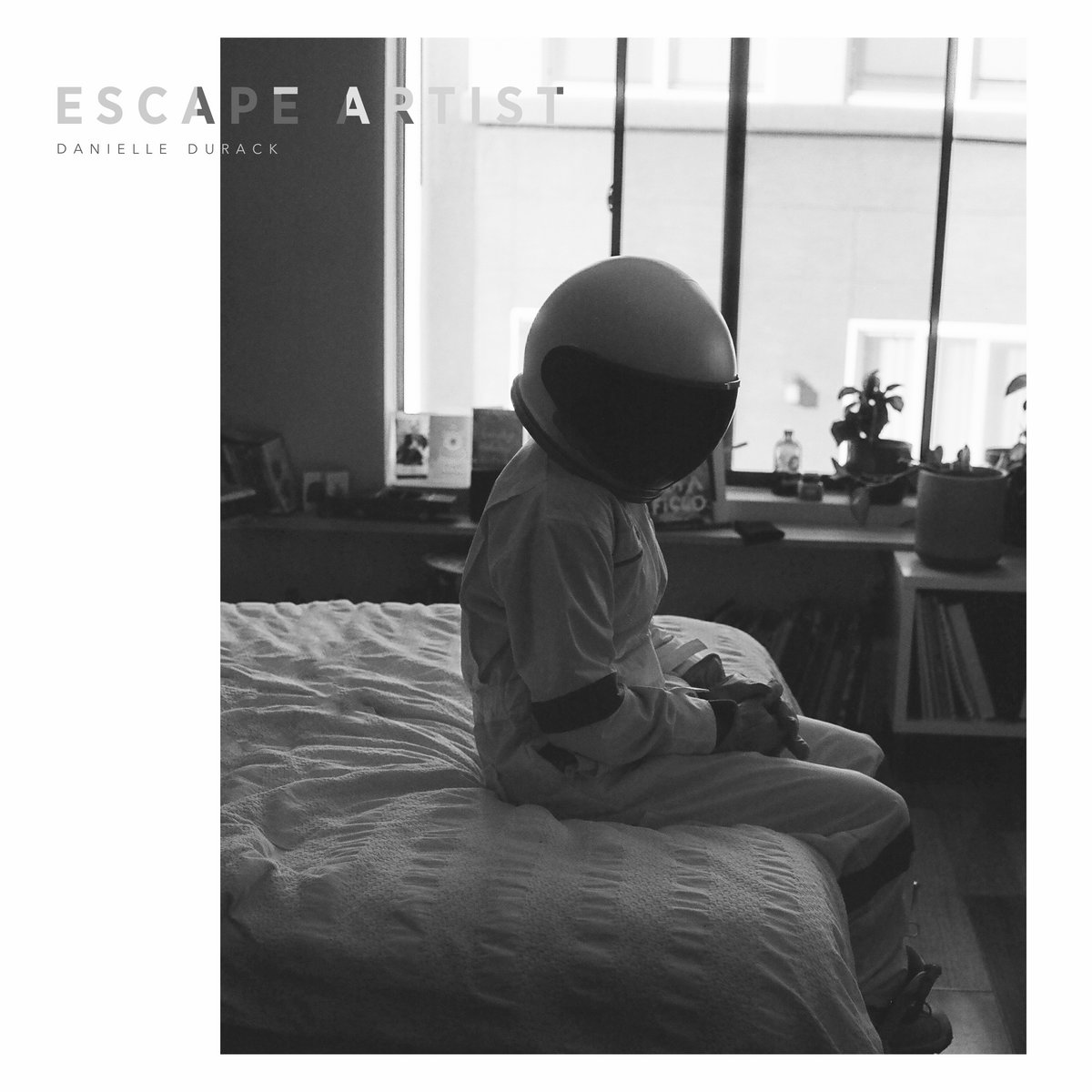

Escape Artist concludes with what Durack herself, in an AMA on Instagram recently, described as a kitschy song, and also the song that served as an inspiration for both the title of the album itself, and the astronaut aesthetic found on the cover photo and within the liner notes – “Moon Song,” which, arriving after the emotional devastation of “Dean,” is a small reprieve, tonally, and a bit of an epilogue.

There is a playful nature to “Moon Song” – one that isn’t missing from the rest of the album, but one that Durack had kind of left behind following “Shirt Song,” in terms of the knowing winks to the listener, and the slightly lighter feeling. Even in its lighter feeling, though, and the gossamer nature of the arranging, there is a seriousness, or a kind of sadness and exhaustion, found within her musings on the very notion of being able to depart the planet, simply as a means of escape.

“Living on Earth keeps breaking my heart,” she sings in the second verse. “Testing my patience and giving me scars. And all that I want is to lay in your arms. Send me away – it’s all so f***ing hard.”

There is humor of course, sprinkled throughout, about living on ramen noodles and the inevitability of missing her family, but the conceit of the song is cleverly, and subtly, tied back to something from within the album’s first track. “Living on Earth keeps breaking my heart,” Durack sings in the final verse. “But it always heals, and life goes on. The world’s still turning, so there’s always tomorrow. I hold onto hope, ‘cause it’s all that I got.”

And there is always tomorrow. Which is something, as of late, I have found myself saying, when one day is coming to an end—a day that, perhaps, did not go as well as I would have liked it to. Or, if I did not get as much accomplished with something creative as I had intended. I find, as I sit on the couch, in a state of spiraling, more and more I say, “there is always tomorrow.”

Maybe tomorrow will be a more reasonable, if not better, day.

Life goes on.

And I find that, for a while now, holding onto hope is extraordinarily difficult. Maybe it is for you as well. That it seems like there is so little that gives one hope, and what we do find—small slivers of something good in our lives, we really have to hold onto those things tightly and appreciate them because they are, at least for me, the things that keep me upright.

Life goes on. Whether we want it to or not. And from beginning to end, on Escape Artist, Danielle Durack examines, with grace and, humor and honesty, the human condition.

Life goes on. And there are moments where that is not necessarily the worst thing.

— —

:: stream/purchase Escape Artist here ::

:: connect with Danielle Durack here ::

— — — —

Connect to Danielle Durack on

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram

Discover new music on Atwood Magazine

© courtesy of the artist

:: Stream Danielle Durack ::

© courtesy of the artist

© courtesy of the artist